Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

BSECS Jan '09: Life-writing (2) · 23 January 09

Dear Friends,

My second blog on the conference I attended at Oxford, and the third and last on Jim and my trip to the UK this January. Thursday, the 8th, the last day of the conference, I went to three sessions, and the plenary lecture. Here I cover womens’ memoirs (by Madame Roland, Charlotte Bury and Catherine Carey of the court of Queen Caroline); womens’ country house poetry and Johnson’s poetic ideals (and those in his prose, especially in the Life of Savage); virulent anti-women depictions of women biologically and in the public sphere, Cleland’s Fanny Hill; and an informative talk on Anglo-Indian lives and how to write effective accurate history using biography; Charlotte Smith (once again, I can never leave her out); and some French art (ditto).

The first session I went to, “Writing Lives and Judging Character: The Ethics of a Genre,” was of the same high quality as the first session I attended on Wednesday about Montagu, Scott, & Barbauld, or the mid-, and late century Bluestockings. The title was less frank since the first two papers were on women’s memoirs. Sian Reynolds discussed Madame Roland’s memoirs and letters. Her idea seemed to be to show us that Roland did not think strategically at all, but saw politics as a moral arena. Instead of admiring Roland for her passionate ethical sincerity (which I do), Reynolds seemed to disrespect Roland for her lack of effectively calculating careerist behavior.

The Elibron reprint of a 19th century edition of Madame Roland’s powerful memoir, first published in the 1790s after her death

Reynolds began by telling us that Roland had thought she did not need to flee, as she did not imagine she would be imprisoned, much less guillotined. When she realized, she would probably be murdered, she wrote her memoir in a kind of furious white heat. Her book is fragmentary: the first version she wrote on school books was destroyed, the second (the one we have) consists of 3 parts: an appeal to a (supposed) impartial posterity (a political memoir to set the record straight); a section modelled on Rousseau where she tells of her growing up (Reynolds did not mention this, but here is where Roland describes how as a girl she was molested by her father’s apprentice; it is the most powerful section of the memoir where we learn of Roland’s love of reading, and her ideals and early sexual life, her love of writing letters); a section of character sketches modelled on La Bruyere.

Reynolds’s paper concentrated on this third section, which is often neglected: she included the character sketches of Du Gras; Danton described as repulsive with a ghastly face, uppity from his upright stance, passionate, jovial in company (Roland realizes how wrong she had been to dislike Danton); Brissot who was Roland’s lover; Condorcet (Roland is harsh on him & says his character never rose above fearfulness); Robespierre (Roland thought of Robespierre as passionately dedicated to liberty). The early sketches are carefully & judiciously written; as Roland writes on and drew near to death, she gets desperate and writes yet more in the hope of reaching others. As Rolland waits to be guillotined, we watch her prepare herself to make sure she enacts a dignified death.

In the discussion afterwards it emerged that Reynolds also thought Roland communicated to the world through writing, & (again) did not respect her for this. Talk, it was implied, is superior to writing. Reynolds said that Roland saw as her predecessors Catherine Macauley & Tacitus. Roland did herself love Rousseau and especially his Julie, ou la nouvelle Heloise. Again Reynolds was critical of Roland for telling her husband about her love for Brisset, and thought she got the idea from Rousseau. However, the first instance of the adulterous wife telling her husband out of integrity is found in LaFayette’s La Princesse de Cleves. For my part I feel strong sympathy for a woman who was naively idealistic in comparison with often cynical male memoirs & novels of the era and I suggested this move (to tell your husband about your love for another man) came under discussion in many women’s novels and memoirs where it was not dismissed as silly, but seen as meaningful for the woman. I asked about editions of Roland’s many letters and elicited the information that there is a standard and good four-volume edition in French. I own only a 19th century selection of her letters.

