Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

A revealing switch or omission in the _Emma_ films · 29 July 07

Dear Harriet,

I wrote an unusual “foremother poet” posting for Wompo this past Friday, one that will not fit the usual format. So I should probably put it here, lest it be lost. What is shows is it matters that every single available Emma film we have is by a team of men (directors, screenplay writers, producers are all men).

To my case in point: While reading Jane Austen’s Emma this week, I was struck by a lovely passage in the novel and by its not ever having been dramatized in any of the film adaptations of Emma. I think this is not just an omission, but a revealing switch. The overlooking of this scene odd since usually everything is done that can be done to make the Austen materials intensely romantic.

I must contextualize the scene, show how it is embedded in Austen’s story:

In Austen’s novel, Frank Churchill has secretly bought a piano for his clandestine beloved bethrothed, Jane Fairfax, and managed to get some time alone with her in Miss Bates’s, her impoverished aunt’s lodging room before Emma, the egoistical blundering rich heroine of the novel with her dumb friend, Harriet Smith, in tow, as well as Mrs Weston, Frank’s mother-in-law, and Miss Bates, Jane’s aunt, all come into the room. He is probably warned about their entrance as the aunt, Miss Bates, is not so dumb as others might suppose, and calls out very loudly as she brings the others up the narrow dark stairwell.

The piano Frank Churchill (Robert East) bought Jane Fairfax (Ania Martin); we are in Miss Bates’s lodgings and see Frank’s hand on the keys, Miss Bates’s hand and skirt next to him (from Emma, BBC 1972)

In Austen’s book, Frank wants Jane to play songs they had enjoyed together while on holiday at Weymouth. He must somehow in front of this crowd let her know he wants this as well as say why.

You need to know no one in the room but Frank and Jane knows the piano is a gift from him and that the others have been encouraged by Miss Bates to think it’s from Colonel Campbell her guardian. This is improbable because he would not distress her by creating attention-getting mysteries; also while he has brought her up, he has not been willing to overspend so lavishly in this way on her. Emma has shown herself willing to start a rumor it could be a clandestine love gift from Mr Dixon who is married to Jane’s best friend; this is base treachery from woman to woman: by spreading such a rumor, Emma is endangering Jane’s reputation and relationship with her one close friend. The previous evening Jane and Frank had been to a party where there had been dancing, but they had not been able to dance with one another, rather Frank had as a coverup danced with Emma, and understandably (and callously, perhaps self-indulgently) excited Jane’s jealousy. Jane has exhibited considerable embarrassment before the others and strong reluctance to play any of the songs which also came with the piano. So he speaks before them all to her thus:

“If you are very kind,” said he, “it will be one of the waltzes we danced last night;—let me live them over again. You did not enjoy them as I did; you appeared tired the whole time. I believe you were glad we danced no longer; but I would have given worlds—all the worlds one ever has to give—for another half-hour.”

She played” (Jane Austen’s Emma, Ch 28 or 2:10).

In the book we are told the song played was Robin Adair, one of a set of “Irish” melodies which seem to have been sent with the instrument. The word “Irish” in the 18th century also meant Scots.

Robin Adair was written by Caroline Keppel Adair and I have no text in my house so send along what I found online:

What’s this dull town to me?

Robin’s not near;

What was’t I wish’d to see?

What wish’d to hear?

Where all the joy and mirth,

Made this town heav’n on earth,

Oh! they’ve all fled wi’ thee,

Robin Adair.

What made th’ assembly shine?

Robin Adair.

What made the ball so fine?

Robin was there.

And when the play was o’er,

What made my heart so sore?

Oh! it was parting with,

Robin Adair.

But now thou’rt cold to me,

Robin Adair.

And I no more shall see,

Robin Adair.

Yet he I lov’d so well,

Still in my heart shall dwell,

Oh! I can ne’er forget,

Robin Adair.

Welcome on shore again,

Robin Adair!

