Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Women in the long 18th Century at the MLA · 12 January 07

Dear Harriet,

As I am too tired to read and it’s too early to go to sleep, let me tell you about the sessions and papers about the long 18th century I attended at the recent MLA meeting.

Although there was a session on the visual arts in the 18th century I didn’t get to it, and again just send along with my letter some appropriate (I hope) and favorite images, as this first:

Francoise Duparc (1726-78) Woman Knitting (n.d.)

One of the first panels of the conference, "The Politics of Engagement: Reconsidering Women Writers in Time of War" (No 18, Wednesday, 5:15-6:30 pm) presented 3 papers on women writers during war. Two used Virginia Woolf’s anti-war treatise, Three Guineas centrally; the first of these, by Erin A. Murphy, "Silent Histories" linked the later 17th century feminist intellectual writer, Mary Astell, to Woolf’s famous essay. After the civil war Astell called for a wman’s educational retirement; Woolf wrote that education is an innate human desire but nonetheless how people (women and men) have ever worked to prevent funding of, to mock, and generally thwart women from becoming highly educated. Both these women writers were born to the privileged classes of their era. Astell writes to prepare her readers for more women writers; Woolf tries to account for women’s support of war. Woolf says women get out of the house and achieve individual freedom and usefulness during wars. She valorizes the writer who successful present themselves as someone to take seriously; thus Margaret Cavendish is a nonsensical eccentric while Aphra Behn an empowering model.

Like the third paper, Rachel Hollander’s was about another era than the 17th to 18th century, but she did argue that in Woolf’s Three Guineas Woolf says the way people can prevent war is follow an ethics of indifference: they must remain at a distance. We need not to identify with one side or the other, not to reward people for killing ever; women should form communities outside the structures males provide; they must counter the male instinct for fighting. Prof Hollander pointed out that car stickers which say "support our troops" reject an ethic of indifference slyly.

Lauren Goodland was the respondent. She talked about the impasse that would result from following Woolf’s ideal. You can only fight injustice if you have power to. In Astell we see the passion of ambition. She argued (as she did in the Trollope conference this summer) that liberal democratic thought prevents people from preventing others from doing harm. You must do what’s necessay to seek enough power in the political arena of law and custom to stop war. She seemed to justify Hillary Clinton’s compromises.

I asked Prof Hollander what she thought of Q. D. Leavis’s vehement viotriolic attack on Woolf’s Three Guineas. From her analysis, it seemed to me that beyond Leavis’s intense resentment of Woolf’s elite upbringing and connections, and dislike of feminism as threatening Leavis’s acceptance by men, Leavis may have found repugnant an ethics of indifference in a war against a man determined to exterminate whole peoples, a hideous monster of cruelty and bigotry. It’s one thing to advocate say we insofar as we can as citizens enact an ethics of indifference towards the Arab world’s cultures when a sadistic mindless bully like the present President Bush wants to create mass slaughter to no purpose; it’s another to turn your back on a Hitler trying to become a tyrannical bloodthirsty fascist dictator over all Europe. Alas, Prof Hollander had not read Leavis’s infamous review.

Jim and I met for dinner and then I went to a second panel that night on eighteenth-century women, "Advocacy for Women in Pre-Enlightenment Thought" (No. 93, 8:45-10:00 pm). Shannon Miller gave a paper on the eloquent poetry of late 17th century poet, Mary Chudleigh, showing how Chudleigh used Milton to carve out a realm of freedom, self-respect, and learning for women. Sally O’Driscoll talked about laboring women who wrote ballads, and covered (briefly) medieval troubadours, and (more at length) 17th and 18th century ballad-makers who celebrate sexual appetite. Rivka Swenson analyzed the prologues of the early 18th century playwright, Susannah Centlivre to show how they enact masculine values, are transsexual (in effect). It seemed to me (though this was not Swenson’s point) that Centlivre was following in the iconoclastic and ironic undercutting traditions of Dryden and Behn.

What interested me here was how all these women poets turned to famous male poets in order to present a female or original point of view. I spoke up to tell of how this fall I had been reading Lucy Hutchinson’s deeply moving eloquent elegies mourning the death of her husband and been surprized to discover how often she paraphrases, imitates, elaborates intensely erotic metaphysical conceits drawn from Donne and Henry King; for example, the opening of the first:

Leaue of yee pittying freinds; leaue of in vaine

Doe you perswade the dead to liue againe

In uaine to me yr comforts are applied

For, ‘twas not he; twas only I That died

In That Cold Graue which his deare reliques keepes

My light is quite extinct where he but sleepes

My substance into the darke vault was laide

And now I am my owne pale Empty Shade ..

