Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_Persuasion_ 2007 & the latest Austen films · 1 February 08

Dear Harriet,

I want to link in two remarkable reviews of the 2007 Persuasion (directed by Alan Shergold, screenplay Simon Burke), one at Alice’s Journal, Living in the Past, and the other by Paul Mavis, at DVD Talk. I’ve twice tried to do justice to this film (The Compleat Persuasion and Sister Novels, but not Sister Films: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion), and included stills from its version of the country walk (3 Persuasions), but know I have not begun to do justice to it, partly because I’ve not watched it as often as I have the 2007 Northanger Abbey (directed by Jon Jones, screenplay Andrew Davies) probably because I’ve tried to stick to my scheme of studying the apparently faithful adaptations first.

My sense was the 2007 Persuasion is a filmic development out of elements in the 1995 Persuasion so that in Paul Mavis’s words the “barely-submerged romantic hysteria that suffuses Austen’s work” which is interwoven with other elements in the 1995 film become dominant in the 2007 one. In Alice’s Journal, Judy concentrated on the ending scenes (which have been mocked) to show that Anne’s “hurtling” through Bath streets is an beautifully realized dream sequence ending to a film about wild emotions barely kept in check for the principals to remain sane;

then time is slowed down at the close for the agon of the relief of at last retrieving the precious relationship. Paul Mavis’s analysis of the aesthetics and techniques of the work gives us the close reading one seeks as proof of such a hypthesis. Mavis articulates a central point: Persuasion is quite adept at getting across the barely-submerged romantic hysteria that suffuses Austen’s work He hits the striking innovations: the way the actors look right out at the viewer (Anne at the end after the kiss and before the scene at Kellynch does this); the music and colors. I quote some of his sentences:

“This new version of Persuasion condenses events and eliminates characters in an effort to emphasize the raw emotions that fuel the much more dense novel upon which it is based …

”[This] Persuasion is quite adept at getting across the barely-submerged romantic hysteria that suffuses Austen’s work, by concentrating the complicated plot into a series of thwarted romantic encounters, heightened by the director’s more modern, subjective filmic treatment. Actors in [this] Persuasion look right at you; they’re not afraid to peer into the camera directly, to bring the viewer into the emotion being portrayed on the screen.

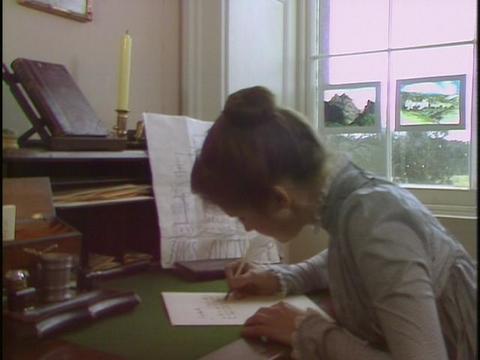

Anne Elliot (Sally Hawkins) writing, her face twisted with grief, aware the audience is looking at her

“Director Shergold tries other camera and editing techniques to give Persuasion a more immediate, charged feel, including lots of peripatetic, hand-held camera movements, intense, almost too-near close-ups (the final kiss between Anne and Frederick is a marvelously excruciating, weirdly fervid kiss of equal parts sublimation and hesitancy), and lightning-fast editing schemes (the final hysterical flight by Anne as she tries to find Frederick is a standout) that mark Persuasion as a most un-Masterpiece Theatre-looking film (even though ironically, Persuasion premiered on the venerable PBS series). Some viewers, trained and comfortable with the more staid, sedate, measured pace and tone of previous classic novel adaptations of this sort may feel a bit lost with Persuasion, but I found it an invigorating experience, boiling the essence of Austen’s almost-doomed romanticism down to a passionate, roiling, emotional fever dream beneath the outwardly cool, detached, rigidly locked-down characters …”

“Also notable is the glorious production design by David Roger and the dark, naturally lit cinematography of David Odd. Shot at times with what looks to be natural sunlight or candles, there’s a dazzling steel-grey, icy beauty to Persuasion that perfectly matches the repressed, thwarted emotions of the lead characters

....

I rejoice to link in these two reviews since in many places I’ve been online this film either gets trashed or is spoken of at best with mild praise. So it’s good to see someone validate my view it is a piece of brilliant film-making. I’d also like to add two new lines of argument to those I’ve put on this blog already.

1) As a group these minimalist Austen films (the MP, NA, and Persuasion) speak to a new generation and the 2007 Persuasion in particular reminds me of the 2005 P&P and also Atonement (same director, same lead actress as the 2005 P&P). They present a view of love and romance that is disquieting, but is one that is shouted from the rooftops of our culture at this moment. Yvette is a lover of Austen and she just loved the 2005 film, this Persuasion (though she likes equally the 1995 one) and also Atonement. She burst into tears at the close of Atonement the way she did at this Persuasion. She saw nothing wrong in that last scene by Kellynch. Stars are chosen for psychological type and baggage and Keira Knightley is a icon that (alas) embodies something I heard described in a talk on Austen and post-feminism. This notion of love as a refuge, total refuge, and Austen as providing books which envision this.

