Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_Mansfield Park_: Said, Rozema, and cultural studies redux · 7 June 06

Dear Harriet,

Last June, just around this time (the 5th to be precise), I wrote a letter about sex in films based on Jane Austen’s novels. I suggested that "What really distinguishes the filmic adaptation by Rozema of Austen’s MP

is the open sex, and lesbian sex and the lack ofwholesomeness in the attitudes towards the body." Now, Rozema’s MP is not the only reading of Austen’s novels to arouse strong antipathy. On C18-l Edward Said’s paragraphs on Mansfield Park in Culture and Imperialism have in the past few days prompted over 130 messages, in a large number of which Said’s book, Rozema’s film, and cultural studies were castigated. Some of the postings had content of such high merit, and were written with a kind of candour and explicitness hardly ever seen in published edited essays outside cyberspace that I would like to see part of the argument better known; from among these, I send an analytical defense of Said’s approach which connects it to Nancy Armstrong’s recent book, How Novels Think and my own and another intervention1.

Yesterday Abby Coykendall wrote:

"It would be helpful to review the supposedly decisive factual errors that have been alleged against Said: 1) misnaming a character (which concerns language alone rather the ideas that it signifies); 2) mis-describing a character in a book to which he devotes a single sentence (a Thackeray novel); and now more recently, 3) indulging in a Freudian slip, one that in itself is quite fascinating given the amount of scatology in the Bible and Dante alike. Indeed, Jonathan Swift would have loved that particular

Freudian slip, if only in giving us the opportunity to laugh at the hubris of authors and dogmatists, of humankind and himself, and of ourselves in turn in looking on.

The problem with all of these allegations is not their patent veracity or imprecision, nor even their origin in right-wing fantasy, but the implicit and malignant ‘therefore’ of the conclusions that dovetail and motivate them. Said misnamed a character; therefore, everything that he says about Austen is fallacious. Said misrepresented a character in a book which is clearly tangential to his argument; therefore, his more exhaustive comments about other books are no less fallacious. Said has a dirty mind and a devilish, slippery tongue; therefore, we should not countenance him when he notes the misrepresentations of Islam by Christian authors. The ‘therefore’ that I most object to is the following: Said is "political," polemical, a post-colonialist; therefore, he is subject to errors of fact and interpretation more than others.

All writers, all historians, all literary critics, and all C-18 posters are no less prone to the same epistemological and hermeneutic difficulties, cultural theorists or no.

Now as to the more substantive allegations, we still have the important question of whether Said’s primary claim about Austen and other writers in Culture and Imperialism is legitimate; namely, his argument that the country estate and the British empire are mutually implicated with each other and, in turn, that the British literary canon and imperialist ideology are mutually implicated with each other. In other words, Said seeks to add a third term – ‘Colony’ – to Raymond Williams’ famous dyad: the ‘Country and City.’

I believe that Said is correct in his main argument, although I also do believe that his application of that argument to Austen is something of a stretch. Indeed, Said himself (at least as I read him) seems to be aware that in selecting this particular novelist and this particular novel (Persuasion would have been far more fitting), he is making his own declared task of showing the connections between Colony and Country quite difficult. For him, that difficulty is in part the very point, since the connections between these two parts of the triad have been most violently censored, historically speaking. We can see the Colony and the City manifestly linked in, say, the ‘Royal Exchange,’ but for many, implicating the Country in that global traffic and that notorious colonial trade seems entirely another matter, especially since the Country is associated with ‘natural,’ homegrown profits and ‘natural,’ god-ordained hierarchies of power (agriculture, aristocracy, feudalism, and the picturesque pastoral).

Even Franco Moretti – and I agree with Davids Mazella and Brewer that Moretti is one of the most interesting critics of late – has a lengthy aside in Atlas of the Novel, in which he tries to disclaim the link between Colony and Country (one that originates with Eric Williams), tho’ from a Marxist point of view. Yet on this issue I am more persuaded by Michael McKeon in Origins of the Novel. At one point, McKeon argues that the presumed distinctions between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie (both in wealth and in caste) are much more nominal than substantive in our period.

Think of the younger brother of empire or the younger brother of the House of Commons, as well as the buying of estates or titles by families after auxiliary members garner colonial wealth abroad – as the Harlowes seek to do with the colonial proceeds of one of the uncles in Clarissa (a so-called ‘second father’). I must also confess, tho’ it may be a tad heretic, that I sometimes construe exorbitant acts of enclosure within Britain to be the equivalent of colonization, as appears to be the case with the second uncle (and the other "more than father") of Clarissa. Supposing her marriage, Clarissa would have consolidated a contrived patrimony from all three prongs of the ‘Colony, Country, and City’ triad – or, roughly speaking, the colonial empire, the paternal estate, as well as agrarian capitalism – a tripartite inheritance that Lovelace’s rape serves to displace, to whitewash, to mystify, and to apotheosize in a fashion that Nancy Armstrong has already documented in Desire and Domestic Fiction (and I suppose Eagleton as well in The Rape).

