Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

A novel many novel-readers feel called upon to read: on the latest Oxford _Pride & Prejudice_ · 23 July 08

Jennifer Ehle as Elizabeth Bennet (1995 BBC P&P)

Gentle readers,

Here we are again, with diptych reviews of what turns out to be a reissue by Oxford in 2008 of its 2004 edition of Pride and Prejudice. As I did for the 2008 reissue by Oxford of its 2004 Sense and Sensibility, I will complement Laurel’s review (Austenprose), and provide contextualization in the form of a brief survey of recent editions of the novel, film adapations available, and a discussion of how and why Pride and Prejudice has come to be such a well-known title and widely-distributed book.

So, to begin for a second time, here is Laurel’s posting on P&P:

“Any reader of the novel Pride and Prejudice, be it novice or veteran, has certain expectations and apprehensions based on its incredible popularity and renown. The same can be said for the media, whose recent over-use of its famous opening line, ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged…’ can be found repeated in the opening of many a news, magazine or blog article announcing some creditable or dubious connection to Jane Austen’s characters or plot. Interestingly, it has become the meme of the day passed along and re-used by those who want to appear in the know, but are sadly missing the point. It is debatable if Pride and Prejudice’s profound truths in can be reduced to just one-liners that are universally acknowledged. If the novel was that easy to figure out we would not care two figs about it, and after nearly two hundred years, it would have been lost to obscurity! What one can expect though is so much more; an engaging plot that keeps you thinking and re-evaluating characters every step along the way, witty, sharp and humorous dialogue that others wish to emulate but never achieve, and a love story which just might reign supreme for all eternity. With all of these expectations before us, who could not be a little intimidated? ...”

I again agree with Laurel: the latest Oxford Pride and Prejudice is not quite as good a buy as the latest Oxford Sense and Sensibility. The two have exactly the same supplemental materials: brief biographical note, bibliography, chronology, and (by Vivien Jones) appendices on rank and social status and on dancing. The difference is the introduction and explanatory notes are by Fiona Stafford. So this Oxford half-way house series (half-way between those series which have an overload and those which have too bare an apparatus) does not tailor each edition to the specific novel. The publisher may assume their readers will not buy all six books, but the reader minded to do so will buy the same supplementary materials six times1. Fiona Stafford’s explanatory notes are full and very helpful; but her introduction is disappointing because much of it (to be fair, not all), and its central perspective rehashes the many times previously-discussed theme of misleading first impressions, preconceived judgements, and slow self-recognition, for which (to take just one previous example), Tony Tanner’s essay provides a brilliant and lucid exposition2.

Elizabeth Garvie as Elizabeth Bennet (1979 BBC P&P)

To move to context, then and now: in the case of Pride and Prejudice, there cannot be any clear battles drawn over which texts to print and (if appropriate) emend. As with Sense and Sensibility we do not have in whole or part any manuscript version by Austen of Pride and Prejudice. This is lamentable since it’s thought that, like Sense and Sensibility, our present Pride and Prejudice is a much revised originally epistolary novel; it was probably the “manuscript novel, comprising 3 volumes, about the length of Miss Burney’s Evelina,” which Austen’s father sent out to a publisher in November 1797, only to see it immediately rejected. To have self-published a second book this length would have been a second costly venture, so perhaps to get Pride and Prejudice accepted by a publisher, Austen “lop’t and cropt” (Jane Austen’s letters, to Cassandra, 29 January 1813), i.e., cut and abridged her book somewhat ruthlessly. With the respectful attention Sense and Sensibility had garnered, she was then gratified to sell the copyright outright to Egerton for 110 pounds.

Thus Austen had no control over the printed texts of Pride and Prejudice at all. She was displeased by the divisions of the volumes in the first 1813 edition, blunders in paragraphing and a lack of clarity in the way the novels’ dialogues were printed, but the quick second edition (in the same year) and a third (1817) show no sign of her participation and the usual errors have begun to creep in. So there is no printed book which reflects her final decisions. The default custom is to reprint the first edition with emendation (doing basically what Chapman did), but sometimes collating the second and third. The latter option is what was done for Oxford by James Kinsley in 19703. Only with hindsight, did Austen know she could have made much more money. There is no sign she had the slightest inkling that this book above and beyond all her others would at first gradually and then suddenly by the later 20th century become a astonishingly wide best-seller.