Amy Kelly discussed two memoirs from the court of Queen Caroline, both by women: Charlotte Bury’s Diary Illustrative of the Times of George IV (1838) and Catherine Cary’s Memoirs of Miss C. E. Cary (1825). Bury’s memoirs caused vitrolic debates in the press because of her candid exposure of real personalities. She was read because she was close to the powerful people at court at the same time that she was distrusted because she was close to the corruption. Bury explores what happened at court during the period she was there, and weaves character sketches and dramatic scenes into her text; Bury also intersperses her narratives with vignettes of her friends and associates dying. By contrast, Carey’s memoirs are written by an outsider, and she writes as an exile & victim. Carey writes about the queen and shows that Catholicism was an issue. In both memoirs the language of sensibility, a community of taste, the conventions of gothic fictions are central. Romance and political narratives intersect with real danger coming from politics. Kelly suggested Bury’s memoir is comparable to silver-fork novels, and, alas, both became negative touchstones for memoirs by women. They were what no respectable person would write.

In the discussion afterwards, someone suggested that the memoirs of both women (?) have a high theatrical quality. Kelly thought that for Bury personality in politics is political; she asserted that individuals are responsible for a certain level of choice and by their choices they act politically.

Kirsten Jenson had a consistent argument. She defined the Theophrastan character as one invented in the 17th century and rising to a full blown type in La Bruyere. Such a character sketch provides a social typology with a strong ethical inflection. We see how character is built out of habits. Jenson thought people were using the theophrasan character sketch as a tool of analysis of self and a catalyst for reform. She then went through characters & life-writing from Addison to Johnson. Jenson thought William Law’s Theophrastan characters were influential. She outlined three periods, the first early 17th century, the second in the 1640s when great numbers of characters appear in writing (during the French civil war).

It emerged in talk later that the problem with Jenson’s thesis is portraits are so similar to Theophrastan characters, and these are written for a variety of reasons, sometimes commemorative, sometimes because the author wants to show he or she knew famous people, sometimes to set a record straight as the writer knew the person, sometimes sheerly as a type of appealing writing.

My second chosen session for Thursday morning was Poetry and Poetics #2. The first paper given was by Sharon Young, “Women’s country House poetry.” She covered Anne Finch’s “Upon my Lord Winchilsea: and “To Lady Worseley” and Ann Ingram’s “Castle Howard.” (See the texts and my commentary.) Young said it was female patronage and networking that first gave rise to Anne’s poems, and for both women argued that there are complicated political ideas in the poems. She implicitly denied the personal content. You’d never know Anne’s poems are intensely sad. She was highly applauded when she’d done—as if she had done something important for women’s poetry. The reality is that she showed the bland stereotypes in ideologies in emblematic language.

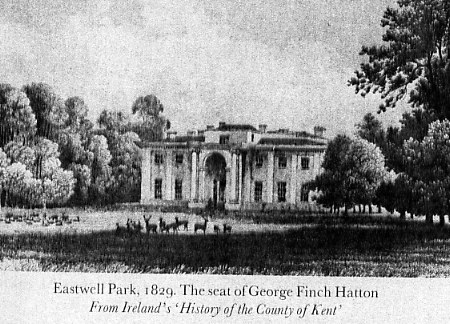

The house Anne Finch moved into in 1704 and wrote about idyllically in both deeply melancholy & comic veins

Among the more disquieting tendencies of this conference (something I saw at the MLA last year for early modern women) was the strong tendency for people to find male patterns and values in women’s writing and acts; then you see they are valuable. (This made me remember Paula Backscheider’s book on 18th century women’s poetry and value it all the more.) I & others have written long papers showing that disquiet and depression are the core experiences for Anne Finch, and these three poems were strongly primarily personal. Mary Leopor’s Crumble Hall was instanced in the talk; it is comic and impersonal, and celebrates the hall—from the point of view not of someone related to the rich man or people who run the place, but from a servant’s point of view. Therefore it was declared different from the three under discussion. Again the criteria is public, typically male.

