Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Victorians Reassess Victorian Keywords at the MLA · 10 January 07

Dear Harriet,

I managed to go to 3 Victorian sessions at the MLA where the goal was to rethink the meaning of keywords (and ideas) central to Victorian studies since they were used by Walter Houghton in his Victorian Frame of Mind and Raymond Williams in his books, particularly Keywords. In each session there were 3 papers where 3 linked words were reassessed.

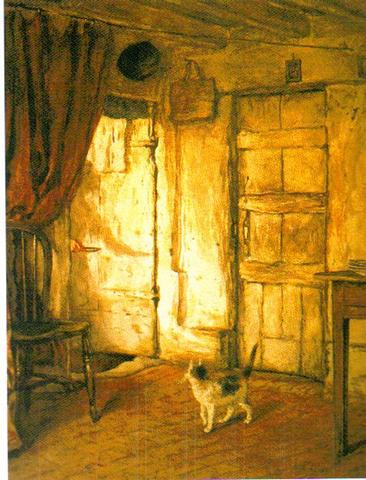

Unfortunately as far as I could see, there were no sessions on Victorian visual arts nor theatre nor music. Nonetheless, I’ll include 4 characteristic Victorian paintings here (the 1st I’m particularly fond of).

In the first session, the words were "psyche," "aesthetics" and taste." Jill Matus looked at what Victorians meant by the idea of the mind, how the mind connected to or interacted with the body, and both to the world of the spirit and art. She was interested, she said, especially in the "vexed concept" of "trauma." Why did the word "emotion" begin to replace more nuanced words like passion and affection. Victorian people puzzled over sleep, sleep walking and the unconscious as an agent. Antonia Losano talked about how aesthetics (ideas about beauty) came to be divorced from norms of social and political life. This was turning away from Ruskin’s point of view; she cited Williams as saying Victorians valued objects in themselves, as forms apart from interpretation and practical considerations; she described a number of novels where the characters practice artistry and judge the success of a work by its fidelity to nature (thus art must include the unpleasant). She called this materialistic. Anthony Harrison asked what constituted good taste for different Victorians. His paper was about how Arnold’s poetry was rarely valued by readers while Alexander Smith’s was lavishly overpraised. He saw this as a gulf between high culture (upper class taste) and enjoyment of sensation and what’s obvious (the more popular, less educated, less refined, lower class taste). He defined taste as aesthetic desire, an "expression of yearning for self-completion in a non-human material other," and from this definition argued there’s no taste outside ideological categories.

The talk afterwards included the question, why not say some kinds of desires are better than others, and assertions that 1) we cannot separate taste from morality, and 2) in practice we must satisfy ourselves as a community by continual conversation (exchange of views) rather than consensus.

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836-1893) Autumn Evening (1883)

In the second session, "secularization," "hypocrisy," and "slavery"

were explored. Charles LaPorte wanted to counter the tendency of scholars of the 20th century to emphasize secularization during the 19th century, and show how important religion remained. He analyzed Elizabeth Browning’s Aurora Leigh as religiously motivated poetry. He suggested seeing the downplaying of religiosity in Victorian studies until recently can help account for the marginalization of women’s poetry.

Suzanne Daly described how Houghton discerned 3 kinds of social and religious hypocrisy among Victorians: they sacrificed sincerity for propriety; they pretended to be better than they were; they refused to look at some deeply unpleasant and unidealistic aspects of daily life candidly. They thus reinforced social conformity, moral pretension, and evasion. Prof Daly then went on to argue post-colonialist Victorian studies display new hypocrisies: books are written to prove the Victorians really believed what they said (were not hypocrites), and whatever blindness this involves it’s necessary for social interaction. Hypocrisy is made to seem morally neutral, e.g., recent apologists for neoconservatism (Gilmore, Fergusson, and Paul Johnson) attack books which show colonial rule as simply evil (e.g., E. M. Forster, Said, Paul Scott). Gilmore writes English people believed they belong to a more advanced civilization; they did not claim they would have the advantage forever. Fergusson quotes Disraeli to the effect that all organized government is a conservative hypocrisy, and defends hypocrisy. Prof Daly showed how Gilmore makes Victorians better than they were; how he and Fergusson are justifying the recent overt imperial agenda of US and UK governments; how all three evidence an imperial nostalgia. So Victorian hypocrisy is still with us, just in different realms of life.

