Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Sense and Sensibilities alter the landscape of Austen films · 2 May 08

Gentle Readers,

This is an interim report on what’s happening to my project for a book to be called The Austen Movies.

After watching the 3 Northanger Abbey films back-to-back and writing an essay about them for Jane Austen’s World, and while I was reviewing A Critical Companion to Jane Austen by William Baker for Jim May’s Intelligencer, I began to watch two Sense & Sensibility films back-to-back, the 1981 BBC S&S and the 2008 BBC/WBGH S&S, and demonstrated to my own satisfaction the inadequacy of my previous definitions for three types of film adaptation which I’ll now call apparently faithful, commentary (a good shorthand phrase for the film which means to be both faithful and a critical departure), and free (or analogous and not in later 18th century costume).

Like the ‘81 S&S (and the 1995 Miramax S&S), the ‘08 BBC/WBGH S&S matches the original story, and reproduces most of the characters and central dramatic turning-points & famous lines of Austen’s S&S (with some allowance for modernizing interpretations and necessary as well as advantageous alterations filmic media provides), but it is not faithful. It is a critical departure. The difference is not in the plot-arrangement or what’s left out, since both the ‘95 S&S and the ‘08 S&S are half-way through when they have covered about 2/3s of the first volume of Austen’s story, yet I would argue the ‘95 S&S is as faithful as the ‘81 S&S.

What’s the difference, then? presentation or what Brian McFarland (in Novel to Film) calls “enuncation,” all those elements that make up the moment-to-moment minutiae of the filmic narrative, how its utterances are mediated: what music, light, specific words, mise-en-scenes, “catalysers” (voice-over, type scenes) surround and deliver the literal story, characters, lines, crucial events.

Further, this new ‘08 S&S in its use of enuncations resembles the new generation of Austen films: the 2005 Universal Pride & Prejudice, the 2007 ITV Mansfield Park, Persuasion and Nortanger Abbey, and the 2007-8 combinatory Austen free adaptations (The Jane Ausen Book Club, Becoming Jane, Miss Austen Regrets). None of them but Davies’s NA aims at apparent faithfulness; all show the marks of the romantic retreat for women of post-feminism (seen also Joseph Wright’s 2007 Atonement). The landscape of techniques as well outlook for Austen films has been radically altered.

Early in film, Mrs Dashwood (Diana Fairfax) hangs curtains alone in Barton Cottage (‘81 BBC S&S)

Somewhat more mid-way in film, Elinor (Hattie Morahan), Marianne (Charity Wakefield) and Mrs Mary Dashwood (Janet McTeer) hang curtains together in Barton Cottage (‘08 BBC/WBGH S&S)

Second, I faced up to the reality I’m not going to be able to get sufficient material on the screenplay writers, directors, or commercial decisions of groups of people to be able to root a coherent thorough analysis in comparisons of mini-series belonging to the same genre (say faithful adaptations) from different books. The short essay I wrote on the 3 Northanger Abbey films taught me how comparing the films to the eponymous book worked beautifully well, if I just brought in some information on the three subgenres these belonged to as seen in other instances by the film-makers. (For Austen’s NA, I had an apparently faithful film, the 2007 BBC/WBGH NA; a commentary, the 1986 BBC NA; and a free adapation, the 1993 independent Ruby in Paradise.)

The question then became, should I reorganize the book? Instead of comparing faithful adaptations to one another, commentaries to one another, and then free adaptations to one another, I would compare all the Pride & Prejudice movies, all the Emmas, all the S&Ses, and so on, with a chapter for less known texts (the adaptation of Sir Charles Grandison, Jane Austen in Manhattan, and Austen’s letters in Miss Austen Regrets), and a chapter for Austen movies which combine texts (The Jane Austen Book Club, The Last Days of Disco). And I began to do that with new insights and results in the case of 3 of 4 identified S&S films (the fourth is the 2000 free adaptation, a Tamil I Have Found It).

It may interest you to know that both the ‘81 S&S and ‘08 S&S are 174 minutes, and that for the ‘08 S&S Andrew Davies took material from the ‘81 S&S (written by Denis Constanduros and Alexander Baron) as well as the 95 S&S (written by Emma Thompson); and that Baron/Constanduros and Davies’ films are closely similar in the incidents they dramatize for Brandon: Robert Swan and David Morrisey as Brandon both come early to the Dashwood cottage to bring presents and offer help; in both films Brandon brings books to Marianne; he is there at the party where Marianne is snubbed by Willoughby and helps Elinor wrench Marianne away (the actor playing Brandon carries her in both films); & in the course of both films (though differently) Brandon’s relationship with Marianne is built slowly.