What Young did was take a genre women wrote in frequently, the country house poem, a retirement and friendship poem in women’s hands, and turn them into poems about publicity, networking and politics. She admitted that most of these women never got anything (tangible is the idea) in return. Aemilia Lanier’s “Description of Cookham”, dedicated to Margaret, Countess of Cumberland and her daughter Lady Anne Clifford, was cited as an example where the poet got nothing for her efforts. Sheer friendship was not seen as enough of a gratification for poetry to be written.

Richard Holmes’s paper was on James Arbuckle’s “Glotta,” a long poem written in the tradition of Denham’s “Cooper’s Hill” and Pope’s “Windsor Forest.” Holmes wanted us to see dynamic allusions in this hitherto thought dull and obscure poem. Arbuckle was celebrating Scotland in an English and implicitly Jacobite form. Arbuckle proposed Buchanan as the great poet of Scotland. A few Scots people in the room seemed impressed.

Samuel Johnson by John Opie

The third paper was the most moving I heard in the conference. Timothy Erwin discussed Johnson’s poetry and prose, and found in it high ideals. His central text was Johnson’s Life of Savage, and instanced a crucial moment where after Savage has been pardoned for murder Savage divides the tiny amount of money he has with someone who needs it badly and testified against him. Like famous emblems of compassion and selflessness, Johnson wants the reader to forgive Savage. Prof Erwin thought the implicit text criticized by Johnson was often Pope’s Dunciad, and that Johnson turned away from Pope’s elaborate and phrasal pictorialism.

In the discussion afterwards someone summed up, seemed to me to reduce Erwin’s idea by saying Savage was a holy fool in the incident after his pardon. (This was not a conference where any idealism was taken seriously or much respected.) The point Prof Erwin was making was that Johnson is even-handed over Savage; Johnson makes Savage emblematic of the compassion Pope lacked, though Savage never saw his real state. What was said to be Johnson’s avoidance of the visual was said to be part of the limitation of his poetry. On the other hand, Johnson’s austerity, feeling that pictures were incapable of saying something generally useful, and feeling that poems like Goldsmith’s “Deserted Village” did right to show us how de-peopled the rural landscapes of England and Scotland were becoming were all defended.

After lunch, there was one session left and then the closing plenary lecture. I went to the session titled “Loose women: Depictions of Female Sexualty in 18th century print culture.” The first paper by Jennifer Sarha on John Cleland’s The Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure reminded me of Eva Gonzalez’s on the Marquis de Sade’s heroines, Justine and Juliette, the day before: like Gonzalez, Sarha read in a flat monotone. Sarha overtly artued that ugly pornographic and cruel scenes (one of sodomy used to humiliate the heroine) was used in a moral text. She summarized three positions on Cleland’s novel thus far: that it was immoral and pornographic; that it is misogynistic; that it is homosexual. She implied all these positions are false and that the text is for companionate love, and pleasure, very jolly. I’ve read that Andrew Davies’s film adaptation turned Fanny Hill into a merry romp; so I suppose we might say it was a faithful film.

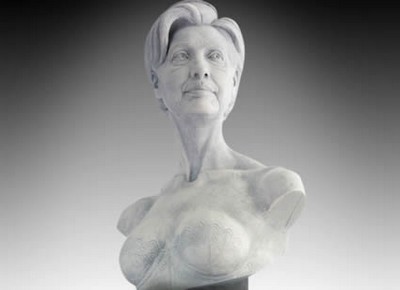

The second paper was one of the best I heard. Corinna Wagner showed how women who enter the public realm were depicted in debased and cruel ways; how their biology was made the target of vicious attacks. Her paper and set of illustrations included the pictorial depictions of Marie Antoinette in the period vilified her destructively. We saw really disgusting caricatures of Antoinette having sex with women, pictures which debased her as so many graphic body parts. The real woman was erased. She showed Gillray (who is awful) cartoons, cartoons of ugly women giving birth to horrible babies, having monstrous breasts (the Duchess of Devonshire was depicted breast-feeding a literal fox while her children go hungry). Women were turned into animals. The most striking image she showed was a modern one, Daniel Edwards’s bust of Hillary Clinton which accentuates her breasts.

