Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

An Unsentimental _Emma_? · 12 December 06

Dear Harriet,

Since last I wrote about a film adaptation of an Austen novel, the 1979 BBC P&P, I’ve watched two more: the 1995 BBC P&P and the 1972 BBC Emma. This brings the number I’ve watched up to 12:

Transposition or analogies

1) Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s 1980 Jane Austen in Manhattan (an early James Ivory and Ismail Merchant production);

2) Whit Stillman’s 1990 Westerly Metropolitan;

3) Amy Heckerling’s 1995 Clueless (Paramount), starring Alice Silverstone.

Apparent fidelity

1) 1972 BBC Emma, directed by John Glenister, screenplay Denis Constantduros, starring Doran Goodwin, John Carson, Fiona Walker, John Eccles, Constance Chapman, Debbie Bowen, Timothy Peters;

2) 1979 BBC P&P directed by Cyril Coke, screenplay Fay Weldon, starring Elizabeth Garvie, Irene Richards, David Rintoul, Moray Watson, Priscilla Morgan, Judy Parfitt;

3) 1995 BBC P&P, directed by Simon Langton, producer Sue Birtwistle, screenplay Andrew Davies, Jennifer Ehle, Colin Firth;

4) 1995 Miramax Sense and Sensibility, Ang Lee director, Emma Thompson screenplay, starring Emma Thompson, Kate Winslett, Alan Rickman, Hugh Grant, Gemma Jones, Gregg Wise, Elizabeth Spriggs, Robert Hardy;

5) 1995 BBC Persuasion, written by Nick Dear, starring Amanda Root, Ciarhan Hinds, Susan Fleetword, Fiona Shaw, Sophie Thompson;

6) 1996 Meridian Emma, written and directed by Douglas McGrath, starring Gweneth Paltrow and Jeremy Northam, Sophie Thomson, Juliet Stevenson;

7) 1996 BBC Emma, directed by Diarmiud Lawrence, producer Sue Birtwistle, written by Andrew Davies, starring Kate Beckinsale, Mark Strong.

Frank reinterpretation

1) 1999 Miramax Mansfield Park, written and directed by Patricia Rozema, starring Francis O’Connor, Jonny Lee Miller, Alessandro Nivola, Harold Pinter;

2) 2005 Universal Pride and Prejudice, directed by Joe Wright, screenplay Deborah Moggach, starring Keira Knightley, Donald Sutherland, Matthew Macfayden, Judy Dench.

The only complete failure from the above is Jane Austen in Manhattan. From what I watched the last time I wrote a paper on film adaptations and what I’ve read about them (and the stage and screenplays), I’d say adaptations before 1971 (the first attempt at true fidelity by the BBC for Persuasion) were often failures, so it seems a genuine adherence to the original text insofar as this is possible (beginning in 1971) is responsible for most of the time producing a successful movie since (even if it has flaws). I put the success down to the high-minded thought that goes into creating faithful adaptation. The analogy when done similarly takes deep insight and creativity.

I find that despite the off-putting costumes (frilly, puritanical, dowdy, apparently based on the 1890s illustrations by Hugh Thomson) for many of the actresses (though not Doran Goodwin who was dressed exquisitely richly and repressed), I prefer the 1972 Emma to the two later Emmas, and the 1979 P&P to the 1995 P&P. I’m also leaning towards focusing for freer adaptations on the 1990 Metropolitan and 2005 P&P.

It’s easier for me to say why I prefer the 1979 P&P to the 1995 P&P. After watching the later film using a DVD in my computer, and being able to see the screen large and hear the beautiful music, I was impressed by Colin Firth’s performance in the second half of the film, and since the film was longer than the 1979 P&P, the directors and actors were able to present a film with gradually developed nuanced and powerful multiperspective scenes. Simon Langton spends much time developing Darcy and Elizabeth’s relationship, but the depiction of the mother by Steadman grates. She must have been directed to present a shrieking caricature.

