Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

The world as "take-in:" the latest Oxford _Mansfield Park_ · 26 August 08

“I think [Lionel Trilling]’s very strange. He says that ‘nobody’ could like the heroine of Mansfield Park. I like her1” (1990 Metropolitan Audrey Rouget [Carolyn Farina] to Tom Townsend [Edward Clements])

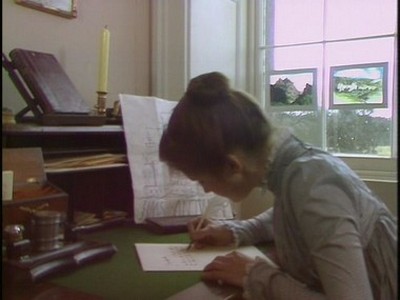

Many covers of Mansfield Park feature a grand ancient house seen in the distance (even though Austen tells us it was modern) (from 1983 MP, Fanny’s first glimpse of the house)

Gentle Friends,

As Laurel says, here we are for a third go at a series of diptych reviews. This time our topic is Mansfield Park, a book which has become controversial first as utterly dislikable—boring, distasteful, and worse yet, a grave moral comedy; and then as radical—subversive, a book intended to expose the viciousness and ruthless exploitation upon which the comfort of the powerful and rich depends, indeed the most profound and far reaching, the richest of Austen’s books, not a mere love story, which element in the book often nowadays scarcely gets a look-in by some critics.

This singling out of the book as particularly “difficult” and needing especially diligent defense begins in 1944 when the first of the 20th century texts about Austen written by non-academic ordinary women readers, popular novelists themselves, Sheila Kaye-Smith and G. B. Stern’s Speaking of Jane Austen hit the until then overwhelmingly male-dominated mostly high-minded criticism-land of Jane Austen (Mark Twain’s resentful venom and Rudyard Kipling’s ironies are rarities). You see, as Edmund Wilson then (in reaction) condescended to explain, it seems “there is something wrong with Mansfield Park and [Kaye-Smith and Stern] have a great deal to say it.” Edmund Wilson’s “Long Talk about Austen” informed the world, among others, the today still supremely prestigious Vladmir Nabokov, that Jane Austen must be included in courses of great authors; the story goes Nabokov bristled, at which Wilson huffed, so Nabokov swallowed hard and reluctantly put Mansfield Park in his syllabus2.

The iconic scene of all the MP movies: Fanny (Sylvestre Le Tousel) writing, this case her beloved brother William; in all three costumed dramas, but especially this first (1983 MP) she is the (unusal female) narrator of much of the story through subjective retrospective scenes. Here we see her in her “nest of comforts,” her attic (as yet unheated).

Another: the boy Edmund (Philip Sarson) encouraging the child Fanny (Hannah Taylor-Gordon) to write (1999 MP)

Hitherto I have confined myself to complementing Laurel’s review, with contextualization in the form of brief surveys of recent editions of the novels, covers and illustrations, film adapations available, and secondary issues about the book as a book, for “Sense and Sensibility, the problem of which text to chose (1811 or 1813); for Pride and Prejudice, some sense of a series of book and movie events which have led to the book’s having become since the second half of the 20th century a transcendent best-seller (beginning with her nephew’s 1870 memoir, and including the usefulness of the book’s archetypal strong romance for movies, careers in and outside classrooms, and the heritage industry).

I will again offer some description of other recent editions, and talk about the problem of which text to chose (we again have two texts printed in Austen’s lifetime, 1814 and 1816), and end on the movies, one of which is in my judgement a masterpiece of filmic art, the 1983 BBC Mansfield Park, one of the best film adaptations of an Austen book, and there have been many3. The difference will be this time I will discuss the book’s content directly with the aim of doing as many have done before me (I’ll quote them) explaining why there seems to be such disquiet to the point we are told (by Kingsley Amis, be it noted a misogynist in his fiction) Mansfield Park is not the real Jane Austen, is utterly uncharacteristic, a product of imposed self-denying “revulsion physical and particular.” Her heroine, Fanny Price is a type all right-minded people avoid and whose pious hypocrisy doesn’t fool them4.

So, once again, here is the opening of Laurel’s posting on MP:

“Me!” cried Fanny…”Indeed you must excuse me. I could not act any thing if you were to give me the world. No, indeed, I cannot act.” Fanny Price, Chapter 15

Fanny at the moment when Tom (Christopher Villiers) has suddenly called upon her; as she becomes the center of a scene, she is intensely distressed (Edmund, Nicholas Farrell, and Mary, Jackie Smith-Wood, sit behind her) and

Mrs Norris (Anna Massey) moves in for the attack (‘83 MP)

The rehearsal from the 2007 MP (note Fanny [Billie Piper], central & invisible)

“In a popularity poll of Jane Austen’s six major novels, Mansfield Park may come close to the bottom, but what a distinction that is in comparison to the rest of classic literature! Even though many find fault with its hero and heroine, its love story (or more accurately the lack of one), its dark subtext of abuse, neglect and oppression, and its overly moralistic tone, it is still Jane Austen; with her beautiful language, witty social observations and intriguing plot lines. Given the overruling benefits, I can still place it in my top ten all-time favorite classic books.

