Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_The Jane Austen Book Club_: A Free Adaptation of all the Austen books! · 22 October 07

Dear Harriet,

I’ve not written to you about any Austen films or books in a while. I’ll make up for that today.

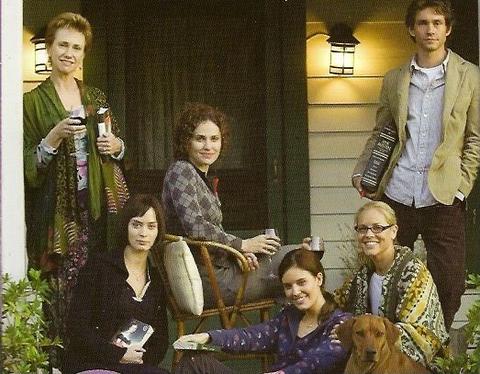

Kathy Baker, Emily Blunt, Amy Brennemann, Maggie Grace, Maria Bello, & Hugh Dancy, committed Jane Austen readers

Yesterday I saw The Jane Austen Book Club for the second time—after reading Karen Joy Fowler’s novel of the same name from which the film was adapted. The book is light easy reading: from its use of metaphor and stereotyped ideas of what young women and men and courtship is like and its thinness of approach to emotional life, I suspect it belongs to the genre of young adult fiction, perhaps series meant for teenage girls. By contrast, Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary is a rewrite and reshaping of satiric columns meant for adult and older women in a popular newspaper and it has more bite (more anger, even if not clearly focused) and emotional depths (even if comic in mood). It has flaws or faults: the narrator who seems so individual and lively is never explained: at first she seems like a character in the book but by the third chapter the book has become told from a not-quite consistent third person omniscient point of view.

One of Fowler’s merits is that she conceived of telling the stories of her six readers as a way of updating Austen’s characters and stories, presenting them as they might appear in 20th century terms. This gives insight into Austen’s books. While I don’t care for Fowler’s need to denigrate Fanny Price as a type, I find her modernization of how she might behave in today’s situations through Prudie apt and insightful. Which gets me to my strange collocation for today: the presentation of Sylvia (the woman whose husband had left her) as a kind of Elinor Dashwood and her daughter, Allegra (lesbian, passionate, wants to pour out her soul) as a kind of Marianne is done in way and in terms that seem to be so close to the way the pair in the 1981 BBC Sense and Sensibility are presented: especially the Marianne character who is wilfull, difficult, vexed and swiftly changing. There’s a paragraph in Fowler’s novel which if you dressed the characters up in 18th century clothes, you’d have outlines for this 1981 enactment.

I’ve seen or noticed this kind of thing before. Some book or film

seems to link to another through Austen or as it were bypassing her and connecting to one another but without having any conscious knowledge of one another. I doubt if Fowler even saw it that she had the 1981 S&S in mind. Austen has provided some stream of imagination that is a connective which these later writers move into.

Now I think some of the interpretations of Austen’s novels out of one another come out of critics doing just what these film and sequel writers do, only not aware that’s what they are doing and using the apparently techniques of objective scholarship. Genre, genre, that’s what makes the difference :) I’m thinking about essays which postulate connections between the novels from Q.D. Leavis’s to Kathryn Sutherland (JA’s Textual Lives).

Again by contrast, Fielding’s plot-design of the Pride and Prejudice story is an imposition on previous matter which only begins in earnest more than half-way through and doesn’t enlighten the reader at all.

So if out of a pop genre, Fowler’s The Jane Austen Book Club is a much better, more clever, less shallow novel than it at first appears. Except for her guying (Fowler writes to sell and knows a vein to appeal to a mass audience through) of the Fanny Price character (apparently a reading girl must not be allowed—shades of Austen’s own Mary Bennet), Fowler shows a large open-mindedness towards interpretations; some of hers are insightful; and her questions at the very back of the book (in the persons of characters) shows she has much irony towards what she writes and has written with an intelligent reader of Austen in mind too.

Just one example: Fowler write: “Austen’s books often leave you wondering whether all of her matches are good ideas;” she cites some unexpected troubling couples (e.g., Louis Musgrove and Captain Benwick, Lydia Bennet and Wickham). Then she asks: “Do any of the matches in The Jane Austen Book Club create disquiet?”