She does not turn to religious imagery of the type found in Herbert. In her close translation of Lucretius she uses 17th century scientific language to present atheistic ideas. In these elegies she doubts God’s justice and even his presence.

Lucy Hutchinson (1621-81) by Peter Walker

I was eager to go to "British Women Writers and Readers, 1760-1810" (Thursday, 1:45-3:00 pm, No. 222) and the papers were all excellent. Scott Krawczyk’s paper, "Reading Barbauld’s Readers" was a delight. He demonstrated how her years as a teacher and genuine respect for her readers led her to create good editions of earlier texts for the public. Barbauld emerged as an open-minded liberal presence in her era who brought good texts to others and helped create perspectives drawn from the powerless and woman’s experience. He described editions of The Spectator, Tatler and other periodicals where the opening volume of 3 contains many issues form the earliest years of the periodicals, & the last 2 squeeze in haphazardly the rest; editions where there are no notes, no attempt to project a point of view. By contrast Barbauld chose her texts carefully, planned ahead, edited and shaped her texts with an idea to making them understood by her readership. He suggested her original transformation of the age-old parable of the town and country mouse in "The Mouse’s Petition" influenced Burns’s "To a Mousie." The lake poets (more gentry people) were hostile to her. Coleridge, Lamb and Southey routinely dismissed her; Southey was particularly scornful, and insinuated humiliating insults (as when he called her naked); they derided her excellent "On the Origin and Progress of Novel-Writing" as ignorant & preposterous when it’s the first history well before Margaret Doody to show how inadequate is Ian Watt’s terrain: he omits the women writers of the later 17th through 18th century. Barbauld begins with Sidney’s Arcadia, and understands the breadth and flexibility of romance.

Patricia Comitini’s "The Addicted Reader, and Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey set me thinking afterwards. Her demonstration had been (in effect) the familiar one about how Austen wanted to show the real terrors of life lie in ordinary reality and not the transcendent texts Catherine becomes addicted to. I felt later on that her opposition between the terrors of romance novels and terrors of life left out the presence and significance of history in the novel. Eleanor Tilney thinks Catherine is referring to recent (1780) street riots when Catherine alludes to a new gothic novel guaranteed to terrorize you; they begin to talk of history; when Henry realizes Catherine thinks his father may have murdered his mother, he refers to the possibility of such crimes occurring in remote parts of Europe or places in the British Isles beyond Southern England. This continually self-consciousness, reflexive and literary book bring together the origin of terror (at any moment in time all may change), a genuinely uhappy and real death (Mrs Tilney died years before her body went), real misery (such as Henry’s mother knew).

Caroline Breashears gave another paper on women’s memoirs, this time about the paratexts that frame them. She asked what is the presumed relationship between an author and her readers: is the author warning the reader, appealing for money, help in suing, a renewal of her respectability? Gerard Genette suggested paratexts (title pages, acknowledgements, prefaces, afterwards) provide zones where the writer can directly transact with the reader. Prof. Breashears wanted to show us how in these paratexts women writers try to distinguish memoirs which are intended to be read as books by respectable women appealing for help, confessing, making visible unconventional lives from "scandal" or "whore’s" memoirs. The features to look for include: a conversational tone; inserted letters and poems to the reader; an absence of titillating descriptions. In her Memoirs about her wretched coerced marriage, Catherine Jemmat tells of how her husband transgressed the bounds of humanity; in her Apology, George Anne Bellamy inserts letters to a friend, provides a nuanced sense of intimacy, seeks sympathy.

Laura Runge described commonplace books by two women. Mary Capel, the wife of an admiral of the blue, compiled a miscellany by others as well as herself; she included poetry about political affairs, showed personal interest in other people and treated them as if they were as great a poet as Pope and other famous authors of the era. She revelled in creating a book. Eliza Marryat’s manuscript is an imitation of print artefacts. She copies out 28 of her own poems (19 are in a single hand), and mirrors the world of gentry of which she imagines herself a member. She belongs to the world Vickery described in The Gentleman’s Daughter. Marryat unashamedly prefers local poets to the famous, and reads in an idiosyncratic way. Her choices of poems from the well-known suggests she was at heart a sombre religious individual.

Prof Lunge’s description of the coteries and milieus which gave rise to both these books reminded me of the coteries I found in manuscripts when I was finding unpublished poems by Anne Finch not yet attributed to her. I also saw how such groups are erased from printed books where the editor or publisher compiles what he or she can find according to his or her taste. For example, one of the most marvelous compilations in print of the early 18th century, the 1724 Hive, an astonishingly good volume; its quality reminds me of the sixteenth-century collection England’s Helicon; it represents the best and most beautiful songs of the preceding generation. It includes no less than 16 poems which are clearly by Finch. However, these poems seem to have been gathered from many manuscripts and there seems to be no close connection between the named authors necessarily or sets of poems.

