Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

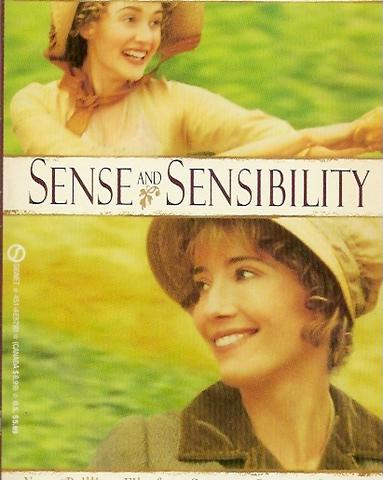

"Ours is a competitive business, sir:" the latest Oxford _Sense and Sensibility_ · 1 July 08

Iconic image for every S&S film: the journey of the displaced women (2008 BBC/WBGH S&S)

Dear Friends,

As I wrote more than a month ago now, I was delighted when Laurel of Austenprose asked me to join her in writing reviews of the recent reprint of the Oxford standard editions of Austen’s novels. I’d get to gaze at the different covers, read introductions, notes, appendices, and if any were included, illustrations. As you might have guessed, I’m one of those who partly choses to buy a book based on its cover. I enjoy introductions (occasionally more than the story they introduce), get a kick out of background maps and illustrations, and especially ironic notes.

Looking into the matter I discovered I’d have to sleuth what if anything was the difference between these new reprints and the earlier reprints of James Kinsley’s 1970-71 edition, from which all the subsequent Oxford texts have been taken. Why after examining the early texts did Kinsley made the choice to reprint R. W. Chapman’s 1923 edition of Austen’s novels with some emendations? Hmm. My curiosity made me unable to resist checking the Oxfords against the other editions of Austen’s novels I own. In the case of Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, a novel I first read when I was 13 and the one closest to my heart, I own 14 different editions and reprints, and French and Italian translations1.

The more cynical and less devoted reader of Austen may well say, wait a minute here. What would be the point or interest, since probably the differences in the texts themselves would be miniscule, the paratexts just the sort of thing Catherine Morland would have skipped, and this upsurge of proliferating books simply the result of a highly competitive marketplace. But that’s the point. We can ask why provide all this if the goal is to produce an inexpensive handy text and the motive profit? The answer comes back that Austen’s novels are at once high status, beloved, and best-selling texts which keep selling because they’re best-selling books. They have highly diverse and conflicting groups of (let us call them) consumers. So in order not to offend and to persuade as many readers as possible to buy at least once or yet again, publishers are driven to produce books which are informative and pleasing, accurate and accessible—and up-to-date. Since the reprints cover more than a quarter of a century, we may watch different introducers struggling to present their respective agendas, which, like the changes in the covers of the books, reflect the ever-changing climate of a surprizingly stormy Austenland.

Mrs Jennings (Patricia Routledge) retelling the rejection and disinheritance of Edward Ferrars—shaped by comic anguish in 1971 (BBC S&S)

We also had more than the famous six books because since 1980 Oxford had chosen to accompany Northanger Abbey with Lady Susan, The Watsons, and Sanditon, Austen’s lesser-known novels (the first epistolary, the last two unfinished). Laurel and I had an intriguing journey ahead of us.

We agreed we would form diptychs each time. Sister reviews, each one a counterpart to the other. So, to begin with S&S, here is Laurel’s posting:

“Pray, pray be composed,” cried Elinor,” and do not betray what you feel to every body present. Perhaps he has not observed you yet.” Elinor Dashwood to her sister Marianne, Sense and Sensibility, Chapter 28

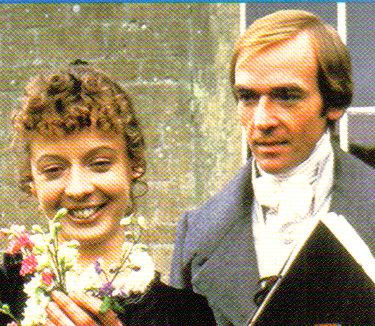

Elinor trying to get Marianne to compose herself (Irene Richards & Tracey Childs as Elinor & Marianne, 1981 BBC S&S)

“So you want to read Sense and Sensibility. Great choice! Jane Austen’s first published novel (1811) can get lost in the limelight of her other ‘darling child’ Pride and Prejudice, but is well worth the effort. There are many editions available in print today, and the text can stand on its own, but for those seeking a ‘friendlier’ version with notes and appendices, the question arises of how much supplemental material do you need, and is it helpful?