Daniel Edwards’s 2006 bust of Hillary Clinton

The last paper, by Darren Wagner, was on the pathological imagery used to depict women’s biology from the early modern era through the later 18th century. Again we looked at images of women made bestial, devouring, , their body parts turned to repellent perverse uses which were linked to childbirth and sex. For example, a Hogarth engraving where a woman gives birth to many rabbits. The only depiction of women’s sexuality as something normal and not frightening, and at all accurate was William Smallie’s 1754 set of anatomical fetuses in the womb. He also cited novels, e.g., in Tristram Shandy we find a farcical treatment of the womb and male anxiety over women’s sexuality.

As in the session the day before on “Turkey,” the talk afterwards was informative, insightful and took into account the connections of 18th century thought and pictures and 20th/21st century ones. It emerged that the title of the session, “loose women” had not been thought out: it was not really appropriate to the content of the talks. We discussed how only in the last couple of decades do you see anal intercourse presented as part of common sex life without making it horrific. It was suggested that the dislike of giving women power came out in the way they were depicted breast-feeding. (I thought to myself that the pressure to breast-feed might be proved to be a way of forcing them to remain in the private world when you looked at how breast-feeding and breasts are used in comic and other depictions of women.) We discussed Daniel Edwards’s bust of Hillary Clinton at length and people suggested that it was not a complimentary depiction of her as powerful, but rather made her distasteful.

The plenary lecture, Margot Finn’s “Anglo-Indian Lives in the Later 18th and Early 19th Century,” was excellent, but (as so much was throughout the conference) implicitly political conservative in that we were urged to accept colonialist behavior as simply the way individuals fought to get ahead, grow rich, live well. Margot Finn’s 45 minutes was packed with information. Basically she defended an old-fashioned biographical & narrative approach to history as the most accurate and insightful way to present & to understand actual experience. Her project is to write a socio-economic picture of the Anglo-Indian world through studying individual colonialist lives between 1757 and 1858 (the years of the two famous massacres). Females will emerge as important and active in their kinship behaviors. In effect, she is exploring the British empire through collective family biographies, testing (as she put it overarching ideal by realities.

Part I of her talk was a history of how biography fell out of favor with intellectuals in the 20th century, partly as a result of the Marxist perspective. Again (a common theme in the conference as I’ve said) Edward Said’s book came under attack. Prof Finn cited as important for bringing biography back into respectability Thompson’s Making of the Working Class, Natalie Zemon Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre, the work of LeRoy Ladurie, and said the popularity of books like Dalrymple’s White Moghuls and Linda Colley’s book on Elizabeth Marsh were showing how delving deep into an individual life in the context of the sociological and political realities of an era were fruitful and could influence readers’ thinking. She was not for the older tradition of exceptional lives as found in the ODNB but said we should not dismiss this tradition.

In Part II of her talk she reviewed the dozen families she is studying and then focused on the Monroes, a middle class Scots family which went bankrupt and then worked hard to retrieve its money, power, and position by sending sons to India. She concentrated first on Sir Thomas Monroe born in Glasgow 1761, 1779 joined as a cadet the Anglo-Indian war, a scholar of oriental languages who rose high in the administrative hierarchy and started a policy of giving Indian’s land in return for their cooperation with the British. In 1814 he went to and returned from Scotland with a wife, in 1827 he died of cholera. India became a launching pad for just about all his brothers. Daniel accused of murder was sent to India. James was propelled into medicine because he could get a place as a doctor in India; he had not wanted to go out to India, but was forced to to get money for himself and the family. He sickened there & came home to die rather young.