The movie The Jane Austen Book Club, written and directed by Robin Swicord (who did a marvelous Little Women in 1996) improves on the book in some ways. It shortens the stories of the women’s lives; while we lose some of the insight into Austen in the book, the plot-design is kept more surely on the meetings, books by Austen and commentary on how (by reflection) how they can function in real women readers’ lives. Swicord is even more resentful and spiteful towards the serious reading girl, Prudie (whose great happiness at the end is she is now pregnant), but she does manage to make a charming specifically woman’s film and she reflects more briefly how each of the women’s stories is a rewrite of Austen’s own.

Thus I’d call The Jane Austen Book Club a free adaptation of Austen’s novels seen as a group and align it with the other Austen films I’ve been studying. Jocelyn (Maria Bellow as a woman who is a strong type and has chosen to live alone) is a recreation of Austen’s Emma; Sylvia and Allegra (Amy Brennemann and Maggie Grace, a loving mother and lesbian athletic daring daughter) of Austen’s Elinor and Marianne Dashwood; Prudie (Emily Blunt), Fanny Price (her story contains a play within a play); Bernadette (Kathy Baker), Elizabeth Bennet; Grigg (Hugh Dancy), a very appealing Henry Tilney, Mr Knightley and sweet Frank Churchill all rolled into one (while I regard Frank Churchill in Austen as a callous cruel cad, I do love Henry Tilney and Mr Knightley as an older Mr Darcy with impulses that remind me of William Cowper). Some of the minor characters recreate major and secondary characters in Austen. Sylvia’s husband, Daniel (Jimmy Smits) is Wentworth, Grigg’s sister, Lynn (Myndy Crist), Eleanor Tilney. In the book in passing there are characters who don’t appear at all in the movie and in passing combine characteristics of different of Austen’s heroes and heroines (for example, a perceptive portrait of a Jane Bennet type—someone who needs to see the world as better than she knows it is), and more troubling (as Fowler would name this probably) characters, e.g., Mr Bennet.

This is not to say all the characters connect: Prudie’s mother (played by Lynn Redgrave) is an original creation which is self-reflexive: she has survived by pretending good and happy things are happening to her and have happened, when no such thing. At some time in the past life taught her not even to dare try for them. Prudie, her daughter, mistakenly blames her. I did love how she openly accused her husband of flirting with a girl who had big breasts and dressed like an ostentatious vulgar ornament; how many times I’ve been appalled by realizing men I respected go for that sort of woman when it comes to a partner for life. The film functions as a release for women in other ways too.

Swicord’s film also (like the other Austen films) shares a number of characteristics seen in women’s films: the community of women, a certain friendly (for lack of a better term) tone, which can move from witty and satiric (Bridget Jones’s Diary and Clueless are variants) and speaks directly to the audience (Julie Delpy’s Two Days in Paris), to high romance (You’ve Got Mail). Some of the scenes reminded me of scenes in Friends with Money and Lovely and Amazing. Several of the producers were women. It’s not a great film: to my mind it misrepresents Austen’s books by not presenting them as hard and satiric but sweet and pleasurable, and in its plot-design which is based on the idea that love (and marriage or having a partner) is the be-all and end of all woman’s happiness.

But like other films of the free adaptation variety (the end of the film follows Persuasion in the way Bridget Jones, the Edge of Reason does), if you don’t ask that the film reflect Austen’s books or deal more than superficially with the serious issues it does bring up (for example, how an older man can easily get away with and many do leave an aging wife for a younger woman), but rather an idea about Austen’s books that functions among a wide swath of people who read them, it’s charming and intriguing and often moving. I admit it brought tears to my eyes several times. The good-natured jokes about the Austen addiction made me laugh, as well as what I’ll call in-jokes about obsessions in Austen’s own novels. The book gave some of the more unusual interpretative lines to Grigg: not all of these survived into the movie, but this one did: “One thing I notice about Emma is that there’s a sense of menace … (p. 15, with a catalogue of incidents). I just loved how he went out and read the whole of The Mysteries of Udolpho during the Northanger Abbey month. So there Andrew Davies! Swicord also brings out how talking about books brings out how people read them with their intimate lives in mind and so if you carry on for any length, will soon lead to tension and sharp dissensions.