Myself I don’t think it’s dissed because it’s not of the literally faithful type, but that it’s not being literally faithful makes attacking it easy. I think it’s partly that the heroine is abject, but since when I brought that up on Austen-l and Janeites, I was ignored or contradicted, I have no evidence. Had I complained the heroine was weak and used words like those of Fanny Price, I might have gotten some agreement. I feel the viewers are embarrassed by it; the film-makers took a risk in breaking a taboo against showing intense emotions, depression, and then there’s this long tradition starting with the 1940 P&P in films and much earlier in books of talking about Austen as if she were simply comic and complacent.

If there is something to criticize—and there is—it’s the abjection embodied in Sally Hawkins’s stance. In the screenplay and direction of this film, Sally Hawkins was continually made into a femme abject extraordinaire. She is not gently encouraged to get into the carriage with the Crofts; Wentworth lifts her into it like a doll. This Anne Elliot is in imminent danger of a nervous breakdown; she is just in an utterly shattered state from beginning to near end. For any woman who fancies herself the slightest feminist to see the heroine blindfolded at the end is astonishing. Talk about put your faith in your husband. What he says goes, where he wants to go and so on. Davies’s Catherine Morland never has a subversive thought and is over-the-top remorseful for having genuine insights into real crimes of the heart; Maggie Wadey’s Fanny Price ends in an ecstacy in a wedding dance where (recalling Keira Knightley in the 2005 P&P) the bliss of being a Mrs (this time Bertram) will it’s assumed just go on forever.

Interestingly though, the males are presented analogously. Wentworth was presented as still deeply in love with Anne throughout; unlike Austen’s Wentworth and Dear’s, he does not need to relearn love; he is aching with the same grief and loss as Anne. At the end his joy is as deep as hers:

Frederick Wentworth (Rupert Penry-Jones) gazes back at Anne

Andrew Davies’s Henry Tilner (played wonderfully by J.J. Feilds) is another one of the world’s walking wounded.

Henry Tilney (J. J. Feilds) shakes with joy at Catherine Morland’s (Felicity Jones) yes

It was the irretrievableness of the loss in Atonement that so hurt, and the scene where the dream vision of what the couple could have had not just the woman had they not died (as Harville’s Phoebe does in Austen’s book) was where the breaking point comes.

Over on Austen-l I argued the 2007 Persuasion does take off from a core meaning in Austen’s book—in the way the other analogous or intermediate adaptations do. It is a movie about love, only the way love is dramatized is dark. It reminds me of what Fay Weldon said in an essay where she discussed Austen: she argued that the idea love is an intense single-commitment is dangerous, and that she presented Austen’s Elizabeth as also capable of and really loving for a little while Wickham, and then being very interested in Fitzwilliam and hurt when he so swiftly rejected her; Darcy came in third in the film. The film-makers of 2007 Persuasion give us a tortured woman, and steely man who both can and have loved only one. (Penry-Jones cannot be abject and near breakdown nor was Ciarhan Hinds— else endure 8 years away and become a successful pirate for pirates were what these captains were who made such profits—in Austen’s novel she alludes very appropriately to the Giaour, the Corsair and Byron in general.)

Some of the objections to Anne’s final run in the 2007 Persuasion have merit. It may be that the choice of having

Anne run back and forth showed the film-makers had only 4 minutes of movie-time to go and they had to make an ending; certainly having Mrs Smith suddenly show up in the streets to tell half the story with Anne on the run was clearly fitting information in helter-skelter, but I thought the final franticness was a piece with the heroine’s tortured state all film long and it certainly showed renewed determination :). Having Austen heroines run seems to be a way of having them express intense passion; Davies was not the first. In the 1979 P&P after Elizabeth (Elizabeth Garvey) reads Jane’s two letters about Lydia running away, she stands there unable to endure what she feels and then sets out on a frantic run to Pemberley; hers is not as long or as half-crazed, but it is quite a run and she charges into the house to find Darcy reading a book on a couch (how lucky is chance) and then the dialogue ensues. For myself I find that final scene where Sally Hawkins stands there rapt with the emotional pain of too much joy after having thought her loss irretrievable unbearably moving.

As movie-making it’s brilliant neuroticism. Is it that we are to see the film as showing us what damange the modern hard world which dismisses deeply loyal & meaningful personal relationships, meaningful, wreaks on people? I wish I could believe that, and partly do, only I’d like some hint of distance and irony. Without this distance and irony, the films are worrying were we to take them seriously (as we should) as statements of the way women especially are encouraged to look for fulfillment in societies organized to reward those live performatively and coldly for money. Each of the three films (as well as the 2005 P&P) ends with the couple clinging to one another, rapt at having a permanent relationship:

Wentworth and Anne circle in joy

2) On the other hand, the focus in 2007 Persuasion was Anne and Sally Hawkins carried the movie. At its core was a series of scenes with the actress at her diary or letters and climaxed repeatedly in voice-overs. This is unusal in the sense that the vast majority of films have males as the central point of view and it’s said to be (a very small percentage – I could find it) of movies ever have a woman as narrator. This is one thing that distinguishes Austen films. The 1983 MP (which I’m up to studying) has much voice-over with Sylvestre Le Tousel narrating a flow of scenes to make subjective the flow of time and present dramatic scenes:

A rare recent instance of this is July Delpy’s Two Days in Paris. It’s said to give voice and authority to women that is not wanted (or allowed) in public media. So the film by its technique (voice-over, female narration) validates the woman’s point of view.