Considering the difficulty that some readers have understanding Mansfield Park, the added benefit of good supplemental material is an even more important consideration in purchasing the novel. Recently I evaluated several editions of the novel currently in print which you can view here. For readers seeking a medium level of supplemental material, one solid candidate is the new reissue of Oxford World’s Classics (2008) which offers a useful combination of topics to expand on the text, place it in context to when it was written, and an insightful introduction by Jane Stabler, a Senior Lecturer in English at the University of Dundee, Scotland and Lord Byron scholar.

Understanding all the important nuances and inner-meanings in Mansfield Park can be akin to ‘visiting Pemberley’, the extensive estate of the wealthy Mr. Darcy in Jane Austen’s more famous novel Pride and Prejudice. One is intrigued by its renown but hard pressed to take it all in on short acquaintance. The greatest benefit of the Oxford World’s Classics edition to the reader who seeks clarification is Jan Stabler’s thirty page introduction which is thoughtfully broken down into six sub categories by theme; The Politics of Home, Actors and Audiences, The Drama of Conscience, Stagecraft and Psychology, Possession, Restoration and Rebellion, and Disorder and Dynamism ...”.

While I’m not sure we really know how Mansfield Park rates among groups of readers, and there is evidence to suggest that like the other four novels beyond Pride and Prejudice, this one pleases slightly different subgroups of among Austen wide and varied audience5, I was relieved to find that the 2008 reissue of Mansfield Park begins with a fine essay by Jane Stabler, who while concentrating on social issues and psychology, also empathizes with its heroine’s drama of consciousness (one could equally call it); like Margaret Anne Doody in the 2008 reissue of Sense and Sensibility, she makes a strong lucid case for regarding the novel as a radical critique of Austen’s society so Stabler belongs to the second school of thought I outlined above6. Unlike the Oxford Pride and Prejudice, the 2008 MP is tailored to the specific volume. So beyond the usual appendices by Vivien Jones about rank and status in the era, and explicating dances literally and as metaphors, there is a useful brief essay on Lovers’ Vows which makes clear some of the parallels between Inchbald’s characters and Austen’s. The edition includes a bibligraphy of essays on the play, Kotzebue, and MP and Lovers Vows, and an appendix on the navy, which corrects and adds information ignored in Austen’s idealized depiction of the navy.

From the 83 MP, Fanny, Susan Price (Eyrl Maynard) and Henry Crawford (Robert Burbage):

“The day was uncommonly lovely. It was really March; but it was April in its mild air, brisk soft wind, and bright sun, occasionally clouded for a minute, and then every thing looked so beautiful under the influence of such a sky; the effects of the shadows pursuing each other, on the shops at Spithead and the island beyond, with the every-varying hues of the sea now at high water, dancing in its glee and dancing against the ramparts … ” (Austen’s MP, 3:11, Chapter 42)

The explanatory notes are very thorough, essays in themselves sometimes, and there is the usual brief biography, bibliography and note on the text.

Which gets me to the first of my additions to Laurel’s posting. As with the new Penguin edition of S&S (where Ros Ballaster reprints the 1811 text which is not bowlderized as is the 1813), in the new Penguin MP, a decision has been made to print the first text of MP issued in Austen’s lifetime—1814, printed by Egerton. Everyone agrees this one is riddled with small errors, and some suggest that Austen’s switching to Murray for the second, in 1816, suggests she was unsatisfied with it. She corrected the second as best she could: “I return also, Mansfield Park, as ready for a 2d Edit: I beleive, as I can make it” (Letters, 11 December 1815, from Henry’s London home to John Murray). Until in her original and important JA’s Textual Lives, Kathryn Sutherland argued7, that the 1811 text of Sense and Sensibility and 1814 text of Mansfield Park came closer to the spirit of Austen as they was not overly polished and corrected as she thought they had been by R. W. Chapman, people regularly used the 1816 edition as their copy text (collated with the 1814 and emended appropriately).

I have gone into the merits of Sutherland’s case before, and shown that what we have here is an agenda fight (what image of Austen does an editor want a reader to come away with) as well as a competitive business in editions. This Oxford reissue is really a reprint of the 1816 text first established by James Kinsley in 1970: he reprinted Chapman as revised by Mary Lascelles after studying the previous collations and emendations. It seems that the Penguin people are in competition with Cambridge, for the quarrel in print has been between Sutherland on behalf of the new Penguins and Janet Todd on behalf of the new Cambridge edition of Austen.