One option is the Oxford World Classics new revised edition of Sense and Sensibility that presents an interesting array of additional material that comfortably falls somewhere between just the text, and supplemental overload. This volume offers what I feel a good edition should be, an expansive introduction and detailed notes supporting the text in a clear, concise and friendly manner that the average reader can understand and enjoy.

The material opens with a one paragraph biography of the life of Jane Austen which seemed rather slim to this Austen enthusiast’s sensibility, and most certainly too short for a neophyte. The introduction quickly made up for it in both size and content at a whopping 33 pages! Wow, author Margaret Anne Doody does not disappoint, and it is easy to understand why after eighteen years publishers continue to use her excellent essay in subsequent editions … ”

I agree with Laurel that the 2008 reissue of the Oxford’s 2004 edition of Kinsley’s Sense and Sensibility is a good buy. It avoids extremes, or is a half-way house between series which just reproduce an unannotated text, only sometimes with a brief “Afterword” essay2; and series which may overload readers with an apparatus in the back of contemporary documents, recent critical essays (some the result of this year’s fashions in academia), and contain aggressive overly abstract introductions by writers who seem to take a downright hostile stance to the texts and most of its readers3.

The introductory essay by Margaret Anne Doody is brilliant, eloquent, and comprehensive; since 2004 the Oxford has included two appendices by Vivien Jones who wisely chose to explain two kinds of pivotal concerns and happenings in all Austen’s novels: Appendix One explains the rank and social status of the characters, and Appendix Two, the different dances included in her novels and how they can function. Claire Lamont has mostly improved on and rewritten the explanatory notes from the previous edition: the new ones are fuller, and more contemporary texts are cited. The method is to give the reference by page number and use an asterisk; this makes for a speedy flip back and forth4.

So much for complementarity. Laurel has summarized the topics of Doody’s introduction and interesting items cited in the bibliography, discussed the all-too-short life, and the role of chaperon in a young genteel woman’s life (as suggested by the appendix on dancing), and left to me the not unimportant business about exactly what is presented to us as Jane Austen’s written extant novel. To this I’ll add a little on the covers, and brief information on the 5 available film adaptations of the novel.

An anonymous crowd for a dance, Elinor and Willoughby unaware of whom they are dancing with (1995 Miramax S&S)

To wit, we do not have in whole or part any manuscript version by Austen of Sense and Sensibility so we cannot know for sure what her text of this novel was like. As they do today, printing houses then had styles of their own, and no text was at all sancro-sanct from changes in punctuation, grammar, paragraphing and the like. Of the versions of S&S published in Austen’s lifetime, the first published in 1811 was sold out. Austen rejoiced, and in 1813 there was a second. Austen was actively involved in the production of both; she proof-read the first, but, alas, apparently not the second, and errors of all sorts have been found in the 1813 text. On the other hand, Austen made small revisions of this 1813 text so those are her last emendations in print. Here we have to remember the painful truth that Jane Austen died young and didn’t have much chance to have second thoughts for her book: she was producing the final copies for all 4 she saw into print and writing all six (plus perhaps a seventh, Sanditon). A very busy lady indeed and then mortally ill.

Elinor (Joanna David) outwardly calm on her journey (1971 BBC S&S)

Elinor (Emma Thompon) writhing with grief at the apprehension of her loss of Marianne (1995 Miramax S&S)

Over the 19th century errors crept into the many reprints of Austen’s books; and in 1923 R.W. Chapman sat down to produce scrupulously accurate scholarly texts which were the equivalent of what were printed for very high status male authors; he followed the standards of his time, which included discreet corrections of grammar, punctuation and paragraphing. For Sense and Sensibility he chose the 1813 edition after correcting it, and it’s Chapman’s text that Kinsley studied, emended somewhat and is the basis for all Oxfords afterwards. Recently though it’s been asserted that Chapman over-corrected and so polished Austen’s text that we lose flavor, tone, and something of the colloquial voice of Austen; and in the 2003 new Penguin edition, Kathryn Sutherland has taken the rare step of using the 1811 text as her basis. Did Chapman really alter the spirit of Austen’s books? Yes and no. Sutherland’s edition gives us a less polished, more sparsely punctuated text.