Colonel Brandon (David Morrisey just glimpsed) carrying books to Marianne, she flees before him, & encounters Willoughby (‘08 S&S)

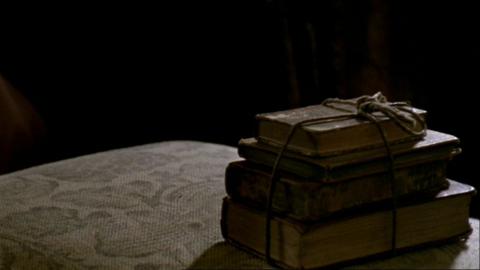

Books remain unclaimed, unwanted (‘08 S&S); there is a still closely similar to this one in the 81 S&S, near the end of the film a well-kept expensive ancient set of books are waiting on the Barton cottage table for Marianne when she comes in from a walk

Penultimate scene of film, Colonel Brandon (Robert Swann just glimpsed) succeeds in giving Marianne (Tracey Child) his present of books to her, Mrs Dashwood (Diana Fairfax) looking on (‘81 S&S)

This switch is not a small matter, but as I rearranged my lists, it came to me in each case I would have fewer films, a strictly delimited set of filmic texts to place against Austen. This would allow me to discuss Austen herself—whose books I love. I could see myself beginning to write say at the end of the summer after comparing the 9 available P&P films thus far to Austen’s book and one another. This sounds like a lot, but I have already compared two of them carefully (the 1979 BBC P&P by Fay Weldon and the 1995 BBC/A&E P&P by Andrew Davies). Then I could go on to the 4 available Emma films. Each chapter would be done separately the way I did my book on Trollope. There are available 3 Persuasion films, 3 NAs, and 4 Mansfield Parks. And when I had them all together, I could revise the texts into one whole as I did my book on Trollope on the Net. I had not been able to envisage how concretely to found my chapters before. (It is important to have a limited mechanical plan for a book.)

However, as I proceeded I began to see so much that is valuable and intelligent and enrichening in the ‘81 S&S which it shares with his “sister” films made in the same generation (say 1972 to 1985); among them, that it really is a woman-centered film, an kind of ecriture-femme in filmic terms (e.g., it offers a serious portrait of the mother & her relationship to her daughters, it has social lengthy scenes of women interacting) and I don’t see how I can do this justice unless I keep to my original organization. So I’m in a quandary while carefully watching the ‘81 and ‘08 S&S films. Probably though I will switch since switching has made me glimpse a procedure by which I could do the book chapter by chapter.

For the sake of those readers who are particularly interested in the Austen films, I’d like to close this blog by saying my thinking has also been influenced by a discovery. Last week a couple of people on Austen-l told the group yet another mini-series of S&S has become available: Proxis.com has reprinted in DVD form a 1971 BBC S&S, a 180 minute series. The ‘71 S&S is thus 6 minutes longer than the ‘81 & ‘08 S&Ses. It may be purchased at Proxis.com (a Dutch site):

I bought it and yesterday discovered the screenplay writer was Denis Constanduros (who wrote the apparently faithful ‘72 BBC Emma and the outline used by Alexander Baron for the ‘81 S&S), the director Martin Lisemore (he directed the ‘74 Pallisers I’ve been studying, the brilliant ‘72 Golden Bowl & ‘76 I, Claudius), and the woman who plays Elinor Dashwood is Joanna David. She played the lead role in Lady’s Maid’s Bell (she was also Mrs Gardener in the BBC/WBGH ‘95 P&P). So I now have more information on these film-script writers, directors and acting crews.

And I have perhaps my first example of the previous generation of faithful films. The first mini-series from a high status older book produced by the BBC is said to have been of Trollope’s The Warden in 1951. The first two mini-series from a Jane Austen book occurred in 1960: 6 half-hour installments adapted from Emma; 4 half-hour installments adapted from Persuasion. A third occurred in 1967: 6 half-hour installments adapted from Pride and Prejudice. Is this ‘71 S&S the last of these older adaptations? That is, does it resemble them, or is it more like the faithful adaptations I have been studying. If the latter is true, then there were a startling 2 apparently faithful versions of S&S done during that era.

Stay tuned.