I wanted to write about the book and film as much for how it has been reacted to in public too. Early on Caroline sent me an intelligent review,

“A Film to curl up with”, mild praise by Ann Hornaday in the Washington Post online. If you can’t reach this one, here’s a snippet:

“A predilection for Austen is helpful but not required to enjoy a movie that derives as much observant humor from the indignities of modern life (which are wittily retailed in the opening montage) as from Austen’s own densely layered texts. And like Austen herself, screenwriter Robin Swicord, who makes a promising directorial debut here, is all about subtext. ”

Yet it has apparently been a box-office flop. It was released in a few movie theatres in the hopes of garnering popularity through word-of-mouth. This was the method of the 1995 Miramax Sense and Sensibility. So it was playing nowhere I could get to until Jim and I went to Chicago and he went with me. I doubt he’s read any of the Austen books, and he found the movie very funny. There were but 4 men in the audience that was itself very small. The theatre was almost empty. Our art cinema began JA Book Club in Theatre One (its biggest) but soon demoted it to Theatre Six (its smallest). Cinemart is now the only local theatre in all my area (DC, Northern Va, southern Maryland) screening the film. And the room was packed. All but one person in that audience were women. The proprietor had announced he would alternate the movie with another (what he does for a failing one), but instead it was playing all day. I overheard one fretful woman tell another she really doesn’t go to “chick-flicks”. During the movie the laughter was often of the slapstick variety (there are elements in the film which invite this) or laughing at someone (meanly), but it was also about other things, and the audience appeared to enjoy the movie very much.

I’d like to say how strong is the fear of ridicule. Calling a film a “chick-flick” was a barrier; it is based on a genre much-despised, the Austen sequel (this is ironic for its content and status was what led to its being made into a movie and selling widely). (For my part I would label many popular action-adventure, science fiction, western, & thriller films “dick- or prick-films.” Just like there are endless silly men’s novels.) However, the mostly maudlin, often misogynistic at the end outright imbecilic Becoming Jane (also a free adaptation of Pride and Prejudice combined with bogus ideas about Austen’s biography) was an unexpected hit in this theatre. It filled Theatre One for weeks. You may say “bio-pics” are liked; I wonder.

Still since the audience for Becoming Jane seemed to have many males in it (I suppose it wasn’t a chick-flick because it had a sentimental effeminate macho male at the center and presented cruel and stupid pictures of women), and this one for The Jane Austen Book Club but one, I write this to urge other women not to be so intimidated. It’s one thing to conform in the most serious issues of your life (including your very eating habits), lest you be somehow punished or seen as a feminist (horrors!). It’s another to deprive yourself of real pleasure.

To quote Hornaday on the film again: “with its literate merging of good sense and passionate sensibility, The Jane Austen Book club possesses all the pleasures of a guilty pleasure, just none of the guilt.”

And the book is worth a contemplative (if rapid) perusal.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- When I put some of this blog on WWTTA, Judy replied:

“I think I might have already mentioned that I quite enjoyed reading ‘The Jane Austen Book Club’, but more for the wit and intelligence of the writer than for the characters, who I quickly forgot. Like Ellen, I was also frustrated that we never found out who the narrator was. I’m looking forward to seeing the movie when it is released in the UK.

I hadn’t noticed all the parallels between the characters and Austen’s heroines, and will look out for these when I see the movie – then maybe take a look back at the book again.:)

Judy”

— Elinor Oct 22, 12:34pm # - When I put it on Janeties, Nancy M replied with a negative review where the criteria was faithfulness to Austen herself. It’s revealing that the writer is someone writing for “Teen Screens.” Fowler is a writer for teens:

“TYLER PROW

We love Jane Austen. Her stories seem real, even with the fairy-tale endings. When you see a movie based on an Austen novel, you already know the plot, the characters and their situations, and you probably have seen another version of the same movie. Nonetheless, it draws you in,and you cheer for the heroine and squirm in your seat during the proposal.

Since we like all of Austen’s stories, surely we would like to see all of them at the same time. At least, that is the idea behind “The Jane Austen Book Club,” a modern-day incorporation of all six of her finished novels. But it’s no Austen, and, therefore, it’s a disappointment.