It should be admitted, as with introductions to texts, this is something of an agenda fight. Kathryn Sutherland, Claudia Johnson (editor of the recent Norton edition), and others feel the perceived picturesqueness & tea-and-crumpets quaint feel of Chapman’s original Oxfords helped sustain a kitsch and elitist view of Austen. It’s also a turf fight: the publishers of these texts need their choices to be respected to gain the full Austen readership.

But there’s something more here too. Austen did change some actual wording in the 1813 edition. Now it’s sometimes true the author’s first text was the superior one; sometimes the last corrected one is. It’s a matter of judgement and taste. What’s important is the text be not bowdlerized. In 1813 Austen cut a second sentence that appears in the 1811 text: in 1811 at the Delaford Abbey picnic, the narrator repeats the rumor that Colonel Brandon has a “natural daughter” that Mrs Jennings’s brief mention made public. We are told Mrs Jenning’s statement so

“shocked the delicacy of Lady Middleton that in order to banish so improper a subject as the mention of a natural daughter, she actually took the trouble of saying something herself about the weather” (I:3).

Funnily, for all Sutherland complaints about Chapman, he did include the 1811 sentence in his reprint of the 1813 text. He simply intelligently made a judgement call and put it back. Alas, somewhere along the line this offending sentence was omitted from all editions strictly based on the 1813 text, and now appears only in the footnotes to all, including this latest 2008 Oxford! What bothers me is in the notes most scholars repeatedly refuse to recognize the obvious, that Austen deleted the sentence because it was too frank. Instead we get supersubtle interpretations that Austen removed the passage because she didn’t want the situation to be tactfully covered up. But how could it be, since Mrs Jennings has let the cat out of the bag, and this is one of those many secrets Austen’s Mr Knightley tells us is just the sort of thing everyone knows.

On to the covers. There is a long custom of picking pictures of two upper class women (often sisters) standing or sitting close together for the cover of S&S. This began in the first popular editions of the 19th century, Bentley’s 1833 volume where we see Lucy and Elinor walking together:

It’s seen in James Kinsley’s choice of a Hugh Thomson illustration of the very moment Marianne sees Willoughby at Lady Middleton’s assembly:

Entirely typical of just every choice I’ve seen is how Thomson’s psychological depiction is wholly inadequate. Pair after pair of women are chosen whose faces are expressionless, but whose credentials, as visibly upper class, fleshly (this once having been a sign of high rank), white, elegant dressers, are unassailable.

For example, Sara Coleridge with Edith May Warner by Edward Nash [1820], the 1980 Oxford cover; Ellen & Mary McIlvane by Thomas Sully [1834], the 2003 New Penguin cover.

These latest Oxfords differ only in preferring to focus on an enlarged detail of the two women, something Laurel tells me is fashionable in covers. An earlier version may be found in a 1983 Bantam:

Charlotte and Sarah Hardy by Thomas Lawrence (1801)

No one disputes the centrality of a pair of sisters as central to the novel (and primal to Austen as in all her novels we find them), but I am heterodox enough to declare that as a reader of Austen, I’m of the party who feels if we are to have two women, let us have either genuinely effective images, or one of the many effective stills from the recent movies, as in covers of the 1995 Signet and 1996 Everyman:

Emma Thompson and Kate Winslett as Elinor and Marianne Dashwood (1995 Miramax S&S)

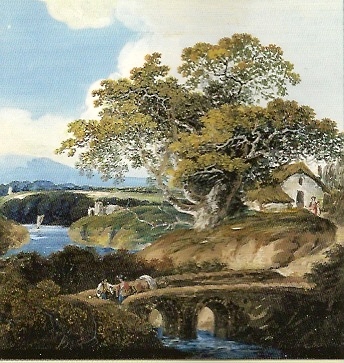

Or a landscape redolent of picturesqueness or some pivotal point in the story of the Dashwoods. The latter choice is uncommon; the 2002 Norton goes for this choice:

Devonshire Landscape by William Payne (c. 1780)

What I particularly liked about Margaret Doody’s essay in this new Oxford is she demonstrates the plot-design, climaxes, and much of the text of the novel is as much about social life, women’s relationship with other women, economic injustice, and aesthetic hypocrisies and affectation as it is a love story.