I hope I have not bored you, gentle reader.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- No, you have not bored me at all. I think it’s a good idea to arrange the material according to the original resource material.

As art historian, I can compare your choice to the basic approaches in my discipline: either the material is organized according to style or according to subject.

When you look at a group of works of art which are similar in style (a room full of Impressionists), the different subjects stand out. When you look at a group of works of art with similar subjects (a room full of family portraits), the differences of style emerge.

You can always in the course of your discussion cross-connect films from earlier chapters, if you feel like it. But I think that by comparing the different versions back to back, the differences of genre will emerge clearly.

Sorry if this was irrelevant.

— Lila May 2, 10:21am # - Dear Lila,

Not at all irrelevant. A great help. When you give me the analogy of the art historian trying to decide whether to organize by similar subjects or similar styles, you make the case I needed to have made for me.

I love art history by-the-way. I read it when I can. My love of film is also a love of visual mise-en-scene. There are some classic art histories where the historian moves by styles (Wolfflin) but as I recall he has such a vast sweep of time each "style" covers a century and I wouldn't be surprized if he chose pictures with the same content. They also don't have a source in the way of a film adaptation; except in the case of a very few religious icons, there is no previous text the painter is expected to cling to literally.

Ellen

— Elinor May 2, 11:14am # - “Dear Ellen,

Can you email me your review of Baker’s AUSTEN COMPANION please? (IS this the same Wm. Baker who does Geo. ELiot/GH Lewes?)

You began your latest Austen film piece with “Gentle Austen reader”? You did, didn’t you…. What do you believe an/the Austen reader is gentle? Don’t upbraid me just yet. I must confess I’ve not yet read the entire piece, but still…..?

Tom”

— Elinor May 3, 6:50am # - Dear Tom,

I’ve attached my review to an email to you—I’ll put it on my website after it’s published.

Why do I call Austen readers “gentle readers”? I wish they were. In fact Austen-l and Janeites are often acrimonious: Austenites and Janeites have often invested or created a kind of identity for themselves out of the books, and it’s common for this to be deeply reactionary; academics often interpret her as mildly subversive, proto-feminist, and place the books in political issues of the day and today too. This results in arguments. Among the most recent generation of Janeites (as Austen readers spread out those who are just reading sequels or have seen the movies, and those who see her as sheer Regency romance), you can find on Janeite blogs, snarky, mocking, deliberately anti-intellectual posing against any sensitivity. The new non-feminists take on the worst macho traits. I find Austenblog awful.

So what I’m doing is creating my reader, I am conjuring all Austen readers to become “gentle readers” —for along with those who openly quarrel there are still a huge number of readers (maybe not those who write on the Net) who match Austen in intelligence and (when she wants to evince this amid her satire) an understanding of what kindness and generosity of spirit is.

I’m idealizing too. I’m trying to drop the pseudonyms for Jim and myself since they are somewhat stilted and inconsistent. It’s hard because I have trouble writing when I don’t think of myself as writing to someone. So more simply I use “gentle readers” to conjure my readers not to be sarky, nasty, mocking and other very unpleasant things (spiteful? resentful) but rather decent and candid (giving the best interpretations to motives and events) in Austen’s sense. I don't want abrupt discourtesy; I will delete reactionary aggression & any trolling.

Ellen

— Elinor May 3, 6:57am # - I’ve decided on my new plan. I’ll have 9 chapters. I’ll write the introduction last.

First up will be Chapter 2, and that’ll begin with an exegesis of Austen’s S&S and move on to the 5 S&S movies available to me and what I know of others. By beginning with S&S I can set a tone or point of view about Austen which comes out of that book where her romance and comedy is (in Hazlitt’s words) “the equivocal reflection of tragedy in everyday life.” Instead of screwball comedy as the basis of movies (which is what movies meant for mass distribution in theatres have clung to from the 1940 P&P to the 2003 Bridget Jones Diary, and Emma Thompson's 1995 S&S caricatures come from this), it will be the mood of the early mini-series, woman-centered, Chekhovian at best.

The line up would be Ch 3 (Austen's P&P & 9 P&P movies), Ch 4 (Austen's MP & 4 MP movies ) Ch 5 (Austen's novel & 4 Emma movies), Ch 6 (ditto & 3 NAs) Ch 7 (ditto & 3 Persuasions), Ch 8 (the unusual texts (movies from Sir Charles Grandison, the letters), and Ch 9 combinary free adaptations (e.g., JA Book Club, Last Days of Reason, among others). As I go along I’ll discuss them in terms of their subgenres, what I can learn about their writers' other work, and the generation(s) of movies each belongs to, and other sources beyond Austen (other movies, other books too).

