Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

David Auburn's _Lake House_, a free adaptation of Austen's _Persuasion_ · 15 July 08

Dear Friends,

Thanks to the kindness of Marilyn on Austen-l, I’ve found another free adaptation of an Austen novel! In 2006, The Lake House, directed by Alejandro Agresti, screenplay David Auburn, produced by Doug Davison (Warner Bros product) was shaped to be a commentary and adaptation in modern terms of Jane Austen’s Persuasion.

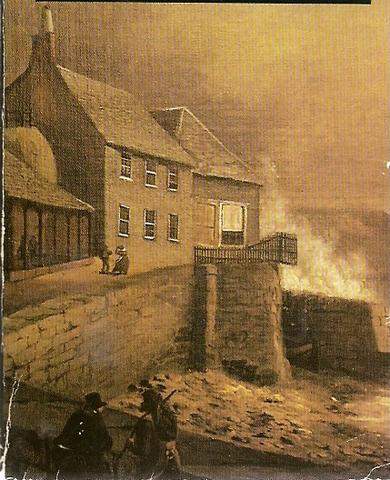

First, it has all the marks of the species. Early in the action of the movie, the book is brought up explicitly and a copy put before the audience. In Lake House, the heroine, Kate Forster (played by Sandra Bullock) leaves a mark of her presence for the hero, Alex Wyler (Keanu Reeves) to find: it’s a copy of Persuasion which Kate had forgotten (perhaps her father had given her it as a present), and left on railway station waiting area bench. He finds it. It’s the very Norton edition whose lovely picturesque illustration of Bath I’ve put on this blog! Then a little later in another encounter Kate tells Alex that Persuasion is her favorite novel, and she explicates it in such a way that it becomes an analogy of what’s happening in the film. Persuasion, she says, is a novel about “waiting,”, two people meet, fall in love, the time is not right, and they are parted, but years later they get another chance.

Kate (Sandra Bullock) tells Alex (Keanu Reeves) Persuasion is her favorite book, explains the meaning of the novel as she understands it

Another much older battered copy of Persuasion is found in yet a third incident, and this time the point is made that in our present story, it is too late to make the chance encounter work. It won’t do. You cannot retrieve time. Finally, at another point in the film, the heroine reads aloud a moving passage from early in the novel when Anne is in her nadir of loss and remembers how as opposed to the indifference she feels from Wentworth now, what once they were together (two souls could not have been more in unison).

Three free adaptations I’ll instance raise the same sort of flags: Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan, Ephron’s You’ve Got Mail, and Victor Nunez’s Ruby in Paradise all have the book in front of us explicitly; have discussions of it, and quote from it. Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Dairy takes over core characters too

The reason there are so many references is the outline of the story is more distanced from Austen’s Persuasion than most of these free adaptations allow (though the same distance occurs between Northanger Abbey and Ruby in Paradise), and this is not just a recreation in modern terms, but it departs from the original ending; indeed it reverses it. Austen’s Persuasion ends in retrieved joy amid much duress and an existence where the two are surrounded by continual anxiety, discord, irony (Mrs Clay may yet be Lady Elliot); in Lake House, many of these negatives are there, and the couple do not manage to get together after all. They come near a few times, but these are fleeting encounters.

On one level, the film suggests the fantasy or fairy tale element of Austen’s book. Lake House is an open fantasy. Alex Wyler and Kate Forster are in two different time zones and communicate through letter writing in an old postbox in front of a lake house.

Alex and Kate by their post box in a wintry landscape

Alex has come to live there now which for him is 2006; the heroine just moved out which for her is 2004. As the movie opens, we see her leaving, and then seconds later he moves in. She had left something behind and writes to him from nearby Chicago to ask him to forward it. He replies he sees nothing of what she speaks, but will look for it; he remarks the house clearly has not been occupied for a long time; she denies this and say she thinks someone (him) moved in after her. That begins the communication which is kept up through putting letters in a old mailbox in front of the lake house.