Langton and Davies seem to think that the audience will not believe someone’s feelings can be outraged unless the person (Mrs B) shrieks the utterance sky high; you can’t be mortified unless the utterance or behavior is egregious and seen by a large number of people; I found the yelling made by Lydia and others hard to endure. Constant yelling of the nickname Lizzie when Elizabeth Bennet is often called Elizabeth or Eliza and Lizzie rarely. Lydia is insensitive in Austen; she’s not a rowdy hoyden who enjoys coarse shrugs and insulting others at every turn. And the wedding at the end just grated too: instead of spending more time on the scene between Mr B and Elizabeth at the end, we get this long wedding ceremony. I found myself irritated many times and felt relieved to be free of the noise when the earlier episodes came to an end.

This P&P also de-emphasizes the women’s relatoinships except for Jane and Elizabeth. There is real pity for Charlotte Lucas (Lucy Scott) now living in solitude and under the thumb of the hypocritical sneering Colllins, but apart from this compassion the film utterly endorses conventionally achieved heterosexual marriage as the central preoccupation and then occupation of a woman’s life. The depiction of Mary Bennet (Lucy Briers) as flat-chested and ugly, understanding nothing of her reading for real was extravagantly cruel.

By contrast, the 1979 P&P showed Elizabeth Bennet (Elizabeth Garvie) having a close relationship with Charlotte Lucas (Irene Richards); by treating Mrs Bennet with more respect, made her anxiety more sympathetic, and showed Elizabeth a friend to Mary; there was a moment of compassionate focus on the bullied, silent and isolated Miss Anne de Bourgh. The worst loss in 1979 film was the omission of the scene where Elizabeth’s father questions her on whether she loves Darcy, and says he worries lest she spend her life as he has had to do, with a person for whom he has no respect (or liking): Weldon and Coke both were determined to leave no sympathy for the father, but this same omission makes me wonder if they worried they might offend the audience by coming to close to their own realities.

How Weldon got so much of Austen’s language in was startling. It was hard for the actors, but I thought Garvie conquered it and spoke as if they were words she’d use. I cried and was joyous at the end. Garvie’s performance was perfect in context: the film was astonishing in its mimicry and internally consistent in the way the other literal representation of historical attitudes rarely are. Rintoul’s intense charged presentation of Darcy as at least consistent even if not likable. Austen’s character is a problematic one as he reappers too changed, with not enough presented inbetween. Austen did it better in Persuasion where Wentworth also undergoes change, but we see it in front of us and a long time went by to make it more creditable. Irene Richards is a dignified moving Charlotte.

The difficulty in saying why I so loved the 1972 Emma is a product of its complexity. Like the 1979 BBC P&P the people who made it did not find it necessary to deny any serious intentions, and in fact admitted to reading criticism, the novel, and taking the project seriously. Glenister took a more modern view of Mark Schorer’s famous essay on Emma herself:

"Emma, then, is a complex study of self-importance and egotism and malice, as these are absorbed from a society whose morality and values are derived from the economics of class; and a study, further, in the mitigtaion of these traits, as the heroine comes into partial self-recognition, and at the same time sinks more completely into that society."

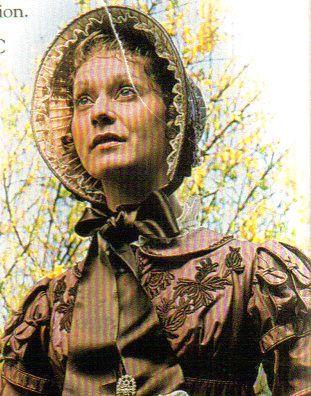

Glenister and Constantduros produced a film where Emma is genuinely kept at an ironic distance from the viewer and we are often led to dislike her. (Anthony Trollope said of Austen’s Emma that "the heroine is treated almost mercilessly.") Glenister had read Mark Schorer and came up with a psychoanalytical reading of Emma as (given her father and isolated flattered position and high but naive intelligence) understandably neurotic, and chose Doran Goodwin as an actress who conveys the biting intensities and frigidities of Anna Massey. A characteristic passing still from from the film:

This kind of presence combines with erudite voice, the careless snobberies, elegance and high intelligence of Susan Hampshire types, only the edges of her voice are grating. Doran Goodwin plays arrogance and kindness all at once; her mobile face turns from cool rigidity and blindness to sudden eager intense desire:

She is not beautiful; she is better than that: she has a face fascinating to look at.

