Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECs, Richmond: women writers & women's issues · 15 April 09

A recent picturesque landscape cover for Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho

Dear Friends,

The second type of session I went to at ASECS, Richmond, was about about women writers: on individuals like Jane Austen and Ann Radcliffe, actresses as autobiographers, and writers on education (Mary Wollstonecraft and Anna Barbauld); to these I’ll add some good individual papers I heard on women’s issues.

First, individual geniuses and what used to be called “scandal” and are now being called celebrity memoirs:

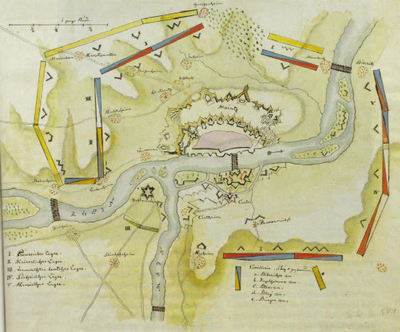

The first session I went to was on a poetic genius much beloved by me: Ann Radcliffe, and the idea was to discuss her non-gothic writing (Thurs, 8:00-9:30, Ann Radcliffe: Beyond the Gothic). I had read that Angela Wright had not shown up, and was delighted to learn that her paper on Radcliffe’s A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 would be read aloud by someone else. I’ve read this superb travel book & have thought of writing a paper on it. The argument of Wright’s paper was the book is a travel memoir written at the height of Radcliffe’s powers. We see her gifts for the picturesque at their strongest, and (I know this to be so) it shows that the view of her as conservative is wrong. Apparently the reviews at the time did not talk about the book’s serious subjects, but rather focused on her visual artistry. Wright showed Radcliffe was anxious lest she be perceived as narrowly nationalistic in the way Smollett is; that Radcliffe shows intense dismay over the results of war & sieges, that she recalls the English poets and provides passages of intense tranquil reverie, descriptions of castles, mountains, forests, talks of poor people, soldiers, and interweaves pasages from the tragic Johnson, melancholy Shakespeare, visionary Collins.

The Seige of Mainz, 1793, a contemporary image

A map of the seige, one is included in Radcliffe’s book too

The 2nd & 3d paper found non-gothic contexts for Radcliffe. JoEllen Dulucia’s paper was on Radcliffe’s writing & the Scottish progress poem. She suggested we should see Radcliffe as also a descendent of Ossian and Scottish romanticism. She placed Radcliffe against a tradition of Whiggish and liberal attitudes found in James Thomson’s poetry: Radcliffe is anti-imperalistic and moves into an inward private world, sees the rise of power as a decline of what makes English society worth living in. Prof Dulucia thought Thomson was ambivalent about the British state, and Radcliffe celebrated the past, rural countryside, and while allured by distrusted the then modern beauty of Venice. Udolpho is like a progress poem as Emily travels from place to place, a number of epigraphs are taken from Thomson’s poem, Castle of Indolence. In Mysteries of Udolpho Emily is a victim of history, of supposed progress (social life is not much fun); she stands at a cross-roads of conflicting choices. Jayne Elizabeth Lewis studied and analyzed the uses of the word & idea of “air” in Joseph Priestley and Radcliffe’s writings. Both of them were naming and describing things not named or described before.

The discussion afterwards was lively and revealing. I brought up how while Radcliffe was not writing out of an anti-Catholic point of view, she was deeply humane instinctively & for individual liberty & safety: she disapproved of convents strongly, was aware of how women were put there to avoid spending money on them or giving them a place in society; how she saw the regulations of such places as giving an opportunity for petty and general tyranny. What interested me was how both the panelists and people in the audience were determined to show Radcliffe liked solitude as a place for women to find freedom. Someone in the audience suggested that the Radcliffe heroine reconstituted an essential self after trauma. I think this is a central project for Radcliffe in all of her writing. There was an insistence from someone that Radcliffe was anti-French, & I countered that with how she created a foremother poet for herself in her portrait of Marie de France in Gaston de Blondeville. It was heartening to see how many people were there, and about 1/4 were men.

