Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

"a heroine whom no one but myself will much like:" the latest Oxford edition of _Emma_ · 22 September 08

Emma. The book of books. A remarkable novel where when a story or character suggestively goes through Emma’s mind since she half-gets it wrong, and sees it partially, we are invited to imagine it whole—so one novel becomes many in potentia.

Mr Knightley (John Carson) has just told Emma (Doran Goodwin) he cannot love Jane Fairfax because he can love an open nature only; she has reciprocated by telling a joke against herself, and he laughs not in triumph or meanly, but out of a spirit of deeply congenial camaraderie (‘72 Emma, screenplay Denis Constanduros)

Dear Friends,

As Laurel says, here we are for the fourth in our series of six diptych reviews of the latest Oxford reprint of Jane Austen’s novels contextualized against a background of controversies, scholarship, book illustrations and film adaptations. This time I will also provide a counterpart to Laurel’s review by, like her, talking about what makes Emma an important and perplexing book1.

So, here for a fourth time is Laurel’s opening:

“Be satisfied,” said he, “I will not raise any outcry. I will keep my ill-humour to myself. I have a very sincere interest in Emma . . . There is an anxiety, a curiosity in what one feels for Emma. I wonder what will become of her!” (Mr. Knightley, Emma: I:5)

Mr Knightley (Jeremy Northam) worrying about Emma’s new friendship with Harriet while Mrs Weston (Gretta Scacchi) remains confident, for she empathizes with Emma’s motives (‘96 Emma, screenplay Douglas McGrath)

For me, reading Jane Austen’s novel Emma is a delight. However, not all readers have been in agreement with me over the years including Jane Austen herself who warned her family before publication “I am going to take a heroine whom no-one but myself will much like.” She was of course making fun of herself in her own satirical way; her critics, on the other hand, were quite serious. When the book was published in 1815, Austen sent a copy to her contemporary, author Maria Edgeworth who gave up reading the novel after the first volume, passing it on to friend and complaining, “There is no story in it.” Others had mixed feelings offering both praise and blame for its focus on the ordinary details of a few families in a country village. One important advocate of Emma was Sir Walter Scott, whose 1815 essay published in the Quarterly Review represents the most important criticism on Austen’s writing during her lifetime. To be recognized by his pen put Jane Austen in a whole other league of writers. She must have been quite giddy when he heralded her Emma as a ‘new style of novel’ designed to ‘suit modern times’ ....

*************

Like all the other latest Oxfords, the text here is a reprint of the 1971 text edited by James Kinsley (basically an emended reprint of Chapman’s 1923 text as revised by Mary Lascelles). As with Pride and Prejudice, there is no alternative first text as there is no manuscript and Austen died before a second edition could even be thought of. Like latest reprints of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, we also get exactly the same supplemental materials: brief biographical note, bibliography, chronology, and (by Vivien Jones) appendices on rank and social status and on dancing. The notes are a reprint of the 2003 notes Adele Pinch wrote.

As Laurel says, Adela Pinch’s introduction to the latest 2008 Oxford reprint2 of Emma emphasizes how different Emma seemed to most novels to readers of the era; Pinch tells us how bored Edgeworth said she felt in a letter to a friend. Since it was Austen who sent a copy of her book to Edgeworth (probably out of pride in an achievement), I, for one, prefer to assume this comment never got round to Austen. Not that Austen is herself shy of criticizing other novelists harshly or (at least in her letters to her sister) at all unsure of the high and exquisite quality of her artistry. Her response to Scott’s review was to complain he left out Mansfield Park.