Emma’s taking over Harriet was not treated as light comedy; it’s rather a kind of dangerous light farce (we are watching two clueless fools). The first episode of the six ends in a slightly frightening scene where Emma is dictating a letter to the naive and confused Harriet (Debbie Bowen), rejecting Robert Martin.

Not that this production marginalized the woman question. While (like other of these films, except in the case of Fay Weldon where a woman wrote the script), it seems the directors and writers consistently (and therefore deliberately) leave out all lines which focus on the powerlessness of women to obtain security or respect unless they find a good rich man (not an easy thing it’s emphasized), nonetheless, this Emma had many long pivotal scenes where the women characters predominated and interacted with one another directly, creating a multiperspective which enabled the viewer to explore and enact worlds of women. Constance Chapman made a believable Miss Bates: she reminded me of my mother-in-law in type. Much as I find Jeremy Northam in the Meridian 1996 Emma intensely attractive (sexy, alluring), I have to admit that John Carson, sober, quiet, older, the gentleman brother, is much more like the Mr Knightley I used to imagine when I read Austen’s book.

There was a daring scene between Carson and Goodwin. When Christmas comes, and Mr Knightley walks over to Emma is cuddling her sister Isabella’s baby girl, the scene occurs upstairs in a darkened bedroom. Goodwin is dressed in a low-cut gown and the way she holds the child suggests a woman breast-feeding. Carson’s gestures towards Goodwin and baby are a combination of protective, tender, and aroused. In the film as a love relationship between the two replaces the opening father-scolding-daughter and evolving brother-sister ones, the affection they feel is expressed through words and controlled courteous gestures, gallant on his part, and accepting on hers. But here we have a deeply sexualized scene, more so than many of the kissing scenes in the later films.

It does seem de rigueur for the proposal in all 6 novels adapted to film to occur outdoors at the end of a long walk with the hero and heroine walking side-by-side (this 1972 Emma, the 1979 P&P, the 1986 NA, 1995 P&P, both 1996 Emmas, the 2005 P&P). This Emma added the feminine motif of having Mr Knightley and Emma enter a pavilion and sit down together before they begin to speak. Alas there is no photo available for this scene.

Fiona Walker is the best Mrs Elton I’ve seen thus far; while the Meridian 1996 Emma had the pleasantest and wittiest of the Mrs Eltons (Juliet Stevenson who does undermine Emma’s status as warm loving heroine), the paradigm Austen set up works best when Mrs Elton is monstrous, something of a persistent insensitive bully over Jane (Ania Marston, dressed as a Jane Eyre type). Glenister did this to make someone in the story worse than Emma, and then (deepening the meaning) backtracked to have Mrs Elton’s sarcasms accurate.

For an example of the multivalences here, take the film’s penultimate scene where we at first watch three hands playing cards and then the camera moves to reveal the players are Mr and Mrs Elton and Miss Bates (who we are given enough insight into to see she knows that Frank Churchill has come to court Jane Fairfax). The compromise marriage between Emma and Mr Knightley, with Mr Knightley going to live under Mr Woodhouse’s roof had been announced. Mr Elton (a handsome Timothy Peters; in this production Elton is not a caricature) says of Mr Knightley’s going to live at Hartfield, "Better him than I," to which Fiona Walker replies persuasively she’d never seen generations living together this way to work out. This is the only production of all 4 Emmas (I include the 1996 Clueless) to present Mr Woodhouse as genuinely at first refusing to hear of Emma marrying anyone, even Mr. Knightley. Walker was a brilliant Ruth in Ayckbourn’s Norman Conquests.