By Friday my friend, Jill had arrived, & I chose 3 sessions, where she had read some of the works and could enter into and enjoy the papers. In the days she and I were on Austen-l together, when we read Austen’s contemporaries, we read women writers beyond Austen: Burney, Wollstonecraft, Inchbald. “Historicizing Jane Austen was the first, and although it began at 8:00, and was in a fairly large room, since it had 3 “stars” on the panel and was the only session about this super-popular author, it was overloaded with people. Jill sat on the floor in a nook in the back, & I grabbed an empty chair along the end of the 2nd row.

The session was chaired by Jocelyn Harris and seemed to have been conceived by her as a kind of support for her approach in her two books by Austen: in both she reads Austen through the lens of works she argues Austen alludes to, rewrites, or whose attitudes Austen is said to have had closely in mind, agreed with.

First up was Deirdre Lynch (she of Janeites). Prof Lynch began with the recent sequels to Austen which put zombies and vampires in Austenland; the ads for these show that common readers today assume Austen’s world is an ultrapeaceful one. Prof Lynch thinks this misapprehension comes from the ahistorical way the novels are read. She suggested that Austen (like Scott) is part of a perspective on life which finds progressive modernity to be an amelioration of brutality (in the Loiterers the idea Ajax is admirable because he is superstrong and throws stones very far is mocked); nonetheless, we see that in Austen’s novels many men live on professions dependent on violence. Austen is aware of how important bodies are: we see this in an argument between Darcy and Bingley. She also sees her world is one of pressures on people which lead to loss.

Peter Sabor (very important editor of Burney as well as Austen) showed by not historicizing Austen, by reading her books as flatly universal leads to us losing a lot of their satire and social meaning. While he first expressed admiration for Tony Tanner’s work, he used this material as an example of de-historicizing reading. Tanner’s edition of P&P had 4 notes. He then close read the details in a couple of John Thorpe’s egregious bullying and boasting speeches in NA to show how the novel means to appeal to readers in the 1790s. We are expected to pick up that Thorpe’s younger brother went to the Merchant Taylor’s school (thus situating the Thorpes as very much fringe people), that Thorpe has paid a large price for his gig, and so on. In these passages, Prof Sabor seemed to read Catherine as centrally a befuddled comic figure who we laugh at because she does not see through Thorpe. I disagree with this, and it’s interesting that this reading of his is not one that can come from historizing.

Janine Barchas’s talk was based on an article she had recently had published. She took a map of the Bath area and found that near the mileage Austen says that Thorpe drove Catherine on the way to Baise Castle is what is today a heritage site: Farleigh Hungerford Castle. By assuming that Austen meant us to know this, and meant us to remember many details about this castle known at the time through rumor and tourism, Barchas was able to inject into Northanger Abbey the violence of the 14th century, a family history filled with cruelty, murder, ruins, moats, and ghosts and buried spouses.

Farleigh Hungerford, the castle gate today

Farleigh Hungerford, modern photo of castle crypt

The example became what Austen expected us to remember when Henry chided Catherine for imagining terrific happenings around her. Barchas said that we know Austen owned a guidebook which had a picture of Hungerford chapel; Austen also owned and left marginalia on a copy of Richard Warner’s Excursions from Bath (1801). While the slides were picturesque, and the history of this place as a tourist site as well as originally was of real interest, it seemed to me Barchas’s talk showed us the dangers of over-historicizing.

The discussion afterwards included lots of comments, some insightful as well as far from simply accepting what was said. I couldn’t begin to get down all that was said. Here’s just a sample: one man agreed that topicality was fun and there was pleasure in recognizing anachronisms as well as analogous situations today, but these did not account for what makes us read Austen and why she continues to be loved by those who can understand her accurately. I suggested it is not so that de-historicizing is the modern trend: all the handbooks, encyclopedias, and many editions (specifically the admirable thoroughly annotated P&P) are sold on the basis of providing historical background and explanations, and the kind of analysis that used to characterize Shakespeare criticism where we were to delight that such-and-such a character stood for some real person in the early 16th century can take readers away from the text, not into it. Someone offered the idea that because there is so much rooted history in Austen, and she has universal reach, we can adapt her freely into movies and books, like, say Bridget Jones’s Diary. There was then a comment that the modern adaptations which turn her into chick-lit reverse her deeper ethical thrust to make women more independent and show them as thoughtful and capable. And so it went.