In her review Laurel has pointed to P&P’s status. It was at first an immediately popular book among its contemporary Regency reading public. The satiric playwright, Richard Sheridan, is reputed to have said it was “one of the cleverest things he ever read” and told others to read it. Nonetheless, in the first half of the 19th century Austen’s novels were regarded as appealing to an elite taste. It was in 1870, when Austen’s nephew, James Austen-Leigh published his memoir of his aunt’s life which framed her books as sentimental romance, that the idea Austen’s books could have a general popular and wide appeal spread, and (as Henry James remarked), publishers began to work the material up.

In Jane Austen’s novels we witness a complex event of the type that the sales of the Harry Potter books represent: an initial attraction, and several intervening steps come together. After Austen-Leigh somewhat misleadingly reframed the books as nostalgic comic romances, from the late Victorian to the Edwardian era, the novels were framed as Janeism, a mixture of kitsch and arch comedy, quaint, unreal somehow, and for everyone to escape to. It is during this time we find elegant sets of books with illustrations reinforcing the comedy and sentiment of Pride and Prejudice,

1894 illustration by Thomson of Mrs Bennet and her two younger daughters

Elizabeth Bennet reads Darcy’s letter, 1870 illustration by John Gilbert

In the era leading into WW1 and since, they were reframed as comfort books—an idea brought to vivid comic life in Kipling’s famous story, Janeites. Then thanks to Chapman in the 1920s Austen becomes fit matter for scholarly editions and criticism (the equivalent of Latin classics!); by the 1930s, she is one of three acceptable women to male readers (George, Jane and narrowly Virginia).

Then came the movies. A respectable edition of Pride and Prejudice brought out just after the success of the 1940 MGM Pride and Prejudice, reproduces stills from this movie inserted as pictures facing appropriate moments in the text. Austen is attached to mythic romantic stars and a movie which was intended to offset the anxieties of a world war. In her text, Austen tells us of Miss Bingley’s sneers at the state of Elizabeth’s dress upon coming into Netherfield Park after her long walk to see Jane; Grosset and Dunlap provide an elegant and shy Greer Garson (Elizabeth) turning away from Bruce Lester (Mr Bingley):

Austen’s text tells us of a strained atmosphere during Darcy’s long and reluctant proposal; in the 1940 film, Laurence Olivier kneels passionately and beseechingly before her:

Academic careers, tourism, the heritage industry, sequel-writers (far more of them for P&P than the other 5 famous novels put together) have added their hagiographic conservative and erotic Anglophilia too.

The result: in the last quarter century, informal and formal surveys of various types have repeatedly shown that Pride and Prejudice has become one of a few transcendent best-selling woman’s novels which novel-readers feel called upon to read4.

I belong to a large software community called Library Thing, where as of the writing of this blog 459,380 people have catalogued 29,428,407 books. A software engine there informed me I am one among 20,752 people to have a copy of Pride and Prejudice. By contrast, around 10,021 members of this community own a copy of Emma; 9,456 have a copy of Sense and Sensibility; 7,143 have a copy of Persuasion; 5,883 have a Mansfield Park; 4,988 have a Northanger Abbey.

The meaningfulness of these numbers is limited since Library Thing is made up of people who own enough books to want to catalogue them, who can do the software, and who are probably more reading types than the average person. Further, one person may own more than one or many copies of a particular book. I own 11 different editions and reprints of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice in English and one French and one Italian5. Nonetheless, the sheer number of copies of Pride and Prejudice, and the discrepancy between this and the numbers of other of Austen’s novels owned at Library Thing are striking.

But why Pride and Prejudice above all? As Q.D. Leavis and others have shown, it’s not very different from Austen’s others6. Recently Laurel posted on Austenprose some revealing typical results in a survey: Pride and Prejudice is named in among the top five favorite books grouped with Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, and Jane Eyre. Such surveys have been shown to be of limited use: the answers given resemble sex surveys; people cannot be gotten to tell truth when asked what are their favorite books for real or even necessarily to tell the whole truth on whether they read the books they cite or not (we can’t check them as we can’t check what people do in bed). People are guided in how they think their choices will make them look, what kind of statement they want to make about their reading habits. The same kind of feeling guides how they respond to book covers (people don’t want to show a book cover that will make them in their own eyes look bad to someone else). And how they see or think others see the book7