Pinch goes on to say that Scott’s remarkable review focuses precisely on what he felt made Emma so noteworthy he had to record it himself: its use of quiet diurnal events so understated and unextraordinary that we can be fooled into thinking the book is as real as the lives going on around us. Pinch considers this kind of texture “revolutionary” and discusses how Emma’s blunders amid such everyday experience as shopping and gossip, makes readers question how they know what they know2. Fiona Stafford’s introduction to the (2003) New Penguin3, takes the same stance and uses the same text: there too we begin with Scott’s review; the difference is Stafford then goes on to suggest this realism is an illusion Austen set up and continually undercuts by her use of puns, allusions, games, coded names and parody

It is common for people writing on Emma to begin with taking it as an extraordinary achievement as well as a book somehow more fully representative of Austen’s art than any of her others4. And it is now de rigueur (as Pinch and Stafford do) to single out free indirect discourse as Austen’s invention too, when in fact it may be found (though crudely done) in many earlier novels. Nonetheless, it is not true that free indirect discourse and quiet diurnal probable realism were new or unique to Emma: precisely this mood and versions of this kind of discourse can be found in novels by Charlotte Lennox, Sarah Fielding, Mary Brunton (Austen complained about one of her books perhaps because in another so like Emma that were it not for its date, it’d be called a source, Discipline), and among the French writers who Austen read, Isabelle de Charriere, Stephanie-Felicite de Genlis, Adelaide de Souza and Isabelle de Montolieu use free indirect discouse & quiet diurnal realism5. Further, what Scott is actually astonished by is Austen’s ability to conjure up in an excited, spirited and original way a complexly believable ordinary character, not a fanatic, not grotesque, not in psychological extremis; that is what is beyond him he feels6.

The important innovation of Emma forms the centerpiece of a central critical text of our time: Wayne Booth’s Rhetoric of Fiction where he is deeply troubled by a technique or element that he feels distinguishes modern or 20th century novels from just about all earlier ones: an unreliable narrator whose morality is appallingly bad or pernicious.

In Emma Austen did something so innovative and controlled that it was not imitated with a similar artistic consistency until Gustave Flaubert’s Emma Bovary. (It’s no coincidence Flaubert called his erring heroine, Emma.). At the center of Austen’s novel is an unreliable narrator toward whom her implied author takes an ironic or distanced stance. This in order to present us with a self-centered self-regarding, blundering as well as startlingly blind, domineering, very rich and snobbish, and at times malicious heroine:

Emma (Kate Beckinsale) judging Harriet’s (Samantha Morton) love coldly; in this film Mr Martin (Alistair Petrie) does remember to bring The Romance of the Forest; and then Emma reinforces her scorn for Harriet’s choice:

(‘96 Emma, screenplay Andrew Davies):

(‘96 Emma, screenplay Andrew Davies):

Why did I call this perplexing? Well Austen as implied author gives Emma qualities she likes, nay identifies with: as a composite whole, Austen wants us to recognize Emma as part of ourselves. Sometimes Emma is all kindness, especially towards her father:

Emma tells her father, Mr Woodhouse (Donald Eccles) she means to marry Mr Knightley & he refuses to accept it (‘72 Emma)

As numerous critics have written, it is difficult to know how we are to judge any particular character, incident or utterance when the innovation (ploy, trick) is to make the heroine, its “central reflector” (to use Henry James’s term) our unreliable and only narrator except for

two chapters where the free indirect discourse is used to make Mr Knightley our reflector (I:5 & 3:5);

occasional carefully unobtrusive narratives and interjections by our implied author when it is necessary for us to know some piece of history or point of view we would be in danger of misunderstanding were we to be given it by Emma (e.g, most of 1:2, 2:2, the first sentence of 2:4),

and obstreperous or apparently obtuse characters who will act or have their say irrespective of Emma’s wishes (e.g., Mr Weston and Mrs Elton in the 2nd through 28th paragraph of 3:6 or this scene:

At Emma’s dinner party, Mr and Mrs Elton (Timothy Peters and Fiona Walker) indulge in a cruel insult of Jane Fairfax (Ania Martin) when they laugh at the notion she may be writing letters to a lover; as with Harriet, Mr Knightley (John Carson) earlier rescues Jane from mortification by coming over to converse quietly with her (‘72 Emma).