All the problems are due to the script. It’s full of trite lines, such as, “He looks at me like I’m the spoon, and he’s the dish of ice cream.” Though the amazingly talented Emily Blunt says this line, I couldn’t help but laugh aloud … after my eye twitched.

The life of each character in the book club reflects the plot of one ofAusten’s novels. That might have worked if screenwriter/director Robin Swicord hadn’t played favorites. She obviously prefers the “Emma” story and spends most of her time on it. She does not even have a “Pride and Prejudice” subplot. Only the “Sense and Sensibility” and “Persuasion”

vignettes are balanced and well-developed.

The best thing about this movie is its cast. Blunt, whom you’ll remember as the acid-tongued British assistant in “The Devil Wears Prada,” is fabulous. Every character she plays is wonderfully dashed with a bit of eccentricity; here she’s Prudie, a high school French teacher who has never been to France and has a crush on one of her students.

Kathy Baker is wonderful to watch as an Earth-mother type. Amy Brenneman is her usual clumsy, tense, charming self. She plays the same character in everything she does, but it is very entertaining to watch. The other performances were fine, though certainly not as noteworthy.

Overall, “The Jane Austen Book Club” is not a real Austen movie, nor is it the cute, original romantic comedy the commercials make it out to be. It feels unauthentic and coquettish. Were it not for the actors, it would have been a very painful hour and forty-five minutes. Your best

bet is to wait until it arrives on DVD.”

— Elinor Oct 22, 12:37pm # - While I did enjoy the movie, I want thank Nancy for posting the review by Tyler Prow. I agree with parts of it, and could go farther in the same direction.

The movie did irritate me with its coquettishness, and the way love was presented (as I wrote be-all and end-all to the point where getting pregnant will solve all your unhappinesses is seen in the last still). I particularly disliked the presentation of Prudie who is left married to a man clearly unsuited for her: she alone argues rather seriously a couple of times about the book; in another review of the movie I saw her called “a prig.”

It’s nowhere near as good as any of the work of Nicole Holofcener and when (I think I said) I thought really Bridget Jones’s Diary was in some ways better that could be read as a condemnation— only that I did enjoy the book, BJD. On the other hand, it resembles Holofcener’s films in revealing ways, and will put before you a popular image of Austen whether those who read her (and not the sequels) like it or not.

Take away the criteria for faithfulness, and understood how fierce has been the attack on any feminism, and you see the movie is brave in its way. Also the book does develop all the Austen novels equally.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 22, 12:40pm # - I liked the beginning of the book, thought the rest of it was tiresomely obvious.

— bob Oct 22, 12:50pm # - Well you were wrong. I’m not surprized its issues, content, wit, characters (&c&c) were not of interest to you though.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 22, 2:40pm # - Why are you not surprised? Am I such a limited person, in your estimation?

— bob Oct 22, 9:38pm # - About women’s art and issues, yes. You consistently have a masculinist point of view.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 22, 9:43pm # - Wait a minute. I realize it was rude of me to write so dismissively of a book you said you liked. I could’ve kept silent, or phrased my disagreement more courteously. In truth, I was disappointed you liked it, because I respect your point of view.

— bob Oct 22, 9:47pm # - You’re just saying I have a masculinist point of view. I don’t. It’s true I don’t share your particular perspective, but a number of well-known feminists who are friends of mine think I’m not especially backward. Isn’t it really the case that it’s hard for you to be disagreed with, unless it’s done very respectfully, and that I don’t always keep that in mind?

— bob Oct 22, 10:41pm # - To Bob, I’m trying not to insult you. I could've instanced comments over the years (or behaviors) on list which seem to me treat women as sex objects and are masculinist in other ways. I could use other words to describe your tone to me which would also be evidence of my point of view here. The book and film are very much women-centered books with a woman’s point of view in them—of sex for example. I don’t think the book is even 1st rate, much less a fine book. I said that. But it is full of interest for women readers -- and that's why it's a best-seller; that's why the few theatres playing it now are filled with women viewers even if they are feeling shamed and ridiculed. When you say you have quite a number of women friends who are feminists, it reminds me of people accused of anti-semitism who say they have lots of friends who are Jews. And then there's the typical male dismissal of what is important to women: "Women's talk is so tiresome, they make such mountains out of the obvious and molehills."

