Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Revealing Similarities & Absences in two S&S films · 26 December 06

Dear Harriet,

This will be the last of my letters about film adaptations of Austen’s novels until I return to the project to write the essay. I may write about other film adaptations of novels and film studies in general since I’m doing this project not because I love Austen’s novels (then I’d write about them) but because 1) I was told about a volume where an essay on Austen adaptations would be welcome; 2) I know Austen’s novels well and have written aboutthe adaptations before; and 3) have become fascinated by film criticism and want to study films themselves seriously. I also plan to write an essay on film adaptations of Trollope’s stories, for which, starting some time next week, I’ll watch at least 3 one hour episodes a week for a long time to come.

This letter is about how comparing two close versions of Austen’s _S&S reveals ow all popular films simply instinctively avoid the hardness and harshness of great books’ perception of what existence for people is like in favor of offering a sentimental award for precisely what makes us most vulnerable in life. We also glimpse how central to the pleasure of watching films is the erotic charge of watching certain kinds of sexy stars embody favorite characters.

I finished watching the 1986 S&S on Christmas eve. This is the 7 half-hour episode faithful adaptation version directed by Rodney Bennet, written by Alexander Baron (using Dennis Constantduros’ 1971 script for an earlier TV S&S), starring Irene Richards, Tracey Childs, and Diana Fairfax as Elinor, Marianne and Mrs Dashwood; Bosco Hogan as Edward Ferrars, Robert Swann as Colonel Brandon, Peter Woodward as Willoughby; Amanda Boxer as Fanny Dashwood. Thompson’s 1995 version has so displaced the 1986 it’s as hard to find stills from it as it is for the 1983 MP.

Here is a rare one from early in the film: it occurs when Edward (Bosco Hogan) and Elinor (Irene Richards) are just falling in love after Edward has first come to stay at Norland park:

1986 S&S Elinor (Irene Richards) and Edward (Bosco Hogan) with flowers and a book

It’s akin in meaning to the many stills of Edward (Hugh Grant) and Elinor (Emma Thomson) falling in love at the same time in the recent 1995 Miramax S&S, directed by Ang Lee, screenplay Emma Thompson:

1995 S&S Elinor (Emma Thompson) and Edward Ferrars (Hugh Grant) walk in front of Norland Park

What makes a study of the two films against the book so revealing is how similar is the approach of both films. Emma Thompson owes more to the 1986 S&S than has been realized. Both films fill out the characters of Edward and Colonel Brandon (Robert Swann) as a depressive, intense, intellectual young man, and emotional reading man of sensibility, devotion, who has been deeply hurt, respectively. Both emphasize the same romantic scenes over the satiric and even the same linking ones and interpolations. For example, we have Thomas, the servant, informing the family he has just seen Mr and Mrs Ferrars and leading them to believe mistakenly Edward has married Lucy Steele; in both films the developing romance between Marianne and Brandon late in the film comes from Brandon reading aloud some effective romantic poetry to Marianne.

Both make a woman-dominated movie where the relationships between the women in general and the sisters in particular make up far more of the scenes than the heterosexual romance ones, though the two sisters’ relationship is less idealized (Marianne is sent up as foolish, often spiteful, stubborn, wilful, cold and yes jealous of Elinor’s power and status as the older sister) and it’s the three women who are focused upon, as can be seen by one of the few stills to be found:

1986 S&S, Marianne (Tracey Childs), Mrs Dashwood (Diana Fairfax) and Elinor (Irene Richards) as they are displaced from Norland Park

A major difference is in the 1986 film Willoughby is permitted to appear just after Marianne passes the crisis of her illness and tell his story in the same melodramatic mode as Colonel Brandon does in both films. This is not as important as might be thought as in the 1995 S&S we are asked to see Willoughby as intensely remorseful at the end, regretting his loss, and after all as having loved Marianne even if he didn’t know it at the time.

1995 S&S, Willoughby (Gregg Wise) looking down from height at happiness he missed

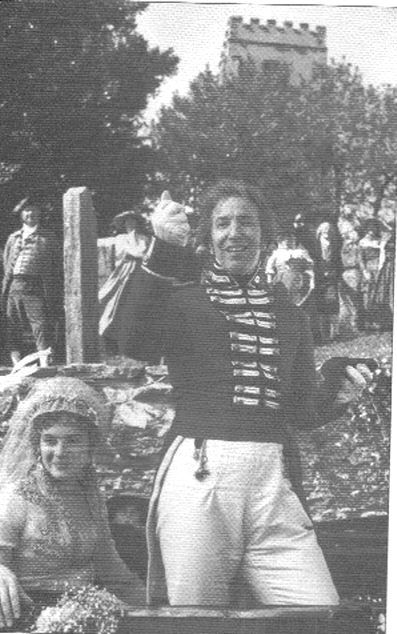

What I want to highlight is how in both films the character who was originally an acknowledged partial loser in some way in the novel is made triumphant in the film. The now familiar trajectory of Thompson’s S&S shows Colonel Brandon who was deprived of his original beloved, Eliza Brandon, and mocked and derided by Willoughby and Marianne as old, boring, someone who no one remembers, becomes the savior of the family, providing a fulfilled true happiness for Marianne. From a melancholic withdrawal, he has become a gorgeously arrayed soldier scattering gold coins to the air.