Marianne as a kind of Cassandra openly expressing outrage at the humiliation of her sister, Elinor, at a dinner party (1971 BBC S&S)

Which leads me to my last topic: the film adaptations, all of which are fine films in their own right despite their all being love stories, some of which reverse Austen’s thematic inferences, switch emphases, comment critically, or freely adapt. All enrichen our appreciation of aspects of Austen’s novel by bringing out elements in the text we might not have imagined fully or in this way for ourselves.

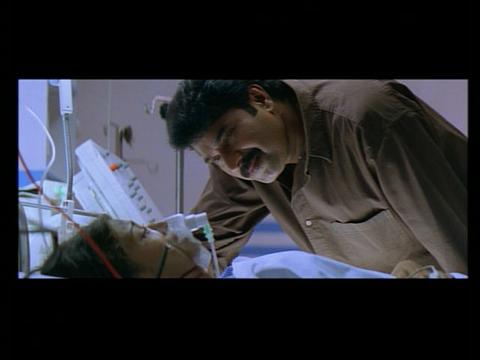

There are 5 available on DVD, all but one titled Sense and Sensibility: 1971 directed by David Giles, screenplay by Denis Constanduros, starring Joanna David as Elinor, Patricia Routledge as Mrs Jennings; 1981 directed by Rodney Bennet, screenplay by Alexander Baron, starring Irene Richards as Elinor, Diana Fairfax as Mrs Dashwood, Bosco Hogan as Edward; 1995 directed by Ang Lee, screenplay by Emma Thompson, starring Emma Thompson as Elinor, Kate Winslett as Marianne, Alan Rickman as Colonel Brandon, Hugh Grant as Edward; a 2000 I Have Found It directed and screenplay by Rajiv Menon, starring Mammootty as Captain Bala (Colonel Brandon), Aishwarya Rai as Meenu (Marianne), Tabu as Sowmyra (Elinor), and Ajith as Mano (Edward); and 2008 produced by Anne Pivcevic and screenplay by Andrew Davies, starring Hattie Morahan as Elinor, Charity Wakefield as Marianne, Janet McTeer as Mrs Dashwood, David Morrissey as Colonel Brandon, Dan Stevens as Edward, Dominic Cooper as Willoughby5.

Elinor and Edward retrieve the precious possiblity of spending their lives together (Hattie Morahan and Dan Steevens, 2008 BBC/WBGH S&S

In my judgement the 1971 film is a quiet delicate drawing-room comedy which interestingly anticipates many of the elements of the films to come; it shares with the others a reading of the book which people can discuss with others. The four later ones all add perceptive modern interpretations, visual and sensual landscape splendor, and fascinating psychological story-telling, not to omit (in the 2008 film) cogent commentary on the novel different from Austen’s, and (in the case of Menon’s film) a particular different cultural tradition than Austen’s.

Ang Lee & Emma Thompson’s S&S is the filmic masterpiece of the group:

The exhilarating sunlit drive of Willoughby (Gregg Wise) and Marianne through the countryside (1995 Miramax S&S),

though it departed by making Brandon the hero, for an iconic scene:

Willoughby (a startled Greg Wise) rescues a clinging lest-she-fall Marianne (Kate Winslet)

is displaced by another true romantic hero:

Colonel Brandon (an uncomfortable-looking Alan Rickman) hoists an apparently somnolent Marianne (Kate Winslet).