But they do show us something, and that is how readers perceive the books they cite. And they perceive Pride and Prejudice as a primal archetypal and respectable romance book—to be cited in the same breath as Daphne DuMaurier’s Rebecca. In Stafford’s introduction to this new Oxford, she ignores this, the very reason for this latest re-issue of Pride and Prejudice. The reason is not far to seek; she does not want to get caught up in the real conflicts over the book; above all, the increasingly verboten to use the word feminism8. By contrast, in Vivien Jones’s introduction to the New Penguin, Jones begins with a truth not universally acknowledged that “the experienced reader of romance” as she opens Pride and Prejudice knows just what to expect: after an ordeal (in this case the heroine learns to distrust herself), she’s given her heart’s dream of a handsome man, great wealth, prestige, and tender protective love in spades.

Elizabeth Bennet (Elizabeth Garvey) has accepted the love of Darcy (David Rintoul) (1979, BBC P&P)

The question for women today is how falsifying is this vision: there seems to be but one legitimate goal for the Bennet sisters, one security (having a strong rich man), but are there no other options? There is cruelty in Austen’s depiction of a reading girl (Mary Bennet), which is reinforced by film-makers who deliberately chose flat-chested actresses and dress them up to look ugly. A rare departure is found in Fay Weldon’s depiction of Mary Bennet as lively, eager, and smarter than we realize in her 1979 mini-series Pride and Prejudice:

Mary Bennet (Tessa Peake-Jones) eager for life (1979 BBC P&P)

Yet, is it false to women’s experience of powerlessness today? and the continued prestige and power of male and male heterosexual desires in the public marketplace. In pre-feminist and now this backlashed post-feminist era, women have seen that education has not given them power, far less sexual liberation on male terms, and they turn to Austen’s version of romance as refuge, as places they can recuperate an identity they are not allowed to enjoy elsewhere. It is this perspective which leads to the aligning of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice with Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary and all her novels with modern modern chick-lit9

Which brings me once again to the film adaptations. There are 9 altogether, 5 with the title Pride and Prejudice.

Four are in historical costume. Two are of the apparently faithful species: 1) 1979, directed by Cyril Coke, written by Fay Weldon, starring Elizabeth Garvie, Irene Richards, David Rintoul, Moray Watson, Priscilla Morgan, Judy Parfitt, Tessa Peake-Jones, Barbara Shelley10; 2) 1995, produced by Sue Birtwistle, directed by Simon Langton, written by Andrew Davies, starring Jennifer Ehle, Colin Firth, Benjamin Whitrow, Suzannah Harker. Two are commentaries, where the film-makers depart in some critical way for aesthetic or thematic reasons: 1) 1940, produced by Hunt Stromberg, written by Aldous Huxley & Jane Murfin (based on a drawing room comedy by Helene Jerome), Laurence Olivier, Greer Garson, Edna May Oliver; 2) 2005, directed by Joe Wright, written by Deborah Moggach, starring Keira Knightley, Donald Sutherland, Matthew Macfayden, Brenda Blethyn, Judy Dench, Tom Hollander. Of these the 1979 is a genuinely woman-centered vision, intelligent, thoughtful, comic, touching, often lyrical:

Mrs Gardner (Barbara Shelley), Mrs Bennet (Priscilla Morgan) and Bennet girls (1979 BBC P&P)

Mrs Gardner & Elizabeth Bennet walk in Longbourne park (1979 BBC P&P)

The 1995 is spectacular, magnificent, infectious, but an Oedipal drama whose plot-design is centered on the chief male, Darcy.

Darcy’s (Colin Firth) to rescue Lydia; he stops to ask questions of and be kind to a street walker (1995 A&E/WBGH P&P)

The 1940 film maintains an importance as a social event. It was made for a mass audience, was widely-distributed and liked, and thus set a precedent of treating Austen as kitsch screwball comedy.

The 2005 is remarkable as a recent bellwether of attitudes towards Austen: she is not the dry, wry ironic writer, but someone who offers us intensities of emotion; and for the first-time we get a film which presents Mr Collins sympathetically as a misfit.