By contrast, British Library MS Harleian 7316 includes references to many members of Finch’s circle: Kitty and Nan, the "sisters" who sing and play the lyre are Catherine and Ann Fleming; "lovely Fanny," "Lord Digby’s daughter," Lady Frances Digby Scudamore, mentioned in two of Ann’s poems (which include references to the Flemings) and in Gay’s poem to Pope upon his finishing his Iliad, which couples Anne with Scudamore ("See the decent Scudamore advance,/With Winchilsea, still mediating song"). There is a lovely "Lady Betty" whose dimples suggest a child (Lady Hertford’s little daughter?); the group is pictured at Sutton, a seat and park nearby Coleshill, in Warwickshire, the home of Lord Robert Digby, Lady Scudamore’s cousin, to whose house we know from Finch’s other ballads Catherine Fleming had gone in 1718). Finch’s love of music comes through; Finch is bidding a gay farewell to the Digby circle, using the latest trend: Scots dialect.

Jean-Francois de Troy (1679-1752) The Reading from Moliere (1750?)

"Re-engendering Reason," was a panel (No. 507) held late Friday afternoon and arranged by the 18th Century French Literature Division. The three papers were on later 18th century French women writers. Jennifer Lou Gardener talked about narrative strategies of French women novelists. In the later 17th to 18th century many many women published in the literary marketplace romanesque love adventures, fairy tales, philosophical fables, subversive dissenting stories. Mme (Claudine Alexandrine Guerin) de Tencin was typical in how she unobtrusively displayed and critiqued the value systems of the era, showed women punished for excessive desire and yet offered a wish-fulfillment fantasy. We see how maxims are used to manipulate women. Prof Gardener’s description of Tencin’s tone and procedure made her sound like Jane Austen; the method of the plot-designs anticipates Fanny Burney. Zeina K. Hakim gave a paper on Isabelle de Charriere where she showed how Charriere refused to allow her heroines to become hysterical in the most trying situations; Charriere’s heroines exert self-control while they are deprived of their innermost desires.

Both speakers seemed to feel that the 17th century French male models suffocated what women wanted to do: these 17th century romances are derisive, mocking, filled with ridicule, picaresque adventure stories filled with ridicule for people of sensitivity, sensibility and all women in particular. Not until Balzac and Sand can this other vein of novel writing emerge triumphant and gain respect.

Mary McAlpin’s paper on Madame Roland’s memoir detailed how candidly, courageously Roland shows us herself coming to sexual as well as intellectual awakening. Roland vowed to hide nothing, and told of an incident of sexual harassment and abuse (her father’s apprentice exposed himself to her and attempted to get her to allow him to sodomize her—he didn’t get very far at all). Roland says the incident reinforced her determination to remain innocent until marriage: her emotional response to it, her mother’s (dense and guilt-tripping shaming) remarks, and her later memories provided her with protection. Paradoxically the incident was salutary and its effects remained even after she lost her religious faith (and guilt). She raised her daughter based on the idea it matters intensely what happens to a girl during puberty. I think Roland recognized around her a highly corrupt and nauseating approach to female biology, and thought of her own suppressions as the only way to keep her mind healthy and at peace. She could not say that explicitly, particularly after the venomous Marot began to say hideously ugly things about her sexual life.

I assume then that like me (and a couple of people on WWTTA), Roland would find outrageously thick-skinned Victoria Glendinning’s treatment of Virginia Woolf’s early trauma (in her biography of Leonard Woolf): "All girls have to have some first experience of male sexuality, and George’s late-night petting, however unsavory and unwanted, was no worse than most." I don’t know what to remark on more: Glendinning’s matter-of-fact idea men’s sexuality is usually abusive, and aggressive, and "all" girls "have" to experience this some time or other, or her idea that because she shrugged off such a thing, Virginia Woolf must’ve. I took Hermione Lee’s view that we see just "the tip of the iceberg" in the stories we are told for the Duckworth brothers had continual access to Virginia for years.

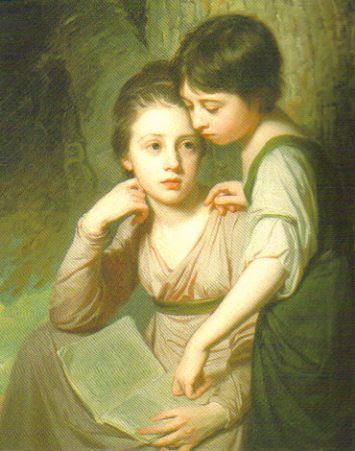

George Romney (1734-1802) Misses Cumberland (1772-73)

It seemed to me throughout all these papers that the women writers were writing about issues alive today in ways that speak home to women today.