But there is much to be said for the 1981 melodrama: it’s much better than is usually acknowledged, and influenced the ‘95 film; the love of Edward and Elinor is presented as both intense and delicate:

Edward (Bosco Hogan) holding Elinor’s (Irene Richards) sketch book (1981 BBC S&S)

Andrew Davies’ is, by contrast, a humane masculinist take on the novel. Davies is the only film-maker of S&S thus far to have dramatized the duel:

Brandon (David Morrisey) duelling to kill Willoughby

The scene alternates with Marianne (Charity Wakefield) writing her last letter to Willoughby, and thus changes the atmosphere from one of two sisters struggling together utterly

I have an idea I have Found It is not sufficiently well-known, and fellow Austen readers, if you do not see it, you will have missed a moving and stunningly well-danced recreation in contemporary as well as Indian terms of this great book.

Sowmyra-Elinor (Tabu) dances with Mano-Edward (Ajith) (2001 I Have Found It)

The John and Fanny Dashwood of the piece discussing how little they can give the sisters and mother

Iconic image of Meenu’s [Marianne] encounter with death this time in lieu of Elinor-Sowmyra, the melancholy Captain Bala [Brandon] hovers over Meenu [Marianne] (Rai & Mammotty, 2000 I have Found It)

See also for more comparative stills, The Poetry of the S&S movies_, Similarities and Absences in S&S films, Landscape Altered.

Next up: the new Oxford Pride and Prejudice.

Ellen

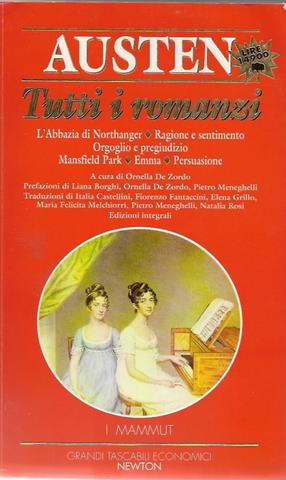

1 In 1997 David Gibson in his monumental A Bibliography of Jane Austen (Delaware: Oak Knoll Press) catalogued 249 different editions of Austen in various languages from the very earliest to date, from the familiar European languages, to languages as diverse as Russian and Japanese, and as diverse as Tamil and Serbo-Croat. For Sense and Sensibility I own Jane Austen, Raison et Sentiments, trans. Jean Privat, note biographique de Jacques Roubaud. Paris: Christian Bourgeois 1979; and Ragione e sentimento, trans.Fiorenzo Fantaccini, introd. Pietro Meneghelli, in Jane Austen: Tutti e romanzi, ed. Ornella de Zordo (Rome: Grandi Tascabili Economici Newton 1997.

2 I qualify: Patricia Meyer Spacks’s afterword in the 1983 Bantam edition of Sense and Sensibility, though too short for enough development, is one of the best essays I’ve ever read on the novel. The faithful lover of good Austen sequels will know the cover is the one that appears on the second edition of Diana Birchall’s Mrs Darcy’s Dilemma.

3 Another qualification: There is nothing better the curious reader who wants to understand Austen and her book can buy relatively inexpensively than the Broadview edition of S&S by Kathleen James-Cavan, with her sympathetic perceptive introduction situating Austen’s books amid other novels by contemporary women, choice of regency texts on sensibility and the picturesque, reprints of the poems Marianne alludes to, drawings of carriages, and a map of London at the time.

4 The other method is to use superscript numbers in the text, grouped discretely for each individual chapter. The superscript method may be easier to follow but the latest Penguin (2003) which follows this, has cut the notes from the previous (compare the 1995 edition), so you get much less needed information. I here commend the Everyman people for in their run of editions, they include a handy and detailed chronology of events in the era (“historical”), alongside events in Austen’s life and births, deaths, and publications by other writers. See Sense and Sensibility, introd. Peter Conrad (NY: Knopf, 1992). No 51 in new Everyman series.

5 I have listed those actors who both played an important role in the film and whose career continued to be important after it, or where there are interesting connections with other Austen films. Ann Pivevic is also the producer of Miss Austen Regrets, and the films use similar cinematographic techniques and show a similar take on Austen herself.

Marianne (Ciaran Madden) in the 71 BBC S&S: “I should hardly call her a lively girl—she is very earnest, very eager in all she does—sometimes talks a great deal and always with animation—but she is not often really merry (Austen, S&S, 1:17).