Jill and I got together as everyone began to leave. She seemed to have enjoyed herself very much, talked about what we had heard and liked the idea of going next to “The Performing Self:—II” (Fri, 9:45-11:15 am). This panel was on actresses’ memoirs & included four papers. The first was on linen and clothing in women’s novels and the speaker thought that attitudes of heroines in 18th through 19th century novels could be plotted to show an increasing prudery. The second by Julia Fawcett was on Charlotte Charke’s memoir which Ms Fawcett saw an early example of the celebrity text meant to make someone famous and make money. Charke, the apparently lesbian daughter of Colley Cibber (whom he threw out), was an exhibitionist, & Fawcett saw her as over-performing in order to escape gender stereotypes. Mrs Fawcett made a great deal of who a memoirist alluded to, e.g., George Anne Bellamy alludes emphatically to Tristram Shandy as a predecessor text, which allowed her to show her inner subjective life off.

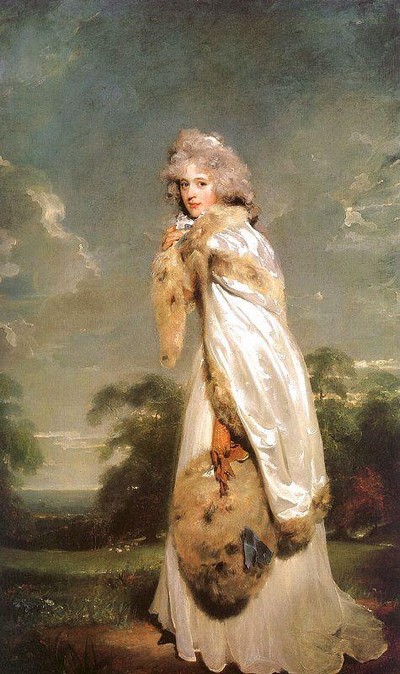

Nora Nachumi’s excellently informative paper was a cut-down version of a review she had published in an 18th century periodical of Chatto & Pickering’s recent multi-volume edition of hitherto rare memoirs by & writings about 18th century actresses. Basically she provided little resumes of the lives of the actresses included in the edition: Mary Robinson by her daughter (she died in said daughter’s arms); Sophia Baddeley by Elizabeth Steele (they were lovers, and Baddeley liked both men and women); Sarah Siddons by Thomas Campbell (he treated her with enormous respect, she is absolutely pious, everything troubling glided over); Dora Jordan by James Boaden (a life and times of the playhouse world); Mary Well’s autobiography, Ann Catley by Miss Ambrose (“hilarious”); Elizabeth Farren (married to the Duke, her life became a kind of paradise, she is central character in Emma Donoghue’s historical novel, Life Mask):

Elizabeth Farren by Thomas Lawrence, painted 1790;

George Anne Bellamy probably originally by herself (filled with intriguing anecdotes); and Mrs Billington, ditto. Nora discussed the tone and quality of the texts too (all highly subjective), and critiqued or approved of decisions the publisher had made. As I’ve read before, Nora declared that despite the glamor and interest of such a life, most actresses in the era died in impoverished circumstances; they needed luck (as when Walpole gave one actress a place to live on his property rent free); Siddons was rare to die respectable, solvent and remembered at all.

As I wrote in my first blog on the conference, I was excited to learn that a 2 volume inferior abridgement of Bellamy’s autobiography (probably polished and corrected by a male friend) was published instead of her 5 or 6 volume work, and thought about returning to my etext edition. Now I know from another friend, Vic, that this book exists online in a google book and have to reconceive my project, but it is still worthy because Nora reported the 2 volume version is inferior. The originals of all the texts are in Chawton house nowadays; perhaps the text owned at Chawton was the incompetent 2 volume one.

