Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Austen Unchapmaned · 1 June 08

Dear Tom,

Thank you very much for your reply on the different texts in modern editions of Austen’s novels. If you would be so kind, I would be so grateful if you could send me copies of the TLS correspondence showing Janet Todd’s replies to the strictures and complaints about the new Cambridge editions. I hope this is not troublesome to you.

The question to ask (as I understand it) before returning to the first editions of Austen’s texts is, Are the differences between the original published texts and Chapman’s edited versions so frequent and pervasive to leave a different impression and change the meaning of the text significantly. While I admire Kathryn Sutherland’s Jane Austen’s Textual Lives and her editions of the early biographies and essay on the creation and history of the perceived story of Austen’s life enormously, I know that some of Sutherland’s arguments in JA’s Textual Lives depended on overreading of manuscripts. Has she overstated the case for viewing Chapman’s texts as misrepresenting Austen? When I look at Janet Todd’s reply I’ll look to see if she makes the argument Sutherland is exaggerating the differences.

On the face of it, we want the author’s intentions and not someone’s improvements, but Austen died young, too young to have second thoughts. We also don’t know what the printers in-house did to her manuscripts—we can’t as they don’t survive for the 6 famous books. I’ve seen where scholars produce an unreal text by going back to the author’s manuscripts or a first edition. In the case of Walter Scott, the very first editions of his novels were changed and corrected from his manuscripts by him; the later editions were changed yet further and it was he who enriched them by adding prefaces, appendices, and corrected. The latest Edinburgh editions actually go back to manuscript texts that have never been published as they appear; the editors leave off all Scott’s prefaces, appendices, and the other paraphernalia and paratexts Scott added over the years. In my opinion (not a Scott scholar but a reader of Scott), the reprints of these Edinburgh new texts are maimed and much diminished: to read say Kenilworth in the Everyman is to read a text embedded in paratexts, and it grows so much richer. It’s true some of Scott’s later explanations are fabrications (hard word but there it is), but why did he fabricate what he did? The editors of a Scott text should include the fabrication and in their introduction explain the discrepancies between what really happened when he published a book or wrote it as far as we know about it, and explain why he lied as far as they can. The Edinburgh editors have acknowledged that readers want these paratexts by having them separately published as two volumes at the end of the whole set. That’s no good, and it’s expensive. Who wants to read a book that has been (in effect) divided up and you have to buy in in different books. I suppose this procedure might force libraries to buy more books :), or the whole set (prohibitively expensive for common readers, but individually now reprinted in select cases by Oxford and Penguin paperbacks). Perhaps Scott’s never before published original manuscripts are of enormous interest to scholars but as geologizers, and not to readers seeking to enjoy Scott’s full creative intentions.

When Chapman sat down during and after (in the 1920s) his traumatic experiences in World War One, did he really simply edit Austen’s texts scrupulously, carefully, and change the meaning very little? It’s commonplace to correct grammar, spelling and other mistakes—usually nowadays it’s a case of typos too. Or did he make a wholesale correction wrongly? Are the first texts of Austen’s books sufficiently different from Chapman’s early 20th century editions to liken the difference to that between Richardson’s first edition of Pamela (a delightfully prosaic demotic style which projects a servant girl) and his last (the text is turned into something stilted and euphemistic)?

All that said, perhaps the Cambridge people simply skipped a step. It’s a time-consuming arduous business collating editions even when there are only a few. So the perhaps Big People relied on their prestige and our desire to read their Important Interpretations and choice of appendices and didn’t collate texts, only corrected the second editions of Austen by the first or vice versa.

The way to tell of course is compare a text which is Chapman’s with a text reprinting the unChapmaned Austen. So I have now ordered the recent new Penguin of Mansfield Park by Kathryn Sutherland because the “search this book” function tells me that the table of contents includes a couple of page note on the text and an argument about the first text in the edition introduced by Tanner. Is that enough? Which new Penguins do you have and do you recommend any?

I’ll conclude by saying I have different favorite editions of a particular text of Austen’s as I do for Trollope—for his novels the 1970s editions of the Penguins are unbeatable, superb. In her case though I can’t say that any particular editions by a publisher in a particular era are generally the best. It seems to me each edition is so influenced by the particular editor, and if one person is chosen to write all the introductions (as in the case of a Signet set where Margaret Drabble did), no matter how brilliant the critic, she can’t really sustain herself as the best across all the novels. It’s so individual: Marilyn Butler’s 1995 Penguin edition of NA is superb: wonderful reproduced illustrations of abbeys around Bath, introduction on consumerism, really informed notes about gothic novels, mostly Radcliffe, Austen is parodying. Patricia Meyer Spacks’s afterward in a Bantam of Sense and Sensibility (the same cover may be found on Diana Birchall’s Mrs Darcy’s Dilemma) is just about the best essay on S&S I’ve ever read. I’ve come across just great Broadview editions of a novel, everything in it you’d want (June Sturrock’s Mansfield Park, with contemporary documents on slavery, colonialism), and others embarrassingly thin, where the stuff chosen is for a narrow agenda associated with the editor’s and his or her friends. Ditto for Longmans and Nortons.

In general what matters is 1) the text (in Trollope these differ importantly); 2) the introduction, notes and appendices, and 3) the cover. For me Tom the cover also counts. A cover illustration which misrepresents the content, debases or pornifies it, is enough to make me refuse to buy a book. The latter are to me books set up in basic bad faith: I find disgraceful the Norton Mansfield Park where Claudia Johnson puts a portrait said to be of Austen (sexy, coy, unreal) which has repeatedly been shown not be her. My favorite editions are ones which use the picturesque as part of the cover (as in this Norton for Persuasion, a well-known contemporary print landscape of Bath), either in the image itself or some decoration around, or substituting for, an image (e.g., an effective suggestive bird cage).