The value of the new Penguin text is that a text is provided which has not been available before (and at a much much cheaper price than the Cambridge). The interested reader could compare this 2008 reissue of the Oxford with the new Penguin. Beyond that the Penguin people decided to reprint Tony Tanner’s profound essay on Mansfield Park, one of the early persuasive explications and defense of the book along Lionel Trilling lines, with the difference that Tanner did not think we need dislike Fanny; indeed like Stabler, Tanner expects us to empathize with her. The new Penguin edition decision to print along the runners at the top of the page both the original volume and chapter number as well as the chapters when they are consecutively numbered is also very useful. Perhaps this is the most useful innovation the new Penguins offer8.

I come to the sticky part: a discussion of this troubling content. Full disclosure is best. Sense and Sensibility is my favorite Austen novel, and Mansfield Park my second favorite. The year I was fifteen I read Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for the first time, and I know it has never quite left my mind since. On any given day I can easily call it to mind, and I often do. I remember very vividly the end of my first reading experience. As I came to the closing page, and read (and my brain has this etched in) “the consciousness of being born to struggle and endure,” the thought crossed my mind, “what a strong book this is, this is the strongest book I’ve ever read,” and when I got to its last sentence, I turned back to the first page and began rereading. I didn’t want this strengthening calm to end. I also remember being astonished at the blurb which called it a “rollicking comedy.” Austen was teaching me how to survive.

Further, I have submitted a proposal to give a paper at the 2009 JASNA to be called “Disquieting Patterns in Austen’s Novels.” Among my topics will be the quasi-incestuous patterns across the six novels, and I mean particularly to deal with Fanny’s intense adoration of Edmund, partly displaced onto her brother, William. I think Mansfield Park is a novel as much about love as it is about social issues, but it’s about hidden love—so is S&S, Elinor’s for Edward, her brother’s brother-in-law, P&P, Jane’s for Bingley who has apparently discarded her and thus publicly humiliated her, Emma, Jane for Frank, Harriet for everyone, Persuasion, Anne Elliot still for Frederick Wentworth and so it goes. It is a book shaped by a mind consciously harboring a tabooed, expressly forbidden love which, if Sir Thomas were to suspect in the scene where she refuses Henry Crawford, Fanny would be horrifically castigated and outcast immediately. Much of Fanny’s behavior becomes understandable when we realize how she has to work at keeping this secret; also if we perceive the distance between her and our implicit or implied author: Austen is not influenced intensely by Edmund; Fanny is. Many of Fanny’s reactions are shaped by her intense apprehension for Edmund9.

The 1983 MP shows us Fanny emerging from girlhood listening to Edmund read aloud (beautiful and moving verse about time, place, and how through memory we invest our love from Cowper). Just look at her face:

Young Fanny (Katy Durham-Matthews) listening to Edmund, entranced (83 MP), turns into

Fanny intently absorbed by Edmund

Here we find Fanny unable to write to Edmund because she longs to disclose her love and she is alone at Mansfield, left behind (07 MP)

Audrey publicly left flat by Tom for another and beautiful girl retreats to a bathroom. It may be slightly comic to us; it is not to her (‘90 Metropolitan).

Of course whether we like a book is essentially chacun a son gout. All one can do is make visible the faultlines: what’s called the book’s moralism, and Fanny Price and the choice of life her character and fate endorses. As with Pride and Prejudice, I own 11 editions of this book, not counting translations into French and Italian10. Revealingly, one of the more popularly-oriented of my editions, one with a minimum apparatus of a perceptive and frank introductory essay by Margaret Drabble (and brief appendix) identifies most candidly and simply what makes some readers call the book moralistic: Drabble shows how over the course of the book Fanny gradually learns to accept and then to love Mansfield Park as it “offers her safety and protection;” no more than Portsmouth is this house idyllic, but rather “full of the energies of discord—sibling rivalry, greed, ambition, illicit sexual passion, and vanity” kept, just, under control; the difference are the palliations wealth provides: space, books, order, servants, beauty.

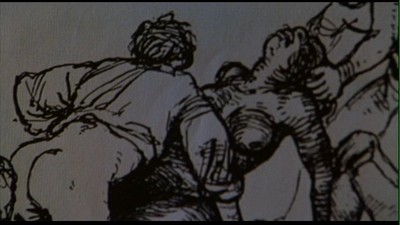

Much critical comment has attacked Rozema’s 1999 Mansfield Park, and one of the changes she makes is to sweep away this beauty and insist on the discords and the misery of those who are forced to support the house.

Fanny (Francis O’Connor) horried (99 MP)

One of the drawings she’s looking at (99 MP)

According to Drabble, Austen is exposing what goes on beneath the patriarchal surface “to demonstrate . . that life is not simple, choices are not simple, we cannot have our cake and eat it too” (xii). Mansfield Park differs from Austen’s other novels in that here she makes visible what is left latent in Pride and Prejudice—Austen was not altogether ironic when she called it “too light, bright and sparkling.” P&P was written when Austen was 20; MP was revised and completed long Austen left Steventon, had lived as marginalized gentry in Bath, had had to depend on brothers when her father died; by my chronology Lady Susan and The Watsons were drafted closest in time to this novel11.