So the epistolary nature or foregrounding of Austen’s art is part of the movie. Letters as a way of communicating also give Auburn a chance to have some funny allusions. For example, the heroine’s mother (Willeke van Ammelrooy) who in her common sense and closeness resembles Lady Russell as a confidant says to her daughter why spend all this time with fantasy, and rermarks he must be a “helluva letter writer.” Kate may say something like yes, “There was one especially …. ” (or words to this effect). YOu see the sweet joke if you remember Wentworth’s great letter.

The movie in effect tells us that a tragedy underlies the reality that Austen’s Persuasion plays upon, for in Lake House we find that the deeply longed-for union is improbable.

Alex has not showed; Kate left alone

The hero and heroine would not have gotten together, for death would have intervened. The movie thus insists on the presence of death in Persuasion—and it is accurate here. People may recall how at dinner at the Musgrave’s Captain Wentworth says he almost went down in the Ash, that is brought into the film and the hero does go down (I won’t tell how). Here is the cover of my favorite much-battered edition of Persuasion:

1965 Penguin (my battered much-read favorite copy)

Moments in the film (which takes place on a lake—lots of water in Persuasion) seem to remember the closing paragraph in the novel which shows Anne’s nervousness lest she lose her beautiful captain once again, to death. Baggage, the baggage of parents, the hero has a hard father (Christopher Plummer plays the part) who was deeply unkind to his wife, self-centered, hard—as we are told the one mistake Lady Elliot made in life was who she married); the hero has a brother, Henry (Ebon Moss-Bachrach) who is his confidant—rather like Wentworth has his group of friends. The heroine, Kate, is all alone, isolated but for the mother (who is now divorced).

The reader should know there is an intervening text. As with You’ve Got Mail whose literal story is based on a movie called The Little Shop Around the Corner, so Lake House is also an adaptation of a South Korean film called Il Mare. On Austen-l, Marilyn said of this “It’s a very sweet story (the hero calls the house Il Mare because it’s on the sea), but that film has no Austen associations.”

I was struck by how much the male point of view came through in Lake House even if Kate played Wentworth’s role partly. Persuasion is told from Anne Elliot’s point of view and not until the near final scene do we hear how Wentworth felt from his own lips and his journey from hurt to resentment to awareness he still loves her and so on. (The same thing happens in P&P where Darcy is kept from us.) Again this is common among the Austen adaptations where a woman-centered story becomes equally male-centered or more interested in the hero (the 1995 P&P by Andrew Davies comes to mind) than the heroines.

Lake House highly romantic as are so many of the Austen films. The film-makers clearly believe that romance sells. But Austen’s romance is highly compromised or tenuous—which is also why her books for moving. Southam in his excellent book on JA’s brother and the Navy and the three later novels says danger is the reality and death was common (so William Price is at risk). There is much irony in the ending of Persuasion: that is, Mrs Clay if she plays her cards right, and it seems she is, will end up Lady Elliot. So much for Lady Russell’s dreams. Poetic justice I suppose when you consider Sir Walter and Elizabeth. Wentworth’s good friends do not live well and one is in bad health. Benwick’s marriage. Right now they’re euphoric, but as Wentworth’s comment revealed, this is a marriage which may well end up as so many in Austen: the intelligent man married to the dull woman, charmed by her physical presence, liveliness, and sheer need.

Through using a tragic thwarted fantasy using much nostalgic techniques (the music, the montage), The Lake House recreates and comments on the actual mood of Persuasion. By contrast, the 2008 commentary film turned to abjectness (for both hero and heroine) and the motif of post-feminist retreat to convey this.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Marilyn:

“Ellen, I’m glad you enjoyed this film. It was a great discovery!

The Korean original “Il Mare” is impossible to rent, so I forked out the $11 at deepdiscountdvd. It’s a very sweet story (the hero calls the house Il Mare because it’s on the sea), but that film has no Austen associations.

