Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Milos Forman's _Valmont_: an anti-Thatcherite era costume drama · 6 March 09

Dear friends,

As part of my project on Clarissa 1991 (Robert Bierman, director, screenplay by David Nokes and Janet Barron), I’ve been watching relevant film adaptations. They’ve included Nokes and Barron’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Harriet O’Carroll’s Aristocrats, Jacques Rivette’s La Religieuse, Stephen Frears’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses (see earlier blogs or google “site:moody.cx the title”). Well, this week I watched Milos Forman’s 1989 Valmont (screenplay Jean-Claude Carriere, producer Michael Haussan) attentively.

I enjoyed it very much, but was not at all surprized to find that almost uniformly it received negative reviews from the official press (now found on the Net) when first released. Unluckily it came out the same year as an apparently faithful adaptation by Stephen Frears’ and Christopher Hampton, Dangerous Liaisons. Frears and Hampton’s film also boasted a large number of box office stars; 1989 was before the 1995 BBC/A&E P&P and Colin Firth was as yet an up and coming actor, not arrived. The result is that it’s difficult to find new and must be bought used. Yet Valmont is in a DVD format, and I’ve found half-apologetic blogs and comments on it, where the viewer enjoyed and appreciated it, and not just out of an attraction to Colin Firth. I’ve even found one scholarly article defending the film, and am awaiting it in eager anticipation.

Of course the problem is that, like Rozema’s and Wadey’s two different Mansfield Parks and “my own” Clarissa 1991 among other condemned interesting film adaptations, Valmont is a commentary adaptation, signalled to us strongly by the change in title. No matter. The unexamined Pavlovian reaction of comparing it literally to the events and characters of LaClos’s book turns up many changes, and make it easy for critics to parse these changes as robbing the film (and by extension) book of depth. It’s so tiresome to find intelligent people persisting in this literal alignment. They miss out.

So, here is a film analysis which argues that Forman’s Valmont is an intelligent interpretation of LaClos’s book that in some ways reflects LaClos’s book more humanely and sensibly (and just as deeply to use the honorific word) than Frears’s.

First, Valmont. The major change in the film is to make Valmont (played by Colin Firth very well) a victim hero. This is not simplistically done since he is a rake, careless, amoral, sexually promiscuous, a casual liar when it suits him, idle, playing Madame de Merteuil’s (Annette Benning) dangerous games in order to go to bed with her, which he doesn’t get to do in this film as he’s outwitted by her (as he is in LaClos’s book). Nonetheless, despite his manifest faults, Valmont is presented as a believable human given the world and order he lives in, with some decent impulses and a gentle kind heart (Firth is good at this).

He is outflanked and destroyed not just by Merteuil, but importantly (and another change from the book), the complicity of the other women in the story, a genuinely young Cecile (Fairuka Balk), Cecile’s mother (Sian Philips) and Madame de Tourville (Meg Tilly) who all desert him for the older men they have been sold to because they know their bread is thoroughly buttered by marrying for money anyone who has a great deal of it and then living a life of lies and strategems. This is the lesson Cecile learns in the film, and it’s one Tourville knows before it starts. Thus Tourville is a reluctant lover partly because she fears for her emotional life, but also because she fears for her security, standing, social as well as emotional safety and peace. When Valmont is killed in an absurdist duel (he is drunk, brings along peasants, and it’s made clear that Danceny (Henry Thomas) is himself just as corrupt, a creature of appetites as he’s been bedding Merteuil, he is not punished providentially (as in the book) but by through the luck of the game.

The final scene anticipates a near closing shot in Clarissa 1991 when it’s last shot in focuses on the coffin of the hero:

The great house for which everyone pays a real price is seen

The way protest literature works since the 19th century (Uncle Tom’s Cabin is classic here) is to have a victim at the center which makes visible what are the real values of the people around said victim. The victim need not be a saint at all; as James Baldwin argued, intelligent protest literature does not give the victim clean hands either, makes him another of us. We’ve just seen Cecile’s posh wedding, and then Madame de Tourville mourn briefly and decorously over the coffin but then ride away with her old man in a luxurious carriage:

Tilly maintains an intelligent expression on her face throughout

LaClos and Frears’s Tourville dies of heartbreak. Forman’s film is not sentimental. We see Forman’s Danceny flirting like a rake with yet more women. The only face beyond Tourville’s to register a more permanent sense of grief for his death is Merteuil’s (Annette Benning) and we are not sure what for, as she is watching Cecile’s wedding. Loneliness? More, she has lost a playmate.