The 1979 P&P did something peculiar: it seemed a self-contained imitation of the later 18th century insofar as it could, and asked us to enter into Elizabeth’s grief over Lydia’s possible self-destruction and remorse (yes this production does go in for punishing the heroine as guilty of something). Not the 1972 Emma. The scene with Mr Elton in the carriage was presented as a man who won’t believe in "no" and becomes physically aggressive at these signs of "coquettishness" from Emma. Here is Goodwin just before or after it becomes obvious Mr Elton is aggressively pursuing her:

I love the beautiful winter cloak. I also chose this still because it shows Goodwin’s subtle projection of quiet distress and confusion at Mr Elton’s behavior during the Christmas party to which Harriet cannot come.

In the sense of modernizing somewhat the 1995 P&P produced a relentless quarrel scene between Elizabeth Bennet (Jennifer Ehle) and Lady Catherine de Bourgh (Barbara Leigh-Hunt) where Elizabeth’s stance felt genuinely radical as she denied the right of the family system to tell her where her happiness would lie. The 1995 P&P did some justice to how women betray as well as support one another, an important theme in Austen too.

I called the 1972 BBC Emma "unsentimental?" because against the overall conventional plot-design and images of women as pregnant, mothers, desperate accommodating subordinates, obedient daughters (and we see Emma obey her father in scenes where his demands are selfish and unreasonable, exclusive), and the happy ending of a toast in the room, is another discourse of pragmatic hardness, using one another, performative behavior which cuts across all the love relationships. This is especially in the behavior of Robert East as Frank Churchill, here not a cad, simply relatively heartless, rather like Austen’s own John Dashwood in this.

We are also spared the obligatory super-celebratory (solemn in the 1995 P&P) wedding that seems to appear in all these high-status melodramas (even where there is no such thing in the eponymous book anywhere). Yvette said the film was done as a drawing-room comedy in part, and she was right: all four couples appear last in the Hartfield drawing room toasting one another with wine, with only poor Miss Taylor forbidden to drink wine by Mr Woodhouse. She is ordered to drink milk because she is nursing the new infant. We are to be glad to see Emma protest and be able to hope Mrs Weston is not excluded from adult independent humanity and can have a glass of wine too.

I’ve still to read Whit Stillman’s screenplay for Metropolitan and reread Mansfield Park, but I will probably focus on it. My sense is the film brings out the vulnerabilities and high nobility of Fanny Price and Anne Elliot as a presence in her heroine, Aubrey Rouget (Carolyn Farina who later played Janey Archer in Scorcese’s Age of Innocence); and its use of motifs from Emma (like the demand for candour as a way of invading the privacy of others which backfires) and Persuasion (deep melancholy).

As I wrote a while back, I loved the expressiveness of the 2005 Focus P&P. All the stills I’ve found show their faces intense, vulnerable, anxious, many close-ups too. I liked how Wright and Moggach developed the sexual aspect of Mr and Mrs Bennet’s relationship, their sympathy for Mr Bennet (Donald Sutherland), and turned back to the 1939 Wuthering Heights to model its codes (though I’ve now discovered that in the 1995 P&P Jennifer Ehle does stand high on rocks overlooking a archeaological green landscape) in lieu of the 1940 trivializing optimistic P&P.

Probably my favorites among all the films remain the 1995 Miramax S&S and the 1995 BBC Persuasion (though this film has jarring performances and is flawed, partly because the book has problems), but both have been discussed recently at length by others and I can’t use them to make the points I want to, for I’ve also decided where my energies will go. I’ve also begun to find the criticism I’ll use, but I’ll save that for another letter when I’ve thought more. I have no title as yet, and that’s a sign I have no thesis as yet, just a chosen terrain.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Dear Dr. Moody,

I can’t tell you how much I’ve enjoyed reading postings from someone who, like me, sees much of interest in those BBC adaptations from the 1970’s and 80’s. My main criticism of that particular adaptation is the casting of an actor who is really too old to play the part of Mr. Knightley, though he plays the role in a way that makes more sense to me than Mark Strong’s portrayal in the 1999 version.