A doable plan.

E.M.

— Elinor May 3, 8:07am # - Dear Ellen,

An excellent, thoughtful post! I especially like how you’ve pulled the excellences and inadequacies of each film out, as well as the division of time periods of adaptations. And I think your new organization is great.

I am curious as to what you would call the 2008 S&S – since it is a critical departure in enunciation, and thus not an apparently faithful adaptation. Is it a commentary with faithful traits, or a new category entirely?

I might not place the 08 S&S quite as closely to the 05 P&P and the 07 MP, since those seem to have been made for primarily commercial reasons, while Davies and Pivcevic (and whoever produced NA) seemed to have a much better grasp and concern for Austen’s work (though, of course, they have their own interpretations). I just get the sense that Joe Wright and Maggie Wadey and their artistic teams are more concerned with making a film which reflects their sensibilities and concerns, regardless of Austen’s, while the other films are more sensitive to Austen.

I look forward to hearing more about the 71 film, although I wasn’t as happy with Constanduros’ interpretation of Emma (primarily in his adding unnecessary and unnaturally flighty dialogue for Emma).

I think your comment on “gentle readers” is a much needed point. I know I have certainly constructed a Janeite identity (somewhat reactionary, but I hope in a mostly positive and constructive manner) for myself, and I can get upset and react negatively when that identity is challenged, though I attempt not to. I am strongly against the idea of Jane Austen as pure romance, but I also find much of the current snarkiness and unkindness awful (and hope I don’t contribute too much to it). Your ideal of readers with “kindness and generosity of spirit” is a good one, and one I hope grows in popularity.

Ian

— Ian May 3, 11:20am # - It sounds like a great plan to me and I will look forward very much to reading it. I also look forward to hearing what you think of the 1971 S&S.

And I’m glad to see you have managed to turn the comments back on.:)

— Judy May 3, 5:15pm # - Thank you, Judy, for the encouragment, and Ian for the comments on “gentle Austen readers.”

Ian, right now I’m inclined to stay with three categories. Davies S&S represents no more (or less) radical departure than the 1940 P&P (which is very different from Austen’s novel), or the ‘86 NA or Rozema’s critical commentary in 1999 of MP (she rewrote Austen’s book to criticize its politics).

His techniques for departure are different because his film participates in new aesthetic techniques and a further development of older ones I find in the other shorter films for commercial theatres and recent mini-series. Maybe I’ll try to talk about some of these on this blog.

Have you read Leitch’s book, Film Adaptation and Its Discontents? It shows the futility of having too many subdivisions or categories. He has the idea of being more nuanced to be more useful, but he ends up with way too many types of adaptation to be useful.

In my view all these film-makers show a similar mix of commercial and artistic motives. The genuine devotee of Austen (e.g., Emma Thompson) is rare. As I’ve argued here I don’t think Davies is one of these; his outlook on social life, on sex and his strong tendency to carnival sceptical caricatures is very much at variance with Austen. I loved Constanduros’ take on Emma: he seemed to me really to present her from a distanced ironical point of view; thus, I look forward to seeing his version of S&S.

Ellen

— Elinor May 4, 12:57am # - Back again, thinking: Davies’s S&S brings out puzzles about what people are referring to when they call a film faithful or unfaithful. Like Baron's 1981 S&S, Davies includes Edward’s visit and Willoughby’s confession, and in Emma Thompson/Ang Lee’s 1995 S&S, they eliminate both. Yet “all” who discuss the Thompson/Lee movie call it faithful, and the Davies’ film was continually accused of non-faithfulness.

The comparison of Davies’ 2007 NA to Wadey’s 1986 NA produced a similar kind of contradiction. The 1988 NA included far more of Austen’s original words, was closer and true to the discussions of art and taste in the book—all of which were omitted by Davies. Yet Davies' is the faithful film, and I have to say Wadey’s is the commentary or departure.

It’s more than enunciation that causes these kinds of faultlines, for the Thompson/Lee film is highly romantic in its enunciation (if not Byronic or Bronte-like in its film imagery).

I am much happier now I have a workable plan, and I credit Davies's S&S for this. I began to see my inadequacy at the time I wrote the blog called "Typology all Screwed Up."