This is an ambiguous anti-ancien regime film which does make the life style seems so sweet (unlike Frears’s film), so alluring for the filthy rich (as Talleyrand said). Fabia Drake plays Madame de Rosemonde and she conveys how her life has been one luxury after another as long as she knew when and what to be silent about, where to take her pleasures and her luck held. We don’t know her history but have no reasson not to believe she didn’t take the path we watch Cecile take at the end. Frears’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses has the characters as repulsive, imprisoned, not enjoying themselves in any sensual way, only from a seething kind of triumph, angry glee, and wild neurotic crazed behavior (how John Malkovich tried to make sense of the script he was given and the character who is often today discussed as sick).

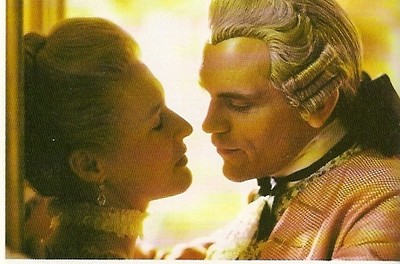

At the opening and now and again, the feel of the film is a light frothy comedy. I surmize Forman had in mind the much-praised 1963 Tony Richardson Tom Jones (with Albert Finney and Suzannah York) for some of the sequences, only the point here is amorality and meaninglessness because of the story’s (from LaClos) contextualization of the romp and dancing. There are dancing sequences, pastoral scenes, here is one of Valmont coming up on the water to a waiting Tourville; she has retired to the country (Madame de Rosemonde’s house) and awaits him:

He falls in the water, no more necessarily adept than Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones. He does not coerce-rape-threaten Cecile in the way Frears’s Valmont actually does; rather he coaxes her into anal sex as she’s writing. We haven’t the scene of a man writing on the naked back of a compliant woman as in LaClos and Frears’s; instead what’s suggested is sensual enjoyment on his and her part of buggery. Richardson’s Tom salivated over Molly as if she were roast beef and the camera lingered lovingly over a woman’s breasts pushed up by one of those very tight bras. As a woman, I feel three is really little to chose here; Ozone, misogynist as he sometimes is, does show in his Cinq fois deux that anal sex hurts women and is understanably not liked by them, is a kind of punishment-revenge (this kind of scene and inference turns up in Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (see my blog on Persuasion for the film as a composite adaptation) in a scene between Renee Zellweger and Hugh Grant, who can do the mean man very well.) This Valmont also has a comic servant who functions as a reality check at times.

It is pretty: like Paul Webber and Olivia Hetreed’s Girl with the Pearl Earring (out of Tracey Chevalier’s romance novel, also starring Colin Firth as hero) the shots are construed in terms of paintings, here rococo erotic. Madame de Tourville is not on the edge of sexual disaster from the moment she sees Valmont (as in Frears’ Michelle Pfeiffer):

Looking easily unnerved from the outset

but indeed virtuous and keeping her distance form him, uncomfortable, a sort of standoffish frightened woman (of pleasure) I suppose is the idea. Benning as Madame de Merteuil takes revenge the way some drink champagne. They really do like physical pleasure which is not the way the story is played usually. In Clarissa 1991 Nokes and Barron has their Clary say “Mr Lovelace does not know how to love,” and we see he doesn’t.

Annette Benning plays Madame de Merteuil the way competent actors play Iago from Shakespeare’s Othello. On the surface she is sweetness itself and never drops the mask. She can cry on cue too. As with Frears’s and LaClos’s text/films, you could call this an anti-feminist film. Glenn Close who has a long career of playing singularly savage cruel mother and sexualized figures is he powerhouse of Frears’s film and there are countless shots emphasizing how Valmont is her boytoy, what she (like Richardson’s Lovelace) manipulates.

Close’s Merteuil needles Cecile ( and lures her into corruption—which actually breaks probability (though this is not important as most films repeatedly break probability).

There is, though, no moment where this is made explicitly understandable, for the famous letter 81 where LaClos’s woman explains her hatred of men and society is completely omitted. It’s included in Benning’s speech where she does not attributes her behavior to a desire for revenge on men (LaClos’s take), but rather wants something narrower, a result of her experience: she wants never to marry again because she wants never again to be coerced into sex (when she eludes Valmont after he says he has made good their deal) that’s what she says.

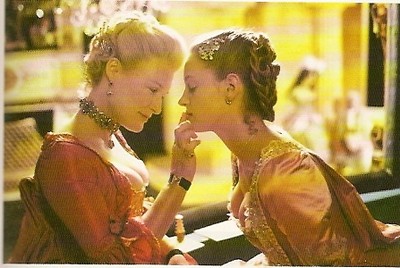

She will be in control of her body. It’s clear when sex happens she’s in charge—as in her tryst with Danceny.