I teach a course called "Jane Austen in Film" in which I shamelessly subject my students to Fay Weldon’s Pride and Prejudice and Ken Taylor’s excellent Mansfield Park in defiance of Ellen Belton’s pronouncement of the former’s being "less interesting" as a subject of comparison with other adaptations. They are important works for us to look at if we’re serious about questioning the nature, purpose, and even the possibility of film adaptation.

I’ve recently written an article on this very subject and am trying to figure out where it makes the most sense to send it. Thank you for letting me know I’m not the only one looking at this material seriously.

All the best,

Nicola Minott-Ahl"

— Sylvia Dec 13, 4:37pm # - Dear Professor Minott-Ahl,

I’m equally rejoiced to find someone else taking these earlier adaptations seriously I wrote about the 1983 Mansfield Park in a review published by the Intelligencer which I’ve put on the Net:

http://www.jimandellen.org/austen/janeausten.onfilm.html

My view is the dismissal of the earlier films comes from their not using modern computer technology, not hiring charged sexy box-office stars, and also the costumes do not combine modern fashion with the later 18th century in such a way as to keep the actors looking sexy—and young. There's also a strong tendency to dwell on films that have become sociological events (pop hits) and attribute art to these and forget those which were not.

I’m writing an essay too. I hope to have a place in a coming anthology. I suggest trying Persuasions. There is also Literature/Film Quarterly. Another prejudice anyone writing about films made for TV is the assumption they must be inferior to films made for theatres. So it’s hard to get essays on film adaptations of novels in print in sheer filmic journals; you have to go to a place where there is real interest in the books from which the film is adapted.

I particularly like your comment: "They are important works for us to look at if we’re serious about questioning the nature, purpose, and even the possibility of film adaptation." Yes, these earlier films are sincere in their attempt at faithful adaptation: they want to be faithful and yet they know they must adapt. And studying them shows us the problems encountered because the attempt is so real.

Good to hear from. Thank you for your comment.

E.

— Sylvia Dec 13, 5:49pm # - Edith Lank (of Austen-l) wrote:

"For my money, Doran Goodman was a poor Emma. Rather than the robust picture of adult health Mr. Knightly describes, she was mousy, inert and wimpy. Harriet, OTOH, was perfect, much better than the tall and hefty brunette valiently attempted by Toni Collett in 1996.

—Edith"

— Sylvia Dec 14, 6:20am # - Julie Lai wrote:

"I’ve seen all six parts of the 1972 Emma and find it as

interesting, intelligent, and moving to watch as any of the later

1990s films."

I have an older version of _Emma_put out by BBC. Not sure if that’s the 1972 version. Anyway, everything was very well done. My only gripe about that version is that the hero and heroine looked too old for their part. (The newer Emmas looked much prettier…)

Julie Lai"

— Sylvia Dec 14, 6:21am # - Dear Edith and Julie,

It was Goodwin’s acting I thought so good, and the script and presentation which made Emma strongly dislikable at first and never let up in allowing us to see her blindnesses and manipulation of other people for her own delectation—except of course her father. The father as a querulous blind tyrant, meaning well, but controlling all around him, was also beautifully brought out. It was the only Emma film thus far to take seriously the problem of Emma marrying anyone who wanted to maintain an independent life apart from the father; we had the scene suggested by Austen where the father says no.

I myself tire of all the talk of the looks of the actors and actresses. They are important, but the truth is Austen’s descriptions are general. I protest when a blonde (Austen will tell color of hair) actress is substituted for a heroine we are not was not fair (blonde) or we get someone very thin (the recent P&P had anorexic young women) when we are told the character was plump. But in the case of Samantha Morton, an excellent actress, it didn’t matter that much. It’s not for me a beauty contest with my tastes the reigning standard. I am allured by Jeremy Northam, but John Carson looks much more like Austen presents Mr Knightley.

I don’t enjoy watching teenagers play these roles, partly because I think Austen poured so much of herself into them that a character like Elinor is not 19, but 19 going on 39.

Thank you, Lai: As I wrote above, the dismissal of the earlier films comes from their not using modern computer technology, not hiring charged sexy box-office stars, and also the costumes do not combine modern fashion with the later 18th century in such a way as to keep the actors looking sexyand young.