A driving force in both films is the attempt to not create a paradox in time—if he dies, as a result of some misdirection given to him by her, then the correspondence didn’t happen and the love never happened and she can’t save him from dying, etc. Some key episodes happen before the correspondence begins, so she is unaware of their vital importance and may not act appropriately. The Korean version takes things a step further: she leaves a fish in the mailbox, so he has a fish that hasn’t been born yet. The dog, who plays an interesting role, never personally experiences an interruption in his timeline, but he is a vital link between the two times and the two lovers.

All this folderol about time, in contemplation of Anne and Frederick’s plight, adds an other-wordly aspect to their relationship. It creates a feeling of such profundity about their union that, if they don’t resolve the timing issue, they will each suffer a lifetime of great sorrow and regret. This sense of urgency is in the book—Frederick and Anne belong together, but they have to rise up to the challenge and battle the forces working to keep them apart or they will suffer the same sad fate. Austen informs us of the sorrow and regret that make up Anne’s world; we can only imagine Frederick’s state of mind during those long years at sea.

I think David Auburn deserves credit for finding the heart of the book and restating it in an independent format. My hat’s off to him.

Ellen’s comment about the “presence of death” resonates. In both films, the man’s death comes about as a result of the heroine’s error. One large difference is that in Il Mare she doesn’t know him yet when she witnesses his death and later makes the connection that he died at her direction and this is what she must correct. In Lake House, Kate is a doctor and, witnessing his accident, runs to help but he loses his life despite her efforts. It’s the depression that she feels after his death that sparks her journey to the Lake House. When Kate realizes that she must stop him from going to his death, it is doubly poignant because she has already let him irretrievably slip through her fingers.

[This also creates a paradox in time: logically, if she stops him from dying, she won’t be so depressed by her failure to save a stranger that she rents a lake house, and all of the subsequent action.]

It is interesting to see Persuasion through a man's eyes. Written so strongly from Anne's point of view, we forget that Frederick suffered as well. Her mistake leads him to the brink of the abyss. His long seafaring voyages and naval battles were a descent into the pit of hell; somehow he managed to survive the horrors of war and the loneliness to return to her side. Lake House repeats that voyage – her thoughtlessness sends him to his death. The question is whether Kate can stop him in time to avoid death—and in Persuasion whether Anne can pull him back into the light.

The question to me is whether Jane Austen was aware of her approaching death when she wrote this book.

Next assignment: how much of Emma is in Proof?”

— Elinor Jul 15, 1:26pm # - First I thank Marilyn for her thoughtful lively replies. Offlist someone told me about the intervening source I’ll call it—in You’ve Got Mail we have the same thing: the movie is based in its plot-design on The Little Shop Around the Corner, but it’s been transformed and also the central characters reshaped to re-enact aspects of P&P. An interesting thing here is how often when material is “Austenized” the story uses epistolarity whether through letters (as in Lake House) or emails (as in You’ve Got Mail). A number of the movies blend female narrators with clever uses of epistolarity (flashbacks melding into flashbacks, voice over and so on).

I was struck by how much the male point of view came through in Lake House. Persuasion is told from Anne’s point of view and not until the near final scene do we hear how Wentworth felt from his own lips and his journey from hurt to resentment to awareness he still loves her and so on. (The same thing happens in P&P where Darcy is kept from us.)

Marilyn mentioned Proof. I went over to IDMB and discovered it—I’d never heard of it before, another one by David Auburn. Young women gives up her life for a while to care for aging father. And Gweneth Paltrow who played Emma in the 1996 Miramax movie. Both the play Proof and movie are given strong positive reviews. Shall I rent and watch it? Do you mean to say it too is a free adaptation, or is it more in the vein of alluding to Austen’s book (as say I Capture the Castle alludes to Austen’s books).