You’re responding to me by impugning my motives for telling you what I did. My character. I agree I’ve impugned yours if you think to yourself you actually look upon women as creatures equal to yourself and make this part of your self-esteem. It's quite true I like people to treat me (and others) with respect. Why should I take discourtesy? Is that your male perogative coming out? Jim tells me women don't go into IT because it's right now dominated by men just about wholly and they refuse to treat one another any other way but roughly and make coarse jokes (the type we sometimes see on C18-l -- and recently there was a tiny recurrence which you contributed to). You're disappointed in me? If that's not faux prissy & also condescending, I don't know what is.

You need not respond to this blog nor read it. I'd say you have this tendency to badger people. On lists you will persist in some point of view over and over again, and then bother whoever it is you are talking to on list ceaselessly until you get them to acknowledge your point of view or both you and your target tire of it; sometimes the listowner or others on the list manage to pressure you to stop (or puts you on moderation). I have a rule on my three lists that no one is to badger anyone else. That's what you are now doing here. You are beginning to behave just the way you do on lists. Keeping up a topic or point of view doggedly, tenaciously, and when you don't like what is said ratcheting up the rhetoric: only here you have no audience or at most a very few. I ask you to stop it here or you will no longer be able to post on this blog.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 23, 6:14am # - From Penny:

“I still have not seen The Jane Austen book Club. It does not seem to be playing in many theaters and seems to be playing in not so easy to get to places. It seems only the male fantasy movies are making money.

Penny”

— Elinor Oct 23, 6:26am # - Dear Penny,

Your comment has set me wondering.

On Janeites, Nancy Mayer queried thus: "Someone in Atlanta went to see this last Sunday but when he arrived at the theater, he learned all the showings had been cancelled. Has any one heard anything about a curtailed showing?"

I had assumed that the film was leaving the theatres so quickly because no one was showing up. I assumed it played only at a few theatres because that was a strategy for disseminating it—one used for “minority” taste films. Women tastes are treated as a minority taste.

However, now I’m thinking of what happened to the latest Jane Campion movie. It was harshly castigated, ridiculed to the hilt, and disappeared before the first weekend was over. The Cinemart art theatre I go to is an independent one and the owner often does try to keep going by showing a film he has a hunch really has an audience and is screening nowhere else. Often they are women’s films (one was Ladies in Lavender), very artful European ones with socialist sympathies (Goodbye, Lenin).

So perhaps the repression is of the type Susan Faludi described in her Backlash. She shows how the effect of anti-feminist and anti-woman-centered points of view feels like a conspiracy simply because those in charge (men and complicit women on behalf of macho male competitive and other norms) keep it reinforced. In this they supported by people with access to important spots in the press (often men) who say how tireseome and poor and thin this one is, a chick-flick, or (my favorite this) not balanced :).

Good to hear from you,

Ellen

— Elinor Oct 23, 6:40am # - From Diana B,

“Dear Ellen,

I enjoyed the movie, though not enough to see it for a second time; the book I could barely bear at all. For me it was about as highly overrated as a book could possibly be. I daresay that re-reading it after seeing the movie will make more things come out in it …”

To which I replied:

Perhaps I was in the mood for it; I cried at moments during that movie. It seemed to hit something in me. And I am a Jane Austen book lover.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 24, 6:49am # - From Diana:

“Last word on The Jane Austen Book Club was from my friend Denise in Alaska/East Hampton. She’s not a writer, she’s an artist, but her comment amused me:

‘We saw the Jane Austen Book Club movie. I thought of you, before I saw it so I thought maybe it would be fun, but sorry to say it was SO California and reminded me of that other chick-flick Friends with Money... maybe just maybe if one were already a Jane Austen fan, which I am not (just not my thing but I like the costume drama and language/”manners”) maybe it would seem relevant, but somehow it just wasn’t strong enough.'"

To which I again replied:

But I loved Friends with Money! Yes it’s a woman’s film and I like women’s films the way I like women’s novels. I agree with your friend that the movie just wasn’t strong enough (and the book was too thin about emotions). The film-maker and screenplay writer mostly touched on issues, dramatized them lightly and then provided faux happy endings. However, they did at least present them, and now I think of it in the case of the Fanny Price character (this is interesting to me), the presentation was strong.