Welcome once more again,

Robin Adair!

I feel thy trembling hand;

Tears in thy eyelids stand,

To greet thy native land,

Robin Adair!

Long I ne’er saw thee, love,

Robin Adair;

Still I prayed for thee, love,

Robin Adair;

When thou wert far at sea,

Many made love to me,

But still I thought on thee,

Robin Adair!

Come to my heart again,

Robin Adair;

Never to part again,

Robin Adair;

And if thou still art true,

I will be constant too,

And will wed none but you,

Robin Adair!

In context in Austen’s book, the song is moving and ironic. It reveals a deeply trembling vulnerable love on Jane’s part. It also reveals that the two of them find Hartfield (as who would not) insufferably dull, boring, a place where nothing interesting happens, and hardly an intelligent or insightful remark is ever said, no art to be found but what the limited inhabitants themselves provide. We see just how hypocritical all Frank’s praise of Hartfield might possibly be.

*********

Austen’s scene is never chosen as a episode, though in the so-called faithful adaptations so many tiny sentences of Austen’s become episodes and episodes are invented that could have occurred between chapters.

Instead, for example, in the 1972 BBC Emma we get an interpolation of a long poem by Robert Herrick, “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time”, many of its verses read aloud by Mr Elton. In context these verses are ironic and make fun of Emma and Harriet as two virgins who are thus far avoiding the great experience of life (a man’s penis). We later hear that Jane would play “Robin Adair” at Weymouth, but it’s in the context of an intense unexplained dispute between Jane and Frank (Part 4, “Wise Judgment”) where in Miss Bates’s room he again pressures her to play after he has teased her rather meanly by saying aloud that the gift of the piano must come from Mr. Dixon and so too the music found there.

In the 1996 BBC Emmas we get music without words or a conventional classic piece of a slightly later era played before the crowd. The emphasis in the 1996 BBC Emma (written by Andrew Davies) is either on Mr Knightley fighting with Frank Churchill is in effort to protect a strained Jane (two men vying for a woman) or Emma (Kate Beckinsale) playing complacently with Frank Churchill looking on from behind.

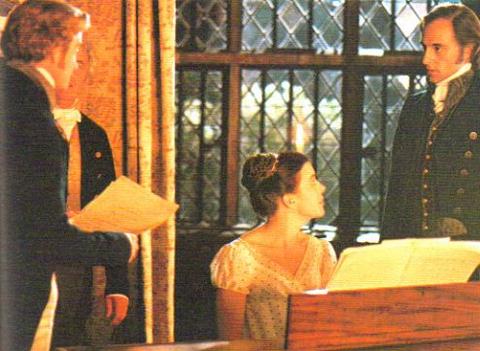

Jane Fairfax (Olivia Williams) caught between Mr Knightley’s protection (Mark Strong) and Frank Churchill’s desire (Raymond Coulthard) (Emma, BBC 1996)

In the 1996 Miramax Emma Jane (Polly Walker) is hardly glimpsed at the piano, the episode between Mr Knightley and Frank Churchill skimmed over so we can dwell on the anorexic Gweneth Paltrow as the idol of the camera in a richly luxurious old-fashioned room:

Emma (Gweneth Paltrow) and Frank Churchill (Ewan McGregor) at Coles’ party (Emma, Miramax 1996)

The 1972 BBC Emma does show us Jane playing at length at Hartfield a few evenings later; she performs before the company a wordless highly sophisticated piece of music:

A backshot of Jane Fairfax (Ania Martin) plays at same Hartfield assembly after dinner (Emma, BBC 1972).

And at the Cole’s Dinner Party Jane does play a melancholy Scotch song. She breaks down and can’t finish it:

Oft in the stilly night,

Ere slumber’s chain has bound me,

Fond mem’ry brings the light

Of other days around me;

The smiles, the tears,

Of childhood’s years,

The words of love then spoken;

The eyes that shone,

Now dimm’d and gone,

The cheerful hearts now broken!