A disillusioned Mr Bennet (Donald Sutherland)

Five are free adaptations, one of which (the least known) is the fifth P&P by name: 1) 1998 You’ve Got Mail, produced, written and directed by Nora Ephron (based on Samson Raphaelson’s Shop Around the Corner, itself an update and adaptation of Nikolaus Laszlo’s Shop Around the Corner):

Kathleen (Meg Ryan) and Joe (Tom Hanks) as a sparring couple (1998 Warner You’ve Got Mail)

2) 2001 Bridget Jones’s Diary, directed by Sharon Macguire, written by Helen Fielding and Andrew Davies, starring Renee Zellweger, Hugh Grant, Colin Firth, Gemma Jones, Jim Broadbent:

Darcy (Colin Firth) and Bridget (Renee Zellweger),the happy ending (2001 Miramax Bridget Jones’s Diary)

3) 2003 P&P, produced by Daniel Shanthakumar & Kynan Griffin, directed by Alexander Vance, written by Anne Black, starring Kam Keskin, Orlando Seale, Lucila Sola, Ben Gourley, Lelly Stables, Henry Maguire, Hubbel Palmer, Kara Holden, Nicole Hamilton, Rainy Kerwin, Honor Bliss, and Carmen Rasusen (a relatively unknown updated Mormon recreation so I include the cast):

Elizabeth Bennet (Kim Heskin) bent on marriage (2003 Excel P&P)

Elizabeth Bennet (Kim Heskin) improving herself by reading The Pink Bible

4) 2004 B&P, produced & directed by Gurinder Chadha, written by Paul Mayeda Berges, starring Aishwarya Rai, Martin Henderson, Nadira Babbar, Anupam Kher, Navreen Andrews, Namrata Shirodkar, a rich mixture of song and dance that celebrates life:

Elizabeth Bennet (Aishwarya Rai) and Wm Darcy (Martin Henderson) (2004 Pathe Bride and Prejudice)

5) 2007 Becoming Jane, produced by Robert Bernstein, directed by Julian Jarrod, written by Kevin Hood and Susan Williams, starring Anne Hathaway, James McAvoy, Julie Waters, James Cromwell, Maggie Smith, Ian Richardson, Anna Maxwell Martin (the story outline and character types of this fantasy are taken from Austen’s P&P,

Elizabeth Bennet/Austen (Anne Hathaway) and Wm Darcy/Tom Lefroy (James McAvoy) (2007 Scion Becoming Jane)

As a group and individually, these movies show how film-makers have translated Austen’s Pride and Prejudice into pleasurable and entertaining visible forms which shore up a group of a “wide-spread powerful cultural myths” about family life, love, the necessity of marrying, what makes for personal happiness; they don’t take us any farther away from Austen’s books than the movies made from her other books since Pride and Prejudice comes closer to the Mills and Boon outline than any of Austen’s books.

For me they link to Austen’s novel most crucially in their repeated presentation of a woman trying to assert and hold onto her self-esteem, with respect for what she is doing and how she will be spending her life. They pass the Bechdel test with flying colors: all have at least one scene with two women talking to one another about something other than a man. This is not common among movies today.

I do not then see the key to the popular romance of the book myself just in the character of Elizabeth, let alone Darcy (whose character presentation I regard as problematic), but in Jane Bennet and her relationship to Elizabeth, in their ordeal and Jane’s continued adherence to high integrity. Jane continues not to be for sale, no matter how others see her escape from Longbourne. I am particularly taken by Samantha Harker’s performance of the role in the 1995 P&P: in scene after scene Samantha Harker is in, she provides a quiet subtle note often missing in Andrew Davies’s broad slightly caricatured canvasses:

Jane Bennet (Samantha Harker) can hardly contain her irritation (1995 A&E/WBGH P&P)

All of the P&P films have still after still of a heroine writing, thinking, reading, and landscapes to dream in.

Elizabeth Bennet (Elizabeth Garvie) writes to Jane (1979 BBC P&P)

Elizabeth Bennet/Jane Austen (Anne Hathaway) back from circulation library (2007 Scion Becoming Jane)

Elizabeth Bennet (Jennifer Ehle) and Darcy (Colin Firth) and Mr and Mrs Gardner gaze at Pemberley (1995)

Next up: the new Oxford Mansfield Park.