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I want also to write a little more about the new Penguin edition by Kathryn Sutherland: besides reprinting the 1811 text, this edition reprints one of the great essays on S&S: Tony Tanner’s. Herewith a redaction of this:

Tanner says S&S is a book which meditates the demand for secrecy in society and reveals the sicknesses and miseries such secrecy encourages and allows. He presents the need the individual has to keep her inner life secret as a necessary guard against the viciousness, stupidity, competition, materialism, and exploitation other people will inflict on anyone who shows their more vulnerable sides. He shows how such secrecy twists people; how it becomes a weapon in the hands of the unscrupulous. He goes through many scenes where this word is used or its idea embodied in many varied forms, and connects secrecy to the necessity of lying, to the pains this inflicts.

He also connects it to the use of screens in the book—Elinor is a screen painter. He brings out the period’s sense of itself as one in which people for the first time were willing to admit to or at least described “nervous disorders.” He also shows that screen-painting, secrecy when practiced on behalf of others can also be forms of sympathy, of care, of concern, and demand great strength.

I have always looked at Elinor and Marianne as a doppelganger figure which examines the sexual longings of women; this can be seen as just one phase of this larger perspective Tanner puts on the paired heroines. Secrecy and sickness widen out to the larger issues of “jostling for partners, property, and power” which the plot line embodies.

Since he is so moved, goes with the grain of the book, and stays with the text to bring out all sorts of important perceptions about our lives, he again and again waxes eloquent. I will quote just a few lines and passages which are filled with good thought and imagination:

1) I like his definition of sensibility as “a fineness of feeling and disposition which took one out of the arena of more brutal abrasive appetites and desires which constituted ‘the world’ and or society at large…”

2) how “the opportunistic marriages” of the book “provide suitable punishments in the form of domestic misery…”

3) the long section describing the mounting tension between Elinor and Marianne as each practices a game of concealment in front of the other (pp. 80) which culminates in Elinor’s outburst: “For four months, Marianne, I have had all this hanging on my mind, without being at liberty to speak of it to a single creature…”

4) Marianne’s deep illness as a form of near suicide linked up to Foucault’s ideas about madness in a repressed society (pp. 82-3);

5) I thought he was very good on how little we know about the people we spend hours sitting next to (never mind people on a list), and other the presence of other people often coerces us into destroying parts of ourselves while we are with them (pp. 86-8);

6) he’s right about Austen’s society being one which “forced people to be at once very sociable and very private,” and I thought the paradox that “interior freedom amounts to interior distress” (if you have nothing to control your thoughts you will go deeper and deeper into misery, madness, loss of perspective) well taken

7) the idea that the effort to make words coincide with things and screen us is done in order to provide us with a measure of dignity and peace (p. 93);

8) when he turns to sex in the book his language sings: Marianne is “interested in the more primitive, even the more Dionysiac man.” She is the one who loves movement, wildness, dance, the wind, the leaves; “Elinor has an instinct for stillness and composure.” (p. 97)

9) Finally he is right to bring in Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents as mediating one of the themes of this book.

This essay is criticism at its best when confronted with a serious and great piece of art in the novel form and when it proceeds from the assumptions that what makes a work of art great is its ability to illuminate the private and social structuring of our lives.

Tanner writes so superbly on this novel is that it answers his demand a book have deep and important truths about life—as he understands it. He clearly prefers the less comic and more grave aspects of Austen. A give-away of his attitude may be found on where he compares Marianne’s illness to “the amazing burlesque on excessive sensibility to be found in such pieces as Love and Friendship. It’s clear he thinks S&S is much superior to this earlier juvenilia because it tells its truths through sequences which verge on the tragic and are presented with deep emotional seriousness.

Tanner is also very good on MP, another book he finds deeply congenial.

