Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Lyrical Melodrama: the 1979 _P&P_ · 12 July 07

Dear Harriet,

I thought I might write some preliminary thoughts down about the 1979 P&P as a beautiful work of art.

I notice a lot of people who come over here to read the reviews of Becoming Jane Austen in all its forms, move on to the 1995 P&P. So in the spirit of providing an alternative point of view: having watched Weldon, Powell and Coke’s 1979 P&P very slowly over several days last week, I’ve been reconfirmed in my early apprehension of this film as aesthetically of very high quality. It’s like Aaron Copeland’s Tender Land: a lyrical melodrama.

Last scene of Darcy (David Rintoul) and Elizabeth Bennet (Elizabeth Garvie), their faces open to one another in earnest grave confiding conversation at long last

The 1979 P&P (produced by Jonathan Powell, directed by Cyril Coke, written by Fay Weldon, production design Barbara Gosnold, costumes Joan Ellacott), is in feeling, nuance and theme superior to the 1995 P&P. The Birtwistle, Langton and Davies film is broad and uses caricature; except for the leading hero and heroine, they provide generalized types: as in the case of Suzanne Harker’s quietly effective performance as Jane, in the 195 P&P, it’s the individual actors who provide through face and gesture what nuance there is. In Weldon we have depth & nuance throughout, especially in the dialogue, & a women-centered approach. The evolving relationship between Darcy and Elizabeth is of two earnest, grave, and reserved people, self-contained yet capable of slow change. Elizabeth herself is at the center of the movie.

The 1995 P&P places Darcy’s development before us; he is an Oedipal figure who earns his right to the heroine. The 1979 P&P keeps the hero at a distance, as in this shot in the second assembly the only close to show him full face where he looks fondly at her:

The subject of the 1979 P&P is Elizabeth inside her family. We see a heroine in transit, deeply troubled, only one part of whose conflicts is solved by her escape from home to become an intelligent, kindly, ethical, & very rich man’s wife.

There are at least 5 sequences of inner soliloquy with Elizabeth our angle of vision and our terrain. Here are three stills from just one:

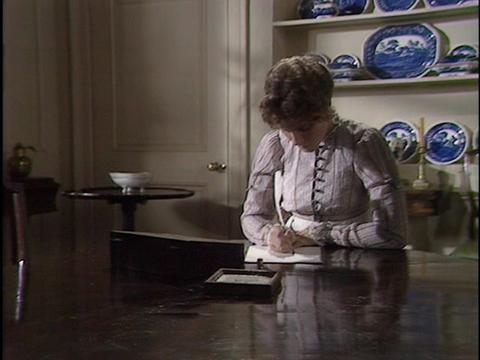

Here she is deeply disturbed to learn Darcy was at Lydia’s wedding so sitting down to write in the now familiar front room of the family:

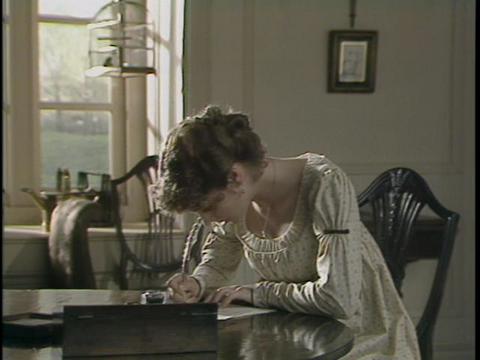

Here is the middle still of her grasping Mrs Gardiner’s letter, walking to the window, reading it intently:

And here she is looking deep within:

There are many repeating motifs. Darkness, cool grey light on the downstairs room where much goes on. We see the household at night in that room, Mr (Moray Watson) and Mrs Bennet (Priscilla Morgan) putting out the lights in his study when they go to bed. Dark and yellow light. Plans are made there in the different rooms. A birdcage with a bird seems to stand for the whole family in the front room by yet another of the many thin-lined Freilicher-like windows.

Here is Elizabeth attempting to write hurriedly to Charlotte (Irene Richards) before her resentful mother interrupts:

Many many window scenes, like this of Jane (Sabrina Franklyn) at the close of Episode 1 (Bingley [Osmund Bullock] has gone):

She gazes out into now empty space; just before this we see him staring out a windowed-door knowing he has to leave her, yearning for what he is losing:

When Mr Collins (Malcolm Rennie) arrives, he is seen on the other side of yet another window-barred door:

Dotted throughout the film are scence of tiny figures lost in green landscapes:

Charlotte and Elizabeth walking together in the fields near Rosings and Hunsford

As in the 1995 P&P the added scenes come between famous moments or chapters, so viewers alert to criticize, are lulled.