Ellen

— Elinor Jul 15, 1:27pm # - From Jeanne Lugo:

“Perhaps the best explanation of what Persuasion is about as any I’ve heard. I think it’s no coincidence that younger people tend to call P&P their favorite, but older (er, “mature”!) persons tend to call Persuasion their favorite. We have lived enough to have regrets, some of them piercing, and in some cases we know the pain of having made a bad choice. Persuasion promises that the most tragic of our choices (the ones that cause us the greatest grief) can be made right. It’s much more “fairy tale” and “romantic” than P&P could ever hope to be. P&P is about the rather prosaic desire to find a quality mate—but P is about regrets made right, about “retrieved joy”, a much rarer kind of bliss.

BTW, I loved The Lake House. Of course it’s not a P adaptation. But it has the same running themes—loneliness, passion subdued, sorrow,heartbreak, loss, hope and finally “retrieved joy”. It is one of the most yearning films I’ve seen in decades—some of the scenes with Sandra Bullock looking out a window, or into the middle distance are so filled with sadness and yearning that I feel the pain of it in my own throat. I think one reason why too many don’t see it as a _P_ adaptation, and perhaps don’t like it at all, is it’s the WOMAN who is in the Wentworth position. She is the one who feels betrayed by the choices of her lover (in this case, when he doesn’t show up for appointed rendezvous at the restaurant), and she is the one who abruptly cuts him off and tries to live her life without him. He is the one in the position of waiting—for her to figure out that he was not malicious in his not meeting her, and finally, having to wait years, many years, for her to be “ready” to see him. (I am being purposefully vague here, in case others want to see the movie). I think too many Janeites, and movie goers alike, can’t accept a woman in the dominant position, can’t accept her being stupid enough to throw over heartfelt love (men are supposed to be that foolish, not women!).

Jeannie Lugo”

— Elinor Jul 15, 1:29pm # - From Angie:

“Now I haven’t seen this movie, but I distinctly remember when it was

released and I remember reading about the connection to Persuasion,

which I believe it was intentional not just some vague similarity.

Angie”

— Elinor Jul 15, 1:29pm # - Laura Carroll:

“I’m afraid I can’t support this with detailed reasoning, but the Ang Lee film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon reminded me very strongly of the structure and mood of Persuasion. It’s a romance between a couple who were separated by war and it’s centred on the consciousness of the woman, who has been in private mourning since the breach, and the real extent of her merits are not recognised by anyone except the man.There is a reconciliation but its ending is more tragic than Persuasion’s.

Laura”

— Elinor Jul 15, 1:31pm # - Elissa:

“I think Ellen has “hit the target” in recognizing the somewhat elegiac mood of Persuasion [currently favorite of JA’s novels; but that is probably because I’ve read it most recently]. If this novel were a piece of music, I’d say it were written in a minor key – say E minor [Beethoven’s piano sonata 27 was in E minor; the “Appasionata” sonata written in F minor; and the glorious Fifth Symphony in C minor] to illustrate the depths of disappointment, hurt, despair, and sadness involved in human relations in the real world. It reflects a totally different sensibility than the brighter, more “gilded” and fairy-tale happy ending world of P&P.

Although I haven’t seen The Lake House, like my good friend Lady Catherine de B., I deem myself most proficient to make a critical judgment here: four visual references to a particular book is strongly calling the viewer’s attention to it – and not in a nuanced way. Whether the filmmaker succeeds in weaving the story as a Persuasion variant is another matter. ”

— Elinor Jul 15, 1:31pm # - I’ve seen The Lake House twice and liked it very much – I noticed the references to Persuasion, but hadn’t drawn out all the similarities beyond that, so am very interested to read your review and now thinking I will have to watch it again bearing your insights in mind. It seems as if there are far more movies than I’d realised which are free adaptations of classics. I’ve also seen Proof;, but don’t remember noticing any similarities with Emma; the plots are not similar on the surface, anyway – so maybe I should watch that one again too…

— Judy Jul 15, 2:58pm # - From Jerry Schurman on Austen-l:

“Okay, after a glance through the [Austen-l] archives, it appears that we know that Lake House is based on Il Mare, but there has been no mention of its source material in turn, La Jetee, a famous montage which (its director, Chris Marker, says) was inspired in turn by Vertigo, and which is the basis for Terry Gilliam’s Twelve Monkeys.