On the other hand, and this is important Mansfield Park is beautiful, it is peaceful, it is an upper class haven of reading and peace and culture. And that too is what is today unacceptable: the aspiration to that.

The lovely exterior of Mansfield Park, the children wandering (‘83 MP)

What is usually said to be the source of the objection to Fanny was identified early on by Edmund Wilson: “The woman reader wants to identify herself with the heroine, and she rebels at the idea of being Fanny.” John Wiltshire repeats this so persuasively he’s worth quoting at length:

“In a fascinating article about the teaching of Mansfield Park in an elite college in Delhi, Ruth Vanita has shown how her students both identified with, and dis-identified with, the novel’s heroine, the quiet, submissive Fanny Price. As Vanita writes, the students recognised in the heroine’s situation many of the lineaments of their own position. As girls they are denied privileges accorded to their brothers, for instance, just as Fanny is denied the privileges given to her cousins. But the students disliked what one might call Fanny’s coping style—her quiet dutifulness, her need to make herself valued by being ‘good’. Vanita stresses how reluctant her female students were to recognise Fanny’s courage in resisting the family’s concerted attempt to make her marry Henry Crawford. Most interestingly, she suggests that the contempt some students expressed for Fanny was really self-contempt at a female role many were in reality forced to adopt in modern Indian society.

These reactions, however, are found also in Australian students, whose social situation is not at all similar to their Indian counterparts. Anglo-Saxon Australian (and ‘assimilated’) girls are generally free to choose their sexual partners or at least this is the prevailing cultural assumption—and they are not generally treated as inferior to their male peers. They, too, despise Fanny Price. Hers is a life governed by constrictions and denials, and many young readers do not want to imaginatively align themselves with such a life, or do not allow themselves to understand how little free in effect a life may be. One cannot help thinking, though, that if the truth were told, many of these students-quiet, intelligent girls, whose inner life is sustained by reading-resemble Fanny far more than they do Elizabeth Bennet12.”

For my part I think the reason Fanny is disliked is she is a creature of the book she inhabits; her character and behavior are conditioned by Austen’s larger aims which, like Trilling and Tanner, include offering a perspective which finds a life worth living in giving oneself over to quiet kindness, reciprocal consideration, a principled refusal to perform falsely, to network as we say, in order to hold fast to the self, against life’s continual chaos and cruelties. The heroine of this book is consequently someone who lives on and in herself as she is; she is in a way intensely self-possessed, not to be taken over by others if she believes they are doing wrong at the same time as she has no need to change them. She would not agree with Mary Crawford’s idea that marriage is a “take-in,” but she will not perform falsely to achieve it, and we are shown what the social world is and thus way. It’s revealing at the end of the book Mary has not married but retreated to her sister’s companionship.

I submit it is this lack of valuing socializing itself and for itself, a Rousseauian impulse that is so disliked. I find Fanny to be one of the strongest feminists in Austen’s oeuvre; what in Mary is a wary caution, but cunning which gets nowhere as Mary has not divested herself of a need for society’s false admiration, in Fanny becomes a principle. Fanny says she not see why women should be expected to jump at a man’s offer; the deeper truth is (like all the other Austen heroines) inwardly she has no need to conform or for inward acceptance by those she find deeply uncongenial. The difference is in this book to suit its theme this trait of Fanny’s is made centrally important to her personality.

Now those she finds uncongenial are the type of people who are popular by their chameleon and light way of association with others. Whit Stillman’s Audrey Rouget makes this point of view and mindset explicit when she talks of why she values conserving what is and demands a lot of herself: “Anyway it’s not a matter of losing ‘class perogative,’ whatever that means, but the prospect of wasting your whole productive life, of personal failure” (p. 182) She will not accept others’ views of Tom: “Whether I’ve been humiliated or not is something I can judge for myself …” (p. 209). She refuses to play a game called “Truth” where people are asked to candidly answer a question no matter how embarrassing; she is resented when she protests, “I don’t think we should play this,” and then when she remains unconvinced is told “Then don’t play—but don’t wreck it for everyone else” (pp. 231-32). Alas, she is drawn in to play at the end (like Fanny). The game alludes to (as it turns out as nasty as) the one Frank Churchill proposes during the picnic on Box Hill.

Audrey refuses to play: she voices a principled protest against a game that could hurt people

Which gets me for a third time to film adaptations: there are three titled Mansfield Park.

1) A masterpiece in the apparently faithful kind: in 1983 from the BBC, produced by Betty Willingale, directed by Giles Foster, written by Ken Taylor (he of Jewel in the Crown fame), starring Sylvestra Le Tousel, Nicholas Farrell, Anna Massey, Angela Pleasance, Bernard Hepton, Jackie Smith-Wood. I could go on; everyone in the cast is superb, the acting, the _mise-en-scene, the dramatic scenes nuanced and moving, the script subtle and epitomizing. I think it comes as close as one can to translating this complex novel into an equally complex film. I here can single out but one of its peculiar strengths: taking off from the book, it several times uses at length and makes central to its effects epistolarity, scenes of Fanny writing letters, with voice over by her and on occasion Edmund (Nicholas Farrell) a way of turning what we are watching into a subjective past moving into the present: we get a number of long evocative sequences of movement images which give the film depth. As for the present tense ones (of which there are also many), the Portsmouth scenes are particularly well done, no caricature, no exaggeration, none is needed13.