Ellen

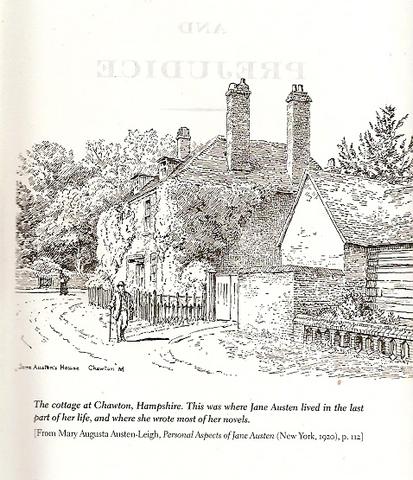

1 Supplemental materials tailored to shed light and information on the specific novel at hand is one of the great strengths of the kind of edition which provides rich supplementary materials, and of the many for P&P, I recommend no less than three: 1) the third edition (2001) of the Norton Pride and Prejudice, edited by Donald Gray, for its array of well-chosen selections from Austen’s letters, early biographical writing, Austen’s Juvenilia, and especially pieces from 20th & 21st century critical essays, which form a remarkably diverse yet coherent conversation on the novel; 2) the 2003 Longmans cultural edition of Pride and Prejudice edited by Claudia Johnson and Susan J. Wolfson, for its thick section of contemporary documents on money, the marriage market, male and female character as seen as the time, the picturesque and great houses, selections from Jane Austen’s own letters and (as there was much) contemporary reactions to this novel; and 2) the stunning achievement of David Shapard, for he has produced an easy-to-use mini-encylopedia, which (since the information is placed on alternative pages) need not overwhelm a new reader: The Annotated Pride and Prejudice (New York: Anchor, 2004). Particularly felicitious are Shapard’s choices for drawings and illustrations, e.g., the frontispiece:

Chawton

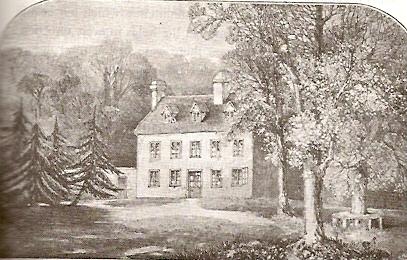

Inserted into Chapter 5, an old print of the Steventon rectory:

Steventon

and facing Volume 2, Ch 19, an appropriate image from Gilpin’s Observations (much loved by Austen):

Matlock

There are excellent fully explanatory editions of Pride and Prejudice for every level of reader.

2 Tanner’s essay was first published in book form as “Knowledge and Opinion: Pride and Prejudice,” Jane Austen (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard UP, 1986):103-141; it is also found as the introductory essay to the first English Penguin Library (1972) edition of the novel, which edition was reprinted in 1986; in the most recent or New Penguin edition of Pride and Prejudice (2003), Tony Tanner’s essay is reprinted as an appendix.

3 The 2003 New Penguin (referred to in Note 1) takes the step of adhering more closely to the 1813 text (there is no attempt to standardize or modernize the text), so as with the 2003 new Penguin Sense and Sensibility, which took the unusual step of reprinting the first 1811 text of that novel (see see “subtexts in the fight over recent editions”, the new Penguins offer readers a somewhat different text, one which may look strange, but at the same time be closer to Austen’s original manuscript and hold some new interest. The reader who buys the new Penguin can then compare it to the usual modernized 1813 texts.

4 From Anthony Trollope’s Autobiography, edd. Michael Sadleir and Frederick Page (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1980):104.

5 For Pride and Prejudice I own Jane Austen, Orgueil et prejuges, trans. V. Leconte and Ch. Pressoir, note biographique de Jacques Roubaud. Paris: Christian Bourgeois 1979, with preface by Virginia Woolf translated into Frenchy by Denise Getzler; and Orgoglio e pregiudizio, trans. Elena Grillo, introd. Pietro Meneghelli, in Jane Austen: Tutti e romanzi, ed. Ornella de Zordo (Rome: Grandi Tascabili Economici Newton 1997).

6 Q. D. Leavis, “A Critical Theory of Jane Austen’s Writings”, Scrutiny, 10 (1941-42), pp. 114-142, 272-294; 12 (1944-45), pp. 104-119.

7 It’s heartening to think women are at least not made ashamed of liking archetypal women’s books, and will cite Austen’s GWTW, Rebecca, Jane Eyre—though they can be ridiculed and shamed out of going to a womens’ film or made to think it’s bad because they don’t think about who wrote the review or that it’s the product of masculinist values. Statistically white readers outnumber those polled, so we should note most of these lists don’t reflect at all what non-white readers say they favor or read.