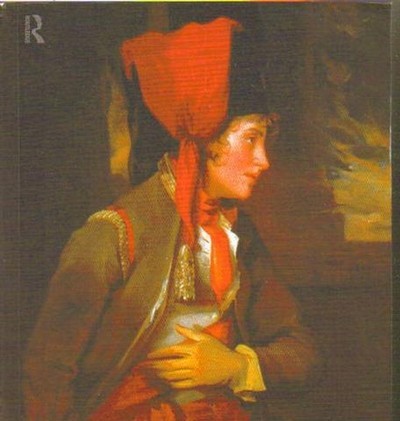

I have heard Helen Brooks give papers before, and this was as insightful and stimulating as the previous. As she has done before, she argued that her two subjects, in this case Dora Jordan and Sarah Siddons, performed roles in public which attempted to recuperate their reputation in private and so both control and develop their career successfully at the same time as they chose roles to play which reinforce the image they wanted the public to have of them. She argued that the kinds of identities women were allowed prevented them from openly wanting a career and pursuing one successfully. A respectable woman was supposed to be sincere, truthful, modest and real (trustworthy, not someone who would go off when you weren’t looking and have sex). What they did was take on roles in plays which they presented as authentic, as part of their real character so therefore they could not be accused of insincerity, hypocrisy, or manipulation; these roles were admirable ones too. Siddons was the great tragic spirit, solemn, serious, grave, & a devoted loving mother (she used one of her sons in some performances), & she played this kind of person in public off the stage.

Sarah Siddons by Thomas Gainsborough, painted 1785

Jordan presented herself as a spirit bubbling over with a joie de vivre and laughter; descriptions of her performance stress how real her giggling was.

!

Dora Jordan as Rosalind, by John Hoppner, painted 1791?

As in Ms Brooks’ previous papers where I heard her argue the same sorts of things for these and other actresses, I am not sure that these women had such conscious control over themselves. While this may be true of modern successful academics & middle to upper middle class professional people, it seems to me Ms Brooks overstresses the performed careerism of these 18th century actresses’ identities. I agree they chose roles which fit a persona that would make the public like them. During the discussion afterwards, I suggested that Emma Thompson has today followed a similar strategy in her choice of roles. In her authorized biography, Chris Nickson’s Emma: The Many Faces of Emma Thompson, we are told she is aware that playing women characters who are refined & sensitive, moral & controlled, upper class, readers, kind, modest, & gracious & deep feeling (especially in costume dramas) reinforces misleading ideas about typical English women’s identities which Anglophilic Americans have, & that Americans may think she is in personality like her characters on screen. She denies this. But this kind of naive misunderstanding helps account for her success in the US. In the UK she is nowhere as respected, and has to work to prevent her private life from becoming the stuff of (what would be to her) distressing gossip.

I also went to sessions on women’s issues and themes. On Thursday, after the first session of the conference on films, & lunch with Jim (soup) in the hotel’s overpriced dining room, I went to a session called “Aborted Courtship & Marriage: Representations of Failed Matches in the 18th Century (Thurs, 2:30 – 4:00 pm) and heard a paper by Mary Trouille on a wedding match “made in hell” and a lawyer’s contradictory views on failed marriages. I am going to review for the Intelligencer Mary Trouille’s important book, Wife-Abuse in Eighteenth-century France (a Voltaire foundation society publication) and had heard two excellent papers by her in previous ISECS and ASECS conferences, which provided matter for other chapters. This one centered on Nicolas-Francois Bellart, a deeply reactionary man who fought against divorce no matter what, but in one particular case where he was paid to support the woman, argued she ought to have a divorce because had she filed before the laws were changed again, she would have gotten one.