Now Booth sees the development after Austen as dangerous since the reader is seduced into identifying and sympathizing with such central consciousnesses and amorality is reinforced and made acceptable. He suggests there had been unreliable narrators before, but the first one, Austen’s, is in a book that carefully discriminates between what is right and wrong by having an alert and active enough implicit author and a heroine who is basically a good person even if flawed, one whose happy ending we are to rejoice in7. Myself I can think of dozens of novels where just this combination of dramatic irony, mystery and alternating sympathy and alienation is the reigning technique, and most of them those by women have narrators we are ambivalent about8.

Where the problem with Booth’s analysis comes up is how sure he is that all readers admire and rejoice in Emma herself. He seems at times to forget Austen’s famous statement upon embarking on writing the book: ‘I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like9’. While on the Internet among common readers of Austen, Fanny and not Emma wars have become famous, it doesn’t take long before coming across strong dissenters from Booth’s complacent delight in Emma, for his is a father’s view of his wonderfully loving, smart and finally submissive daughter (rather like Mr Knightley who he also admires very much), and thus very different interpretations of the novel.

Of those who cannot like Emma and rigorously find faults and flaws in the book or are candid in asking how we are to take a scene that seems to ask us to accept an obnoxious or now obsolete social attitude, I name Mark Schorer, Margaret Drabble, Arnold Kettle, and most recently Avrom Fleishman10. Fleishman’s essay is the most intriguing since like Austen he uses an ironic tone: he presents this strange young woman without telling us what her name is (except since it’s in Todd’s book under Emma we must guess). Austen’s heroine emerges as a sexually frustrated neurotic woman tied down to a imbecilic weak (unconscious) tyrant. This over-the-top yet persuasive (you have to read the essay) interpretation stays with one because of the use of irony, and I at least was left wondering if this psychoanalysis is more accurate than we like to admit.

Fleishman’s view coheres with the more traditional approach of Schorer who sees the sexual frustration and fear in Emma and who also resembles Booth because in the end he feels Emma is rightly rewarded with Mr Knightley and qualifiedly adult contentment after she has been humiliated. Schorer’s is a punitive masculinist interpretation. For my part I find Margaret Drabble’s frank disssent and discomfort with Emma and her puzzles over where Austen is in this book and what she expects us to think and feel among all this irony the most illuminating essay in conventional print about it. Far superior to Pinch or Stafford.

This latest Oxford Emma does differ in one way from the three latest Oxfords Laurel and I have reviewed: like the others, we get a detail of a picture of an attractive young woman so angled that the picture becomes a close up; however, this time the choice (as in 2003) is George Dawe’s Portrait of Mrs White (nee Watford), Full Length in a White Silk Dress (1809) and angling the camera this way makes the woman’s breasts prominent and (as it were) in the viewer’s face. So the volume participates in the recent fashion for exposure of breasts on classic or high status novels (and their sequels), a pornification which matches this decades fashion, even if the use of old images precludes also presenting an anorexic sexy model.

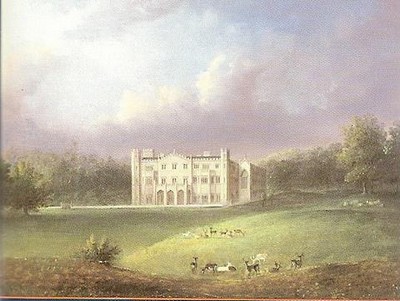

More appropriate to Austen’s subdued book are the images of ordinary social life which provide the covers for the books which provide full apparatuses, e.g., the two Norton editions thus far (of an1817-18 assembly at Clifton) or the choice for the Longman Emma (ed. Frances Ferguson) of a contemporary image of Apley Priory, an 1811 mansion which included medievalizing elements that made it resemble an abbey:

Countering the insistence on the lifelike believable characters and place, is an equally strong tradition where it’s demonstrated how idyllic, leisured, insular, narrow and protected is the world our heroine is conscious of and lives wholly in11. The 96 McGrath Emma creates a remarkably pretty version of an English village, rather like a dainty holiday postcard:

Emma draws Harriet (Toni Collette) while Mr Elton (Ewan McGregor) looks on

Emma and Harriet stroll through a wood

More appropriate than a huge elegant romanticized mansion or exquisiteness picturesqueness would be a picture of a quiet country village, something anticipating Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford. And the first of the above three stills does have something of this.