One of the last stills of the 1995 S&S:

1995 S&, Colonel Brandon (Alan Rickman) in final triumphant moment (the coat is bright red)

The final moment of the 1986 S&S is given over to Mrs Dashwood (Diana Fairfax) who watching Elinor and Edward walking deep into the woods from the cottage, and Colonel Brandon and Marianne talking over a set of books he has brought to her for them to read together, says emphatically: "My children!" Unfortunately I have no still of Diana Fairfax at this moment.

Nothing like either of these scenes is in Austen. The tone of her moral lessons is caught up in her remark on Lucy Steele’s marriage to Robert Ferrars (now the heir):

"The whole of Lucy’s behaviour in the affair, and the prosperity which crowned it, therefore, may be held forth as a most encouraging instance of what an earnest, an unceasing attention to self-interest, however its progress may be apparently obstructed, will do in securing every advantage of fortune, with no other sacrifice than that of time and conscience."

Austen’s Marianne gradually grew to be devoted to Brandon, Willoughby was by no means inconsolable, Mrs Dashwood could now dream over Margaret’s courtships, and "let it not be ranked as the least considerable, that, though sisters, and living almost within sight of each other, they could live without disagreement between themselves, or producing coolness between their husbands".

This triumph of the apparent loser is important. As Patricia Meyer Spacks (among others) has demonstrated, the real losers of the novel are Eliza Brandon and Eliza Williams. Brandon would not have the estate but that his father forced his heiress-cousin, Eliza Brandon, to marry Brandon’s older brother, a brutal, selfish, hard man she fled from to a lover who abandoned her after she was pregnant with Eliza Williams; his brother died and now her daughter is an outcast because she succumbed to Willoughby whom the first film appears to suggest we should blame as much as Willoughby who emerges unscathed (rich and socially acceptable as ever). As with Austen, Baron & Constantduros and Thompson dismiss the reality the prosperity of all is dependent on the exploitation of a powerless and then vulnerable woman.

B&C and Thompson go further, though, to make us think rewards come to those who behave in self-sacrificing pro-family and pro-private property system ways. They picture gratified motherhood (the 1986 S&S) and glamorous militarism and glittering money (the 1995 S&S).

The sudden gush at the close of S&S is particularly telling.The 1986 S&S is not a sucessful movie since it closely follows melodramatic and romantic aspects of Austen’s novel while omitting the harsh and hard satire, the actual register of Austen’s comedy in this early book. The 1995 S&S has repeatedly been criticized for adding benevolent comedy and kind romance, for making the film have light jokes and frivolous clown figures like Sir John Middleton and Mrs Jennings:

1995 S&S, Sir John Middleton (Robert Hardy) and Mrs Jennings (Elizabeth Spriggs) fall all over themselves in eager kindness

Thompson was wiser than literary people know. The addition of the sweet child, Margaret, was a necessary antidote.

1995 S&S, Margaret Dashwood (Emilie Francois) delighted

It is simply unacceptable for popular films, especially on TV, to capture filmically the real hard core perceptions of the experience of life of great books. By contrast, the popular film must present as winners those who conventional actions have made them vulnerable in the first place. What Thompson did was lighten up the intensely emotional core of the book.

The 1986 S&S remained truer to Austen’s extant text. Marianne is shown to have hard unattractive impulses, which lead to Elinor’s intense agon. B&C brought out fully the cruelty and arrogance of Fanny Dashwood and Mrs Ferrars, the gothicism of Marianne’s near death, the melodrama of the love stories, but drew the line at trying to capture in any real way Austen’s undercutting hard assessments and irony. Since no distracting or contradictory comedy replaced these, no softening of the characters shown self-destructing, we end up with a film with an unrelieved didactic sentimental core.

The 1986 film also hired actors who project unaggressive, non-macho presences. They are all three types gentlemen—like LeCarre’s Justin Quayle (constant gardeners). The 1986 Willoughby is no rake, Brandon no military man; the 1986 Edward is a man of delicate kindness.

1986 S&S, Elinor (Richards) and Edward (Hogan) in their final still

The similarities, absences and problems for modern audiences and literary critics in these two films make clear real qualities in Austen’s books and the problems all film-makers have in adapting great books into filmic commodities.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I’ve just watched the 1995 S&S again (it came on television the other day), after recently hiring the DVDs of the older adaptation, so am very interested to read your blog comparing the two, Ellen.