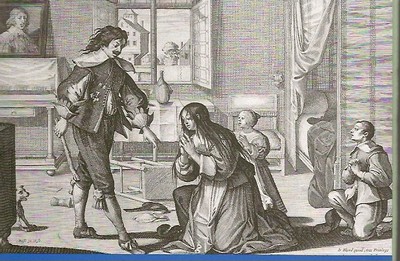

Chastisement in 18th century French illustration

Prof Trouille first gave us a brief history of the revolution and repeal of divorce laws: 1792, France legalized divorce: one could end a marriage by mutual consent; it did not require the spouses to reveal details nor assign blame. One of cited reasons could be incompatibility; women were for a brief time able to escape from violent husbands. 1803 there was a partial repeal: it was a reassertion of male authority, & presented as a restoration of the dignity of marriage and stability. Again a man had to be very cruel and harsh before the wife could complain; again adultery by the husband was cause for divorce only if he did it in the home. 1816 saw a total repeal of 1792. Bellart’s judicial memoir on behalf of divorce in the case he was hired for conceded in a tiny number of cases incompatibility was a sufficient reason for divorce; he was glib about violence & wrote of the importance of forgiveness in relationships, and he said that the 1792 law had led to a revolt of women against their husbands. I could not take down the details of the specific case, only the principles this lawyer defended. These are valuable because they reveal that even in this harsh male there was recognition of individual sacrifice & how the social order was deeply threatened by divorce. We see the wife in the case tried to bring up her unwillingness to have sex with the husband; instead she was told to exaggerate the husband’s violence. We also see how what emerges in courtrooms are distortions, approximations of what happened shaped by what one could get a divorce for.

A paper by Jarrod Hurlbert on Eliza Haywood’s The History of Betsy Thoughtless provided a complement to Prof Trouille’s case. Here we see a heroine pushed into a bad marriage by false friends and stupid relatives; she is not given time to reflect or build a serious relationship with anyone, instead put into a social world where all the pressure is for marriage which will provide monetary gain for (in this case) brothers. Lady Loveitt is the one friend she has who attempts to help her, but too late. Near the end of the novel she is to learn to live a compromised thwarted life; a reversal occurs where the husband dies and she gets to married the good man she loves, Mr Trueworth, but everything before this is exposure of how a woman needs protection from her family.

The last session I was able to get to on women writers or their themes was the third Jill and I went to together on Friday: “Competing Models of Education for and by Women of the Late Eighteenth Century”—II (11:30 am to 1:00 pm). It had two wonderful papers, one on Jane Austen, and one on Mary Wollstonecraft, and a rather poor one on Anna Barbauld. Jill & I missed the opening of Sarah Peterson Pillock’s “Mansfield Park and the Useful Child,” but we came in time to understand Ms Pillock’s original humane approach: the Bertrams teach and shelter Fanny because she is conveniently useful to them. Ms Pillock showed that Austen revealed how such criteria is a cover for exploitation and abuse. At the same time Fanny finds solace & self-esteem in the measure of usefulness to others she feels she performs. We see a child’s ultimate victory at the close of the book, at the same time as Fanny is coopted into the family & larger hard social system. So the book can function as comfort & grim accuracy.

The paper on Anna Barbauld turned Barbauld back into a pious somewhat dense propaganda on behalf of education conceived as teaching children how to fit in and worship God (and the presentation of God was the equivalent of repeating a word, or sound). Much of it was taken from a couple of her hymns to children and consisted of repetitious remarks (supposed close reading) of a few lines. Hopeless & dismaying about what such a paper says about the zeitgeist of the early 21st century. In my blog on the East Central meeting I reported how someone talked about how appealing is Lovelace in Clarissa and his potential for change shows us how we really are to sympathize with him (!); on the BSECS I reported how conservative was the politics of most of the presenters (papers on Richardson’s Grandison which take his literal presentation of religion seriously), and how the word “feminist” was bandied about as about some silly group of people, and no one contradicted that; and in my first blog on this ASECS how another graduate student wrote a paper on Austen’s Sense and Sensibility whose argument is we should pity poor Willoughby. See my comment on this blog for an attempt to do minimum justice on Barbauld’s writing and educational career.

So much of enlightenment literature is about education, from Austen’s novels to Mary Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Women.