The pain of watching Mrs Price (Alison Fiske) defend the inferior child, the selfish sullen Betsy (who has just fought for Susan’s [Eryl Maynard] knife)

Fanny a renter and chuser of books, bringing home her treasures for

Susan (Eryl Maynard) (all from 83 MP)

2 & 3) Two commentaries: in 1999 from Miramax, directed and written by Patricia Rozema, starring Francis O’Connor, Jonny Lee Miller, Alessandro Nivola, Harold Pinter, Lindsay Duncan, Embeth Davidtz, James Purefoy; and in 2007 from Company/WBGH, directed by Iain MacDonald, written by Maggie Wadey, starring Billie Piper, Douglas Hodge, Blake Ritson, James D’Arcy, Maggie O’Neill, Jemma Redgrave. I’ve written essays on both sympathetically: on my website, “Rozema’s adaptation of Austen’s Mansfield Park and Juvenilia” and “Sex in the Austen Films” and on this blog recently, Mansfield Park Madness, where the interested reader will find links to “2007 Mansfield Park: another perspective” (Jane Austen’s World), and favorable reviews (“Mansfield Park: a natural heroine”) by two British friends of mine.

On the website if the reader scrolls all the way down, she can find yet a third review in praise of Rozema’s film, this one by Pat Cooper-Smith arguing that Rozema’s and Austen’s MPs are dark, moral works with happy endings. Less explicitly and directly so is the 2007 MP. Our first glimpse of the house in Rozema’s vision is of a haunted gothic pile; she shot the film in and around a ruin:

(Fanny’s first glimpse of house in ‘99 MP)

4) The fourth, something of a cult classic (because the writer and directer is the respected Whit Stillman14), Metropolitan (1990), is a free adaptation, also produced by Whit Stillman (it’s said he sold his New York City apartment to pay for it). The film updates Austen’s novel by dramatizing an analogous story which takes place around Christmas time using college-age upper class characters living in New York City. It’s simply so (we see) that people today do value virtue or ethical standards; the script is witty and thoughtful (it also alludes to Persuasion and Emma), and, like the 1983 MP takes place in a believable world which is in its larger reach perhaps going wrong (in the workplace, at home) but where there is much to compensate in pleasure and personal development and even idealism.

Audrey (the Fanny character) is a shy bookish girl who is self-contained in the way of Fanny Price, thoughtful, kind, but no angel. One of the most touching scenes of the film occurs Christmas eve: Tom (the Edmund character) stays at home watching Channel 11’s firelit log with his mother (she is divorced and without him would be all alone); during the day Audrey is still buying presents, and in the evening with her mother goes to St Patrick’s Cathedral for a ceremony whose music and hopefulness move her to tears.

Audrey crying at St Patrick’s (1990 Metropolitan)

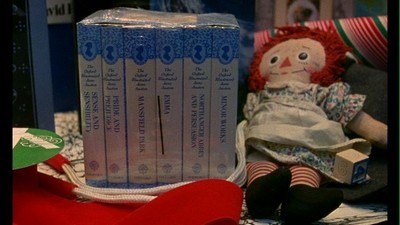

The set of Austen glimpsed by Fanny in a Doubleday window that day

See this movie and you will genuinely get a sense of how Austen’s characters and values might appear in life today. The one draw-back is it does not pass the Bechdel test. We have more than two female characters; they talk to one another, but all the dialogues, every one concern either one of the male characters or getting a man. You must read Austen’s book to find yourself among women discussing things other than love and need for a man and questioning this as a necessity.

Next up: Emma.

For the two previous reviews, see “Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice. For more just on the issue of the texts, Austen Unchapmaned and Austen: subtexts in the fight over new recent editions.

Ellen

Notes

1 Metropolitan, in Whit Stillman’s Barcelona/Metropolitan (London & Boston: Faber, 1994):192-93.

2 See (and read if you haven’t as yet) the fascinating Sheila Kaye-Smith and G.B. Stern’s Speaking of Jane Austen (New York: Harper, 1994), published n England as Talking of Jane Austen; Edmund Wilson, “A Long Talk About Jane Austen,” Classics and Commercials: a literary chronicle of the forties (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Cudahy, 1951):196-203; and the overpraised “Jane Austen: Mansfield Park,” in Vladmir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature, ed. Fredson Bowers (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980):9-60. Nabokov analyzes the design and themes of the incidents at Sotherton and the play-acting, but the description of Austen’s novles as “delicate patterns, with her collection of eggshells in cotton wool,” in comparison say to the rich wide world (“tawny port”) of Dickens reveals the masculinist disdain of Austen: he writes: “Personally I dislike porcelian and the minor arts … Let us not forget there are people who have devoted to Jane all their lives, their ivy-clad lives …” and so on and so forth (p. 63).