As in the LaClos’s book and Frears’s film, Forman and Carriere’s other women are not manipulators. They are implict upholders of a male hegemonic order which at once suffocates, gives them power when they are old, and safety and physical comfort (during the day at least) when young. Madame de Volanges (Sian Phillips) loves to have her daughter under her thumb and is made very unlikable. I’d say Frears is not interested in critiquing the ancien regime. Yes there is a scene of poor people and Malkovich as Valmont acting out helping them to impress Tourville (presented as easily duped) but these poor are made into exemplars of pietry, while the poor in Forman’s film are presented more realistically, drinking and snatching pleasure where they can too. Frears’s film (as has been pointed out) comes out of Freudian theories of where promiscuity comes from, and instead of daylight social criticism, we are lost in a psychological romance-dream.

Arthur Miller remarked that the displacement of social criticism by psychoanalysis has vitiated the power & any real relevance of much contemporary American drama. Perhaps this is too strong. I appreciated Frears’s film. Like LaClos’s people, Close and Malkovich are damned souls; if they haven’t understood the first thing that makes living worth while is really to care about another, and instead are psychologically destructive, one could say LaClos shows the whole of upper class society (seen in the parents) was just as ruthless and perverse. Frears’s is calling upon the psychological typing Malkovich often carries: in a gothic horror film Mary Reilly (also by Frears and Hampton), Close was a spectucularly ghastly madame in a brothel paired with Malkovich as a high parody of deep evil, he makes jokes as he murders brutally and viciously (including murdering Close’s character). In Frears’s Cecile (like LaClos) is a dope; Danceny (Keanu Reeves) is driven by furious rage from his insulted macho male code. Frears’s film is the much more misogynous as it’s much closer to the book.

In Forman’s film Danceny (Henry Thomas) and Cecile are played by actors who are so young they become innocent teenagers—which may be in line with the book, but is done here to make them part of this ongoing amoral world—a reflection I think meant to recall our own.

Danceny at the duel: shocked and grave at Valmont’s drunken insouciance and mockery, he offers not to duel

In the novel both Cecile and Danceny are so appalled by their involvement in the schemes of Valmont and Merteuil that they do everything possible to morally redeem themselves. At the close of Forman’s film, Cecile is carrying Valmont’s child while marrying Gercourt, so we are seeing the younger generation repeat what has happened before. Like Fortinbras replacing Hamlet.

Obedient to the end of the film, Cecile early on takes dictation

In all three versions, LaClos, Frears’s and Forman’s there is no disruption of the immoral practices of the older generation, and society seems poised to repeat itself once again. A commentary film is also supposed to be somewhat faithful, and Forman’s is that. He was presumably attracted to the book’s capability and relevance to our society as he saw it in the 1980s. It thus belongs to the many films of the 1980s which commented on what has come to be called the Thatcherite-Reagon era (see Lester Friedman’s film study, Fires were Started).

Madame de Volanges as this film’s big winner, imperturbable, dense, never disturbed (Sian Philips played the fatal powerful wife in I, Claudius)

I’ve been reading Sue Harper’s excellent Picturing the Past, a history of costume drama. She shows that from their inception such films dealt centrally with issues of class and showed women having sexual pleasure. The takes on this varied, mostly conservative. As Higson shows English Heritage, English Cinema, she too shows the films intended to reach a wider audience, to be more popular and in the moviehouses mostly, are often commentary types. The very departing from the original text seems to relax the audience, but it is also intended to make the film more contemporary.

What a shame this delightful and yet perceptive presentation of the amorality of society has been sidelined, swiped out by stubbornly unexamined assumptions, which finally come out of the low prestige of films & (in some cases) enjoyment of debunking. I get so frustrated when I read these popular and occasionally scholarly continual prescriptive comparisons of books and films. It’s fetishing too as often the book has its flaws. Certainly at the time of the publication of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Jeanne Riccoboni, another novelist, wrote a public letter arguing its central woman was a man-monster, unreal; and since then George Sand’s Indiana in an allusive passage was intended to replace this false idea of women with another more real one (in Sand’s mind) of a rebel and depiction of the cruelties of society that made her retreat into a twisted dream.

Why should over the centuries artists not redo, and rework and show it in new relevant veins. It’s just so frustrating and leads film-makers into being timid or not doing a film they might want to do. I do like pastoral and alluring rococo playfulness, and the type Firth projects. He is often a poignant tragic figure (as in Patrick O’Connor’s A Month in the Country, Firth’s first major role). I am tireless in my defense of these commentary films and free adaptations because the refusal to give them validity makes for fewer, more timid ones, and less good and enjoyable art. In more and more academic film studies comparative studies of films and books written to understand the new work are being done. But they do not seem to have penetrated the public media sufficiently. What has to happen is film has to be respected more.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I probably should have mentioned Forman has a history of making unusual daring excellent films: One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest is the famous one; he specializes in biographies, like one of Francois Truffaut. He does not usually do film adaptations of older high status novels. This was his first foray and may well remain his only one.

http://www.us.imdb.com/name/nm0001232/

Ellen

— Elinor Mar 7, 10:29am # - I’ve read LaClos, I twice saw the Christopher Hampton play Dangerous Liaisons in London (on which Frears’s film is based), I’ve read the play, I’ve seen the Frears film (once), and I’ve viewed Valmont (twice, most recently a month ago).