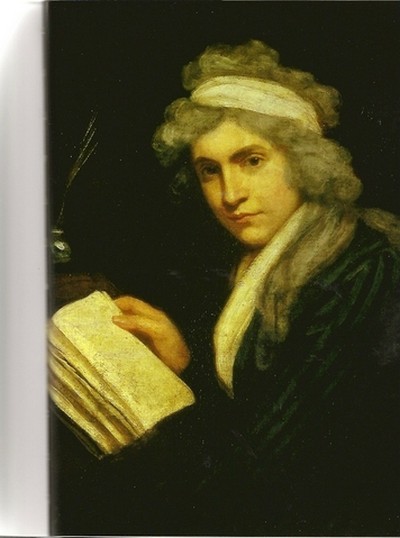

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie, painted 1797

This gets me to the third talk which Jill and I agreed was superb. Fiore Sireci described Wollstonecraft’s essay: more than one-half is an analysis of educational treatises to show how women are miseducated. Paine’s Rights of Man are directed to the common man and he outlines rights based on humanity. Wollstonecraft understands she must first appeal to those who get to set the terms and understanding underlining women’s existence; you cannot present to them their rights for they are not in a position to want these even having been so miseducated, so misshapen by their general culture. Wollstonecraft sees what Barbauld sees here too. Prof Sireci showed how Wollstonecraft challenged John Gregory by startling her reader when she described this super-respectable treatise about women as fundamentally having a salacious attitude towards them as a subspecies. Like Barbauld (see her “letter on a water-place”), Wollstonecraft resisted commercialism. Learning was for more than training for remunerative employment. Prof Sireci finally showed how Wollstonecraft addresses both men and women, & is careful to distinguish between good or well-meaning men and women educators and faulty (not thought-through) texts.

That was all I got to on women writers & women’s issues :(. There were a few other sessions and scattered papers I would have profited from or enjoyed. I especially regretted very much missing a paper on the poet Ann Yearsley (a rural yet sublime working class poet of meditative landscapes), and a whole session on Burney. In “Dialogue” (Sat, 9:45-11:15 am), there were apparently excellent papers, one of which was by Margaret Anne Doody on rejection and transport of shame, with good talk afterwards.

Sylvestre Le Tousel as Fanny, now a renter and chuser of books, bringing her treasures home to her Portsmouth home, to share them with Susan, her sister

**********

I must stopped here to watch an opera on PBS with the Admiral: Lucia di Lammermoor, another of these works where we see a woman crushed by her brother (reminding me of Clarissa): here his chief rival is her lover and the center of the opera seems to be their hatred for one another. I’ll be doing a third and last blog about this ASECS this Sunday.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Thank you for writing up these sessions, Ellen – it sounds very rewarding and as if a lot was packed in. I’m glad you and Jill managed to take part in so much of it.

I’m particularly intrigued by your account of Deirdre Lynch’s comments on Austen and how the vampire sequels etc rely on misapprehension – from what I saw of Lost in Austen, I thought there was possibly the same kind of misapprehension going on there, assuming that life was peaceful then compared to now.

— Judy Apr 16, 5:01am # - In her sixties (“Middle age”) Barbauld became involved in publishing essays for periodicals, one of which was started by her brother. During this period after herself having run a successful respected dissenting school for 11 years, and worked as a tutor for girls on and off for several more, she wrote two remarkable essays, one on Education and the other on Prejudice for the Monthly.

For the essay on Education she is responding to Rousseau’s Emile and Genlis’s Theodore and Adele: her idea is the notion that education can be controlled by a teacher and successful if the child is removed from society and then manipulated (for that’s what it is) is absurd: you cannot remove the child from society; what you can offer in a classroom is instructive; the education of a child is a holistic experience that is going on since his or her birth, and central to what the child becomes is his or her social and economic circumstances, what the parent do and how they behave. It’s an existentialist approach which shows the messy ambiguous particular worlds the child lives in (including with peers) makes him or her into the person he or she becomes, as much as innate nature. She is calling into question the Enlightenment notion you can change a person through reform movements in school or particular methods. I do love how she disapproves of teaching children falsehoods to get them to believe and do what you want, and saying to oneself that later they’ll be glad you did so. Later they’ll have imbibed incultured hypocrisies and acceptance of cruelties this way and do likewise to their children themselves.

In “On Prejudice,” she shows we cannot live without it, that knowledge is grounded in someone’s direct conscious experience and there must be faith in authorities as the child grows up, for he or she builds on what he or she is given instructionally and reacts to experience. All learning is situated (once again). You can try to teach principles of ethics, but they will only “take” if they direct your actual behavior. When the child grows older, he or she will insensibly begin to think or react or feel on his or her own.