Also, a movie that is very deserving of mention in this conversation about film, grief, and separation is Truly, Madly, Deeply. Not only is it full of Alan Rickman’s beautiful deep voice, but also his character plays its musical counterpart, the cello. I haven’t seen this movie since it came out eighteen years ago (ack!) but I remember it being very beautiful.

Despite its superficial commonality with Persuasion and The Lake House, I view Truly, Madly, Deeply as the opposite story. Here the second chance fantasy is what ultimately allows grief to be resolved by letting go and continuing to move forward in life: the reality of the second chance can not match the grief-stricken wish of what it would be. It is tempting to treat Jamie[the male lead]’s death and supernatural return as dramatizing the rooted-in-reality scenario of a breakup followed by trying to renew the relationship.

Even _P_ acknowledges this point: the book says early on that Anne’s terrible loneliness and isolation are partly because nothing/nobody came her way after Wentworth, and a theme of the book is that the world of difference between the travel and action of men’s lives and the circumstances of women’s lives have cruel emotional consequences: “We live at home, quiet, confined, and our feelings prey upon us,” says Anne to Wentworth, albeit indirectly. Anne has had to endure eight years without the opportunity to work through (“process” in psychobabble, I suppose) her grief.

Jerry”

— Elinor Jul 16, 6:19am # - Thank you very much to Jerry. I keep meaning to rent Truly, Madly, Deeply. Now I have it down with Proof for my next visit to our local DVD, video store (one in Old Town, Alexandria, which has a fine selection of films). Actors and actresses carry psychological baggage from role to role and to see Rickman here will also resonate with the 95 S&S as Emma Thompson in Howard’s End resonated (more than resonated, the scripts are consonant and the earlier film influenced the later).

Which gets me to my second point: You’ve got Mail is reshaped to be a very free adaptation of P&P though (apparently like Lake House), its ultimate plot-design comes from another movie, in this case The Little Shop Around the Corner. Now if you look in The LIttle Shop you discover it has a previous antecedent (in a stage play I recall, but memory is treacherous …). There’s a book much worth reading which argues that much that we see is adaptation, and that originality is not just a falsifying fetish, but to hold to it skews our appreciation of much that we enjoy and how art works are interconnected: Linda Hutcheon’s Theory of Adaptation. I remarked I’m going to see four operas in August: they are all ultimately adaptations of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, but each also follows the laws of its particular subgenre (say musical comedy for Kiss Me Kate), the conventions of its era (the Wagner MforM and Bellini’s Romeo and Juliet). I do recommend Hutcheon for your perusal, Jerry.

The key though to proving close adherence in which a particular work is really meant to be recreated is that the film-maker or author or artist 1) closely aligns some idiosyncratic things found in both works, the early and the late; and 2) in the case of modern movies, they explicitly bring the earlier work up and even discuss it. That’s the case with Ruby in Paradise (for NA), Metropolitan (for MP), Lake House (for Persuasion), You’ve got Mail (for P&P). Now some movies can get along without this: say I Have Found It for S&S; there there is an almost rigid adherence to certain turning points in the original S&S transposed to I have found it, the Indian names are assonant with the English ones (Bala for Colonel Brandon, Meenu for Marianne). Movies also avail themselves of hiring the same actor (Colin Firth for Mark Darcy, Kate Beckinsale repeatedly for Emma-like parts in movies which are not remakes of Austen but do allude to her, as in Cold Comfort Farm).