In any event, that colonial wealth subsidized the country estate and later provided the necessary collateral for the industrial revolution seems indisputable to me.

Now, as to the interesting article concerning the filmic adaptation of Mansfield Park, which was mentioned earlier as proof of Said’s ‘contamination’ of Austen studies (I have to take a slight detour before returning to the point above), one thing that was omitted in that author’s analysis is the important fact of generic intention and expectation. When Walter Scott writes Waverly, he is not held to the same standards of veracity as would be a historian. Given the genre of historical fiction, he is permitted "poetic license," permitted imaginative reconstruction, especially since every one knows that history neglects some vital facets of the real (the psyche, the individual, the everyday) that art and literature can help to fill in with relative ease, if only tentatively and speculatively in retrospect. (I believe that either Beattie or Percy makes similar claims in regards to ‘Ossian’ and folk literature more generally.)

Likewise, in adapting Austen’s novel, Patricia Rozema took a great deal of imaginative license, and she did so quite legitimately. That she explicitly aimed for stream-of-conscious magical realism rather than for factual, faithful, or literal replication of the original artwork is quite evident from the outset, whether it be with the intertwining of the author’s biography with the background of her characters or with the many, multifaceted allusions to other literary works (e.g. Sterne’s Sentimental Journey), some of which we have already discussed a long time ago on this list. (And, by the by, I do think that the impressionistic scenes of the colonies, with all of their gothicized exotica and erotica, owe a great deal to Blake, if not Goya.) Rozema makes these imaginative alterations and maneuvers blatantly, without shame, and indeed she does so in an exaggerated fashion so as to ensure that we will hold this film to the standards of ‘historical fiction’ rather than to those of history itself, to the standards of ‘magical realism’ rather than to those of realism itself. (This is not to imply, merely by way of contrast, that Austen’s novel is itself either historical or realistic in the first place, given that it too is an imaginative reconstruction.)

Now what is so fascinating about this director’s revisionist adaptation ofAusten’s original narrative is that, despite its magical realism and despite its stream-of-consciousness narration, the differential between the original and the adaptation is not additional fantasy, but additional factuality; not additional fiction, but additional reality and historicity. In other words, Rozema portrays Austen’s novel in a more realistic, historical, & contextual fashion than would a literal-minded (and hence fantastic and fetishistic) director aiming to faithfully and authentically adapt the same novel. It is also important to remember that with stream-of-consciousness narration, the association of ideas, not the facts per se, matters most, and hence the unsettling, uncanny contiguity of the slave trader and Portsmouth would make a great deal of sense on the level of collective consciousness (or, at least, collective unconsciousness), however incongruous upon the (no less imagined) stage of history itself.

To quibble with this director’s revision of Austen is ultimately to quibble with history itself. It is to retreat to a land of indelible fantasy; to return to a land of wish fulfillment, of spurious but satisfying family romance; to revive, if only in imagination, that nostalgic, utopian, and utterly fantastic space where literary "giants" and ingenious authors propagate generous humanists and gentile readers (all ethical embarrassments and illegitimate inseminations aside) for generation after generation onto futurity. It is, in short, it is to indulge, willfully and mistakenly, in the continued (and quite convenient) delusion that landlords like Sir

Thomas, our proxy fathers, patriarchs, and political leaders, are not also slave owners; or, for that matter, that those fops and factors populating the eighteenth-century London metropolis are not also, if only at times, absentee landlords capitalizing on (and continuing to capitalize on) the enclosure of England or the "glorious" conquest of Ireland …"

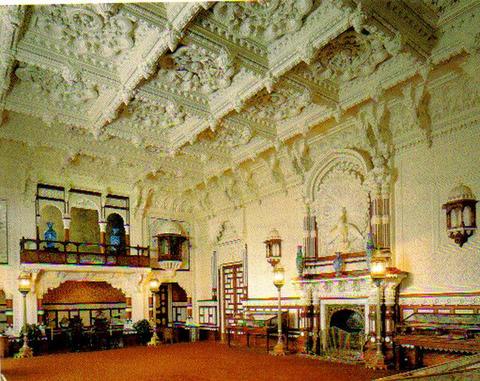

Orientalism: Durbar Room, Osborne House, Isle of Wight

She added today:

"In midst of turning to new things, I bumped into something quite apropos in the new Nancy Armstrong book How Novels Think, which I very much recommend from cover to cover. Below is a rather long quote from the book directly relating to our recent discussion.