8 Other half-way house editions which begin at the right place frankly, the popularity of P&P and its status as an ultimate romance, include the recent 2008 reprint of the Signet edition of Pride and Prejudice with Margaret Drabble’s perceptive and candid introduction (first printed as part of this edition since 1950). Nowadays there’s an afterword by a popular romance writer (swashbucklers and bodice-rippers are part of her trade), Eloisa James whose reading of the novel makes visible just how such a lover of romance understands the book. Ms James waxes indignant over Elizabeth’s hypocrisy. It seems Austen’s heroine is a hypocrite because she doesn’t admit how much she longs to marry, see “Afterword,” pp. 377-79. My choice for my students in a general education literature course is this little Signet.

9 The feminist critique of Pride and Prejudice is well-argued by Claudia Johnson in Jane Austen: Women, Politics and the Novel (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1988):73-75, 80-84, 87-89; also Susan Fraiman, “The Humiliation of Elizabeth Bennet,” Unbecoming Women: British Women Writers and the Novel of Development (NY: Columbia UP, 1993):69-87. A really intelligent defense and explanation of women’s novels may be foun in Chick-lit: The New Women’s Ficiton, edd. Suzanne Ferriss and Mallory Young (NY: Routledge, 2006).

10 Again I list only those individuals who seem to me to have played a central role in making the film what it is.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Arthur Lindley of Austen-l:

“Today’s edition (July 24) of the Independent newspaper in the UK carries a long story about a four-part ITV miniseries called Lost in Austen, which will air in September (over here):

‘Billed as an “ingenious re-invention” of Pride and Prejudice it’s a time-slip narrative that sees Lizzie Bennet (new Bond star Gemma Arterton) swap lives with modern-day office worker, Amanda Price (Jemina Rooper).’

Don’t say you haven’t been warned. That’s www.independent.co.uk/.

Regards,

Arthur”

It never does cease, this exploitative money-making. However, it's understandable women would want to go to a movie which centers on their lives, a function which Austen's name and conservative reputation apparently authorizes. E.M.

— Elinor Jul 24, 12:59pm # - Thank you very much for this blog -lots to think about and the stills and illustrations look lovely. I’ve just got hold of a VHS video of the 1940 P&P, though I haven’t watched it as yet (it has not been issued on DVD in Britain and never seems to be shown on TV, so it was quite a find!), so am especially interested to hear your comments on this one. I’ve also got the DVDs of the 1995 P&P (I got them for Christmas but haven’t watched them yet, as I seem to be piling up films to watch!) and am looking forward to re-watching that too.

Unfortunately, as soon as I watch one adaptation, it seems to drive another one out of my mind, so I find it hard to compare them properly.

— Judy Jul 24, 2:53pm # - I have discovered at least one free adaptation of an Austen novel that does not pass the Bechdel test: in Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan: we have at least 2 women characters, they talk to one another, but not a single dialogue is about something other than a man or getting a man. The men discuss other topics, and Audrey (=Fanny Price) discusses Austen with Tom (=Edmund), but once the women are together all they discuss is men and their subtopics relate to what is thought attractive to a man (hot-waxing).

Many Austen films do pass this test—and also womens’ films. Maybe the mark of a woman’s film is that it passes this kind of criteria with flying colors.

The latest “Austen” film, a mini-series free adaptation, Lost in Austen sounds bad, but then most womens’ films described by most critics are made to sound awful.

I note that sometimes the “progenitor” of film adaptations is called Davies’ 95 P&P. Not so. It's either another P&P film, the 1940 mass audience P&P, or one of the early mini-series, and the earliest I’ve seen now are the 71 Persuasion (which has merit) and the 71 S&S (ditto). I have not seen or read the screenplay of the Austen mini-series which may be the first: it is a P&P film, made in 1967, six 30-minute episodes by the BBC, screenplay by a woman, Nemone Lethbridge.

For me undoubted masterpieces of filmic art which seriously engage with Austen’s texts are the 72 Emma, 79 P&P, 83 MP, 95 P&P, 95 S&S, 95 Persuasion (95 was a great year), the 07 NA, 07 Persuasion, and 08 S&S. All of them but 07 Persuasion are of the apparently faithful type; 07 Persuasion is a commentary. In my view, of the free adaptations the finest in the serious vein are Metropolitan, I have Found it, Ruby in Paradise and Lake House; Clueless and Bridget Jones Diary are the best in the comic.