It was revealing to see how men were forced to do things to get wealth for the family in the way women were coerced into marriage and how the money acquired with such difficulty and at such a price was often not enough to make the family rich and high in rank. Each son would remit money to the family to help the sisters get into high society and husbands who were of as high a rank as they could get, but we find daughters working as painters to make money, designing calico and sewing. One daughter made a good marriage the second time (good meaning she married up); a daughter was sent to India to get a husband and eloped with the younger brother of an English banking family. One son died in a duel over his wife’s lover.

Deferred marriages led to illegitimate children as well as the men having relationships with Indian women. The stories of the lives of two illegitimate children reveal how a woman’s reputation for chastity actually counted more than her racial heritage in gaining respect for her child and a decent life. So one daughter, Mary, the child of an Indian woman, was brought up within the family (quietly) and married off to a white man; the other, Jessie, whose mother had been white but not chaste, was put out to work and kept far from the family and led a probably hard and despised existence. Typical of the conference Finn made no judgemental comment on this whatsoever.

The Monroe family letters contain political commentary and debates, showing that the men held mostly reactionary nationalist and colonialist attitudes, and that when they came home to live later in life, they were uncomfortable amid the more liberal attitudes they found at home. One son wrote of how he was an alien in India, but in Scotland he had lost his identity as a British man. These letters she quoted were among the most revealing moments of her talk, and she concluded by saying Scots and Irish people were heavily represented in the colonialist families, and arguing that her approach would lead to accurate histories which were vibrant and truly educational reading.

The talk afterwards showed that feminism is not dead altogether, though in this conference the word was only used in a denigrating way by males referring to an apparently obsolete and obtuse group of increasingly isolated women with exaggerated ideas about everything. Not one woman protested. (I didn’t either; who would dare buck this dominating assumption?) The feminism that was allowed was not socialistic, but individualistic and for power. Again what was sought were instances of women behaving like men and having men’s power. So I sat for a number of minutes while people talked of how wills proved that the women of the Anglo-Indian families owned substantial amounts of stock in their own names, were ruthlessly active in patronage networks, managed households in Europe and were glad to marry for money and pressure other women who might not have wanted a particular husband to marry him anyway.

An actual popularly sold modern biographical memoir of Anglo-India in the womens’ memoir-writing tradition

Interestingly, one man objected to the citation of White Moghuls as a book which showed the respectabilty of biography: he said we all know the reason it sold widely was its sex scenes. Another person objected to the use of the term biography as suggesting we were returning to Victorian biographical traditions. To me the best part of the project was where it was coterminous with Trollope’s angle on colonialism in his stories and travel books: the injustice of social and economic arrangements at home led the middle and working class people in Britain to risk life and give up much just to make ends meet and live more decently than they ever could have in Britain. Yes, they had to wrest what they had from the poor elsewhere, but it was not much fun, in fact involved much hardship and often ended in failure.

As I thought about this I got up to get my bus back to Jim.

I did get into conversation with one friendly graduate student towards the end of the day. Just before the plenary lecture began, I was walking in the main hall and tired. I saw no place to sit. A young woman sitting on a wide seat moved over and gestured to me to join her. We began to talk and it quickly emerged that she had been having a not so happy time because her subject is Charlotte Smith. When she would mention this great poet and novelist, a strongly radical woman, she would get blank stares. Yes Charlotte Smith was not an ideal woman for this conference, though she was no feminist. I told the young woman how I loved Smith, how I’d read her poetry, made a foremother poet posting of Smith and put it on the Wompo festival website, how many readers her poery had gotten, how she was a major figure in Backscheider’s book, and when we compared tastes, she was delighted to discover that I too have read Ethelinde and it’s actually my favorite among Smith’s novels.