My question for the economic or social historians and the political scientists out there is whether this kind of dialectical approach is warranted; i.e. is it fair to say that the pristine world of Austen makes sense precisely because of the chaos of the environs around it, or is this kind of reasoning by topsy-turvy inference essentially a stretch, historically speaking?

‘If the novels of Jane Austen represent the perfect synthesis of desiring individual and self-governing citizen, they also mark the moment when that synthesis crumbled under the threat of social rebellion, the rioting of dislocated farm workers, the amassing of unemployed laborers in the industrial centers of England, and any number of social factors that sorely challenged the fantasy of a society composed of self-governing individuals. Bounded on the one side by the traumatic upheaval in France of 1789 and on the other by the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, Jane Austen’s career coincided with momentous changes in the material conditions under which readers could imagine anyone achieving individuality. The widespread mechanization of labor, massive appropriations of common lands, migrations of unskilled labor to the cities, and the shift from the gold standard to various paper currencies together created the conditions for what Karl Marx would describe as the classic form of capitalism. [A]nother order of change occur[ed] at the same time, one essential, I believe, to the success of those transformations underway in the socioeconomic realm.

The change I have in mind enabled a British readership to understand itself as a stable aggregate of individuals, even as the new economy dispersed some of those individuals across the globe, redistributed other segments of the population within England itself, and brought in a steady flow of labor from Ireland. Inside the relatively prosperous household, a corresponding revolution was redefining the ideal English home as a field of objects that in part or whole came from elsewhere and were made by foreign hands. To preserve a sense of cultural coherence under such conditions, the novel had to refigure the social body so that readers could imagine it remaining English while taking in foreigners and foreign objects and extending itself onto foreign soil.

... Being British consequently ceased to refer to one’s place of birth, native tongue, or home and became instead a set of obligations and constraints that people could carry with them to other countries. This was the moment when Austen achieved her delicate synthesis of individual self-expression and social subjection by at once introducing some flexibility into the hierarchical world inhabited by her country gentry & subordinating her upwardly mobile heroines to the cultural standard articulated by her narrators." (6, 53-54).

Samantha Morton (Harriet Smith in the 1995 BBC Emma), a still closely imitating a late 18thC illustration of a lady reading

I added some thoughts and occasionally wrote playful and pointed interventions. Among these that

Said chose a novel by Austen because she and her writing are so fetishized as a sacred cow. Oftentime his book is brought up in the context of the small portion of it about Austen. He attracted attention that way, and also hit at a core totem. The choice of book too was partly determined by way the image of the particular book works: a metaphor for England as traditionally idealized is in the green landscape and great house (ever so beautiful, alluring &c&c). A famous critic about to die and in a wheelchair is quoted in a famous text saying he wanted to die dreaming of Mansfield Park.

One can find (as I suggested) a parallel semi-emphatic yet enigmatic pasage in Emma from which a similar argument might be readily made, but Maple Grove, the Eltons, Bristol merchants and the barouche-landau never do literally appear. The prestigious roomy barouche-landau of which Mrs E is so proud and the scrumptiously luxurious Maple Grove are probably owing in large part to slave labor. In the same marginalized but emphatic in the scene way as MP, in Emma Mrs E bristles (bridles) strongly when Jane Fairfax (not thinking of Mrs Elton or her brother-in-law at all) likens governessing to slavery. Mrs E smells a slight on her brother who is a Bristol merchant and is quick to say not all Bristol merchants are slave-traders. The lady doth protest too much.The house and park are central to the previous novel.

I had written the day before: Yes error-counting is a ploy, and it’s a common one. Arguing centrally with a writer’s thesis demands hard work from the writer. Worse yet it demands work from readers. Readers understand numbers and can jump with glee onto that sort of thing. That’s why it’s done.

Now what I really think is Emma does not deserve Mr Knightley. She’s just not good enough. Even she admits this. What should have happened is Mr Knightley marry Harriet Smith (who as we all know who have read Persuasions diligently for years) is the illegitimate daughter of Miss Bates by Mr Woodhouse. Proof positive: Miss Bate’s name begins with an H. And all those late night evenings over that sweet gruel—just the right consistency we are told. Lapping it up. Miss Fairfax should not have married that cad/cur liar, Frank Churchill, but emigrated instead. And taken Miss Bates with her.