This is a Scotch air by Thomas Moore (1779-1852), from Lalla Rookh, an oriental romance (London: Longman, 1817).

The ‘72 BBC film also insists that Jane’s distress over the insistence she play has another source than her ill health, and provide stills of the very expensive piano in Miss Bates’s meagre lodgings as if to remind us of its enigmatic existence.

Jane Fairfax (Ania Martin) distressed before uncomprehending Miss Bates (Constance Chapman) and Emma (Doran Goodwin), Miss Bates’s lodgings (Emma, BBC 1972)

So the 1972 Emma substitutes Herrick’s poem and invents satiric scenes between Emma and Harriet (Doran Goodwin, Debbie Bowen), with Mr Elton (Timothy Peters) and for the poignant scene uses one stanza of Thomas Moore’s general song of loss. It omits the poignant romance of the Robin Adair scene. The 1996 two Emmas don’t come near to paying attention to Austen’s text.

*********

Lady Caroline Keppel Adair (born 1734, no death date given in any of the sources I could find) was one of large amorphous group of Scots women writers whom Kirsteen McCue in “Women and Song: 1750-1850” writes about in a delightful (and very fat) book I bought myself while researching the life of Anne Halkett, a 17th century Scots and English autobiographer when I discovered it also has long articles on Margaret Oliphant, modern Scots-descended writers (e.g., Alice Munro), memoirists (Elizabeth Grant Smith whose memoirs I read this year—superb and only published unabridged and uncensored in the last 20 years): A History of Scottish Women’s Writing, edd Douglas Gifford and Dorothy McMillan. I recommend the Gifford and McMillan anthology heartily. Also Catherine Kerrigan’s Anthology of Scottish Women Poets.

To return to McCue, using Kerrigan’s anthology, McCue describes the thriving musical Scottish culture from the mid- to later 18th and into the early 19th century. I’ve written some foremother poet postings on some of these women, some of whom also wrote poetry sheerly for reading (Carolina Oliphant Nairne, Anne Lindsay Barnard, Anne Grant, Anne Hunter, Susanna Blamire, Alison Cockburn, Jean Elliot). She names many women and goes more deeply into the lives and music and poetry of a few. She says nothing about Keppel and I couldn’t find her in the ODNB or any database at GMU. Online in a peerage site I discovered she was the daughter of Sir William Anne van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle and Lady Anne Lennox, and married one Robert Adair by whom she had two children. The second was born 1769 so Caroline was alive then.

Songs like “Robin Adair” are often presented as artless, supposedly the simplest expressions of basic human emotions. They do indeed usually present traditional or conventionally-celebrated feelings, but they are usually very artful and most of the time were written by a single educated gentlewoman (often connected to men in the educated classes). We don’t know all the women’s names because it was intensely against the social conventions for a woman to seek public recognition for her writing. There are many nervous-sounding statements by women of the era disclaiming any desire to be thought a learned woman, a reading woman, with lines about the scorn and ridicule heaped on such women and a picture of them which shows the woman herself thought such person rightly a pariah. (It’s not gone from us if you have seen the way the 1995 P&P movie presents Mary Bennet as a flat-chested sour ridiculous young woman. A few have survived which present an alternative view. Thus Joanne Baillie (a known Scots woman poet and dramatist):

I were I were single, I wish I were freed;

I wish I were doited, I wish I were dead,

Or she in the mouls, to dement me nae mairl, lay!

What does it ‘vail to cry hooly and fairly!

Hooly and fairly, hooly and fairly,

Wasting my breath to cry hooly and fairly!

And if you look carefully into the textual history of many of the songs, you find disquieting and ironical reversal statements have often been edited out or reversed.

***********

In Austen’s book we had a simple song from a Scots woman writer, an intensely plangent private moment which is played out in public in a poor lodging room before the unknowing eyes of Emma Woodhouse (and perhaps the more knowing nervous ones of Miss Bates). It’s woman’s romance, about a secret life Jane dares show no one.