3 For me undoubted masterpieces of filmic art which seriously engage with Austen’s texts are as follows. The apparently faithful adaptations: 1972 BBC Emma, 1979 BBC P&P, the 1983 BBC MP, the 1995 BBC/WBGH P&P, 1995 Miramax S&S and 1995 BBC Persuasion (95 was a great year). The commentaries: 2007 Persuasion and 2008 S&S. The free adaptations: Whit Stillmans’ independent 1990 Metropolitan, the Tamil 2000 I have Found it (S&S), Victor Nunez’s independent 1993 Ruby in Paradise (NA) and the 2006 Warner Lake House (Persuasion) seem the best in the serious vein, the Amy Heckerling’s 1996 Paramount Clueless (Emma and 2001 Columbia Tristar Bridget Jones Diary (P&P) in the comic. I also find of real interets the 1987 BBC NA, 2007 BBC/WBGH NA , and the much-maligned 2007 ITV MP

4 Kingsley Amis, “What Became of Jane Austen,” Jane Austen: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Ian Watt (NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963):141-43; Marvin Mudrick, Jane Austen: irony as defense and discovery (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952); 155-80.

5 As I wrote in my Pride and Prejudice survey, a concrete survey of actually-owned books at Library Thing showed MP to come second to last; it’s NA which is the least owned of Austen’s books; NA is also the most infrequently filmed (only 3 movies available). In the area of sequels it does as well as Emma; readers want to rewrite the ending of MP and they will to “fill” in Emma; see Jennifer Scott, After Jane: A Review of the Continuations and Completions of Jane Austen’s Novels (Privately printed, 1998); it often forms in combination with others, as in Diana Birchalls’ Mrs Darcy’s Dilemma which combines central plot-design and incidents from MP with the hero and heroine (reconfigured) of P&P; see Deirdre Shauna Lynch, “Sequels” in Jane Austen in Context, ed. Janet Todd (Cambridge, 2005):160-69. To conclude, MP sells; not as extravagantly as P&P but it doesn’t do badly :). We really have no way of telling what is the norm. We only know what gets into print, what people are willing to say aloud or write; they are not on oath (it’s like a sex survey) nor does everyone write. I think the book is such that people are nervous to say what they feel. They are embarrassed to admit to identification with the heroine, or to admit openly why they dislike her so when it’s fervent resentment.

6 In general the editors of the heavy apparatus books perforce find themselves taking the view that through this intensive picture of private life we get an extensively suggestive picture of early 19th century England, politically, socially from a post-colonialist, feminist, and slavery standpoint. A really fine introduction, one which makes the same case as Stabler is June Sturrock’s Mansfield Park Broadview edition: she provides contemporary documents (about the play Lovers’ Vows, religion at the time [which Stabler skirts somewhat], education, women, slavery and West India, improvement, poetry, which support both Sturrock and Stabler’s essays. The Norton Critical edition of Mansfield Park by Claudia Johnson includes the whole of Inchbald’s free translation/adaptation, yet richer contemporary documents (parliament debates excerpted, Clarkson’s History of slavery, Inchbald’s comments on Henry VIII, read by Henry Crawford and of real interest in seeing how it relates from a woman’s point of view to Austen’s novel) and some excellent essays, but this appears to be one of those paradoxical editions of MP where the editor while analyzing the book with great interest (and in Johnson’s case arguing for subversion) nonetheless seems to dislike the book. Johnson has four essays where it is asserted we must or do dislike Fanny and make the book an arduous effort and irritating (Nina Auerbach makes our dislike of Fanny the very center of her discourse) and are themselves written in an abstract style or show the writer defending a thesis which is not quite tenable (about dating for example—a vexed topic in Ausen’s studies). The cover illustration is the Rice portrait which in an earlier publication Johnson argued fiercely was of Jane Austen; she backs off here but nontheless prints the image which is coyly provocative, clearly in costume and facial features not Jane Austen. So the reader stands warned.

7 Once again in the case of Mansfield Park, we have no manuscript. The value of Sutherland’s work is to have studied the manuscripts we do have and shown how flexible and subtle is Austen’s punctuation and grammar, how she wrote at a rapid pace of invention and rewrote and polished and revised her texts over the years. See Jane Austen’s Textual Lives: from Aeschylus to Bollywood_ (Oxford, 2005), particularly 291-313.

8 Beyond Sutherland’s introductory essay (which takes the same sort of stance as Stabler, only it’s shorter and more abstract and harder to understand), Sutherland provides a useful textual history of MP for the 19th century, a thorough defense of her decision to reprint the 1814 text, Tanner, and rather shorter notes than Stabler. See Kathryn Sutherland, ed. Mansfield Park (NY: Penguin 2003).