I find your analysis very interesting, for I never entirely understood why Forman’s film was so (imo) underrated. I do feel that each version has merit, and can be judged singularly. And though I admire the play greatly, the Frears film is my least favourite version of all.

That said, in my view the novel rises above all and every adaptation will suffer by comparison!

— margaret Mar 7, 1:05pm # - Dear Margaret,

I can understand why you might think this particular novel, LaClos’s, is superior to these films and the play. My objection is to the assumption all high status books must be better than the film adaptations or cannot be improved upon or simply interestingly altered (even if the original book is very good).

This is fetishing books over films. In fact films convey an enormous amount of information, insight, depth, but it’s done differently and also different things are presented. And the film is the product of this era and us; the past is another country and the film must per force bridge.

For my part I find LaClos’s book misogynistic and the portrayal of Madame de Tourville’s death sentimental. It’s an imitation of Clarissa’s death in Richardson’s book, but it is a hollow inadequate one. Sand and Riccoboni disliked the portrayal of Madame de Merteuil and called it a man’s monster, a man’s nightmare.

I felt Forman’s portrait of Merteuil as acted by Benning more believable and his film the least misogynistic of the four works. I’ve seen the play. Forman’s emphasizes how the social order and its arrangements are what gives bad people power and leads most people to live amoral lives. This is consonant with other films of the era which criticized the amoral capitalist ethic of the Thatcher years.

Ellen

— Elinor Mar 7, 4:29pm # - I have never read the book, but have seen and admired both films, some time apart from one another, and am interested to hear how you find the interpretations vary.

I think it can often be a problem that if there are two adaptations of the same work around the same time, then one is praised and the other damned in comparison, even if the aims of the second director and writer are very different from those of the first.

There is also a free modern adaptation of ‘Dangerous Liaisons’, ‘Cruel Intentions’ (1999), directed by Roger Kumble and starring Sarah Michelle Gellar, Ryan Philippe and Reese Witherspoon. The names of the characters are kept, but the setting is changed to modern Manhattan and the characters are teenagers in high school, though I believe they are actually played by actors in their 20s. I haven’t seen this version, but it might be interesting to compare.

— Judy Mar 8, 6:19am # - PS – Just to add I’ve just discovered that my local libraries do have a copy of Sue Harper’s book in reserve stock, so I’ve ordered it and look forward to reading it.

— Judy Mar 8, 6:23am # - Both films (LLD and Valmont) have a preoccupation with masculinity not found in LaClos’s book. It’s striking how Firth’s Valmont projects feminity; in one dance sequence, he dances with 4 women (the aging Madame de Rosemonde, Cecile, Madame de Tourville and Madame de Merteuil) as Madame de Volanges and the musicians watch. He is the only male in the room and is the center of attention, proving himself. Malkovich’s Valmont seethes with intense anxiety to please and to control, to assert himself, and in the end fails before Glenn Close.

In her Ten Days in the Hills Jane Smiley has a joking passage (pp. 17-18) about how contemporary American films provide problems for actors wanting fully to emote because they have to be careful not to buck “the manliness problem.” They must not look non-manly. She thinks this is not found in European films and certain actors do escape it (Hugh Grant need not prove himself or win anything).

This anxiety (I'll call it) to prove manliness combines with the occasional or central -- depending on how you see the ruthlessness of just about all the women in Valmont and most of them in LLD. There is something strange about the women too. Meanwhile the angle at which we see the working class either sentimentalizes them or shows them to be greedy and drunk. These latter elements do not seem to me recent but can be found in older costume dramas from the 30s to the 50s.

E.M.

— Elinor Mar 9, 4:31pm # - Very interesting, Ellen. I haven’t seen either film in years, though I reread the novel from time to time.

First the epistolary form of the novel makes it difficult to adapt literally, so that’s not much of an issue in this case. I believe the reason why I liked the Frears version better was the acting. To me the Close/Malkovich couple was more powerful than Benning/Firth, but then it is only a question of personal fondness for the former.

I don’t remember Valmont being more anti-ancien regime than the other version, but again it’s been a long time. Social commentary is certainly a major theme of the novel, and in Laclos’s life. Time to see both again….

— Catherine Delors Mar 20, 5:03pm #

commenting closed for this article