Cheers to all,

Ellen

— Elinor Jul 16, 6:59am # - On Janeites, Catriona wrote:

“One of the most wonderful things about Persuasion is that it investigates what really matters in the competing needs for status, power, money and love in their various forms. It is an adult novel because you need adulthood to engage with it.

‘Retrieved joy’ is a fitting description and I don’t despair for Louisa and Benwick, she has been able to respond to his need generously and is already developing in the literary direction. Theirs may not be the greatest love of all time but that still leaves room for a very satisfactory one.

Catriona”

To which I replied:

Well yes Catriona, but is it really a case of a half-full glass being declared half-empty? Austen’s emphases throughout her novels have been on couples (repeatedly this motif) where the man is a much more intelligent or capable thinking person who marries a silly wife, and then after the euphoria of the initial stages of marriage are over (which we rarely see and we don’t even see it in Benwick and Louisa, are only told of it), he loses respect for her and himself for having married her, and spends the rest of his life reacting to her eccentrically or counterproductively, for after all one person cannot change another and in this era divorce was not possible.

The emphasis in the conversation between Wentworth and Anne is Wentworth’s awareness of disparity and if not so much worry for his friend, inability to understand how a man can make such a choice. Like Mr Knightley apparently, Wentworth thinks men are not attracted to silly wives. He discounts sexual attraction and excited emotionalisms, both of which hit him at first in Louisa’s case, but were not what would or could drive him to propose to her. We are also shown that he was still feeling a bitterness against Anne’s having rejected him on the advice of Lady Russell and Louisa’s assertions of great generalizations about determined actions in the face of protests allured him—until he saw that in some particular cases this might end in a cracked skull.

Ellen

— Elinor Jul 17, 8:40am # - From Marilyn Marshall:

“I rented Proof after seeing Lake House to see if David Auburn had incorporated Austen into another of his works.

In Lake House, I imagine that Auburn got the writing assignment to adapt the Korean film and saw that he could work some of his ideas about Persuasion into the plot. So, whether it can be called an adaptation or free adaptation or not, as a creative artist he found an opportunity to take something dark and disturbing in someone else’s work and carry if further.

He used the Lake House plot to bring Frederick’s deepest fears of grief and abandonment to light and to show us the redemptive power of love. With Auburn’s thoughts in mind, Anne’s suffering now has a strong element of guilt and deserved punishment and the obligation to set things right. Frederick, when he finally speaks, speaks of his grief and the pain her every utterance causes him and she is the only one who can grant him the redemption he needs.

Proof, on the other hand, is an original work. After seeing the film and, coincidentally, seeing Gwyneth Paltrow playing an Emma role again, the same feelings arise that Auburn needs to tell us something about Emma and how destructive excessive devotion to a sick father can be. In the film, the father is schizophrenic—in the book, who knows what his problem is. He’s telling us that Emma had to sacrifice something precious to fulfill her father’s selfish needs. He includes the element of fear that the daughter, named Catherine, will inherit her father’s mental illness. He also includes a large puzzle to be solved (in the form of a mathematical proof)—a nod to the mystery in Emma. There is a toxic sister, who invites mockery in Mr. Collins fashion, and a warm young man who encourages and guides Catherine towards womanhood and independence. This film has the anger and frustration and a frankness about relationships that the book doesn’t.

It’s fascinating to be able to receive one writer’s critical appreciation and understanding of another writer’s work in this way. Very complimentary to Austen, but also very revealing about the imaginative processes that writers use to express their deepest thoughts about their characters’ interior lives.

There’s a powerful strain of empathy in Auburn’s two films—the audience is forced to fully experience the characters’ agony. In Austen, the mistress of subtlety, the force of empathy is like a riptide that pulls you under before you know what is happening. So Auburn combines his understanding and compassion for interior suffering with the cooler, but no less devastating, imaginings of Austen’s literary landscape, and we are the lucky recipients of this marriage of talents.”