9 The angle I will study the novel from has been noticed numerous times before, e.g., most recently Glenda Hudson, Sibling Love and Incest in Jane Austen’s Fiction (London: Macmillan, 1999); Maaja Stewart, Domestic Realities and Imperial Fictions (Athens: University of Georgia, 1993); Richard Handler and Daniel Segal, Jane Austen and the Fiction of Culture (Tucson: Arizona University Press, 1990); Susan Morgan, Sisters in Time: Imagining Gender in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction (Oxford UP, 1989) Articles include Paula Marantz Cohen,”Stabilizing the Family System at Mansfield Park,” English Literary History,” 54 (1987); (notoriously), “Sister-Sister,” by Terry Castle, a review of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye, London Review of Books, 17 (3 August 1995):3-6; J. David Grey, ”’Our Little Brother’”, Persuasions, 3 198); “My Only Sister Now:” Incest in Mansfield Park, Studies in the Novel, 19 (1987); Susan Lanser, “No Connection Subsequent: Jane Austen’s World of Sisterhood,” The Sister-Bond: A Feminist View of a Timeless Connection (London: Athene, 1985).

10 For Mansfield Park I own Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, trans. Denise Getzler, Paris: Christian Bourgeois 1982; and Mansfield Park, trans. Maria Felicita Melchiorri, introd. Pietro Meneghelli, in Jane Austen: Tutti e romanzi, ed. Ornella de Zordo (Rome: Grandi Tascabili Economici Newton 1997).

11 Margaret Drabble’s is a superb essay on MP and makes the Signet edition (1964; reprinted 1996) one of the best buys on the market; I recommend another of the brief apparatus type: Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, as introduced by Amanda Clayburgh for Barnes and Noble (New York: 2004), with a proviso or qualification. Clayburgh takes a somewhat unusual direction for today: she concentrates on the use of countryside and improvements and how this is linked to theatricality and the play-acting in the novel. This was common in the 1970s (Alistair Duckworth’s The Improvement of the Estate is the prime example), but Clayburgh gives these topics a new turn, bringing in for example the story morality of the book (thus her comment about Edmund’s profession, the house chapel they visit at Sotherton and how these play out against playacting). Alas, she opens and closes with adament insistence on how “we all dislike Fanny Price.” She can only speak for herself.

12 See John Wiltshire, Jane Austen: Introductions and Interventions (London: Palgrave, 2003):116-17. He is also the editor of the Cambridge edition of _Mansfield Park and in this book mounts a sensible defense of reprinting the second revised text, 57-69. He does not however bring up how the sentence omitted from the 1813 edition was put back by Chapman and nowadays left out. For a moving essay sympathizing with and admiring Fanny, see Emiliy Auerbach’s Searching for Jane Austen (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004):166-200.

13 There is an essay which does justice to this film, unfortunately, it uses the occasion to attack Rozema’s: see Jan Fergus, “Two Mansfield Parks: purist and postmodern,” Jane Austen on Screen, edd. Gina and Andrew F. Macdonald (Cambridge UP, 2003):69-89.

14 See Mark C. Henrie, Doomed Bourgeois in Love: Essays on the Films of Whit Stillman (Wilmington, Delaware: ISI, 2002). This book has a number of essays linking Stillman’s films individually and as a group to Austen’s books.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Super job Mrs M, super job…. Tom

— T. Wood Aug 26, 7:28pm # - Hi Ellen, such a wonderful tribute to the many different interpretations of Mansfield Park, good and bad. I think of all of Jane Austen’s major novels, MP has inspired readers/filmakers into the most interesting opinions on the novel and its characters. I adore Fanny Price, and will admit it publicly!

I will be an air-head in the minefield of scholarship and proclaim Miss Price’s periwinkle gown in the “I could not act any thing if you were to give me the world” scene in MP 1983 a triumph, and give all the credit to BAFTA award winning costume designer Ian Adley. Honorable mention in the “kinda odd department” goes to Mary Crawford’s orange and black frock that makes her look rather more an advertisement for Halloween than a genteel Regency lady out for a walk to MP! Can one assume that the color combination was haute couture in London at the time? I know, I am transposing my 21st-century sensibilities on 19th-century styles, but I could not let it go without throwing it out to you, a woman of refinement and good taste, to be sure!

Thanks again, Laurel Ann

— Laurel Ann Aug 26, 8:57pm # - Dear Laurel,

The blog through irony mocks and then critiques those who condemn MP and Fanny Price.

The costumes and hairstyles combine mild historical accuracy with acceptable “lady’s” fashions (as dreamt up by women today when they go to expensive shops) in 1983. All the films do this: they combine some historical accuracy with what they think the viewer at the present time would like to see. Hairstyles are especially anachronistic. Attention is paid to what will make the particular actress look appealing to the present-day audience.

The exceptions are characters we are to dislike. The costumers given full reign to dress them in contemprorary dress which is often somewhat alienating. In the case of women before 1995 and again recently women characters we are to dislike or think of as not chaste are made to wear very low cut gowns and those awful push-up bras. I feel sorry for the actresses in such contraptions; they look uncomfortable and (to my eyes) absurd. Like peacocks (just like men who are we are to dislike are presented as fops; I find an anti-homosexual message in this latter stigmatizing).