Audrey Fish wanted to add a keyword not found in Houghton or Wililams, and still not used for organizing sections in central Victorian anthologies: slavery. She argued that the abolition of slavery as an ideal as well as strong racial discrimination was central to white British culture and identity and she analyzed some works and cultural happenings to show this, e.g., Carlyle and Mill’s debate; Jane Eyre; travel books; the popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in England.

The talk afterwards came out of objections to what had been said. One woman seemed to suggest that we don’t know as yet now to read Victorian women’s poetry and she (and others) seemed to resent the use of the word "sentimental" as descriptive of Victorian women’s poetry. A woman sitting near me objected most Victorian scholars today are practicing class and race and ethnic hypocrisy. Several people suggested (rightly in my view) many Victorians were not fervent abolitionists at all, and that the upper classes in Britain as a group tended to side with the south.

I spoke up in this session and suggested there were Victorians who strongly objected to hypocrisy in social, psychological and religious life, and Anthony Trollope was one of them. His New Zealander is a strongly worded treatise intended to show how lying destroys the social fabric of everyday life, makes trust and relationships tenuous and hollow, a mockery of religion so that it can become a cover for hatred and bigotry, prevents people from experiencing real pleasure, enjoying art, and was undermining what British civilization had achieved by substituting the factitious, inferior and false for real goods (be it unadulterated food or good art). True enough, he couldn’t get his book published (!). I also suggested much work had been done to enable us to understand & love Victorian women’s poetry, & instanced Isobel Armstrong’s wonderful essay on "gush" (a way of suddenly expressing intense emotion and unacceptable ideals breaking through repression and anguish) and Paula Backscheider’s recent book on poetry where she tries to identify genres of women’s poetry.

Helen Allingham (1848-1926) Coming Events (1886)

In the third session, the words were "work," women’s work," and "career." Martin Danahay discussed how what Victorians (and Houghton) meant by "work" differs from what people today mean by the word and concept. He quoted Carlyle for whom work meant production of things and was a kind of therapy and also a religious gospel. Critics have shown how Carlyle’s ideas assume materiality as a measure of the worth of your work. If you don’t produce something, or have something to show in return for your work, somehow you haven’t worked. Women’s housework, mothering, intangible work doesn’t count, especially if it’s not paid. Raymond Williams took a larger political perspective, connecting work to the "cash nexus" and defined kinds of work in terms of class niche, who has control over and will use the product. Williams said work is any effort you make whether you are compensated or not. Prof Danahay gave out an image of Ford Madox Brown’s famous picture of people and showed how it made visible Victorian concepts of "real work." He quoted a recent book on masculinity in the Victorian period and work (Men at Work—an art historical study). He said that for us these definitions don’t sufficiently take into account intangible products, work in say the entertainment and leisure industries, networking and funding large projects; intellectual and artistic work is devalued.

Deirdre d’Albertis gave a paper on women, writing, and work. Men’s work was alienated and women did "affective" labor (in the home). She wanted to present women writers at work which from the Victorian standpoint would be recognized as work and respected. So she discussed women driven to work by material necessity, and work which included the negative realities of routine, deadening effects, and exhaustion. Her examples were drawn from Hannah Culick, the unfortunate woman who was Arthur Mundry’s mistress and bodily servant (my view would be abject slave), and from Eliza Lynn Linton’s ideas and life where successful writing brought literary power. Prof d’Albertis emphasized how humble, arduous and vile were many of Culick’s tasks and how Culick affected to despise the women she worked for as idle and frivolous. Linton apparently rejected prototypes of womanly work; she scourged the "new woman" who wanted to be independent, individualistic, and display herself. Trollope was quoted: "work that is unbought will never help anyone." Linton’s work was bought. She was an influential journalist—or so she thought.