I wrote this posting for Wompo because Austen’s text here has been ignored. Most movies are about 70% invention or reinvention on the part of movie-makers. It struck me here is more than an erasure of women’s culture; it’s a reversal of what Austen intended on every level. Jane Fairfax is herself in the novel very thin, has a pulmonary complaint of the family (consumptive), a slightly sickly hue in her complexion (which Frank finds alluring); all but one of the actresses hired to play Jane have been robust. Only Ania Martin is at all thin and granted a contemplative inner life of her own with her music:

I got but one notice on Wompo, from a generous-hearted perceptive woman friend (it’s in the comments).

Austen herself liked to play “Irish” songs on her pianoforte early in the morning before the rest of the family got up. Jane Fairfax is a surrogate for her in the novel.

Miss Sylvia Drake

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- "Ellen your post to the Wompo list is just amazing. I love that Adair poem.

That’s amazing too. But what you write about the 18th c attitudes towards women and then the movie attitudes, well I am impressed by your knowledge but more the WAY you conceptualize. You are a remarkable writer and thinker Ellen.

Also your vacations sound perfect and the way you describe them also inspiring. I will keep your words with me when we go to Maine to a fairly isolated but beautiful cottage by the cold green Atlantic.

Love to you, Ellen,

Patricia"

— Elinor Jul 29, 8:39am # - P.S. The complete song by Moore (sung in the 1972 BBC Emma, Part 3, Episode 5 (Exquisite Performance), runs as follows:

Oft in the stilly night,

Ere slumber’s chain has bound me,

Fond mem’ry brings the light

Of other days around me;

The smiles, the tears,

Of childhood’s years,

The words of love then spoken;

The eyes that shone,

Now dimm’d and gone,

The cheerful hearts now broken!

Refrain:

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere slumber’s chain hath bound me,

Sad mem’ry brings the light

Of other days around me.

When I remember all

The friends, so link’d together,

I’ve seen around me fall,

Like leaves in wintry weather;

I feel like one

Who treads alone

Some banquet-hall deserted,

Whose lights are fled,

Whose garlands dead,

And all, but he, departed!

Refrain

It was set numbers of times; the one Jane plays is not Stephen Foster's though the tune is the same. Jane also sings "boyhood" in lieu of "childhood."

— Elinor Jul 29, 2:47pm # - From John Howell on C18-l:

“Interesting, and thank you. While it could well be that the director or screenplay writer may have deliberately wanted to change the emphasis, it might equally well be something much simpler. Perhaps they could not locate that specific song easily. Or perhaps their actresses could not sing well enough, and Marni Nixon wasn’t available to sing for the lip-synching actress! In any case, I doubt that they would have devoted the screen time to a full performance of all the verses; they never do!

There are similar problems with Shakespeare’s musical references. He never included the music and often not even the lyrics, just a cue to sing such and such a song, and his actors were as often as not expected to provide the songs and settings. Thus a program of “Music from Shakespeare’s Plays” is virtually impossible to reconstruct.

John”

— Elinor Jul 30, 7:33am # - From John Dussinger on C18-l:

“Aside from the omission by all the modern film directors, Ellen, it may be that for Austen’s original audience this ballad of Robin Adair still carried associations with Laetitia Pilkington’s scandalous affinity with this hapless young surgeon—the cause of Matthew Pilkington’s divorce proceedings against his wife after she was found reading a book with Adair late at night in her bedroom.

Such local historical nuances are unlikely to carry over into the glitzy cinematic renderings of Austen’s stories. But for scholars interested in reconstructing the conditions under which the novel Emma was read upon its first appearance, this connection to Pilkington is surely worth consideration. Perhaps this connection has already been noted. I don’t recall it, however.