*************

To return to the differing ways Austen’s unreliable narrator leads to us reading Emma, all these at variance views account for an interesting reality of the film adaptations of Emma. While the apparently faithful film adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility are closely alike in many ways, and even the free adaptation and commentary type movie of Mansfield Park (by which I mean the 1990 Metropolitan by Whit Stillman, and the 1999 Rozema MP and 2007 Maggie Wadey MP) resemble the apparently faithful 1983 BBC MP, the Emma adaptations are all over the place. For example, nothing could be more unlike Davies’ film than the equally apparently faithful Miramax Emma (written and directed by Douglas McGrath) made in the same year.

A downright hostile reaction to Emma might account for much that might surprize a reader of Emma in the 1996 Meridian A&E/ITV Emma written by Andrew Davies (produced by Sue Birtwistle, directed by Diarmiud Lawrence). Not only does Davies make Mr Martin (Alistair Petrie) and Mr Knightley far more central to the story’s development compared to Emma (Kate Beckinsale), Harriet (Samantha Morton), and Jane Fairfax (Olivia Williams), Mark Strong is presented as (how shall I put it) capable of becoming abusive. He is never soft or tender with Emma until the end, and then he is condescending. He snarls. He is endlessly ferocious, on the edge of an explosion, and then moves into unexplained furies. In Davies’ Emma, when Emma insults Miss Bates (Prunella Scales), Mark Strong actually pushes Kate Beckinsale roughly, he bends her elbow and shoves her into the carriage. (It’s not a coincidence that Strong played the torturer in Syriana and also plays hard macho men in other films.)

A rare less fierce moment occurs when Mr Knightley asks Emma to marry him; here he is startled to find she does love him and is about to say yes (‘96 Davies Emma)

Sarah Caldwell’s book on Davies quotes Davies as saying there’s something “odd” or funny going on with Knightley in Austen’s book and I think that careful attention to this film adaptation (instead of just sitting there cataloguing what is faithful literally and what not) would show this film is about the unconventional sexualities Davies thinks are in Emma, including Frank as capable of sadism and altogether too interested in Jane’s skin. I agree with Davies about Austen’s Frank but think Davies has overreacted to Austen’s provocative (to men more than women perhaps) heroine.

By contrast, the McGrath Emma is a moving fairy tale, an attempt at presenting a feminine point of view by a man, a movie which exonerates Emma herself as an innocent well-meaning child. Many of the stills fixed to resemble antique pictures from some romance you once read a long while ago. Everything about it in the framing announces happiness, complacency, oh how lovely is the universe, it’s woman’s film as delicate. As with the 1995 S&S, it has soft voices and lovely background music, outdoors scene set up to be artificially picturesque. The picnic photographed as a fete champetre.

Jeremy Northam’s Mr Knightley is all vulnerable hurt and tenderness:

Mr Knightley (Jeremy Northam) hesitantly, sweetly attempting to speak to Emma (Gwyneth Paltrow) who stops him (‘96 McGrath Emma).

I’m not alone in thinking the oldest of the group, the 1972 Emma remains the masterpiece of serious engagement with the themes and characters of Emma; it’s not even an unusual view, and recent handbooks meant to help teachers decide which film adaptations of Emma to use still include it in their purview12. Conceived as a drawing-room comedy, with only the iconic Box Hill scene done on location, nonetheless, the 1972 Emma presents a complex ironic portrait of Emma; it is rare film to achieve an ironic stance towards the heroine. Glenister is on record as having read Mark Schorer’s essay; he says he chose Doran Goodwin because her large labile face can convey a variety of complex moods, but most strongly someone on the edge (rather like Anna Massey).