Ellen

— Elinor Aug 27, 7:09am # - From John O’Neill:

“Ellen,

I enjoyed and appreciated this chapter of your blog. I especially liked the paragraph on how Austen’s novels are about hidden and illicit love, and how Mansfield Park makes that element stronger than most of the others. I intend to use the ideas in that paragraph in my teaching of the novel this fall.

I look forward to reading your JASNA paper in some form eventually.

John”

— Elinor Aug 27, 9:24am # - I enjoyed reading this blog and Laurel Ann’s, and have been thinking about Mansfield Park all day… trying to come up with some thoughts on why it is that so many people seem to have difficulty in liking Fanny Price, as with other quiet, “good” and yet determined heroines like Richardson’s Clarissa and Dickens’ Esther Summerson.

Maybe it’s because Fanny is reserved, and her rebellion against the society around her is kept inward, to a large extent – but also perhaps because she refuses to be a romantic heroine, instead trusting her own judgement and refusing Henry.

After reading your previous blog, I’ve just re-watched the 2007 film, which I like within its limits, as I said before, even though so much is lost. It struck me again that, when you look at the story so pared down, it does seem as if in traditional romance terms Henry ought to be the hero – the dashing, witty outsider trying to sweep the quiet country girl off her feet. So maybe some readers and viewers get angry with Fanny when she refuses to act the part of heroine, just as she refuses to take part in the amateur theatricals. A lot of readers of Clarissa seem to fall for Lovelace, despite all the terrible things he does, just because his language is made so seductive – and maybe some of them fall for Henry Crawford too? (I’m aware there is also similar criticism of Trollope’s Lily Dale for refusing to marry Johnny Eames, though of course he is nothing like Lovelace – but again, the heroine (and of course the author) is denying readers a romantic consummation.)

On the 2007 film, I can’t think of much to add to my previous comments. I do find it sweet/touching and am now less worried than I was on first viewing by Fanny’s constant running about and the shaky camerawork.

I don’t think I said anything about the portrayal of Tom, played by James Darcy, but, re-watching, he struck me as an interesting figure in this adaptation – the way he is dissatisfied with the country life which suits Edmund, and wants to break out of it, as his sisters do. But Tom can be redeemed after his “fall”, whereas there’s no way back for Maria.

— Judy Aug 27, 4:20pm # - Laurel writes:

“Ellen, such a great blog! I think that it is our finest effort yet (most definitely more you). Your images and the concepts you pulled together were brilliant and I have had positive feedback.

Did you know that you are referenced as a source on Wikipedia for your essay regarding Southam & MP? Quite a complement.

Quick question for you. I am attempting to find the original publishing source to cite the comments that Jane Austen collected from her family and friends for MP after its publication. Henry Churchill has them on his Jane Austen Info Page, but I can not find where he got the info from. Do you know? I think that it might be from the book Jane Austen a Family Record, by Wm. Austen-Leigh & Richard Arthur Austen-Leigb, but can’t find the list.

Can you point me in the right direction?

Thanks again, LA”

— Elinor Aug 31, 6:53am # - Dear Laurel,

Thank you for the compliment and I do think what we are doing when all done will be a contribution to Jane Austen studies on the Net—even if we are not recognized by people with Big names or belonging to Important institutions. Wikipedia is a an enormously useful compendium of information used by uncountable people.

Good quick question. At first it stumped me and I went over to the Broadview and Norton editions but saw quickly that not enough information was given beyond the title “Opinions of Mansfield Park … ” However, armed with that I did think of where to go: David Gilson’s Bibliography of Jane Austen. The next time you want to splurge on a central tool for finding out everything feasible published on JA until 1997 (when it was last published) buy this book. His index took me to “A6, vii," where I read these opinions she collected from family and friends exist as a manuscript in her handwriting now in the British Library (Add.MS. 41253A).< br />

Extracts were first published by James-Edward Austen-Leigh in the 1870 Memoir, and then (as you guessed) Wm Austen-Leigh and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh’s Life. In 1926 they were reprinted together with comments she collected on Emma and “Plan of a Novel” under the title Plan of a novel according to hints from various quarters by Jane Austen, with opinions on Mansfield Park and Emma collected and transcribed by her, and other documents. This appears to be a publication by R.W. Chapman, as Chapman printed the whole in Minor Works.

Where can you find a complete text of these? If you have Chapman’s _Minor Works, they are there; they are reprinted by Claudia Johnson in the Norton MP. LeFaye reprints a selection of them as part of a paragraph in her Family Record; I’d be careful with LeFaye; she is a handy source, but constraints of space force or allow her to paraphrase, and when she paraphrases she has an agenda and she is unscrupulous sometimes in giving a slant which can misrepresent a text—or maybe she just misreads it.

I hope this helps.

Ellen

— Elinor Aug 31, 6:55am #

commenting closed for this article