My feeling or problem with the latter is only that she is too general or avoids the hard realities as she did in her “Against Inconsistency in Expectations.” It’s fine to say accept what you are and your choices, but it’s not easy to do, and choices have been limited from the start. To me she avoids the pain of educating a child for I have seen how a child’s nature can be cruel, dense, difficult, a bully, and determined to imitate the generality of what she (or he) saw around him, using lies when I didn’t try to elicit information, just because, more than defensively, and I made every attempt in Barbauld’s way to at least counter these impulses somehow and failed utterly. Why? Because this was part of the child’s nature and encouraged by the society I find myself in. I guess I’m saying Barbauld isn’t pessmistic enough and prefer Austen’s brief succinct words given Elizabeth that that which counts most can’t be taught. And what bothers me about say Rousseau’s and Genlis’s methods is they enact deceit themselves, manipulation.

E.M.

— Elinor Apr 17, 10:13am # - Terribly interesting, what Peter Sabor says about not historicizing Austen, and reading her as flatly universal – clearly knowing details (Merchant Taylor’s, etc.) does enhance; but then it seems contradictory that Sabor’s own take on Catherine as a befuddled figure does not come from historicizing. Can you explain this? And why you disagree with him? Hilarious, your pointing out that Barchas’s article shows the dangers of over-historicizing – I was thinking that as I was reading your description! Brilliant description of the talks, very enjoyable, thank you very much!

— Diana Apr 18, 7:49am # - Dear Diana and Judy,

Like elsewhere, there are fashions in scholarship: historicizing is -- and going anti- the once upon a time new close reading and textual criticism (found first in I. A. Richards, then The Well-Wrought Urn), and performed so brilliantly by Tony Tanner that, as Prof Sabor admits, the most recent Penguins reprint his essays as appendices in Jane Austen editions. Similarly, the idea of life as performance and not just in women’s autobiography. I feel this comes from the overt careerism of papers nowadays, a bye-blow of seeing literary works in the context of sociological real-world networking and the marketplace.

I agree that Lost in Austen is based centrally on the idea that Austen’s time and places were places of quiet peaceful escape, and if it’s not true, the opening sequence of that film which contrasts the hectic, harried, anonymous, noisy, abrasive public life of London with all that is opposite of this inside an Austen book was strongly appealing.

— Elinor Apr 19, 12:35am # - Journalizing, 4/19/09. My computer working right again, I added pictures of the seige of Mainz (described by Radcliffe in her travel book), Farleigh Hungerford Castle (claimed to be in Austen’s mind for NA by one speaker), of Elizabeth Farren, Dora Jordan, and Sarah Siddons (for memoirs of actresses), John Opie of Mary Wollstonecraft (educational writings), and one I'm very fond of, Sylvestre Le Tousel as Fanny Price bringing her precious bundle of books home to share with Susan.

I also looked for other links, one I didn’t put in as I don’t know how to convert huge URLs into tiny ones, is to an essay on Radcliffe as picturesque. Very good. I love the picturesque and think her power for me comes from the pictures in her books, the visiosn (Beatrice Battaglia agrees). It comes with interesting illustrations and available to the public. It’s called "The English Landscape Garden and the Romantic-Era Novel Changing Concepts of Space" by Marie-Luise Egbert (so you can google for it that way).

Or go to:

http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/encap/journals/romtext/images/articles/cc05_01c.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/encap/journals/romtext/articles/cc05_n01.html&usg=__XpEic-7s9uDfGipvoo_UVDWBLaU=&h=414&w=600&sz=121&hl=en&start=10&sig2=Cu8N8JATA4KHaB1WWLntgw&tbnid=e822igAE5O0orM:&tbnh=93&tbnw=135&

prev=/images%3Fq%3Dradcliffe%

2Bgothicism%26gbv%3D2%26hl%3Den%26client%3Dfirefox-a%26rls%3Dorg.mozilla:en-US:official%26sa%3DG&ei=HpLoSbXCNI_vnQeSwqzvBg

— Elinor Apr 19, 8:39am #

commenting closed for this article