There’s also a strong tendency to dwell on films that have become sociological events (pop hits) and attribute art to these and forget those which were not. The 1940 P&P and 1995 P&P were sociological events of importance in Jane Austen studies, the romance world, the development of historical romance serials (and movies made for theatres), and so now it’s hard to find a copy of the 1979 P&P; this has nothing to do with its equality. The 1972 Emma is not sexy, no sexy women (we had Gretta Scatchi who is beautiful, to my eyes far more beautiful than the kinky-sex Gweneth Paltrow, for Mrs Western); the costumes are not sexy; that’s why it’s an embarrassment.

Movies are fundamentally atavistic in their means and reach. Virginia Woolf saw this immediately in her early review-essay, "The Cinema" (1926), which appears online:

http://www.film-philosophy.com/portal/writings/woolf

People say the savage no longer exists in us, that we are at the fag-end of civilisation, that everything has been said already, and that it is too late to be ambitious. But these philosophers have presumably forgotten the movies.

Sylvia

— Sylvia Dec 14, 6:30am # - I was thanked offblog for the comments I wrote on C-18L on film adaptations of Austen (some of which appear here) and a Ruth Perry essay, "Sleeping with Mr Collins," Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature, 5:2 (1986):185-202.

"Ellen, I wanted to say thanks for your recent reference (on C 18L) to a Ruth Perry article that I found extremely useful—I enjoy your postings and find many of them helpful.

best wishes,

Sally O’Driscoll."

Perry brought out beautifully different attitudes in the 16th through 18th centuries in Europe (from our our) towards a wife’s sexual experience with a husband in bed). Simply the woman was supposed to accept sexual intercourse as what she was to submit to provide children. This helps explain why we do not feel how Mr Collins violates something especially sacred at night, only what a bore and obstacle his presence is to any enjoyment or friendship with other people Charlotte can have during the day.

Perry also argued female friendship was central to Emma, more important in fact than the women’s relationships with the men. This may be, but the problem is Austen emphasizes the destructive side of female friendships, not their importance as a support system. We see how women relate first to their position in a hierarchy controlled by men, and only afterwards to other women in this hierarchy (according to their place as well as their characters). So while every remake of Emma thus far makes the women's relationship to the men more important and take up far more space and scenes vis-a-vis those with women in the film thatn they do in Austen's novel, the thrust of the movies is only (a big only) subtly wrong.

E.

— Elinor Dec 14, 12:57pm # - Offblog:

Dear Ellen,

In your article [Jane Austen on Film; or, How to Make a Hit -- http://www.jimandellen.org/austen/janeausten.onfilm.html], you make an important point about the importance of the camera and editing process in imparting a sense of momentum in Austen adaptations that are not central elements in Austen’s narrative. I too think the main differences between the pre-and post-1995 Austen adaptations can be seen as differences in technology (and budget). I also agree with the idea that filmmakers who create these adaptations are offering a certain amount of escapism—ironic considering the fact that Austen didn’t see herself as writing escapist fiction.

I hear that Andrew Davies has written a screenplay for another version of Northanger Abbey but that efforts to produce the film have been dogged by all manner of difficulties. I would love to see that film made, especially in light of your discussion about the effect technological advances have on the presentation of Austen’s stories. The BBC version starring Katharine Schlesinger has as many problems as points of interest and it would be interesting to compare the two.

On another note, as someone new to publishing, your suggestions are most welcome. I appreciate your generosity in offering suggestions as to where I might offer my article. Many, many thanks.

Best regards,

Nicola

— Elinor Dec 15, 5:56pm # - Dear Nicola,

That’s an interesting idea. Most of these comparative essays which go through a number of films whose title is that of a single eponymous article take as the basis of their discourse how "close" this or that film is to the original book. The problem is both criteria are subjective: we have the critic’s understanding of the book and then the critic’s somewhat impressionistic understanding of the film. Most do not do as Monica Lauritzen does in her superb study of the 1972 BBC Emma (I assume you’ve read that) and carefully distinguish and describe concrete story events and hinge points and character types (large elements) apart from a considered catalogue of the subtler nuances of discourse, object, and face closeups.