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 26, 10:23am # - P.S.S. I see I forgot a P&P movie; it is one which combines paradigms and allusions to more than one Austen novel: 2004 Miramax Columbia Tristar Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason, produced by Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Jonathan Cavendish, directed by Beeban Kidron, written by Helen Fielding and Andrew Davies, starring Renee Zellweger, Hugh Grant, Colin Firth, with Gemma Jones, Jim Broadbent. It is, though, a Pride and Prejudice film, with borrowing from Austen's Emma, and allusions to her Persuasion.

— Elinor Jul 26, 12:35pm # - From Derrick Leigh:

“I look forward to your comments on MP and Fanny. It feels to me as though Austen was trying to produce something quite different from her previous work, although building on previous success to reach a readership. What, I wonder, was the critical reaction at the time?

Derrick”

— Elinor Jul 30, 1:38pm # - From Laura Carroll:

“”What, I wonder, was the critical reaction at the time?”

I’m looking forward to Ellen’s commentary too. The two previous instalments have been first-rate reading.

Derrick, MP was not reviewed on its first publication. It’s not clear why. Some critics think JA collected ‘Opinions’ from family and friends in part as a response to the absence of formal notices.

Laura”

— Elinor Jul 31, 11:24am # - I wrote on Janeites:

“Thank you to Laura and Derrick. As Nancy says, there was no review of MP at the time of publication; however, the story is more interesting than that. It was strongly praised in a nuanced interesting way about the characters in 1820 in Richard Whateley’s important (it’s sometimes called) review of Austen’s work in general in the Quarterly Review and you can find the excerpt in the Broadview edition of MP (ed June Sturrock). Nancy might like to know (if she doesn’t already) that Whateley singles out the character of Sir Thomas as “admirably drawn” and goes on for a full paragraph. And, as has often been pointed out since Austen herself noticed it, in the truly important review by none other than Sir Walter Scott (a big man at the time) of Austen’s novels where he praised her for having abilities he didn’t, particularly in the vein of character depth and believable, in projecting the quiet moments of life, so common acutally, and in realism, instancing Emma for these, in this important review before Austen died, the one novel he doesn’t mention is MP. Now he might not have heard of it nor been sent it.

Derrick also asks: ” It feels to me as though Austen was trying to produce something quite different from her previous work, although building on previous success to reach a readership.” It’s hard to prove but I agree with this. Her first book she published on her own, saving up for it. She had been rejected for some 25 years and had been treated with sneering insult by the man who paid her 10 pounds for NA; we don’t know if she hadn’t made other tries beyond the 1796 one by her father (probably of a much longer P&P, perhaps then a mostly epistolary novel). Then she has this success d’estime. She still doesn’t trust herself as how could she and is willing to compromise (sore as this was) and cut her “darling child” P&P and sold it off, gratified at first, but then when she saw it was actually a sort of hit among those who read and bought, it’s my belief it fired her ambition.

She was beginning to arrive, and she wrote a big book with wide application; it’s very ambitious, and it hurt her that Scott didn’t mention it. Indeed she was experiencing the fickle public who did not want her stronger morality. I feel she was still “up” from the experience, had begun Emma and again attempted something new. For all she knew the Prince’s librarian was something of a fool, she did have from him real respect as an author, and she confides in him she worried lest there was not enough doing in Emma and worried what she would do next. She was aware of her narrowness of experience and admitted to it (which is remarkable). I feel in Emma she went for stronger probability and realism than had been done before and also the use of point of view, of irony, to withhold the truth of Emma’s blunders till the end is a sharp artistic experiment which she pulled off.

But this is not what common readers want;they want excitement and look to content and sex and violence and romance: in private Edgeworth (partly jealous no doubt) called it boring, nothing happening. I feel for Austen myself and am glad she never saw that (she sent a copy to Edgeworth herself you see). Then she became mortally ill.

We can see her trying for romance and a wider world in Persuasion but she didn’t live to finish it. And not satisfied with the two halves of NA. That one was rewritten many times.

Ellen”

— Elinor Jul 31, 11:25am #

commenting closed for this article