Thinking aloud,

Ellen

— Elinor May 4, 1:33pm # - From Cynthia:

“Ellen,

I’d love to read what you are writing about Sense & Sensibility.

It’s one of my favorite movies. For one thing, Alan Rickman is fabulous. Then Ang Lee’s framing of every scene so beautifully, and of course Emma Thompson’s screenplay rocks. I think the casting is great. It’s also very pretty to watch! I think Kate Winslet lied about there age to get hired.

I used to watch it when stressed out. It always relaxes me. My son and husband sometimes say, “How are you? Is it going to be a Sense and Sensibility night?

Cheers,

Cynthia”

— Elinor May 7, 5:25pm # - Do talk about the techniques – I’m very interested. I haven’t come across Leitch yet – but will look out for him.

I’m not sure I’m comfortable with describing Thompson as a genuine devotee of Austen – at least, not in saying that she’s more of one than Davies. While I agree that Davies’ social ideals, emphases on sexuality, and tendency towards a less subtle character painting are not completely in sync with Austen’s, I think that Thompson’s work, especially her assistance with the 2005 Pride and Prejudice, indicates a similar variance, though in possibly different directions. Additionally, though I have gone line-by-line through her screenplay for Sense and Sensibility and believe that upwards of 70% of the dialogue is either directly from Jane Austen or slight variations thereof (and those often the wittiest and most intelligent), the fact that she believes there only to be five lines from Austen in her own work seems fairly significant. Additionally, Thompson’s Sir John Middleton and Mrs. Jennings (Robert Hardy and Elizabeth Spriggs) were much more caricatured in my viewing than Davies’ versions of the characters (particularly Mark Williams’ Sir John).

As for Emma, I think that while Jane Austen keeps enough detachment from Emma to be honest about her flaws, I have never been ironically distanced from her when I’ve read it. That’s probably because I have always intensely identified with Emma’s failings and intentions, which doesn’t allow for a whole lot of distance.

I actually think the Davies and Thompson films are fairly comparable in faithfulness, in their own interpretations. I’m also not sure that the claims of Thompson’s faithfulness are quite as universal – in Jane Austen in Hollywood, several of the essays pointed out that reviewers were pleased when Thompson departed from the novel, particularly in enhancing the male roles (which is also what Davies has talked most about). I think that the reviews on Davies’ film are both hard to measure and clouded by the issue of comparing it to the previous film(s). On the boards and blogs I read, I noted about half of the reviewers claiming it was faithful. Overwhelmingly, I think the sentiment was that it was a nice complement to the 1995 film, with some liking the older one slightly more, and some liking the 2008 series slightly more (myself falling into the latter category).

As for Romantic enunciation, I think of all Jane Austen’s novels, Sense and Sensibility (and perhaps Persuasion) fit the Romantic style best. The passions run high in the other novels, but they come to the surface more often in these two (whereas the kind of Romanticizing that occurred in the 2005 Pride and Prejudice really didn’t fit, I thought).

— I. Miller May 7, 5:38pm # - Dear Cynthia,

I apologize for taking so long to get back to you. I think you are onto something: what I’ve discovered is continuously throughout the 1995 S&S several strains of soft melodious music, often play flowingly, floatingly. The key tune is Dowland’s (played first by Marianne at the important moment Brandon first sees her), and the lines are “softly softly where peace and rest are reconciling.” The words are not repeated but the tune is.

The scenes in the movie repeatedly open and close with soft voices heard in the distance. The landscapes are deeply appealing greens, lakes, picturesque trees.

In short, the film invites us to dwell in a haven of idyllic quietude.

Ellen

— Elinor May 8, 11:08pm # - “Ellen,

I found (and was disappointed) that on the soundtrack they left out Kate Winslet singing these lines (or similar . . . softly sleeping . . .) at the pianoforte. Maybe it was not her voice? Even if it was not her, they really should have included this important piece of music . . . it is so central. Dowland’s and the lines softly softly where peace and rest are reconciling …

I[‘ve] also watched The Secret of Roan Inish so many times that I wore out a VHS of it. Both films have sad, lovely music and mournful undertones, wonderful acting, strong girl characters, and happy endings …

Cynthia”

— Elinor May 9, 6:18am # - In response to Ian,

I’ve taken thus long to get back to you because I don’t know where to begin. I can't write essays in these comments. So briefly,

I am going through Thompson’s screenplay too, and unless you have some new (very loose) definition of verbatim quotation, she is right. There is little verbatim quotation. She paraphrases, abbreviates, reverses, omits; very little of the original text has survived. A comparison might be the 1979 P&P where a startling & unusual amount of verbatim quotation from Austen is found. Very hard for the actors but they and especially Elizabeth Garvey came up to it.