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 1, 11:45pm # - N.B. “Ours is a competitive business, sir” is a quotation from Dickens’s Christmas Carol. I use it ironically. In Dickens’s story, the ghost of Christmas Future takes Scrooge to see his house as he lays dying (in the future). Scrooge and the ghost stand and watch people stealing Scrooge's curtains and ransacking his house. Scrooge notices a man in black who appears to be doing something with or standing near the dying man on the bed. Scrooge understands that he is an undertaker, and tell him he (Scrooge in future) is not yet dead—or something to this effect. The man replies: “Ours is a competitive business, sir.”

The Jane Austen editions are a competitive business. I am ironic.

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 2, 12:35am # - These entries in your blog have had the effect of spurring me to purchase the Norton and Penguin editions!

— Jill Jul 3, 9:58am # - My friend, Jill, also sent me this about the Norton, and asked me what I thought about it:

“By Jack Cade (Mass. USA) – See all my reviews. Sense and Sensibility is a work of wit intelligence and genius: the critical apparatus and here I mean the work of modern critics is the work of those “favored” by stupidity. With the exception of Raymond Williams important article from “Keywords”—the critics are informed by a feminism that might be called Sexual Stalinism. Critics with agendas are always reductive, unreflective and in the case of one essay unpardonably vulgar. I name no names. William Empson’s exploration of ‘Sense, ‘Sensibility,’ ‘Candour,’ and ‘Candid,’ which are briliantly investigated in his Structure of Complex Words apparenty was not deemed worthy of making the cut. Jane Austen would have had a good laugh had she read the sanctimonious essays that befoul this edition. If you are a good reader trust your own responses and get another edition. Of course if you are a member of the academy this edition is indispensable.”

Several critics (P.J.M. Scott, Perkins, Tanner) have suggested S&S is Austen’s most radical book. It’s also strongly feminist because the victims are women. The paradigm is that found in Montolieu’s 1785 Caroline de Lichtfield, which Austen read: in CL the Brandon character is a cripple whom the heroine is married to early in the novel and for most it refuses to have sex with. This paradigm is still with us and can be found in genius form in Wharton’s Summer: the Marianne is seduced, impregnated, & abandoned by the Willoughby character; he marries a wealthy woman. In Wharton's version the young heroine must marry the Brandon character, and we are to feel his age is distasteful to her for real; the last scene is of her as a pregnant wife walking slowly up the stairs to have sex with a man she is reluctant to have sex with. Austen's Brandon tells us his brother who Eliza Williams was forced to marry had "pleasures" he should not have had, and the sense of the sentence is (beyond his unfaithfulness and gambling) that he inflicted on the young wife distasteful forms of sex. All are strongly feminist.

Anyone reading S&S sees it unless they try to erase the gender aspect by talking universally. Tanner does; Raymond Williams is of the pre-feminist school. So Cade excepts Williams. Basically he either misreads (or he would hate the book), and so blames the critics, but being devious, more than a little dumb, and hypocritical (Cade probably hates pessimism too) doesn’t admit or even realize that.

It is true that Claudia Johnson’s Norton contains more feminist and scholarly essays than any other; she has essays which show how the novel through its displaced and coerced women and younger sons critique property arrangements; John Dashwood’s behavior is that of a person pushing tenants off property and enclosing property. I’ll bet Cade dislikes that too; it’s what he calls sanctimonious. Using the term “politically correct” is now recognized to be bad-mouthing, so he calls them “sanctimonious.”

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 3, 10:42am # - In response to Jill,

It depends what you want: the new Penguin for the first time ever reprints the 1811 text and it is different; it includes the Tanner essay. The Broadview (editor Kathleen James-Cavan) is excellent for its (otherwise hard to get) contemporary documents about sense, sensibility, picturesquesness, maps, contemporary reviews. So you picked the ones I would have recommended!

I’m not sure one should buy an edition for the introduction or I’d say try to find the Bantam with Patricia Meyer Spacks’s essay or buy this new Oxford with Margaret Doody’s, the appendices about dancing and rank, and full notes. The new Oxford does have and 1813 text as edited by Kinsley using Chapman (and where the offending sentence has been pulled and is in the notes).