In Fowler’s book (as I say) she has a list of questions at the back which are intended to suggest to the more perceptive thoughtful reader that she did not present reality truthfully, and if you think about her pairings and what happened more deeply, you will see there is much to find disquieting and troubling. Especially probably the older man who leaves his wife and could so easily get away with it.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 24, 6:54am # - From Austen-l, Edith Lank:

“My review: the book was okay, really more a collection of short stories than a novel, I thought. The movie was better than the book. Not a great movie, but a good one.—Edith”

— Elinor Oct 24, 8:20am # - Dear Edith,

Thank you for your comment.

I thought the movie improved on the book by presenting the stories far more concisely and genuinely structuring the story around the monthly meetings. Sometimes the book seemed to forget about the monthly meetings and talk about Jane Austen while the author worked out the story line of a particular character’s life to make it reflect or be a rewriting of one of Austen’s heroines or heroes. It was a group of short stories interwoven—each linked to one (or more) of Austen’s novels.

But as is common a novel can give a different kind of depth or strength or self-reflexivity a film can’t because it is verbal, and so on that score, the book is more satisfying.

I thought to myself, what if there had been a book for Nicole Holofcener’s Friends with Money. I imagined it might bear a considerable similarity to The Jane Austen Book Club.

Ellen

— Elinor Oct 24, 8:24am # - From Christ on Austen-l:

“When I read Fowler’s JABC, I had a little trouble accepting the rotating narrator, if that’s what it was. Did anyone else?

Also, the real book, or subtext, seems to be about adolescent sexual awakening of the various characters vis a vis their sketches of youth, which I suppose can be related to Austen novels, if you want it to be. But no one that I can recall mentions this—not even the original book reviewers.

I had the feeling after seeing the trailer (and all the young actors) that the film is more engaging, especially for youth.

Unfortunately, it did not stay long enough in the theaters around me to be able to see it—even though the author lives in town.

Chris”

— Elinor Oct 25, 7:22am # - In response to Chris,

I thought the book was somewhat careless, and that the individual narrator (who seemed to have a personality of her own) would emerge as one of the women, but by the 3rd chapter the narrator had faded into an unexplained lively omniscient narrator who we could identify with the author at times.

I don’t know what you mean by the real book as I thought the stories were from the get-go invented to be rewrites of the Austen ones. I agree that sexual awakening is part of several of the incidents and story parts (the stories have different turns and incidents in them), but then some of Austen’s stories can be regarded as about sexual awakening: Marianne Dashwood’s story (a comic or happy ending rendition of Eliza Williams), in a way Elizabeth Bennet’s (she does not recognize her antagonism to be a form of attraction), clearly Emma Woodhouse’s.

But then again not all. Fanny Price knows she is passionately in love with Edmund and must hide this; Anne Eliot’s awakening was cruelly cut off. And so the stories in the book are not all about sexual awakening: Sylvia’s husband leaves her and his story is turned into a Persuasion when he returns for a second chance, and even writes a letter. NA is about gothicism in the movie, and I was glad to see Fowler defending Radcliffe by having her hero like Udolpho (as people will see in his 2007 NA Davies trashes Udolpho to the point it’s burned and replaces the sexually titillating Monk as Catherine’s reading).

I’m not surprized sexual awakening was not discussed. The film was dissed, and the content not taken seriously the way women’s content in women’s movies often is not. But then it must be said most popular reviews don’t go into content in detail and often trivialize what is shown. Movies enable people to see before them what is usually not discussed and is important and what allows this to go forth is the very silence about the content—people begin to talk only when something strongly taboo is broken.

Isn’t it curious how Austen’s books are being turned into teenage films? Clueless. JA Book Club does read like a teenage book (compare it to Bridget Jones’s Diary which was originally satiric columns in a newspaper for somewhat older women). This is trivializing I think. The audience the two days I saw the film was not made of young teenage girls. There were women of all ages, but the predominence seemed slightly older women. And the stories most made something of—Jocelyn’s an older woman who chose not to marry until she slowly falls in love with Grigg, a much younger man; Sylvia’s of an older woman left by her husband for a somewhat younger woman, and her relationship with her daughter, Allegra (a rewrite of Mrs Dashwood and her daughters) is not teen stuff. These reflect older women’s problems.