I don’t know why you bring up the characterization of Emma in Jane Austen here. I didn’t bring it up. I was talking of the Emma films in general. I can take this as an opportunity to say (in case you don’t know this yet), there’s a new book out on the Emma films: Emma adapted by Marc DiPaolo.

I’m carefully going through 3 of the 5 Sense and Sensibilities right now (I include I have found it in that five). Like the ‘81 Baron/Bennet S&S, the '95 Thompson/Lee S&S after an initial rearranged opening has a script you can follow from chapter to chapter in Austen; you can’t begin to do that anywhere in Davies’ ‘08 film. He ranges wide and goes back and forth, sometimes redramatizing the same scene in Austen several times in his film since he wants the Willoughby material to climax in the middle of his film. It climaxes 2/3s the way through Austen’s first volume and in a comparable place in the ‘81 film and not far off in the 95 S&S. What I called enunciation though is what is so startling, and I’ll argue that is so different from what is associated with Austen and changed in inference that the ‘08 S&S is comparable to Rozema’s 1999 MP in that both criticize, replace, and develop Austen in directions she doesn’t foresee in her books. I heard mostly complaints about the ‘08 film (I didn’t count) that it was unfaithful as this is the cant complaint. Who cares what fools who work from impression think? I don’t. The definition of accuracy is their literal memories of what struck them. I’ve now heard how Cranford is faithful to the book of short stories by many people. Absurd on the face of it as the movie combines 3 texts by Gaskell.

If you think Austen a romantic in the way you suggest, we are so far apart fundamentally, we haven’t got common ground. Your comment shows me the problem of leaving concrete objective criteria such as I had; I then have to try to develop concrete criteria for enunciation -- which is what McFarland tried to do, and I'm not sure he managed. I have to reread his book.

Ellen

— Elinor May 9, 2:05pm # - In response to Cynthia:

Your description of your response to this movie confirms what I think is part of its extraordinary power. I feel an important theme in it (one not really in Austen or only in the nuances of her language) is the idea of retreat; Thompson changes Brandon’s disillusioned words, Edward’s idea of a life for himself and jokes like “piracy is our only option” to suggest we not desire the glittering prizes or admired people of the world. I would hazard the guess that the film resembled The Secret of Roan Inish more closely for real than it does Austen’s book. Part of the pull of all the Austen movies for women is they present strong female characters—in private life. They have female narrators (not common in movies) and a high degree of epistolarity in scenes (this begins with the 79 P&P and 83 MP).

My younger daughter loves the ‘95 S&S too. She’s watched countless times.

Ellen

— Elinor May 10, 12:14am # - Dear Ellen,

I don’t think I called her lines “verbatim,” but instead “directly from.” I don’t mean that they are exactly, to the word, what Jane Austen wrote, but that they are well within the range of “faithful” dialogue – certainly within Andrew Davies’ spectrum in “Pride and Prejudice,” with a general keeping of key phrases, with minor restructuring, deletion, and occasional modernization/clarification. An example of what I mean is Edward’s line in Chapter 19:

“I always preferred the church, as I still do. But that was not smart enough for my family. They recommended the army. That was a great deal too smart for me.”

The Thompson line is:

“I always preferred the church, but that is not smart enough for my mother – she prefers the army, but that is a great deal too smart for me.” (Scene 28, p.49 in my edition).

When overlaid, the line looks something like this (Words in both screenplay and original in plain font, original text only in []brackets, words only from the screenplay in parantheses):

“I always preferred the church, [as I still do.] (b)ut that (is) [was] not smart enough for my (mother) [family.] (– she prefers) [They recommended] the army, (but) (t)hat (is) [was] a great deal too smart for me.”

The line shows (to me) the same sense and very funny wit of Jane Austen’s line (it’s my favorite line of humor from the film). There is one phrase completely deleted, the tense has been shifted, and the subject moved from his family to his mother. I hope that clarifies what I mean by “directly.” I certainly don’t mean to imply that I thought she had a huge number of copied down lines, but I haven’t noticed that practice in any of the films, apparently faithful or not..