JD”

— Elinor Jul 30, 7:34am # - From Arthur Weitzman:

“This day may be Austen Sunday. Not only did the Boston Globe devote a whole page to her, the New York Times carried a full page analysis (with graphics) by veteran reviewer Caryn James of the Austen phenomenon this summer. In Boston, her love life (such as it was!) will be on exhibit this Friday in a new film, Becoming Jane. In September the Jane Austen Book Club will debut, and next January 2008 PBS’s Masterpiece Theatre will do a “Complete Jane Austen” with 4 new versions of some of her novels. Jane dominates in ‘07 and ‘08 in the popular culture.

Arthur J. Weitzman”

— Elinor Jul 30, 7:35am # - I thank everyone for their replies. To John Howell, I think the switch is not all that conscious and believe I made a good strong argument for showing that verses by men were preferred and because they present the woman as wanting sex and marriage above all, rather than the romance of sensibility we find in Caroline Keppel’s poem. Beyond that the choice helps to erase women’s culture not only from the later 18th century but again today so that women viewers do not reach what was the real feel of Austen’s woman-centered novels.

To John Dussinger, that’s fascinating. Then “Robin Adair” would be another of these half-hidden sexy innuendo-texts embedded in Emma. We would not get this extra sexualizing but the 18th century reader might have. It’s another text embedded in Emma to add to all those Jill Heydt-Stevenson found in her Unbecoming Conjunctions. Thank you.

Arthur, over the past few days I’ve been getting a high volume of hits on my blog where people are reading the ones about Austen movies and also the occasional critiques of books: anti- as in the Spence and Bottomer one, and pro- as in Auerbach’s In Search of Jane Austen (which I recommend).

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 30, 7:36am # - From Elissa Schiff on Janeites:

“Having just read Ellen’s wonderfully insightful discussion of the Frank C/Jane F/piano gift-Robin Adair poem, I think how it resonates with my earlier impressions of Emma both as a “hymeneal” novel and a novel highly thematically concerned with the welfare and dangers surrounding the state of adult womanhood in British society at the time: at one end of the spectrum, we have Emma in her golden birdcage, who, with the self-knowledge she gains through her immature errors in judgment, will ensconce herself safely once more within the larger domains of Mr. Knightley’s “house”; as if to reinforce this theme [in musical terms of the times it would be played as a series of variations in chords of a connected minor key], her governess, Miss Taylor, now Mrs. Weston, has commenced the action of the novel by marrying and thus safely securing her own future by establishing herself as mistress of a household; Harriet—too stupid to ever be cognitively aware of the dangers she will face should she not marry a kind and financially secure protector—plays out her journey of experience symbolically through the dangerous “gypsy episode” [I had always wondered why JA included this; now I know] and is, fortunately for her, rescued and eventually married off to the reliable and stable Farmer Martin; and even Diana’s favorite, Augusta Hawkins Elton [Diana, if Mrs. Elton is Titania, that would make Mr. Elton Oberon. I don’t think this equation works. Mr. Elton, clearly is meant to be Bottom, the Ass!] is played off as a bit of “comic relief” [on one level—but for her, we must remember, this is a deadly serious matter] paired with Harriet’s husband hunt—Augusta is much smarter than Harriet and realized she had better set herself up with a husband or wind up an impoverished aunt with no power or assets by middle age; finally at the other end of the spectrum, we have the Miss Goddards and then the reduced-in-circumstances Miss Bates as examples of women who have neither inherited meaningful financial security nor married it -ØÞî – and one of these [save for the fortuitous kindness of Mr. K. and Emma] is in near danger of starving. So, Jane Fairfax’s path must be a very cautionary one: She MUST follow Miss Taylor into a “safe” and secure marriage with a Weston-Churchill man or really, she is doomed. I find her plight compelling, am thrilled by her resolve and resourcefullness, and remain just as bewitched as Frank by her charms and talents each time I reread JA’s novel.