Charlotte Smith as depicted by George Romney (1792)

We exchanged email addresses, and said we would get in touch after the conference. I’ve learned that this kind of conversation hardly ever leads to a friendship on line afterwards; at most one gets a brief email acknowledging a conversation and tthat’s it. I’ve invited people onto my lists, but cannot remember any one ever taking up the invitation. Still I hope I encouraged her and made her feel better. She was not alone in her love for this revolutionary unconventional idealist and embittered melancholy woman.

After all the real purpose and happiness of a conference comes from contact with those who share your deepest interests, for a sense of belonging to your tribe. And that was had at this conference in much of the talk in and outside the sessions I was not able to register.

And so my notes for this conference come to an end. There is nothing surprizing in the strong conservatism that has emerged in the academy since the death of deconstructionism. After all who rises to high positions in colleges; most of the time people from upper middle class families, especially in Britain. One can qualify what one heard in public papers by remembering that privately people might feel differently and keep unconventional ideas to themselves lest they offend someone and hurt their careers. In the dinners and lunches in the dining hall I got into good talk with people who evinced liberal and thoughtful attitudes in all sorts of areas, including that of women’s issues. One man talked of how corrupt the US college promotional system is, even worse he said than the British. Another talked of the dumbing down and commercialism going on increasingly in British colleges. People were far friendlier in these eating fests than I’ve seen them be in American versions. I talked at length to one man who had visited the US (driven through California) and we compared notes about class snobberies, capitalist underpinnings of public events, exclusionary practices in the US and UK. And not all the papers were conservative and many were if not socialistic feminist, about women and women’s writing.

A real lacunae was art: there was but one panel where the visual arts were discussed, and only 2 of the papers were actually about visual art. I met an art historian doing her masters thesis who was very friendly and she told me repeatedly how disappointed she was in the lack of art papers and the quality of the papers in general in comparison to papers she was used to at art conferences (especially it seemed to her by those in higher positions). There were few French scholars: ASECS usually has both quite a number of art panels (on pictures, architecture, landscaping, sculpture) and quite a number about the French Enlightenment and in French. The conferrence showed that most British scholars of the 18th century are literary and study British letters.

Francois Boucher (1703-70), The Water Mill (1750s)

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- When you spoke of Sharon Young: “She admitted that most of these women never got anything (tangible is the idea) in return. Aemilia Lanier’s “Description of Cookham”, dedicated to Margaret, Countess of Cumberland and her daughter Lady Anne Clifford, was cited as an example where the poet got nothing for her efforts. Sheer friendship was not seen as enough of a gratification for poetry to be written.” I am strongly reminded of how the writing you have done on the internet, all the time and love you have put into it, is similarly devalued because it doesn’t bring in money. Anything done nowadays that doesn’t bring in money is devalued.

— Jill Spriggs Jan 24, 7:30am # - From Victoria on Anglo-Indian films:

“Michael Wood hosts a 5-part series on India this month on PBS (book and DVD available); the installment on the Sepoy Uprising aired last night, and its focus featured an angle rarely seen: Indians’ perspective on the uprising, then and now. Many view the event as part of a long, heroic tradition of Freedom Fighters (their term); others are proud of their family heritage of loyalty to the British in 1857-58. Revealing also is the exploration of mutual culpability and the role played by religious beliefs. I recommend that installment for a class and also add a title to the film list: The Flame and the Arrow.”

— Elinor Jan 24, 7:57am # - Dear Jill,

One irony here is that no one gets paid for going to a conference, nor doing a paper. University departments will defray part of your costs but usually not the whole of it. Of course, the people there are building what Bourdieu calls social capital, the advantage is in the networking.

However, I did notice that there were a larger number of independent scholars (people who are not employed by any institution that’s academic) than I usually see at such conferences. Mostly older women. Now they are there for the experience and knowledge. So too established scholars. Johnson said something like a person who doesn’t write for money is a blockhead, but he himself spent a large part of his life in doing low paid scholarship. His pension kept him solvent & comfortable.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 24, 1:05pm #

commenting closed for this article