I’ve now read Weldon’s Down Among the Women, Female Friends, half of Darcy’s Utopia, almost all of her Letters to Alice Upon First Reading Jane Austen, and about half-way through the stories of Polaris and Other stories. (Coming up will be Auto-da-Fay and Praxis.) These confirmed my sense that the 1979 P&P presents a world of women repeatedly (as the 1995 P&P does not): we see them in groups in many different situations in the house, doing things women did and do. In many it’s clear they are without power, and in a state of waiting or marking time.

The Bennet women are subject to Mr Bennet; we see them facing him asking him for this or that several times. He may have a special relationship with Elizabeth, as in the repeated scene of them playing backgammon (or chess) together in his study:

but he can and does say no to her and just about get out when in an early scene when she wants him to help stave off her mother’s pressure on her to receive Mr Collins’s advances.

His refusing face before he says get out of my library

Her facing his refusing face.

There’s a deep unease in the 1979 film—the father and mother’s relationship ends the film and it’s not good. I liked that. We take Mr Collins seriously when we visit Hunsford. Charlotte is under his thumb. I loved how Weldon gave Kitty (Clare Higgins) a character: she really does want someone to esteem her and her father picks on her because she’s vulnerable to this need. In his bitterness and frustration after he returns home without Lydia (Natalie Ogle), we see him think of something to say which will make her cry:

He picks on Mary (Tessa Peake-Jones) too, but she withstands him better. Mary is made pleasant at times, smarter and not continually sour faced (as in the 1995 P&P which stigmatizes reading women). She opens the film running out for a letter. I liked that. She is eager for life and puts her face to the sun and begins to run:

By no means does the film blame Mr Bennet though. He is depicted as a man intensely estranged from his wife. We see several strong quarrels with him leaving the room suddenly. While the situations are those of Austen’s book, the lines and stance of the characters are far more anguished. Here is Mrs Bennet looking back at him, hard:

And there is this poignant moment when Elizabeth returns from Hunsford, and he says, nothing much happened, & thinks, nothing much changed between us, but from her face we see otherwise:

He admits the rightness of her warning to him not to let Lydia go (though he bitterly blames her mother for Lydia’s conduct as Mrs Bennet does him in return if only to get back momentarily as when Lydia marries, she shows she felt no remorse for what she did, only regret it seemed to be ending badly).

Now one might have thought Weldon would produce a witty kind of comedy but no she is tending more to the Chekhovian feel of lingering—as in a long scene of genuine talk between Elizabeth and Mrs Gardiner as they stroll in a lovely classical picturesque landscape garden:

This conversational and walking scene ends Episode 2 and we see Elizabeth feel she is moved emotionally by her memory of Wickham, but we the viewer may find what’s moving her is this conversation with Mrs Gardiner (played beautifully by Barbara Shelley). The first scene of Mrs Gardiner has her and Elizabeth in the group of women talking and preparing clothes. The third Elizabeth and Mrs Gardiner talk in the inn after Mrs Gardiner realizes Mr Wickham is a scroundrel and Elizabeth turning to Darcy. We see them airing and drying their dresses together. Weldon must’ve felt she had to stay sentimental—or was enabled to using a mask and release aspects of herself she doesn’t do in the fiction where she’s “Fay Weldon.” So we get Elizabeth’s intense remorse and long soliloquys in the second part develop a character of depth and emotion different from Austen’s own.

There is a scene between her and an unnamed lady in the last part where the sense of what’s happening and what’s said reminds me of a scene late in Persuasion—about women’s and men’s constancy. There the lady prevents Elizabeth from leaving a place for Darcy to sit next to her. Elizabeth acquiesces and then somehow catches his eye and they converse briefly. Elizabeth must turn back to the lady who has no real conversation or thought, but only petty resentments. Elizabeth is talking to herself when speaks of how she doubts male constancy. She has tried to reach Darcy in the manner of Anne Elliot and failed. Darcy does not try seeming unaware or not anxious about his ability to contact her when he wishes. He is quietly comfortable drinking coffee nearby.