Ellen

— Elinor Jul 3, 10:54am # - Reader, I’ve bought the Broadview edition. I thought you might be interested in this excerpt of Melvin Pena’s Amazon review of the Broadview edition:

Jane Austen’s 1811 novel, her first published, “Sense and Sensibility,” receives a grand treatment in this Broadview Literary Texts edition, edited by Kathleen James-Cavan. Anyone who knows me knows how I doat on Jane Austen, and for the first time reading her in a Broadview edition, I find myself doating excessively. “Sense and Sensibility” was the first public exposure of Austen’s masterful characterization, plotting, and satire to reach the reading public of the Romantic Era. Austen thrives on what I like to call ‘the middle of the book,’ writing the situations that complicate the lives of her characters, better than almost anyone – almost, it seems, preferring getting her characters and readers in a position to learn from their mistakes, than actually getting them out.

[...]

I’ve praised James-Cavan’s handling of this Broadview edition, and now may be a good time to say some more on that head. Broadview and its editors, like the people who put together the Norton Critical Editions, concern themselves with really presenting literary texts in a solid foundation of cultural, theoretical, and critical contexts. “Sense and Sensibility” contains a real treasure trove of such material – the two contemporary reviews of Austen’s novel from 1812, generous selections of essays from the late 1700’s and early 1800’s on contemporary debates on the meanings of the words “sense” and “sensibility,” and on the cult of sensibility and the picturesque. Also included are exerpts from poems referenced by Marianne throughout the novel, illustrations of the vehicles they travel in, and a map of the character’s London residences. James-Cavan’s excellent introduction also lays out the novel’s issues in their contemporary, cultural, critical, and theoretical contexts, none more obtrusive than any other, and all quite helpful. Altogether, the Broadview “Sense and Sensibility” is a tremendous edition for Austen scholars and casual Janeites alike.

[end of excerpt]

For the complete review, go to Amazon.com.

I enjoyed Pena’s insightful review, and play to see what else he has reviewed. Query; I assume “doat” is the archaic spelling? It reminds me of JA’s “freinds”.

— Jill Jul 3, 11:47am # - This Melvin Pena is a very interesting person. 15 pages of reviews on Amazon.com, almost all very highly rated. On the first page he reviewed two CDs (from one: ), The Last Unicorn: (40th Anniversary Edition) by Peter S. Beagle,Pere Goriot by Honore de Balzac, Dune Messiah (Dune Chronicles, Book 2) by Frank Herbert, Heartbreak House (Penguin Classics) by George Bernard Shaw, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Penguin Classics) by James Joyce, Treatise of Man (Great Minds Series) by Rene Descartes, Dune (Dune Chronicles, Book 1) by Frank Herbert, The Man of Feeling (Oxford World’s Classics) by Henry Mackenzie, and The Man of Feeling (Oxford World’s Classics) by Henry Mackenzie. He must be young (at least compared to me!) because he quotes the movies “The Neverending Story” and “The Last Unicorn” as favorites during his childhood. So he must be approximately the same age as my own children, who also loved these movies.

— Jill Jul 3, 12:04pm # - I had some issues with the Ang Lee film version. When I first heard that Hugh Grant starred in it, my first reaction was: “What a wonderfully rakish Willoughby he will make!” No, he was cast as good ole Edward instead. For me that was a major letdown. And Emma Thompson is a great actress, but she was 20 years too old to play Elinor, who is still a teenager. Kate Winslet and Alan Rickman were wonderful, though.

Beyond the casting issues, I thought Emma Thompson’s (award-winning, by the way) screenplay laid it really thick on the post-feminist side. No subtlety there.

And more generally I am turned off by Jane Austen adaptations that rely on gross visual humor. In this S&S we had the horse dung, and the latest P&P (the one with Keira Knightley) treated us to a close-up of pig genitals. So very unAustenien in both cases!

But that’s just me. I tend to be very protective when it comes to Jane. I still liked Ang Lee's S&S far better than the latest P&P.

— Catherine Delors Jul 3, 3:08pm # - From Diana:

“Much enjoyed your reflective blog on the new Oxford edition, Ellen. I am

also in league with your congeners, Ms. Place and Laurel Ann, developing a cunning new romp with Mrs. Elton. Those young ladies have a very great deal of imagination.

Diana Birchall”

— Elinor Jul 4, 11:01am #

commenting closed for this article