The supporting cast is excellent. Ania Martin is a Jane Eyre traumatized Jane Fairfax, whose songs project her isolation, longing and a deceitful relationship with Frank (Robert East): one Scots song suggests they are alienated from those they find themselves hopelessly dependent on; I’ve never seen anyone come near Fiona Walker as the highly sexualized, domineering Mrs Elton (she flirts with Mr Knightley) whose obnoxiousness and brutality is well caught too. A problem for the modern reader and viewer will probably be Mr Knightley who is an older man who longs for a girl he thinks would never be attracted to him; their relationship is based on congenial natures, respect, trust, and high intelligence too. John Carson is as close to Austen’s Mr Knightley as one can get—and he is attracted to Emma sexually. Like a number of the actors in the early adaptations, he was a stage matinee idol type and some shots capture his beauty when a younger man:

In daring full dramatization of the Christmas scene where Mr Knightley and Emma talk over the small body of litte Emma, this film has Mr Knightley visit Emma nursing the baby upstairs, and a strong sexuality attached to a coming family is conveyed by postures, dress, and gestures:

(‘72 Emma)

(‘72 Emma)

There are three other Emma films to see. One free adaptation is well-known and has been discussed and perhaps overpraised widely: Amy Heckerling’s comic 1995 Clueless. It’s worth far more comment than I can give it here. It does imitate analogously step-by-step a backbone outline of Austen’s Emma, eliminating only Jane Fairfax (its tragic heroine in potentia), for the schoolteacher, Miss Toby Geist (Twink Caplan), doubles as poor Miss Taylor that was and Miss Bates. It sort of lays bare and justifies those films where the emphasis is Harriet, for Heckerling replaced Jane Fairfax with with a congenial close friend, Dionne (Stacey Dash). None of the crucial hinge points of the original were omitted. There’s a displacement of the insult scene: Tai (the Harriet character, Brittany Murphy) has grown so big and filled with conceit that she mocks in front of others Travis (the Mr Martin character, Brecklin Meyer); this makes Emma (Cher, Alicia Silverstone) less obnoxious for none of her insults are shown to be felt by those she dismisses (she does this behind their backs).

Nonetheless, Clueless is, despite having been made by a woman, written by her, much less woman-centered and feminist than Ruby In Paradise (a free adaptation film by Victor Nunez); we have much less of a “women lovely woman reigns alone” film as Cher’s father is all-powerful, Cher is contrite and really mends her ways (as Austen’s Emma does not) and submits (in suddenly modest outfits) to be taught by Josh (our Mr Knightley, Paul Rudd, her stepbrother who is not a blood relation).

These things have been noticed; what is not so often noticed is how the film-maker does bring in Emma’s mother through the picture on the landing and at least by visual icon suggests the emotional melancholy depths of the book all too often ignored. The movie shed light on another book I’ve connected to Emma all along: Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe13. In both Emma and Udolpho, the missing mother is central to the story’s power. We can also bring in Northanger Abbey and the missing mother there, and there we have the picture on the wall which becomes part of the action (as in Clueless and Udolpho). There is no picture of Emma’s mother; she paints a poor picture of Harriet (and influences her badly).

A touching scene: Mr Wendell Hall (Wallace Shawm) brought together with Miss Geist as Cher & Dionne look (‘95 Heckerling Clueless).

The second and third are Robin Swicord’s The Jane Austen Book Club, based on Karen Joy Fowler’s book. I leave my reader to read my full blog on that one. The other, less well known, Whit Stillman’s Last Days of Disco combines elements of Sense and Sensibility with a central character modelled on Emma and played by Kate Beckinsale.

We see Charlotte (Kate Beckinsale) working in the publisher’s office with Alice (Chloe Sevigny) at the desk behind; they take an apartment together and behave something like sister-friends (‘98 Whitman Last Days of Disco).