As for Emma’s characterization, I thought the comment, “I loved Constanduros’ take on Emma: he seemed to me really to present her from a distanced ironical point of view,” referred to her character as presented in the film, to which I responded, perhaps somewhat tangentially, about my views of how I view Emma’s character as presented in the book.

I had heard of Professor DiPaolo’s book, and hope to get a chance to read it carefully soon – it looks quite exciting (to an Emma fan, at least). Thanks for the recommendation!

What I mean by “Romantic” perhaps unclearly stated by my last paragraph, and I apologize. What I see as the “Romanticism” in the films of “Persuasion,” “Sense and Sensibility,” and the 2005 “Pride and Prejudice” is the championing of open expression of emotion and of individualism over societal demands and duties. I do not see Austen advocating either of those things in any of her works. However, I do see emotion more openly expressed in “Persuasion” and “Sense and Sensibility,” leading to my understanding of why filmmakers would adopt tropes of Romantic-era stories (lots of rain, emotional declarations, etc) to those stories more comfortably that to the “light & bright & sparkling” “Pride and Prejudice.” I’m not sure that clarifies my position, but I hope it does.

Ian

— Ian May 10, 10:31pm # - Dear Ian,

I apologize for taking so long to reply. Our debate is over whether one sees a half-empty or half-full glass.

When I look at these lines in Chapter 19, I am struck by how much has been omitted; by how it is not said by Edward to Elinor while walking in a park at Norland and thus a speech where (unacknowledged but implicit) they are discussing their views of life and how they want to live (so marriage). In the novel this speech occurs well after the sequence at Norland, and when Edward comes to visit Barton cottage -- omitted from Thompson/Lee film as well as Willoughby’s reappearance and confession. Edward is explaining his melancholy to Mrs Dashwood; it’s surrounded by a wholly different dialogue.

My sense is of transformation, apparently faithful. There are others instances where lines are joined from different scenes and the same kind of change of venue, change of character, change of purpose and tone occur.

So when Thompson said she had a tiny percentage of copying, she seems to be describing her experience of writing an outline and rewriting the book as an adaptation, and these bits of dialogue that turn up verbatim (just about) were in her mind transformed.

There is a real problem in defining what we mean by a faithful film if we want objective consistent criteria. I’ll write a blog on DiPaolo’s book when I’ve finished it. It’s useful but has some central problems, among them his way of defining the different types of adaptation (which he partly then uses to judge a particular film).

I feel the 1972 Emma is a rare anti-romantic take on Austen’s books, and I don’t think they are fundamentally romantic, by which I mean just this open and trusting expression of emotion and belief in real empathy between people. Austen was strongly sceptical, satiric, and did more than seek a compromise between social needs and individual desires; she looked for safety, for peace of mind and heart (as well as outlook); she shows a stern morality and exposes the outrages of daily life rather than justifies them.

I am in sympathy with Scott’s demur about Austen's Emma at the close of Scott's review where he implies that finally he is disappointed by the underlying message of her books and writes: “the youth of this realm need not at present be taught the doctrine of selfish. It is by no means their error to give the worlld or the good things of the world all for love.” He would probably like the movies’ romance. But there is more to sexual risk and more about women’s position central to the novels' perspective that Scott seems hardly aware of in his novels.

Ellen

— Elinor May 17, 5:41pm # - Dear Ellen,

Thanks for your kind words on my blog. While I was only presenting my undergrad thesis, I will try to remember your experience as I move on to graduate work.

I think you’ve hit upon our difference in approach exactly. I think that my personal reaction to lines that similar is purely verbal, and I tend to be so excited by the words themselves that I tend to forget the context. Although I do get quite put out by changing the speaker of a line (as the 2005 P&P did a few significant times, as did the 1980 version).

Oh, now I have more to look forward to – Emma Adapted post, an Austen Films book, most posts…

I think your description of Austen as strongly skeptical, satiric, and desiring safety and peace of mind and heart as well as sternly moral and uncompromising. I’m not sure I go quite as far in seeing Austen’s rejection of belief in real empathy between people – I definitely see her as knowing the limitations of verbal and emotional communication, as seen in her handling of the proposal in Emma, but I don’t think she believed it was impossible, merely extremely hard and neverending. I think that’s why I’ve never quite accepted Scott’s assessment of Emma.

Thank you for taking time to discuss.

Ian

— I. Miller May 19, 10:46pm #

commenting closed for this article