Molly Youngkin discussed the idea of a career. In the 16th century it meant speeding along; by the 19th century it means an individual’s progress in his or her vocation. She investigated two Victorian novelists’ attitudes towards their writing to show that one, George Moore, saw himself as following a career, and the other, Henrietta Stannard didn’t. Moore positioned his books to make them part of the canon; he made sure Esther Waters was regarded as serious fiction (socially concerned) and printed in a prestigious fine edition. Stannard who wrote woman-centered fiction about issues of concern to women too was much less aggressive when it came to trying to create a reputation for herself after her lifetime. She did not try to publish her taboo-breaking A Blameless Woman (about a woman deceived into marrying a man already married to someone else) as a significant social or sociological event in a fancy package. In her life she joined and created societies for women authors; she argued for fairer treatment of women, but she was content in her autobiography to represent herself simply as a commercial success. Stannard asked why should men object to women supporting themselves, why seek to degrade women’s achievement, and wrote that Gaskell, Eliot, and Bronte matched Dickens and Thackeray’s achievements. Prof Youngkin ended on a biography written about Stannard soon after Stannard’s death; this work presented Stannard as a popular good woman, someone who did charity work, who adopted stray cats, and the biographer never mentioned A Blameless Woman.

I don’t have any notes for talk afterwards. I said nothing at the time but did feel troubled & puzzled at admiration for Culick, an exploited and twisted personality coerced into degraded sex amid filth. Culick’s despising of the women she worked for reminds me of the remarks Barbara Ehrenreich made in her Nickel and Dimed about the middle class women she encountered who used and underpaid working women (as cleaners, nannies, people to do the unpleasant time-consuming tasks of life for little money), with the different that Ehrenreich was attacking middle class fatuousness and complacency while Culick was resenting her employers for their tasteful quiet women’s lives and norms. Why should one glory in filth and misery? What’s wrong with womanly behavior? In many circumstances it’s all that can command a minimal respect. I felt there was a preference for male norms no matter what they bring. I felt equally disturbed and wondered about the use made of Linton as an admirable exemplar of work. I’d call Linton a careerist (attracting attention to herself by condemning other women), a spiteful hypocrite, a Martha Steward in reverse. Her texts provided fodder for anti-feminists. It matters how your work-as-writing functions, what its effect on others might be.

I also wish there had been more talk about how the work some academics in universities do is privileged. We have easy hours, little supervision, and the tenured and tenure-track people very good pay and benefits. Leslie Stephens is a counter-example of a Victorian who worked hard producing no products and not a lot of money. There was an intellectual class of work in the later Victorian period, people who acquired niches in government and institutional and educational offices.

For Trollope, Harriet, work is "physic" from disquiet, disillusion, pain.

The word career could have been delved more. The word first emerges in the modern sense in the later 17th century as descriptive of a man who makes the military his career. He is a career officer. Other upper class males might serve in the military for a short while and then go on to administer their estates, go into politics or live the life of a gentleman. The French phrase, "a career open to talent" is one which recognized how few

niches and positions were open to people without connections, money, and access to people with the power to give niches away in return for some form of reciprocal payment. It was used in the 18th century, and referred to the sort of work where real talent was necessary. Thus the word would make visible the inequailities of basic relationships between families and individuals in society along with the refusal of men and powerful mixed sex groups (families, networks of people in power) to recognize women’s lifetime achievements.

Ford Madox Brown (1821-93) Work (1852-63)

I did go to the session dubbed the "interrogation" of William St Clair whose book, Reading Nation overturns many assumptions which have justified literary studies for years. While the session was apparently about the romantic period, his ground-breaking iconoclastic book is corrosive of all sorts of assumptions which have been used in Elizabeth through 20th century studies, and especially Victorian ones where the idea of particular authors or books influencing whole groups of people into social progress or keeping them back from progress has been important. Is the parliament of texts approach (intertextuality) as unreal as the parade of texts has been? If it’s true only a tiny percentage of people got to read any particular book at the time it was published, how can you say that X was responding to Y because they were published in the same year and discussed in Z’s review and A and B’s correspondence? Were people until the 20th century stuck reading obscure popular older texts, mostly trash, junk, religious conservatism which served the interests of the powerful by keeping out of the minds of the many real information about how their society was run?

Beyond the reality of what people actually got to read, we nowadays understand that different readers read utterly idiosyncratically, often misunderstanding or simply ignoring what the author’s views in the text are.