Never fear I’m not about to commit a sequel. I just thought I’d offer my view.

One of the sanest interventions was written by Jennifer Golightly:

" ... Who says that novels can’t be works of entertainment but yet offer didactic messages or openly social commentary at the same time?

Frances O’Connor (Fanny Price) with Alessandro Nivola (Henry Crawford) in a scene that parallels Amanda Root (Anne Elliot) and Ciarhan Hinds (Wentworth) in the 1995 Persuasion

Many novels of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries do both, in many cases quite consciously. There are obvious examples, such as the novels of the radical period of the 1790s, but take for instance Richardson’s Pamela. The problem of that novel is based upon class difference: as an aristocrat, Mr. B is accustomed to simply taking what he wants, including any nubile young maids who happen to catch his eye. Pamela’s resistance as a member of the laboring class is in some senses quite extraordinary in its subversive potential. The marriage between the two at the end of the novel, a member of the aristocracy and a servant, seems to me tremendously radical precisely because Richardson spends the entire novel making the class difference between the two paramount. There’s ample evidence to suggest that eighteenth-century readers found the novel’s commentary explicitly social and potentially radical as well in the quite numerous responses, parodies, and imitations suggest, of which Fielding’s Shamela is the best-known. As others on the list have pointed out, the idea that Austen because she’s Austen is somehow exempt or above the social context and discussion that many readers are willing to perceive in other literary works has been proven fallacious I think in at least the last thirty or forty years of Austen scholarship—perhaps even longer.

And I must say, though I’m not meaning to be nasty, that simply because you prefer reading Austen in a more strictly textual manner doesn’t mean that the things being discussed here are ‘opinions’ that scholars or critics are arbitrarily "projecting" onto the literature. To say so seems to me to imply that literary scholars who approach literature from a cultural studies or literary historicist perspective make "interpretations" similar to the ones my freshmen come up with in their literary endeavours, most of which are problematic because they are opinions; i.e., totally lack any supporting evidence, and not reasonable judgements made on the basis of actual language and events in the texts.

To be more to the point (though I may regret this), I don’t understand why a variety of perspectives aren’t possible. I hesitate to even say this because I really don’t want to be at the center of a firestorm such as the one this list just weathered, but why do some list members seem so hell-bent on "my way or the wrong way" kinds of mentalities? Some of us undoubtedly prefer more strictly textual kinds of approaches to texts, some of us prefer cultural or historical or other approaches. This difference is precisely what makes this list so valuable and the discussions, when they work, so nuanced and enjoyable."

I agreed with Miss Schuster-Slatt’s sense of the threads expressed on Janeites. They were mostly anything but informative, insightful, "nuanced" or "enjoyable" (though a few wer). There was generally much more heat than light; under the pressure of the public forum, with people staking out extreme positions and much reactionary opinion (paradoxically anti-literary studies ultimately). The threads also continually degenerated into personal abuse. So often what is meant in a posting generally is picked up by various people in terms of each person’s particularities. This narrow egoism sometimes produces moronic threads, but alas this reaction is characteristic of many people. Finally, usually unacknowledged hierarchies outside cyberspace shape the way people treat one another in cyberspace, and the accountabilities of physical, social, and local and job- or clique-oriented real space do not operate to control behavior. So unhappily some people on C18-l who do not have high status there were not treated respectfully or courteously.

Nonetheless, here and there, there were postings which brought to bear on the issues swirling around and in Mansfield Park, an informed outlook, wide intelligent perspective and humanity, and I didn’t want what was said to be lost or buried from easily accessible reading. Said is not often enough defended in the way Abby did. So I’ve contextualized and sent hers onto you.

Sylvia

1 Abby and Jennifer have given me permission to quote their postings.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I wrote Abby after I put the postings up, and told her the technique I practised here (a common one for blogs) is called bricolage. She replied:

"Thanks, Ellen, and "bricolage" does seem a very apt term. The list seems to get worse & worse, eh? Maybe blogs are the way to go, tho I cannot give up my idealism that people would be reasonable if only the majority of them had the bravery to speak for themselves. In any event, thanks for carrying on despite it all!

Abby"

She’s right: it’s fear that silences many on C18-l. They are protecting their academic careers.

Sylvia

— Elinor Jun 7, 3:26pm # - From Mari W on Austen-l:

"Thanks for this, Ellen, a very interesting blog.

I rewatched Rozema’s MP recently, and I keep thinking, although she did radically change the book, it still feels like Jane Austen to me. Her aim seemed to be to bring out the dark undercurrents that are very present in the story as written, but difficult to transpose to the screen without major changes in how the story is presented.