Ellen’s discussion of the context of the Robin Adair poem [are we meant, as well to think of the title as “birds in flight” who will escape that birdcage?] that she sings was wonderfully revelatory.

Elissa”

— Elinor Jul 30, 7:40am # - From Betty Rizzo, C18-l:

“This is perfectly fascinating, but there is another pertinent association. I had no idea that Caroline Keppel (daughter of the earl of Albemarle) had written Robin Adair. The surgeon Robert Adair must have been a very attractive person. In 1759 Caroline Keppel came down with a mysterious disease signified by splotches on the face and body, kept her bed, and was assiduously attended by Adair, the family physician. Eventually she simply got up and eloped with him. Robin Adair must have been a love song addressed to him….thus the mention of the song connotes a strong secret passion. Thanks!

Betty Rizzo”

— Elinor Aug 2, 5:26pm # - From Judith Stuart, C18-l:

“ry. As with many old songs, there are at least two versions of Robin Adair,

attributed to Lady Caroline Keppel, available. One of these,

has audiotape for the music and more extensive lyrics; the other I cut and paste

below for those whose browsers dont support all links; its source is

Enjoy! and happy Monday,

Judith”

— Elinor Aug 2, 5:27pm # - Someone on C18-l remarked:

“Robin Adair still carried associations with Laetitia Pilkington’s scandalous affinity with this hapless young surgeon—the cause of Matthew Pilkington’s divorce proceedings against his wife after shewas found reading a book with Adair late at night in her bedroom.’

Nancy Mayer replied:

What year was this? Lady Caroline Keppel married him in 1759 and died in 1769.

Nancy”

— Elinor Aug 2, 5:29pm # - Another qualification, from Betty Rizzo:

“Let me recommend Google Print, to which I was introduced by the master Jim Chevalier a short time ago, as the best reference tool, far better than plain Google. Enter Dr. Adair and Letitia Pilkington, or Dr. Adair and Lady Caroline Keppel, and you find a host of material. (Try permutations, which I didn’t. Robin Adair, Dr. Robert Adair, etc.) The affair with Pilkington was in 1738 and resulted in Letitia P’s divorce. So Adair was considerably older than Lady Caroline. A consideration of the sources on Google Print suggests that Lady Caroline has been said to be the author of Robin Adair, perhaps on the grounds of her determined courtship, but there’s no certainty she was. Apparently Adair was extremely charismatic (and lucky) and a lot of women could have written the song.

Betty Rizzo”

— Elinor Aug 2, 5:31pm # - From C18-l,

“Dear all,

Given the recent thread on ‘Robin Adair,’ I thought this might be of interest to the list.

What follows is a transcription of the title page of William Reeve’s arrangement of the tune (from a copy in the British Library). It includes an interesting and uncharacteristically vehement defense of copyright.

[TITLE] Robin Adair, The much admired Ballad, Sung with enthusiastic applause by Mr. Braham, at the Lyceum Theatre, The Symphony & Accompaniments Composed & Arranged for the Harp, or Piano Forte, By Wm. Reeve. Pr. 1 /6. London: Printed by Button & Whitaker 75 St. Paul’s Church Yard.

Sir,—In Consequence of the very great popularity of the Song “Robin Adair,” now singing with unprecedented applause by Mr. Braham, I am informed that several spurious editions of it are preparing for the Press. Through the medium of your Paper, therefore, I feel it is but an act of justice to inform the Public that the Copyright of the only genuine copy as sung by Mr. Braham, with the Symphony & Accompaniments as composed expressly for that Gentleman by me, has been purchased at a liberal Price by Mess.rs Button & Whitaker, of St. Paul’s Church Yard, & that no other copies are genuine but what are published by those Gentlemen. I am, Sir, Your obedient Servant, [ms signature] W. Reeve. 53, Marchmont St. Dec.r 16th, 1811.

See. “Morning Chronicle” “Courier” & “Star” Dec.r 17th. “Times” Decr. 19th. & “Morning Post” Dec.r 20th 1811.