You would compare the cinematic techniques of the two films to one another. If you go over to IMDB you will find that the database now says that this recent NA is finished and will soon be advertised.

http://www.us.imdb.com/title/tt0844794/

It’s dated 29 November 2006, and labelled "postproduction." I assume they are telling us the truth.

Let’s keep in touch.

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 15, 6:02pm # - From Austen-l, Julie Lai:

"The 1972 Emma

The person playing Jane Fairfax in that version is just perfect.

I loved the scene where Emma let slip her suspicions about Knightley and Jane Fairfax. The book has Mrs. Western in the scene (and it is outdoors?), but I can easily imagine Knightley handing Emma her scissors at that moment. Knightley managed to show he wasn’t pleased while smiling (sort of).

I’ll also add that the 1971 version of Persuasion has the perfect Anne Elliot. And I easily see Elizabeth Garvie as Lizzy in the 1980 P&P."

— Elinor Dec 16, 12:23am # - Dear Julie,

Not only did Elizabeth Garvie look the part, she acted it beautifully. As far as I can tell, Fay Weldon’s play is the one that most closely took over Austen’s words. While in the context of a novel, and one published in 1812, the dialogue seems naturalistic, it’s not at all, and especially not in our era. Yet Weldon was able to speak these lines with depth. She believed in her role (a problem in these serials is the actors don’t believe in their roles). At one point I burst into tears at a piece of dialogue that was wholly outdated in the norms or values at its heart (Lydia "ruining" herself); Weldon did take over too strongly the punish-the-heroine motif. Weldon’s Elizabeth is remorseful, and guilty over her rejection of Darcy. I don’t know how much Weldon was aware of this. By contrast, Davies’s Elizabeth (Ehle) was not guilty or remorseful, only increasingly regretful as she fell openly in love. Still Garvie made it believable.

I have looked and it seems Weldon’s play is not in print nor ever was. Would anyone care to correct me, and if so, let me know where one can get a copy of Weldon’s play outside BBC headquarters or its library?

Here’s a still of Elizabeth Garvie:

http://www.jimandellen.org/ellen/1979ElizabethGarvieElizabethBennett.jpg

Her expression is of the more upbeat, determined-cheerful but not at all serene character Austen projects. Again by contrast Ehle projects serenity which seems to me wrong for Austen and part of the unresolved contraditions of Davies’s play.

Doran Goodwin’s expressiveness could project Marianne Dashwood:

http://www.jimandellen.org/ellen/72EmmaDoranGoodwinEagerIntense.jpg

As acted that moment she embodies Marianne Dashwood wandering in the grounds of the Palmers, seeking Combe Magna (this is as presented in Thompson's S&S)

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 16, 7:16am # - From Austen-l:

Ellen wrote: Weldon’s Elizabeth is remorseful, and guilty over her

rejection of Darcy. I don’t know how much Weldon was aware of

this. By contrast, Davies’s Elizabeth (Ehle) was not guilty or

remorseful, only increasingly regretful as she fell openly in

love. Still Garvie made it believable.

I watched the 1980 BBC P&P just this week, and it did strike me that in the 1995 version, there is comparably little expression of Elizabeth’s self-realization after she reads Darcy’s letter—that she was wrong to believe Wickham so easily and quickly. She does say to Jane, "Until that moment, I never knew myself," as in the text of the novel, but that’s not until quite a bit later. I didn’t get the sense that Elizabeth berated herself for being prejudiced and blind.

I will add that I did enjoy Garvie’s performance and found it closer to the character than Ehle’s, and while Weldon’s screenplay was overall more

faithful to the novel, there were a few wrong chords (e.g. Elizabeth saying, "There are few people whom I really love …" to Wickham, Elizabeth running to Pemberley in search of her uncle, Mr. Collins’ very tall hat, and so on).

—Laura Joldersma"

— Elinor Dec 18, 1:25am # - From Austen-l:

"I prefer all the older BBC versions to the newer ones. There’s a subtlety that I enjoyed in these versions that I can’t find in newer ones.