We might ask ourselves, which of the now available Austen films gives us the female central character as narrator: well off-the-cuff there’s the 1999 Rozema MP, this 1983 MP, the 1996 Emma (with Gweneth Paltrow at her diary a lot), Clueless, Pride and Prejudice of 2003 (Mormon style—not a bad movie, and not all that different on the surface from Clueless, about teenagers and also having Elizabeth as narrator), Bridget Jones Diary (both of the films), Ruby in Paradise (NA film and she too has a diary). And now even Billie Piper as Fanny Price in the 2007 Mansfield Park.

But in all the other cases our narrator is either witty, extroverted or strong and sensible, or at least calm (Ruby and all three Fannys [1983, 1999, 2007]): it’s stunning to have put at the center a tortured soul. A woman in a pit. I wish I could think somewhere behind the discourse is irony (as in Rebecca where we are to see the heroine’s ends up as badly as Rebecca herself to end up in a hotel with the controlling, half-mad enraged Max) but I don’t. This is alas a movie about romance for this anti-feminist time.

To conclude, not only this but the other two short Austen adaptations are just now targets for easy sneers and trashing. It was entirely in character that Ms Newmyer dismissed this 2007 as “a travesty.” I feel the New Yorker article by Nancy Franklin (“Everybody Loves Jane”), which is basically one long sneer at the audience who watches these films is of a piece with the utter contempt displayed for the same audience by PBS in its crude cutting of them. At heart is a dismisssal of the supposed stupid (=female) audience for Austen’s books and films.

Catherine and Isabella Thorpe (Carey Mulligan) in a circulating library, in Davies an occasion for light mockery

How the whirligig of time changes assumptions: in the early 19th century Austen’s novels were described as for elite taste; a liking for them showed you were unusually sensitive, intelligent, had good taste.

Catherine Moreland and Eleanor Tilney (Catherine Walker) walk in the garden, talking of Henry Tilney, in Davies a conversation taken seriously

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Thank you for this, Ellen – I enjoyed reading your thoughts very much and there are plenty of pointers here for me to think about some more. I’m interested in the thought of parts of this version taking off from the 1995 film, as with the Davies version of S&S taking off from the Thompson – my problem is that I never remember the previous versions well enough to pick up on all the similarities and deliberate contrasts!

I did notice that this Frederick seems much less hardened than Ciaran Hinds in the older film, but it hadn’t struck me that, as you point out, Hinds is more believable as a man who has been at sea for all those years and had to live that tough pirate life.

I also hadn’t realised that women narrators were so unusual, or probably I did know this but hadn’t thought about it enough.

It does seem as if a lot of people look for the perfect adaptation of a book and then object to any other version as not living up to the one they have set in their mind as a benchmark – so this ‘Persuasion’ is rejected by many people who loved the 1995 one. I tend to like seeing multiple versions and feel as if each one gives a different angle on or insight into a book… although obviously some adaptations are much richer than others. At the same time it’s a shame that a few classic works get adapted repeatedly and others are never filmed at all.

— Judy Feb 2, 5:14am # - “Both terrific reviews. Thanks Judy and Ellen.

Nick.”

— Elinor Feb 2, 7:33am # - All the shots here of women writing bring me in mind your comments about writers/directors of recent Austen films having a negative view of female readers (specifically Andrew Davies and Robin Swicord). I’m curious – what Austen adaptation (of any typology) contains a portrait of reading women which lacks the malice or spiteful resentment so common today?

— ibmiller Feb 7, 2:17am # - Dear Ian,

I don’t know why all the shots put you in mind of negative views of female readers. Some show women writing and one a pair of young women in a circulating library.

There are a number of Austen adaptations which contain portraits of reading women which are not spiteful. None of the portraits but the one of Prudie is spiteful in Jane Austen Book Club. I’ll cite for beautiful and sympathetic portraits of reading women: the 1983 MP, the 1995 Persuasion (Anne and Lady Russell are seen reading together). Real sympathy is shown the stigmatized plainer girl who partly turns to books to escape the world’s cruelties in the portraits of Mary Bennet in the 1979 and 2005 P&P (the latter show the father empathizing rather than humiliating his daughter for playing the piano; she turns to her instrument to escape). For the free adaptations there’s the 1991 Metropolitan, the 1993 Ruby in Paradise, You’ve Got Mail (a woman who runs a bookshop and loves reading).

Not that this empathy or respect is common. It’s not. But then neither are female narrators—and the Austen films have these.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 7, 7:41pm #

commenting closed for this article