The people asked to question Professor St. Clair were respectful, and he presented his case cogently & persuasively. He said much quickly. A rare exception to the use of copyright and monopoly to keep new texts expensive, in the hands of the few and making profit for a few was Byron’s Don Juan. He said it can be shown that people did read it as very subversive. He said it can be shown that when a text that was subversive and contemporary could be gotten to large numbers of people, they went for it. Such was the first edition of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. He said most pamphlets were printed at a maximum number of 500; 5000 of Burke’s Reflections on the French Revolution were printed. He said hardly anyone ever read Mary Wollstonecraft; her views were known only through those deeply hostile to them who used her name to write vitriolic attacks on feminism. He said when a work reached the populace through the theatre, it was over transformed from a subversive to a frivolous reactionary work (he instanced Frankenstein). He said in the 19th century every monopolistic practice you can think of was adhered to, every restrictive practice in distribution; publishers prevented abridgements, did all they could to stop libraries from disseminating new books cheaply. Those who tried to break the cartels were driven out of business, given large sums to go away.

I remember much from Hardy’s Jude the Obscure but know the part that startled me most the first time was the opening where we learn that Jude can’t get any books to learn with. He can’t get Latin readers; he can’t get good novels to entertain him. He can’t learn any news but from crude newspapers which present lies. All the talk around him is religious cant.

The people from the audience who queried Prof St. Clair seemed to want to argue that this or that publication did reach a lot of people. People seem unwilling to see the discipline of English as one where we study a tiny group of elite texts whose excellence only small proportion of people have ever been able to understand and even fewer value.

George Clausen (1852-1944), A Spring Morning, Haverstock Hill (1881)

My next letter will be on the 18th century sessions I attended.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Don’t know much about the Victorian texts, but the St. Clair book looks like one I’ve got to read. I’ve been looking for a more useful, and concrete model of reception studies than we generally use in literary studies.

I never had much patience with the literature as subversion or literature as ideology models I saw practiced in grad schools in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

For one thing, the choices offered seemed so leaden, and then one still had all the work of assessing the literary value. My rule of thumb tends to be, is this a text worth rereading? If so, then we can probably make a case for its value, one way or another.

I also think that a much wider range of materials can be read as fragments, as pieces of the puzzles we construct to make sense of other, more important works. I’m a big believer in "episodes," narrative or otherwise, that I think are worth retelling in one context or another.

I did a course on "life-writing" in the late 18c, and the real shocker was placing Mary Hays alongside Elizabeth Hamilton’s Memoirs of Modern Philosophers. Hays never had a chance. What I discovered, though, was that no one could take Hays seriously after reading Hamilton. I don’t think either book would have been as effective in that course if it hadn’t been paired up with the other. Now if I could figure out how to put them side by side without Hays getting annihilated . . . .

dave

— David Mazella Jan 11, 3:07pm # - I know I highlighted subversive texts as those that are changed, and indeed St Clair thinks that texts which work to undermine an establishment are not reprinted. However, that’s only one kind of text kept out of the hands of those without money or education in the 19th century. St Clair talked about the Mudie Library system with its artificially high prices; he talked about the actual runs of more cultured books and novels (often very small in the Romantic period—Scott was an exception). In one of the many reviews of Tomalin's book on Hardy I read how when he was 12 he had such a hard time getting his hands on a Latin book. He wanted to teach himself Latin. It was priced out of his range and there was none in the local bookstore. Latin was for leisured gentlemen.

I’ve been reading life-writing by 18th century women today. They are problematic. It seems before the mid-19th century the taboo against writing about yourself and publishing it, especially for women was strong, and just about all of these life-writings are appeals, apologies, confessions, vexed, lying, uncomfortable stories of desperation. Rare exceptions include the travelbook. In fiction the Utopian or philosphical book might be comparable.

We are going to be reading Hays’s novel, Emma Courtney on my small EighteenthCentury List starting next week.

E.M.

— Elinor Jan 11, 11:26pm # - I know this will sound heretical, but I think that Wollstonecraft gets considerably worse the closer she gets to autobiography. I certainly feel that way about her fiction, though I’m willing to listen for arguments the other way. Wollstonecraft for my money is at her best pamphleteering, where her oddly impersonal tone seems most effective. But I haven’t spent much time on her travel writing.

Burney’s diaries were the real literary discovery in that course, though I had to use the Penguin selection, which is well done, but students did feel like they were being pushed this way and that by the selections. Nonetheless, Burney’s diaries seemed as strong as anything we read that term.