It’s a gem of a movie, intelligent dialogue, and a humane commentary on Emma’s often cruel behavior, here explained as part of an aggressive and determined-to-succeed personality, one not ashamed of her values. Whitman’s free approach to adaptation allows him to have his Emma-Charlotte (Beckinsale) apologize humbly to Alice (Chloe Sevigny) after Charlotte cruelly mortifies Alice by saying before the assembled group of friends that Alice has a venereal disease. Charlotte is scolded by her boyfriend, Jimmy Steinway (Mackenzie Astin) in true Mr Knightley vein: “How could you, Charlotte?” A few scenes later in a moment of intense emotionalism, Charlotte (as Elinor to Marianne) reveals to Alice a side of her experiences she had kept hidden from Alice: Charlotte had thought she was pregnant and looked forward to telling the father, Jimmy, assuming that Jimmy would rejoice, only to discover Jimmy was on the point of proposing breaking up (he’s really no Mr Knightley, rather a cad-like Frank Churchill). Charlotte’s psychosomatic pain lands her in hospital and she sings “Amazing Grace” self-referentially, beautifully, and with great humility.

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

This moment becomes a comment on Austen’s character Emma who far from humbling herself and apologizing at the close is complacent by the novel’s end and yet is showered with rewards.

Of course all the films also are alike. One motif which binds them all is that of Mr Knightley rescuing the woman Emma has misplaced or hurt.

Miss Bates (heart-achingly performed by Sophie Thomson) asked for the honor of her company in a walk seconds after Emma has humiliated her (‘96 McGrath Emma)

I’m one of those uncomfortable with Austen’s Emma. I don’t see what Emma has done to merit the apparently happy ending she is rewarded with. It may be that Austen is just showing how such a woman, so handsome, clever, rich, now with two comfortable homes, and a complacent disposition will live with ease. If so, I wish she hadn’t spent so many final chapters detailing the wish-fulfillment element and cannot myself believe that Jane Fairfax could so quickly forgive, unless again we are to see status at work and Jane’s reserve still functioning to protect her. This seems a stretch in that “feel good” scene between them in the corridor of Miss Bates’s lodging. What may be said, as Margaret Drabble writes, is “society has triumphed,” and I would feel more comfortable if the irony directed at the final happy community were shafted by someone other than Mrs Elton.

Juliet Stevenson a much softened Mrs Elton (‘96 McGrath Emma)

Next up: Northanger Abbey

1 Mansfield Park, Pride and Prejudice, and Sense and Sensibility. “Important” is such an overused word that it may seem beyond retrieval as a meaningful word (publishers scream from the top of their blurbs how this is an important, that an essential book), but its simplicity (it’s not pompous) makes me reach for it.

2 Pinch uses a point of view and philosophical material she developed in her book, Strange Fits of Passion: Epistemologies of Emotion, Hume to Austen; this book includes chapters on Austen, Radcliffe and Charlotte Smith.

3 Alas, unlike the new Penguins for Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park, this Emma does not print Tony Tanner’s brilliant essay on Emma—where he brings out some perplexing oddities of the book; its playful and intense sexualities (all displaced); its claustrophobia, the characters’ sense of oppression and restriction, its narrow purview even if complexly presented. Thus this new Penguin is not as valuable as the other new Penguins; Stafford closely she sticks to Chapman’s 1923 text.

4 To name but a few: those have introduced editions with this kind of fanfare, Lionel Trilling in the 1957 Houghton Mifflin Emma, Ronald Blythe in the 1966 Penguin Emma (in his cliched language, a “climax of … genius and Parthenon of fiction”); in book chapters, there’s W. A. Craik’s Jane Austen: The Six Novels (her “finest achievement”); A Walton Litz, Jane Austen: A Study of Her Artistic Development (“deepest” book).

5 See Female Communities, 1600-1800: Literary Visions and Cultural Realities, edd. Rebecca D’Monte (St. Martin’s Press (2000); it includes essays on the fiction of the women in this Bath circle; Mary McKerrow, Mary Brunton (Edinburgh: Orcadian, 2001); Joan Hinde Stewart, Gynographs: French Novels by Women of the Eighteenth Century (Lincoln: Nebraska UP, 1993).