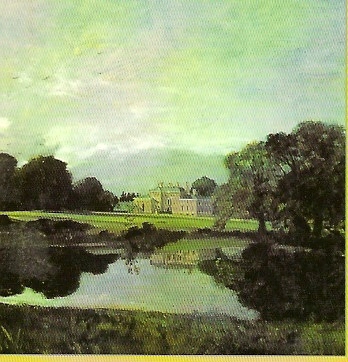

Here is one of my favorite older Norton cover images for Pride and Prejudice, a very early 19th century Malvern Hall (by Turner) suggesting Pemberley:

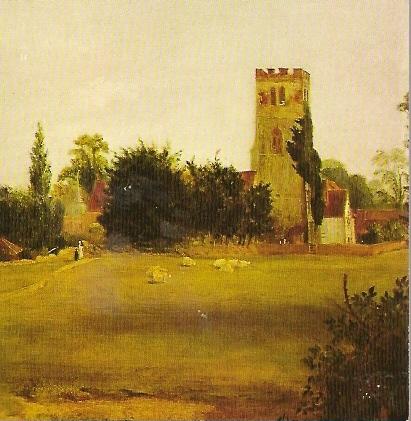

I love this one too, a very appropriate image (I don’t know the name, author, provenance) for an older Signet edition of Mansfield Park (introduction by Margaret Drabble). Particularly effective and right is the inclusion of the small walking figures:

In the comments the reader will see mentioned the cover illustration for the Broadview Press edition of Mansfield Park. Here this is:

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Hello again, Ellen,

I’ve just written a long comment to your previous post which touches on some of the issues you raise here. I wanted to add, on reading this, that I agree with your assessment of the value and integrity of Chapman’s editions, where an enormous amount of labour has quietly and unassumingly gone to producing a beautifully lucid and readable / usable text. At least as far as MP is concerned, however, he did change a great deal of the punctuation, and when you have Kathryn Sutherland’s edition you’ll see how what Chapman ‘corrected’ can stand unrevised yet still carry meaning and significance.

I like the Broadview edition too, but I can’t quite accept the photograph on the front cover, simply because it IS a photograph. It jars.

If you have any particular questions about the process of editing the Cambridge MP I can try to answer them. I was not directly a part of the work at the collation stage, but I know what was involved.

— Laura Carroll Jun 1, 7:49pm # - From Tom:

“Dear Ellen,

Many, many thanks for your thoughtful reply. I appreciate it. I will send you via UPS tomorrow the TLS exchange, beginning with Sutherland’s Commentary article, a letter from Todd, then a reply also in the letters column by Sutherland, accompanied by Simon Jarvis’s (?) omnibus review of 4 (I think) Austen-related titles. You should have them by Tuesday or Wednesday the latest.

Penguin publishes the first edition texts (I’ve got them all). Cambridge uses the latest version that Austen herself probably had a hand in. Any textual changes are footnoted at the bottom of the page so that the reader can see very clearly how many changes were made and what they were. Of course, this would apply to Sense & Sensibility and Mansfield Park. The 1st ed. of P & P was used because Austen herself had no input into the 2 later lifetime editions.

Cambridge says they hope to bring the whole set out in paper sometime (after they recover their costs). I see on their website today that a 9-vol clothbound set of all volumes should be available this November for about 500 GBP. Although I don’t own any of the novel volumes I’ve looked them over in the library and the production values are very high. CUP really did a nice job on them. (I hope they do as nice a job with their Richardson project – I’m already saving up for these…). I DO have the Jane Austen in Context volume in cloth, I’m pleased to say.

This is a start. I hope it helps some. As always these days, in haste….

Tom”

— Elinor Jun 1, 8:13pm # - Dear Laura and Tom,

I couldn’t agree more heartily with Laura about the cover photograph of the Broadview Mansfield Park edition. I have to admit though that for me it’s not that the depiction is a photograph; it’s a photograph of a woman with a very glum expression on her face dressed in a Victorian outfit. What does either necessarily have to do with Austen? This is not the only Broadview edition to jar in this way: they persistently use later Victorian photographs; for books published in the 18th century they are inappropriate. They are also often of individuals whose expressions or doings have only slight or strained connections to the book. The Broadview edition of Sense and Sensibility has a photograph of two women in Victorian dress, this time with a solemn expression is on their faces. I suppose the connection is two women = the two sisters, but that’s not enough to overcome the jarring.

I have friends who been editors of Broadview texts and have been told early on the individual editor is informed she or he will have no say about what is on the cover. Nonetheless, or despite this questionable decision for the covers, I grieved to learn the other day that Broadview has gone out of business. They were providing fine editions of texts for affordable prices, texts which otherwise you would have to go to a rare book room to read.

Dear Tom, thank you for the clear explanation of the difference between the new Penguin and the new Cambridge texts. I look forward to reading what you are sending, especially Jarvis omnibus article. This is really wonderful of you. Many thanks.

Ellen

— Elinor Jun 2, 6:48am # - P.P.S.

It’s apparently not true that Broadview Press has gone out of business. According to someone (I hope) knowledgeable on NASSR-l (a romantics list): “There was a Broadview representative at ASECS Portland who said that Toronto UP is only taking over the Social Sciences series, while Broadview itself will continue to publish their English and philosophy series.”

— Elinor Jun 4, 6:09pm #

commenting closed for this article