It’s the result of his character (and shows his power in the relationship as the man too) that the final coming together happens so simply: Darcy sends her a letter via a maid. We are not allowed to see (Weldon knew this kind of departure from the original hinge point would give the idiots and envious a chance to bray), but I wish we had that text. I don’t imagine Wentworth’s, but rather a plain quiet note asking her to join him in the park. Darcy’s explanation of himself in the earlier film is much more about how at Pemberley he didn’t want her to think him mean and genuinely humble in a way, open. Weldon is moving P&P towards Persuasion_. Rozema moved MP towards satiric comedy.

The romance idea that women are intensely monogamous and even unlikely to fall in love deeply a second time, is swept away. In Weldon’s P&P Elizabeth really does like Wickham (Peter Settelen) very very much and could as much have gone for him as Darcy (one of the promotional stills is of her remembering Wickham, not Darcy). Colonel Fitzwilliam (Desmond Adams) is also a fully developed figure (literary, subtle, with views on the reviewing, opera, people) and we get the feeling she could have entered into a real companionship with him

He looking down at her, smiling

She sympathetic back

That is, had he not let her know he is not a man to marry without a good deal of money to enable him to continue his pleasures. In a bitter moment (much bitterer than any of the other films or Austen’s text), Elizabeth tells Jane not to worry about her if she’s very lucky years from now she may meet another Mr Collins (that’s in Austen—refers to an actual proposal by a dull man she rejected in life). That’s unlike all the other films—except Ruby in Paradise and the first Bridget Jones (I include 27 films here which means the free adaptations too).

Some techniques: in this movie there are numerous tracking shots—and just about all of them follow Elizabeth. The most astonishing is the long one where Elizabeth makes her way to Netherfield Park in the pouring rain—against her mother’s wishes, and ultimately without Mary, who deserts. First we see the two as tiny figures against a grey-blue sky: they trudge up the hill, turn down a path, then up near the tree. There Mary refuses to go on. Elizabeth then goes it alone, determinedly walking ever closer across the meadow, getting smaller and smaller as the house looms larger and larger. Here is the central moment of this as Elizabeth turns and looks at Mary’s stubborn face: she is trapped between a house she dislikes entering and one without Jane, i.e., no inalienably true and intelligent companion:

If this were a drawing, it could be Adeline St. Pierre in Radcliffe’s Romance of the Forest, driven, fleeing, filled with cares.

In numbers of the other Austen films since the mid-1990s the heros actually become the center: the 1995 P&P is not alone in this. The longest tracking of Elizabeth’s inner reflection is while she sits and reads Darcy’s letter (and we hear his voice-over and then hers—just as in the 1995 P&P only Jane’s story is told first) and we watch him walk away and the camera re-angles the landscape over and over again.

The distanced or zoom shots present the figures in this landscape as tiny; we move closer to them, and then have close-ups and then the camera moves far away so we have a far angle shot of what the character is seeing. Then again a tiny character in the landscape:

Here Wickham’s story comes second for it is only then we get flashbacks from Elizabeth’s mind as she recalls a long walk she took with him while they half-played croquet:

Glimpsed only from the side, we still see how earnestly she gazed back at his easy talk.

There are quietly effective objects (and one comic one, Mr Collins’s absurdly large hat given him by Lady Catherine [Judy Parfitt] so he and Charlotte may spend the day cutting rushes in a river on a hot day) in the mise-en-scene. Many of the scenes occur in Elizabeth’s bedroom and we are continually shown the girls looking out her window or sitting on her window sill. The scenes where they crowd and squeeze in a kind of ball of arms and bodies and legs are comic, yet touchingly memorable. They are so eager for someone to come. They are unable to go out by themselves. They are pictured as a tightly-knit group again and again. In the house, around the table, coming down the stairs, tying their bonnets before going out, in Elizabeth’s room talking to one another, bringing news, consoling, and yes occasionally being spiteful. Overall they are kind to one another until Lydia leaves for Brighton and is afterwards presented as continually hostile, condescending to the others. A motif in the film is women’s arms intwined in one another’s, especially Jane and Elizabeth, Charlotte and Elizabeth.

One example of the above: the moving scene between Jane and Elizabeth where after Bingley has returned and is openly beginning courtship again, Jane again tries to avoid admitting she’s in love with Bingley. Weldon brings in lines from S&S about why should Elizabeth try to persuade her she loves more than she admits she does and then back to P&P. Weldon’s Elizabeth’s words about not being able to teach what’s worth learning becomes a pointed remark about how she, Elizabeth, needs to learn not to care so intensely whether Mr Darcy shows up (the last episode has several long soliloquy scenes with voice over from Elizabeth):

Juxtaposed immediately to this scene where running after a man, a need for him is seriously challenged as dangerous, we see Mrs Bennet standing eagerly in the hall staring at the door and window, just waiting. A couple of seconds goes by and then her face lights up with joy and relief and off she goes to tell Jane who is immediately ecstatic and runs to get ready.