— Elinor Jul 17, 9:09am # - From Edith Lank on You’ve Got Mail:

“The scene in that movie that resounds most of P&P to me comes when the woman who owns the little children’s book shop being put out of business by thehero’s big bad chain store visits the huge new building. She notes the cozy armchairs, children sitting on the floor reading, huge inventory of titles etc and you can just hear her thinking “to be mistress of this place would be something.” When she steps in to cover for an ill-informed clerk who can’t answer a question about the Shoes books, it’s clear she’s thinking she could make the place even better if she it were hers …

If you haven’t read I Capture the Castle all I can say is I envy you the treat still before you. And does anyone else like Precious Bane by Mary Webb? Or The Jasmine Tree?—Edith”

— Elinor Jul 18, 7:34am # - Marilyn:

“And not to forget Juliet Stevenson’s brilliant emotional performance in Truly, Madly, Deeply.

This film seems to be out of print. Netflix didn’t have it for a long time, but I notice they have it now. Deepdiscountdvd doesn’t have it and Amazon is only selling used copies. I wanted to get one for my sister—the silly girl has never seen it—so now is the time to pounce if you want a copy.

Marilyn”

— Elinor Jul 18, 7:36am # - Marilyn, you’ve sold me on it: I am a great lover of Juliet Stevenson, and with Alan Rickman. In the case of this movie, one has to ignore the absurd cover which makes it look like a silly horror film. I just got myself a used VHS ($2.08)—these are inexpensive, with the DVDs very high ($43 and up)

On You’ve Got Mail, Edith, one problem is identifying the parallels which are not archetypal, by which I mean since Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, it’s not unusual to find sparring lovers who begin in antagonism and end in love. It’s a trope, but although I dont recall the details any more, in the specific kind of wit combats the hero and heroine (Meg Ryan, Tom Hanks), the language is made to recall lines from Austen’s P&P and of course there’s the raised flag of the two discussing the book, her loving it, him beginning to read it. The idea behind “to be mistress of this place would be something” is also found in Mansfield Park: we are told either that Maria herself begins to realize “to be Mistress of Sotherton” would be something (and Sotherton is supposed to be an impressive house, something out of the ordinary as Pemberley is, though in an old-fashioned rather than modern elegant mode) or that Mrs Norris insinuates this idea and it works on Maria. So there’s an unexpected (for some) parallel between Elizabeth Bennet’s motives and Maria Bertram’: probably what we see here is Austen’s own idea of what motivated women to marry. Poor Charlotte would have leapt at such a house.

I like Precious Bane and have the recent film adaptation by Sandy Welch or maybe it’s Maggie Wadey. I don’t know if that’s the one with Janet McTeer. It’s on my TBV (to be viewed) pile. I now have a film TBV pile (at one time I had only book TBV piles). I enjoy Cold Comfort Farm (where for those who don’t know this Stella Gibbons mocks Mary Webb), but it does not deflect my enjoyment of PB. It’s interesting to know that Maggie Wadey is the woman who turned Austen’s NA into a kind of gothic film in 1986 and made the recent hostile and therefore poor (I think the recent MP is so poor because the people making it disliked the book and especially the heroine—they gave an interview where Wadey produced a curse word blanked out about Fanny and called the book boring) film adaptation. I guess she got the job through connections and having done an Austen film or this type of film; maybe the producers couldn’t believe a real_MP_ film would be generally popular and make money. Poetic justice to my mind to have had their film so damned. I’ve read I capture the Castle; the film, like the film of Cold Comfort Farm alludes to Austen, but there is no attempt to make the films adaptations of an Austen book.