I did think it interesting how the strongest stuff in the movie was the Fanny Price story, and Emily Blunt as Prudie had th most memorable scenes. A vindication of the strong material that is Mansfield Park.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 25, 8:53am # - From Lesley P on C18-l:

“I too was disappointed by the book. I was even tempted at times to wonder whether it was using Austen as a lens through which to understand our world in some useful ways, or using our world as a lens through which to understand Austen in some useful ways, or simply capitalizing on Austen’s popularity in our world in order to sell an OK but not earthshakingly brilliant book. I’m not sure that last is fair, but I was sometimes tempted to think it.

Lesley”

— Elinor Oct 26, 7:54am # - I wrote to Diana B as follows:

"I really was dismayed to see how the audiences for JA Book Club were kept small by fear of ridicule: I really think the movie didn’t do as well because it was tarred as a sequel. We are having a small stunning event in my area as the one theatre with JA Book Club is jammed packed with women in the small room it’s playing all day and night. Women could buy the book and read: no one could see them and they need not be embarrassed. Do a sequel and it’s possible you can get in print; do one which somehow hits the modern sensibility (though I think that too positive a word for pop culture) and you can get it into a movie, but at the same time if the word “sequel” gets too close, people jump away. The Tamil S&S only put its status as a sequel on the cover of the DVD when it was discovered the DVD would really sell much more widely if I have found it was known to be an adaptation of S&S.”

And she wisely replied:

“Yes – both The Jane Austen Book Club and Becoming Jane have completely tanked. Indie movies in general are doing poorly now, due to the new technology; people aren’t paying $10 to go see indies when they’ve got systems at home. The market was certainly hurt by two JA movies being out at once, and neither proved to be a breakout hit, for fairly obvious reasons (though both will do well on DVD). Becoming Jane wasn’t a lavish feelgood costume romance, it was dark and problematical; and The Jane Austen Book Club was a summer movie marketed at exactly the wrong time of year. It wasn’t that people were “ashamed” to see a sequel, sorry but I think that’s nonsense (!). The general moviegoing public doesn’t know JA sequels exist, much less that it’s somehow shameful to see them. Book Club sounded unexciting and unappealing to movie audiences, and women certainly couldn’t get men to see such a thing. It didn’t break out of its older middle aged woman stereotype. It seemed like something nobody but a myopic librarian would want to see, and even though it was in fact decently done, the marketing and the reviews didn’t appeal to younger people. Nothing to do with stigmas. Markets!”

— Elinor Oct 28, 6:26am # - To which I responded again:

“Thank you very much for your candor. My explanation for the unusual phenomena going on in the small room in my local “art” cinema may be partial and too narrow, but I think there is something going on interesting which needs some explanation.

You say Becoming Jane tanked; not altogether in this theater: it filled the large room for three weeks and then no one came. I should have said this theatre has a Jewish population (there’s a community center nearby and this theatre will do festivals of Jewish films for them) and American middle class Jews are still Anglophilic: it’s a class or status aspiration. And yes in the JA Book Club crowds there are mostly middle aged or at least mature women.

You think it was the timing that ruined JA Book Club. I do think reviews count and they ridiculed the movie as a “chick-flick.” But I’d agree that this would a minority reaction, for how many people read reviews? It disappeared so quickly too in a number of areas too—like the Jane Campion movie. Still, I don’t know how one can label a movie as “summer” when it comes out in October and is not at all about summery or holiday things.

Certainly very few men went. (It's to Jim's credit he did and enjoyed the movie.) If nothing else, this is to my mind the visible and outward sign of what ultimately killed the film is men don't want women reading. The prejudice against librarians has its origin in this. Women must be ready to open their legs to men and have endless babies and nail themselves to these babies or they are not "real". The "darkness" of Becoming Jane and presenting her as Bette Davis in Now Voyageur, pitiful spinster, at the close of the film is telling.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 28, 6:30am # - Diana in reply:

“Well, Jane Austen Book Club tanked a lot worse than Becoming Jane; $3 million gross so far, as compared with $18 million which isn’t that horrible for an independent. Timing does count. This isn’t my theory, it’s a whole science, you wouldn’t believe how much work is done and how much money spent by people in the industry scientifically studying these things. Timing, and word of mouth (which is affected by reviews) is all critical. Advertising too and placement and a million other things.