(As pictured in this scene I can recognize myself in potentia as a Mrs Bennet. I would stand there by the window or door near the time staring and hoping and I wouldn’t give a damn what was his character :). For me it would not be just or even mainly the money.

There are scenes of quiet awareness between Darcy and Elizabeth and their relationship does grow. Here is a dramatic one of the pair of them striken together as Elizabeth tells of Lydia’s elopement:

The Weldon team’s depiction of all the minor women in the story, but especially Mary & Kitty Bennet, Anne de Bourgh (Moir Leslie) make me want to write a series of short stories on them using the characters as they emerge through Weldon’s prism. Lady Catherine’s battle with Elizabeth is superior because the terms of the battle are understood from within.

While it’s true there was a mistaken decision to direct David Rintoul in a way that kept him stony faced, a proud aristocrat who has trouble socializing, is guarded (the lines about implacability are omitted in this P&P), his face does melt more than once, registers disdain, hurt, embarrassment, attempts at conversation, gradual change from someone who only sees himself to someone who realizes he must show he knows his is not the only consciousness worth knowing and pleasing. Here he is flinching as Elizabeth rejects his first proposal:

He is not as openly emotionally vulnerable as Colin Firth’s Darcy. As Darcy when Elizabeth comes to Pemberley, David Rintoul is eager not to show he loves, but that he is not so mean as to resent her, but as he tells her when they come together in the last long scene, he soon then understood he loved her—for having woken him up to other people. And once he gets to take his tall hat off in the final long walk, he’s as soft, gentle and laughing as any Elizabeth might want:

More generally, I feel Austen’s book has made Weldon give her characters more emotional depth and convincing realism. In Sarah Cardwell’s study of Andrew Davies’ TV dramas, Cardwell suggests that there are adaptors who produce better or more interesting work when they write an adaptation than an original screenplay. Cardwell does not present this negatively (they needed the “great” writer’s source to enable them). She says it’s that such adaptors are compelled to regard the story world and characters in a more distanced and controlled manner, and can can combine their own veins of thought and feeling with very different ones to produce more interesting amalgam. The second author’s work (as in this 1979 film adaptation of P&P) becomes subtler and style, tone, gesture and implication are resorted to for self-expression.

Of the work I’ve read by Weldon thus far, I feel that the screenplays she did as adaptation are in some ways superior to her uncontrolled satiric work. In a way one could regard this as a poet trying to write within a restrictive form, say a sonnet.

Weldon is a post-feminist like Alice Munro (whose Runaway plus “The Bear Came over the Mountain” and “The Children Stay” I read last month). Both writers present women as they vulnerable and mostly only taking a job as a sideline to their lives in their families; the women are long-suffering, desperate, unable to effectively stand up for themselves, insecure, of low status compared to men, embedded in disempowering or demeaning & often destructive conditions. And Weldon tells stories which remind me of Munro’s: Weldon has one in Darcy’s Utopia about a young woman who leaves her husband and two children for her lover and “the children stay” with the father. It’s a strikingly hilarious and refreshing treatment; and yet there is this plangent desperation as she wildly fucks away with this no-goodnik, and knows whatever she does, her children will blame her.

To read Weldon is like reading an upside down Alice Munro (as well as other sentimental writers). What’s emotional pain and grief and loss in Munro becomes deadpan anguish in Weldon Weldon’s work thus connects to Helen Fielding’s. For example, she has her heroines repeat and experience as a truth that men are constitutionally unwilling to commit, but want women to serve them selflessly.

Down Among Women has some astonishingly good passages, raw satiric dark:

“And this monstrous jagged stranger, her huband, lies nightly like an incubus in the dark beside her, inserts his being into her, and grows his child within her.” (p. 53)

A pregnant heroine has a dream of a supposedly primitive world which is our modern one:

“Susan hovers for a moment on the borders of that other terrible world, where chaos is the norm, life a casual exception to death, and all cells cancerous except those which the will contrives to keep orderly; where the body is something mysterious in its workings,which swells, bleeds, and bursts at random: where sex is a strange intermittent animal spasm; where men seduce, make pregnant, betray, desert; where laws are harsh and mysterious, and where the woman goes helpless.”