Finally the Mrs Dashwood role is more capable of moving us than people realize. Now there’s a place where I think the 1995 S&S actually gives far less opportunity for a good actress to play the part properly. Jemma Jones is thrown away. Diana Fairfax (1981; she played Elizabeth in the first of the TV productions of P&P) and Janet McTeer give the role real depth, and Isabel Dean (1971; she was the mother in a not-well known production of The Weather in the Streets, and one of the central talking heads in the Alan Bennet plays; Maggie Smith played another) doesn’t do too badly either.

Cheers to all,

Ellen

— Elinor Jul 18, 7:59am # - From Laura Haywood:

“FINALLY I got to watch the Lake House tonight. So I just now read the recent spate of Lake House messages on this listI¹d been saving them for after I¹d seen the film. I admit I am surprised at how different my take was.

Here goes: I thought it was charmless and exploitive of JA. As though the producers did some focus groups and figured out that there is a Jane Austen craze going on all over world and they can cash in on it by grafting Persuasion onto yet another time travel story one that also happens to feature the box office megastars of that runaway bus movie. Wow! What a combination! Jane Austen and Speed!

I admit I never like these time travel things they can drive you crazy because they don¹t make sense and never can. But I disliked this film for lots of other reasons, too. How about the bit where he asked her why Persuasion was her favorite book and she couldn¹t say! Finally she gave up and kept repeating that it was ³terrible.² If the person who wrote that movie couldn¹t think of any way to answer that question›well, they can¹t be much of a Janeite.

I admit I felt kind of the same way about You¹ve Got Mail, although that had far more charm than Lake House. But at the time I saw it, I felt manipulated, like a bunch of producers had exactly analyzed my demographic and then created a movie tailor-made for me. They were very successful, too.

I teared up as if on cue! But that one was written by Nora Ephron who is a terrific writer and if she has my number, I guess I don¹t mind so much. I did not respond at all to this movie, however, perhaps because I¹m older now and have advanced to the next demographic group.

On the other hand, I adored Clueless and even Bridget Jones. Both movies had much to admire even if you had never read Emma or P&P. If you knew the novels, you could savor the references as they popped up, but the movies work on their own because they were so well written, witty and funny like a true JA derivative work ought to be. Lake House had no humor whatsoever that I could detect, and therefore pretty much misses the point of Austen. At first I thought the Louisa Musgrove character might provide a little humor,running around trying to get Keanu¹s attention in her silly shoes but no.

If you got this far, please forgive me›I guess I really am a cynical old bat these days. I do appreciate the recommendation and it was interesting to analyze why I felt what I felt.”

— Elinor Jul 20, 12:59am # - I much appreciate your comments, Laura. The first time I saw Clueless I disliked it very much. I thought it a cheap teenage movie which was ripping off Emma. My younger daughter, Isabel, Janeite 2 in our house, disliked it too. And she was around 20 at the time. But now I’ve come at least to appreciate it—mostly from the excellent essays it has inspired.

There are those who read Austen not as humorous, and for those Lake House is spot on—for many of the faithful and commentary type films are melodramas, Chekhovian and very little humorous.

I did enjoy Bridget Jones, the movie and also the book very much—as well as The Jane Austen Book Club, movie and book. (I recommend Sister Noon by Fowler if you agree on JA Book Club). I’ve got a book called Anatomy of Film, a much respected, central primer for film studies students and the author goes on about You’ve Got Mail in terms some people reserve for Citizen Kane. Now I liked it, and thought its use of epistolarity through email ingenious, but a masterpiece it’s not. I too cried on cue, and when I do that, I am suspicious I’ve been manipulated. Of the free film adaptations, as I’ve said before I probably like Metropolitan best, and have come to think Last Days of Disco has a central play on Emma.

I do like I have found it. It’s Indian culture and much changed from Austen as it’s a musical, but it’s powerful and interesting as a film in its own right.

I would say they should all, faithful, commentary or free, stand up as films in their own right before we praise them strongly but then we have to see they are sourced into the pool of nature as seen through Austen’s prisms.

Ellen

— Elinor Jul 20, 1:10am #

commenting closed for this article