6 See Walter Scott, “Review in Quarterly Review, 1816, Jane Austen: The Critical Heritage, ed Brian Southam (New York:Barnes & Noble, 1968):1:63-64; a comment reinforced in his diary where he talked of how he can do the “bow-wow” and grand landscape style but not this sort of character creation and excitation and spirit and originality of perception.

7 Wayne Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago: Chicago UP, 1961):243-66.

8 See Kate Trumpener’s “The Virago Jane Austen,” Janeites: Austen’s Disciples and Devotees, ed. Deidre Lynch (Princeton UP, 2000:140-65. Two recent ones are Bobbie Ann Mason’s In Country and Valerie Martin’s Mary Reilly. It’s characteristic of many of the early 20th century novels by women published by Virago

9 James Austen-Leigh, A Memoir of Jane Austen, ed. Kathryn Sutherland (Oxford, 2002):119 (Chapter 10).

10 In my view the very best introduction to Emma, thus making the inexpensive edition valuable and an excellent buy is the Signet with Margaret Drabble’s frank introduction (first printed 1964 and still in print). Kettle and Schorer are reprinted in Jane Austen: A Collection of Critical Essays (NY: Prentice-Hall, 1963):98-124; Avrom Fleishman’s “Two Faces of Emma” is found in Jane Austen: New Perspectives, ed. Janet Todd (NY: Holmes & Meier, 1983):248-57.

11 I also recommend the Longman edition for its reprint of documents about slavery and governessing; a great deal of fuss is made about a discussion that never takes place about slavery in Mansfield Park; in fact in Emma we have direct references to slavery, Bristol (part of the triangular trade, a horrific place for slaves) and a comparison of this trade with one of the few respectable occupations available to unmarried gentlewomen: the miseries of governessing. One can see a change in fashions by comparing the two Nortons. Both edited by Stephen M. Parrish, the 1st in 1972, and the second in 1993. The 1st contains only one essay by a woman, and none of them bring up the woman-centered or proto-feminist material of the book nor its political stance; in the 1993 book 6 of 15 essayists are women and the debate is over where Austen stood politically, how we are to take its presentation of a apparently powerful and aggressive heroine (as in the chapters from books by Mary Poovey, Marilyn Butler, and Claudia Johnson).

12 See Tom Hoberg, “The Multiplex Heroine: Screen Adaptations of Emma,” Nineteenth-Century Women at the Movies: Adapting Clasic Women’s Fiction to Film (Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1999):106-28; Louise Flavin, Jane Austen in the Classroom: Viewing the Novel/Reading the Film (Peter Lang, 2004):123-34.

13 A black morning: Kristevan melancholia in Jane Austen’s ‘Emma.’. Frances L. Restuccia. American Imago v51.n4 (Winter 1994): pp447(23). (8033 words).

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Penny:

“I have all the Penguins. Which is better, the Oxfords or the Penguins?”

I reply:

In general, the new Penguins are the best ones for the texts right now; the slightly older Penguins are very good too. The newer Penguins sometimes have the better introductions. The best new Oxfords are those which include Tony Tanner’s essays; the S&S which includes Margaret Doody’s introduction (the only feminist piece allowed to stand, the others have all been replaced; we are not allowed to have any intelligent feminism criticism unless it's by a super-prestigious scholar) and Mansfield Park with Jane Stabler's introduction are good buys too.

I like Margaret Drabble’s introductions for the Signet; so too some of the older Signets have excellent introductions (by, e.g., Patricia Meyer Spacks). They are $4.95. Someone in that company has intelligence, and the new Signets include afterwards by women who write popular romances, and these are revealing (and sometimes unconsciously funny). For example, the recent P&P introduced by Drabble has an afterward by Eloisa James. James berates Elizabeth for hiding from us that she is dying to get married, that it’s her first thought. That’s ludicrous. Elizabeth Bennet is not a person hiding her thoughts from us. It shows how pop romance writers think and perhaps their readers too. The Afterword in the Signet Northanger Abbey is, however, simply ignorant. Stephanie Laurens has never read a gothic or Radcliffe; she calls these novels "sensational" (a Victorian type) and likens them to "soap operas." It's disgraceful such a misleading piece should be published by a respectable publisher.