Weldon shows doctors to be bullying women, breast-feeding to be yet more exploitation and allowing oneself to be deprived of all freedom (you have no time, your body under the control of a creature who is all ego and appetite). Weldon describes childbirth in all its excruciating pain.

Now this sensiblity is contained so that in the 1979 P&P it becomes quiet lyrical melodrama.

************

A realistic plan? I told Abigail I am wrestling to get my outline into manageable compass. I am really trying to work out a mechanical plan for an essay, such as I had for a book when I did Trollope on the Net, one I could follow and at the end of each “turn” write a section.

I’ve decided the thing to do next is tell myself I am writing an essay on three superior earlier faithful film adaptations. The context is a development of TV drama and within in the Austen movies. I will do these three: the 1972 Emma, at heart a distanced ironic comedy (it owes a lot to 1960s criticism); the 1983 MP, a melancholy paean to Cowperesque values; and the 1979 P&P, a lyrical quiet permutation of Weldon’s consistently women-centered material which without the restriction, controlled pace, and sentimental ethic of Austen’s story matter tends to wacky or semi-fantasy fast-moving angry satire.

To study the Emma film I need to reread Austen’s Emma, go through the movie more slowly & alertly (critically) than I’ve done yet, then reread the book by Monica Lauritzen; proceed to write. Then reread Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, and then exactingly view the 1981 Sense and Sensibility said to be Constanduros’s play with little change. Then in the French manner insofar as I can do it, write. (I have read a play and book of short stories by Constanduros, and much Austen criticism of Emma and Sense and Sensibility.)

Then I should turn back to the 1979 P&P and reread Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, watch the film consulting my notes and this blog, then watch (if I can manage it) Weldon’s episodes from Upstairs Downstairs (“On Trial,” “Your Obedient Servant,” and “Desirous of Change” are the episodes she wrote), her Life and Loves of a She-Devil, read her Auto da Fay (an autobiography), and then write.

To study the MP film, I need to reread Austen’s MP and rewatch the film carefully with the novel nearby. Though it sounds like madness I think the next thing to do would be watch at least some or all of the Jewel in the Crown episodes_ (as Taylor wrote the plays for this stunning series), study Cowper, Elizabeth Inchbald’s play. Then in the French manner insofar as I can do it, write. I have read Jan Fergus’s excellent essays, discovered the producer Jonathan Powell also produced the 1982 Barchester Chronicles (which I have seen, also three of the LeCarre TV adaptations, including Tinker Tailor which I have seen). I’m glad Cyril Coke, the director, has done so few of these TV dramas (including 5 episodes of Upstairs Downstairs, which I’ve seen and The Duchess of Duke Street, Gemma Jones, which I’ve not).

This would not be a procedure for a book. I won’t do that unless I get a letter back from the editor at Continuum, saying he is willing to revamp my old contract. Then whatever work I’ve done towards the paper will turn into the book, but I need not worry until the man contacts me.

This could be the core of a paper on faithful adaptations. I have identified 10 or 11 (I’ve moved the Meridan 1996 Emma (by McGrath, starring Paltrow and Northam, into to my analogous or critical adaptations column). If Abigail were patient, I could hope to get it to her by Xmas :)

But first I must finish Sarah Cardwell’s book on Andrew Davies’s adaptations and report to you on that.

**************

What is the true heir to these early brilliant faithful adaptations among the 2005-2007 films? Logically it would be the 2007 faithful Northanger Abbey. In mood the closest is the melancholy 2005 P&P. But for depth of feeling developed and subtlety which all these three are I’d give it to the analogous expressionist 2007 Persuasion, which also ends in (albeit a bit skimped upon) formal gardens of a great house.

Pemberley, the gardens.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Janeites, Catherine MacFarland:

“I would agree about the 1979 film being the most faithful and I’ve loved it for years.

But I enjoy the 1995 film as more of a fantasy though Mrs Bennett is played so stridently that I’m embarrassed to watch her (in her in-public scenes)”

To which I reply:

I did not say this film was great because it’s faithful. Indeed I didn’t say it was particularly faithful. If you had taken in the content of my blog, you’d have comprehended that I’m continually showing where Weldon has made a different original filmic work of art.

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 13, 7:25am #

commenting closed for this article