D.”

— Elinor Oct 30, 4:46pm # - I asked Diana what is the criteria for a summer movie, and she responded:

“A summer movie? Women’s chick-lit movies of the light variety are generally seen as performing better if they open in summer – Fried Green Tomatoes would be the perfect example. They try to release different types of movies at different times of year. Serious artistic movies are often released in December so as to qualify for Oscars.

D.”

To which I replied:

How about this idea: the explanations given for the commercial failure of JABookClub (and many have been given since a lot of women who went liked it) are tea-leaf reading. Movies which are not expected to succeed sometimes do, and wildly; movies expected to succeed flop. This happens all the time. If there were a science of predicting, the industry would never have a failure and endlessly make huge sums. But they often fail. It’s like political elections. People endlessly talk of why this candidate is succeeding or that failing. It’s usually hindsight talk. The people who vote don’t tell their real motives or thinking (which is often embarrassingly stupid or prejudiced). The only real explanation that is really true is so-and-so won because he or she got the most votes according to the particular system of counting.

The movie industry doesn’t care why a movie fails, only whether it does ot not, that is, the bottom line; and then they invent by hindsight.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 31, 7:18am # - From Sheldon G. on Victoria:

“Since we’re talking of films now, especially films based on Emma, I thought I’d mention this year’s Jane Austen Book Club, in which modern-day relationships parallel the ones in Jane Austen’s novels.

There’s an especially interesting echo of the Emma-Mr. Knightley-Harriet triangle, but all the Austen novels are at least mentioned, with a lot of emphasis on Persuasion.”

— Elinor Nov 1, 8:49pm # - I wrote:

“Thinking about the way the characters in the book and movie respond to Austen, I offer the idea The JA Book Club is different from most of the “Austen” movies in that it does not Victorianize Austen. I’d say most of them do: the exceptions are apparently in the free adaptations (e.g., Clueless, Metropolitan which also feature teenagers as well as people in their very young twenties). It’s been suggested the bow-and-arrow scene in the 1996 Miramax Emma is Victorian; however, the scene is a direct take-over of a scene in thr 1940 MGM P&P (with Greer Garson hitting the bulls-eye and impressing Laurence Olivier). Now the 1940 MGM film is influenced by film adaptations of Dickens, the characters made into very sweet people and dressed in costumes reminiscent of illustrations of Victorian novels from the 1830s. But I’d say that the emotionalisms, investment in marriage and family, the presentation of masculinities (especially since the 1990s films), and motifs for the women (such as the opening framing device for the 1995 A&E P&P) represent how people see Victorianism positively nowadays.

One example: Had Jane Austen ever included a celebratory Christmas in any of her novels (she only has Christmas there in fragments and as celebrated in the 18th century—not a family affair necessarily at all), this would by this time have become a central event in these films. Alas (I use the word ironically), she did not. However, if you look at the free adaptations though you find Christmas is creeping in as part of the joyous climax to the film where hero and heroine at long last get together surrounded by family and friends (Metropolitan, Bridget Jones’s Diary—in the second the final scene is in the snow; in the first there’s a climax in a big church in NYC with the Fanny Price character in tears). Finally, returning to the 1940 P&P it’s no coincidence that the man who played Mr Bennet, Edmund Gwenn, played the part of Chris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street. The 1940 film’s conception of Austen’s novels is still influential for its way of regarding the novels as benevolent comedy is part of the backdrop to the 1995 A&E P&P, and it’s final lines of the father saying Mrs Bennet can send in men for the other daughters goes back to Milne’s Miss Elizabeth Bennet and as an ending is repeated in the 1979 BBC P&P and the 2005 Universal P&P.

How students “read” Austen is centrally influenced by these movies—and us too (if we admit it). There have been articles in the film studies literature of the films to show this.

E.M.

— Elinor Nov 1, 8:51pm #

commenting closed for this article