Rozema consistently uses references to JA sources outside of the book in her screenplay; even to having Edmund use part of the defence of novel writing contained in Northanger Abbey.

So maybe changes are not the problem. Emma Thompson radically changed the dialogue in S & S yet the story was totally Austen like in feel. I recently read the diary she kept during the shooting of that movie; completely delightful :-)

The 2005 Pride and Prejudice made changes to the story, and in that particular case I felt that the changes destroyed the feel of the original story. The director and writer were attempting to make it melodramatic; the one thing Austen is most emphatically NOT.

Anyway, interesting stuff :-)

Mari"

— Elinor Jun 8, 7:15am # - Another from Austen-l:

I think by reading Austen one can get both a great story and an accurate picture of a slice of life- a narrow slice, granted.

I believe that Jane Austen dealt with wide ranging issues in her novels, but I believe that she carefully placed her novels in a constricted stage setting (the environment of the gentry of the time) a setting that she understood and that she described accurately. For example, one of the themes of Emma is tyranny—the many different circumstances that can result in a person having his/her free-will subjugated by another. Frank’s love of money allows his aunt to constrain his behavious. Jane’s love for Frank leads her to submit to a secret engagement and the resulting humiliation of silently watching Frank’s behaviour. Miss Bates financial dependency on the kindness of the citizens of Highbury leads to her assume the persona of the village idiot in order to ensure that she does not offend anyone. Harriet’s infatuation with the high life of Hartfield causes her to be led by Emma to refuse a man she really loves. The studied tyranny of Mrs Elton over Jane is horrifying ( we are forced to watch Jane squirm as Mrs Elton insists on fetching her mail or ruins Jane’s pleasure at Donwell by describing the luxuries of wax lights in the school room which will soon be Jane’s habitat.

In one of her letters., Austen said that she loved the author Clarkson. Clarkson described tyranny by describing the plight of slaves in the colonies. I think that Austen was dealing with the same topic but setting it in Highbury – a setting that both she and the majority of her readers could easily recognize. After reading other contempory sources, I believe that her picture of this little piece of Regency life was very accurate. Reading the Wynne Diaries, for example. I felt as if I were reading a first draft of Persuasion.

Catherine Lamb

— Elinor Jun 9, 12:45am # - The people on Austen-l have of course disagreed with Cathy and taken her to task for not knowing the difference between chattel slavery and what Jane experiences. Absurd. Cathy though gave an intelligent answer:

"Nancy, In my previus note to Austen-L I used the term tyranny to refer to a situation where a person subjugates another person’s free will. In that sense, the examples which I described fall under the category tyranny. To quote from my note: "For example, one of the themes of Emma is tyranny—the many different circumstances that can result in a person having his/her free-will subjugated by another. Frank’s love of money allows his aunt to constrain his behavious. Jane’s love for Frank leads her to submit to a secret engagement and the resulting humiliation of silently watching Frank’s behaviour. Miss Bates financial dependency on the kindness of the citizens of Highbury leads to her assume the persona of the village idiot in order to ensure that she does not offend anyone. Harriet’s infatuation with the high life of

Hartfield causes her to be led by Emma to refuse a man she really loves. The studied tyranny of Mrs Elton over Jane is horrifying ( we are forced to watch Jane squirm as Mrs Elton insists on fetching her mail or ruins Jane’s pleasure at Donwell by describing the luxuries of wax lights in the school room which will soon be Jane’s habitat. "

In addition to these examples of people being hindered from acting on their free will, I can add, Mr Woodhouse’s hypochondrical tyranny over his relatives. Catherine"

And I came onto Austen-l and replied:

Just to say (so she won’t feel alone on this – and it should be remembered only a tiny percentage of people on a list ever post), I know that Cathy is saying and I agree. The situation for Jane Fairfax is not better than say Fanny Price’s or the Dashwood sisters or the intense misery of Anne Elliot, but we are not allowed to see Jane fully. She remains in the margins of the text.

‘ll add (what the hell) no one ever said there is no difference between chattel slavery and Jane Fairfax’s social helplessness, servitude and shaming. To suggest that Cathy said that is to wilfully misunderstand in order to uphold establishment values as seen in Austen.

There is a big difference between chattel slavery and social servitude. So what? Social servitude can destroy lives just as surely. In the real world it might have destroyed a Jane’s. The parallel between the character and author’s name is not by chance. In fact such enforced servitude almost killed Burney.

Enough and more than enough

Sylvia

— Elinor Jun 13, 6:41am #

commenting closed for this article