The only Oxford that stands out from among the “half-way house” type editions is the one that includes Lady Susan, Watsons and Sanditon with Northanger Abbey—because it includes these three. I think an older Penguin (with Drabble’s introduction) for lady Susan, Watsons and Sanditon may be out of print you see. However, the introduction by Claudia Johnson is wrong. It misdates Lady Susan making it easy, and it is dismissive of The Watsons. We don’t know that Austen abandoned The Watsons. Naturally when she began to publish, she chose the complete or more complete texts. Had she lived, she might well have returned. And it’s in a far more finished state than Sanditon.

Some of the books with fat apparatus are worth it, but they are highly uneven. I have tried in each of my postings on these new editions to say which ones are the best and why.

Ellen

— Elinor Sep 24, 7:15am # - From Diana B:

“Your big Emma project looks so handsome too.”

— Elinor Sep 24, 8:19am # - From Elissa:

“Hi Ellen,

Just had to take a moment to tell you how fascinating I found your recent blog – how you keep all those filmic productions in your head I have no idea!

Must say you surprise me with your identification with poor Fanny P. – I would have thought you might identify a bit with Anne Eliot. And I don’t care about the consensus negative review of Gwyneth as Emma – I think she’s just great in the role …

Elissa”

— Elinor Sep 24, 8:49pm # - From Tom:

“Your most recent EMMA post is terrific. Thanks for it. Did you know Tanner’s JANE AUSTEN appeared as a “reissued edition” in 2007 with Palgrave/Macmillan? Marilyn Gaull provides a not uninteresting preface; John Wiltshire a low octane “note on the text”. Perhaps you’ll have a look. We agree, don’t we, that Tanner’s is a very fine book/collection.

In the office, must go for now –

Best to all— Tom”

— Elinor Sep 25, 2:09pm # - From LA (Laurel):

“I think that you have surpassed yourself with this one. The text and images are stunning. Quite an accomplishment. I am awed and I am sure readers will be too. What a fabulous resource for readers and significant to have all six novels covered …”

— Elinor Sep 25, 2:11pm # - Just to say congratulations to both you and Laurel on another great pair of blogs – I’ve recently acquired a DVD of the Andrew Davies adaptation and also a “making of” book about this version, which I spotted in a second-hand shop, so will soon be revisiting it.:) I’m afraid I have all the film and TV versions mixed up in my mind, although that is the perfect excuse to watch them all again…

— Judy Sep 25, 4:40pm # - To late for this blog I've discovered by mistake I bought a 10th edition of Emma. I had had 9 plus one French (by Josette Salesse-Lavergne) and one Italian (by Pietro Meneghelli) translation. As of today I have 10 copies of Austen's Emma in English.

I meant to buy what looked like a collection of new essays on Emma and discovered this “case study” put together by Alistair Duckworth is a Bedford & St Martin’s series of editions of famous novels followed by a very generous and thick selection of relevant contemporary documents and good criticism (some of them brand-new and written for this volume). As his book on Austen (The Improvement of the Estate) is, so Duckworth’s introductory essay to Emma sound and perceptive. The text is based on Chapman’s edition of the 1816 first edition. The documents are well-chosen and a little unusual, e.g., the song of Robin Adair that Jane plays; Robert Southey on behalf of repressive policies. Duckworth has chosen some of the best recent critics and framed their essays with essays on what is gender, marxist, cultural, feminist, new historical criticism. The frontispiece of a contemporary painting by John Constable of Malvern Hall is appropriate.

We cannot have too many texts of Emma!

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 25, 10:11pm #

commenting closed for this article