The one thing I don’t like about the 1980 P&P, however, is how they cut short several key dialogues (Darcy-Elizabeth by the piano at Rosings; Darcy-Elizabeth at the Parsonage, etc.) Also a bit annoying: Lizzy running to Pemberley and the abrupt ending. But I can easily put up with all that when there’re so many good scenes to make up for them: Charlotte and Lizzy laughing over Mr. Collin’s hat, or Lizzy kissing her mom when Mrs. B. thought Jane’s dying of a broken heart to be the best punishment for Bingley, or Ms. De Bourgh’s reaction when she was shoved towards Mr. Darcy’s direction by her mom. (She never speaks, but her look says it all.) I also loved how the camera moves away from Darcy and Lizzy at the end, to give them a little privacy. All in all, the 1980 version is the best in my book too.

Julie Lai"

— Sylvia Dec 18, 1:26am # - In reply,

I find all the Austen adaptations interesting.

There are a few poorer ones (perhaps the 1971 Persuasion is weak; the 1985 S&S is said to be dullish); the pre-1971 ones depart from Austen without trying for an individual art work but rather to embody a formulaic kind of genre, "screwball comedy" for the 1940, drawing room comedy for earlier plays. Things grate in the different ones: yes leaving out just that poignant scene and instead giving us the long solemn wedding ceremony in the 1995 S&S.

I like the freer adaptations (Clueless, the recent or 2005 P&P which is quite free and adds interpretations, the 1999 MP which is a sort of commentary); those which fill out characters left suggestive (the 1995 S&S is true to the conception of Edward and Brandon’s characters, depressive melancholy the first and man of sensibility the second, but fills them out and makes them alive; I feel the same is attempted for Darcy in the 1995 P&P); and I like the ones which attempt fidelity with an interpretation either consonant with Austen’s own more closely (the 1972 Emma) or accenting something (the 1980 P&P deliberately blackened Mr Bennet and that is why the scene where in Austen he spoke so poignantly of his desire for Elizabeth not to spend her life with someone she couldn’t respect; it had a pro-woman question agenda in the way lines originally given Mr Bennet were given Irene Richards as Charlotte; real sympathy is given Anne de Bourgh as bullied and depressed; Mary is not cruelly laughed at as she is in all the P&Ps but the 2006 where again she is made understandable and sympathized with).

I would play mix and match for favorite performances: Doran Goodwin as Emma; Emma Thompson and Kate Winslett for S&S (the whole 1995 S&S cast), Fiona Walker and Juliet Stevenson for Mrs Elton though for different reasons. I thought Sophie Thompson just wrenching as Miss Bates insulted, Samantha Morton as Harriet stole the show from dull Kate Beckinsale. I started watching the 1983 MP and find Anna Massey beats them all out and steals the show for Mrs Norris. As for Fanny Price, the best is Carolyn Farina as Audrey Roguet in Metropolitan: she is really close to Fanny as I pictured and feel her in Austen. Francis O’Connor was told to combine the Austen of the Juvenila with some contemporary stereotypes of what makes a strong woman and somehow turn that into Fanny sheerly through the acts the role demanded.

Some of the male actors seem to me more like what Austen had in mind (John Carson as Knightley), but then I sometimes simply out of personal taste prefer another actor even if he’s unlike Austen’s. After all these are films in their own rights, works in themselves. So I like Jeremy Northam (as I’ve said) as Mr Knightley and the long scene of proposal in the Meridian 1995 Emma though only a couple of suggestive hints are like this in Austen’s parallel scene.

So it depends. One might say they given us insight into Austen’s texts by their differing successes and flaws.

E.M.

— Sylvia Dec 18, 1:40am # - From Juliet Youngren on Austen-l:

"What’s amusing is that Ehle has become so entrenched in the collective consciousness that people have somehow gotten the idea that Elizabeth’s figure is supposed to be busty and curvaceous, not "light and pleasing."

Juliet Youngren"

— Sylvia Dec 19, 1:08am #

commenting closed for this article