DM

— David Mazella Jan 11, 11:42pm # - From Kathy C:

"By the way, I loved the Autumn Evening painting, which I hadn’t seen before. Do you find these in books or online?"

In answer:

I found the Grimshaw picture online. I was alerted to it by an Alan Bennet "Untold Story" in which he describes his musings and meditations while walking in Leeds, and instances these paintings as peculiarly lovely and redolent of Leeds as well as a common imgae we have Victorian England in the autumn. Grimshaw painted autumn often.

I do love them and will put more on after we finish the month with Millais pictures on Trollope-l. I found on the Net today a small catalogue from an exhibit and did buy it and when it comes I’ll have (I hope) some real beauties to scan in.

My desktop picture is Autumn Morning, an image of a painting by Grimshaw of a mansion seen in the distance behind a stone gate in autumn The stone gate is in ruins. On the one side there is just a central frame pediment and no columns leading away from it; on the other the short columns are crumbling. You see a stone walk leading away from the platform on which the central opening of the gate rests. The trees are bare. All browns and deep rusty orange-browns, dark red and lighter red browns, haunting yellow sky; lots of fallen leaves.

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 12, 12:02pm # - From Martin Danahay:

"Thanks for the great summary of my talk I should have given out the references – the art historical study is Tim Barringer, Men at Work: Art and Labour in Vicotiran Britain (Yale UP, 2005) and the other is my own Gender at Work in Victorian Culture: Literature, Art and Masculinity (Ashgate, 2005).

Barringer and I deal with similar material from different perspectives, he from an art historical and me from a cultural studies (literary with pictures :-) perspective.

I also gave out an image of Isambard Kingdom Brunel standing in front of the chains of the Great Eastern. Martin"

— Sylvia Jan 17, 3:23pm # - From Jonathan Farina on Victoria:

"Dear Ellen,

Thank you for that: I wasn’t able to make all three sessions, so those comments were helpful … and the paintings were even better! I love Grimshaw.

Anyway, thanks again.

All best,

—Jon"

— Sylvia Jan 17, 3:25pm # - I received the following as an email letter offblog and have corrected the blog accordingly:

"Ellen,

Thanks for attending the Keywords sessions and also for your comments about how the discussions at each session might have been extended. I did want to point out two factual errors in the discussion of my session. My last name is Youngkin, not Youngren, and the author I discussed was George Moore, not Edward Moore.

Thanks again for your commentary,

Molly"

— Sylvia Jan 17, 5:15pm # - My first glance at this blog. I must say, I was astounded that so many scholars claimed that the word "work" was not used for women’s work. But it WAS. Any kind of needlework was called "work". One sees this over and over again in fiction, not to mention household and needlework manuals. A woman takes her "work" out of her pocket, she spends the morning "working," she "works" three rows of slip stitch. How can the presenters not have known that?

— Karen Lofstrom Jan 18, 10:00pm # - Thank you for your comment, Karen. Of course. Women "worked" all day. It seems to me this exemplification of work was not brought up because what was valued was what was associated with men. As I wrote in the blog, there was evidently a strong preference for male norms. Sewing is "womanly."

I’ve also been thinking of two further qualifications. First it seems an exaggeration to say Victorians didn’t recognize non-concrete work. Prof. Danahay did have a picture showing a man funding different enterprizes, but they also recognized intangible activities. I today was reading in Trollope’s The Bertrams, the following description of work:

[the uncle of one of the novel’s male protagonists] was "a director of the Bnak of England, chairman of a large insurance company, was deep in water, far gone in gas, and an illustrious potentate of railway interests. I imagine that he had neither counting house, shop, nor ware-rooms: but he was not on that account at a loss whither to direct his steps; and those who knew the city ways knew very well where to meet Mr George Bertram senior between the hours of eleven and five. (Ch 5, "The Choice of a Profession," p. 55)

On careers too, Frances Hodgson Burnett, part American, but born in the UK with many of her stories set in the UK, and living there on and off for decades, had a high ideal of her calling and threw herself deeply into her books. That’s why they transcended the commercial nexus she exploited consciously.

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 19, 1:41pm #

commenting closed for this article