[end: music follows, Andante Affectuoso]

Cheers,

Leslie

Dr. Leslie Ritchie”

— Elinor Aug 2, 5:34pm # - This is fascinating – I definitely agree that Austen has carefully chosen the song as appropriate to Jane Fairfax’s situation and state of mind at this point, as she wonders if Frank will be “cold” to her or whether their secret engagement will result in marriage. Especially appropriate if it was indeed written by Caroline Keppel to her lover.

It’s a pity the song wasn’t included in any of the movie versions – this all too often seems to be the case with songs or poems featured in classic novels, which disappear from screen versions or are replaced with others which often don’t fit so well.

For me, Ania Martin is by far the best of the screen Jane Fairfaxes -she seems to have the most inner life and to be an alternative heroine in her own right. I always remember the scene where she goes home with a headache after being once again humiliated by Mrs Elton’s attempts at patronising her.

— Judy Aug 5, 12:59pm # - Here is a question I fear only those who’ve seen the 1972 BBC Emma can answer.

Like many readers I’ve talked to, the first time I read Emma I had no idea Frank and Jane were engaged lovers until I got to the point in the novel where Mr Knightley oversees the mean teasing card or alphabet game where Frank pushes before Jane’s eyes (and Mr Knightley’s looking on) the five letters Dixon. Even then I suspected something but couldn’t be sure what.

This make the second and further readings of Emma an exercise in dramatic ironies.

But a movie is usually only seen once, and the dramatic ironies of Frank and Jane’s story are lost the first time round—unless you recognize they are lovers. I’ve read a book on the 1972 Emma where the director and writer said that it was not their intention to try to get an audience to read the book, and that they wanted the audience fully to understand and enjoy the film on its own terms.

To do that, we need really to see about half-way through that Frank and Jane are lovers. As someone who has read the novel before ever hearing of this film (let alone seeing it) I am severely hampered in trying to gauge how much a viewer who had not read the book sees. My guess is from a number of things done explicitly and deliberately by Episode 4 we are supposed to know Jane and Frank are clandestine lovers in this BBC Emma.

Has anyone else seen this film and come to this conclusion?

E.M.

— Elinor Aug 6, 10:57pm # - "Dear Ellen,

Just a quick note – I’ve just written a comment on your fascinating ‘Robin Adair’ blog, but also wanted to add that I’ve noticed (via a spot of googling) that there is an article called (excuse capitals, I’m cutting and pasting!’ ‘’ROBIN ADAIR’ AS A MUSICAL CLUE IN JANE AUSTEN’S EMMA, by PETER F. ALEXANDER’,which was published in Oxford Journals’ ‘Review of English Studies’ in 1988. I couldn’t see any more of the article than the title so didn’t see much point in putting a link to it on your blog, but you might be able to read the whole thing if GMU has a password – here’s a link:

http://res.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/citation/XXXIX/153/84

Judy"

— Elinor Aug 6, 11:14pm # - I too find Ania Martin to be the best Jane Fairfax to date in the movie adaptations. I also think she is helped enormously by an adequate script and intelligent serious production of Emma as a somewhat melodramatic and family-romance drawing room comedy.

I did get hold of the article and read it. Many thanks. Alexander argues that Austen planted the Adair reference twice in the novel, the first time when Jane plays the song and the second when Frank says he knows this song to have been the favorite of the man who gave her the piano. Emma thinks he means Mr Dixon and is distressed at the loudness with which he declares this. On our second reading of the novel, we know he means himself. Alexander also suggests the song reflects some of Frank’s attitudes and anticipates some of the action in the novel to come. He does not try to discover who wrote it or what was its provenance or cultural milieu.

I downloaded and placed it as a file in WWTTA as an article about a song by a Scots woman poet as well as about elements in Austen’s Emma

E.M.

— Elinor Aug 6, 11:29pm #

commenting closed for this article