I also like the stills you have chosen very much.

I also preferred the 1995 version – although I can see that it does lighten and soften Austen’s satire, I love the additions such as Margaret’s character, and agree with you that these touches are probably needed. I was also interested to see how Brandon becomes more central in both adaptations than I remember him in the book – though central isn’t really the right word; it’s more that he is constantly there in the background, a brooding presence watching over Marianne. In the book I’ve always felt a pang about her being married to him – as though she and her emotions are being tidied away – but in the movie versions I think we see that he is a romantic too and they are better-matched than I’d thought. (I can see I will have to read the book again this year.)

An added pleasure for me with the 1995 version is the presence of so many "stars", such as Kate Winslet, Emma Thompson, Hugh Grant and Alan Rickman. Somehow it does add something to have actors I already know and like taking on the form of characters from favourite books – as long as the casting is appropriate, of course. Also of course the sheer beauty of the landscape in this version – and the costumes – are important to the whole experience of watching it. I do like the slow pace of the earlier version and the space it gives for scenes which have to be missed out of the Thompson version, but it doesn’t have the vividness and memorable quality of the 1995 movie.

Do you know if the DVD of this version has many "extras", making of featurettes etc? If so I might be tempted to treat myself.:)

— Judy Jan 11, 5:22pm # - Dear Judy,

I’ve not tried the DVDs Laura bought me for Xmas of all the older film adaptations. They were sold as a set of 6 during Xmas here in the US. I doubt there are any extra features in them. They seem put together in the least expensive way possible. They are all simply packed in a light white and pink background with feminine designs and a still from each on the front cover.

We’re in agreement about how Thompson and Ang Lee’s version did improve on problems in Austen’s novel by developing the males (out of hints and suggestions and adumbrations in Austen), Margaret (who may in some earlier version been in the novel more), by changing the comedy to softening benign humor, kindly in tone for the most part.

I’m glad you bought up the slower pace of the earlier one though. The same holds very true of the 1983 MP.

I’m waiting to hear for my abstract to be approved and feel I must write the 2nd paper on Halkett first—as it makes me nervous to think I have a paper to read aloud and it’s not done yet. However, I know that part of my argument will be that the films bring out qualities or structures and meanings in Austen we may not have seen without the film.

So I never realized really how Brandon is the character who saves them all. Spacks says the irony is he does it through property he inherited from his cousin, the ward of his father sold to his brother so the property would come into their branch of the family. Nonetheless, it’s he who does it. In my paper where I argue the novel was originally epistolary I suggested Brandon wrote to Mrs Dashwood in the last part of the novel. I’ve always felt the marriage of Brandon with Marianne was right. To me Willoughby was a cad; I could never get over how he says he didn’t need to tell Eliza his address; she knew where he was; the unfeeling thick-skinned indifference of it revealed the man’s core nature. Maybe it was seeing Brandon as a man of sensibility like one in Radcliffe’s Romance of the Forest that made him the romance figure for me before either movie.

However, if you think like me that Wharton was thinking of S&S when she wrote Summer had had her abandoned and pregnant heroine end up marrying and then reluctantly going up to bed with an old man, you could suppose that Wharton agreed with your original feelings about Marianne not marrying the young handsome man.

Ah. Isabel came in to watch the older film, the 1986 one, when she heard that Brandon was on the screen, and she stayed to watch that actor. She’s a good reader. The people who make these intelligent films have good instincts as readers. Or maybe having to make a strong plot-design out of the original story for a movie makes them see things we don't.

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 11, 11:43pm # - Thanks for your further thoughts on S&S, Ellen. Just hastily to add it isn’t that I wanted Marianne to marry Willoughby – I agree with you about his behaviour – but that I wasn’t happy about her marrying Brandon because of the age gap and because I thought it seemed a bit abrupt. Maybe I will feel differently when I read the book again and pay more attention to Brandon.

I’ve just checked the information at Amazon and I see the DVD of the 1995 movie does have some additional features – an audio commentary by Ang Lee and co producer James Schamus, another audio commentary by Emma Thompson and producer Lindsay Dorans, two deleted scenes and Thompson’s Golden Globe acceptance speech. There isn’t a "making of"/behind the scenes featurette, though, which are the sort of extra features I like most. (I had wondered if there might be a "two-disc special edition" with a lot of this type of material, but it seems not.) I tend not to get round to listening to commentaries because it means watching the whole movie again and is time-consuming, but it would be interesting to hear their thoughts on some of the choices they made.

None of the older BBC series seem to have any special features on the DVDs.

— Judy Jan 13, 3:15am # - I meant to add that I’ve never read Wharton’s ‘Summer’ but am interested to hear of the link with S&S. If I get round to rereading S&S this year, I’ll try to read ‘Summer’ straight afterwards.

— Judy Jan 13, 3:17am #

commenting closed for this article