I’ve one more set of summaries to create: on the sessions about Virginia Woolf I went to. I also want to describe the party given by the Virginia Woolf International Society Jim and I attended.

A toute a l’heure,

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Dear Dave,

These things are also a matter of taste. I find Wollstonecraft’s fiction hysterical in tone, and I find her Rights of Women can be hectoring. I love her Residence in Sweden. I was reading an excerpt yesterday.

For me content counts too: I half-remember Elizabeth Hamilton as utterly reactionary so I’d probably prefer Hays even if she never revised, and polished and produced the masterwork as Austen and Smith and Racliffe did.

Again, the problem with women’s memoirs before the mid-19th century is they do not think they have the right to write about themselves for real, and are only writing out of a desperate necessity, in each case different, or anguished appeal, or resentment, or attempt to get resitution, fend off shame—overwhelmingly the root cause is sexual aspersion and pariahdom which has brought on them various kinds of hard lives. To talk of scandal memoirs is to talk of women coerced into becoming serial whores.

I’m just now reading an excerpt from the memoirs of Mary Robinson. I’m appalled at how badly she was treated. She ended life a hopeless cripple. Forced into marriage 16, a horror of a husband, after a year and a half, dumped by this prince; the only relationship she had which was worth having (deep affection, loyalty, common intelligence) was with her daughter. We owe her poems and memoirs to her daughter.

In this era actress=available prostitute.

Before that I’ve been reading the other "scandal" memoirs. It’s a scandal all right but the scandal is how these women were treated. To me it’s obvious Eleanor Bowes wrote her Confessions of Countess Strathmore because her husband beat her into it and was standing over her. Phlippina Burton Hill tells of how she was humiliated and scapegoat out of: yes she was a fool to try to get patronage, but then she didn’t know where to turn.

Both of these were women who lost a place in their family.

We’re told of high spirits in Ann Sheldon: it’s the story of a rough and thick-skinned prostitute constantly being used, and then disappearing.

The only male to write similarly is Rousseau. Like them an outsider, without family to turn to, he tells the unspeakable in an appeal and was rejected intensely then and is critiqued harshly still by many. How dare he?

Two nights ago I almost finished Mansfield Park for the umpteenth time and late yesterday read an long excerpt from Ann Radcliffe’s travel book, A Journey Made in Summer of 1794. Together with Wollstonecraft, what a relief. Austen, Radcliffe, and Wollstonecraft were not only luckier. They took an attitude towards the world, themselves, and their writing that was high-minded.

It’s not just the woman lives on another plain of genius, but that this comes out of their self-conception, how they see their writing,its function. I realize this is a matter of taste and many would notsigh with relief as they begin to read Radcliffe’s analysis of war in middle Europe at the time from a strongly liberal-whig-protestant point of view but I do and the tone of Radcliffe’s mind in her travel book, Wollstonecraft’s in hers and her Rights of Women is closely reminiscent of Austen’s in Mansfield Park. Smith has this tone too.

Tellingly, 18th century women’s memoirs are still harder to get than 17th century women’s, though the 17th century woman will be super-pious, more reactionary, and write about her husband or be very discreet. The 17th century women’s are usually shorter; they were written by respectable women (or they weren’t saved); they are often pious (the ones which weren’t weren’t saved or were censored or destroyed). In the 18th century you get women of various classes writing at length and openly, openly complaining and protesting and telling truths about being beaten, losing property, how they came to be a prostiture, appealing, appealing, and yet trying to sell through sex too. They are usually long—3 volumes sometimes.

The 19th century clergymen who brought back the women’s memoirs wouldn’t go near many of the 18th century women. Today still I find people treat the women who write "scandal" memoirs as inferior (a scholar I just read referred to them as "that sort of woman").

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 17, 3:20pm # - P.S. On the Romney portrait:

At first you might not realize this is a portrait of two young girls reading a book. We don’t come away remembering the detail of the book so much not because it’s at the bottom of the picture space, but because we are deeply riveted by the older girl’s facial expression. She looks very troubled. She is pre-pubescent and has an adult

face. Perhaps something in the book has ignited some painful or disturbed memory.

I liken this one to a more famous one by Watteau called Iris, where we similarly see a pre-pubescent girl, only Watteau’s is clearly trussed up to be a sexual doll. To the sides of the girl are boys surrounded by visibilia which are symbolic of coming sexual penetration and trouble (the boys are squabbling, there is an iron implement).

In Romney’s the older Miss Cumberland is dressed in pseudo-Roman costume, so she too is got up the way the adults want. I like how the younger one is still engrossed in the reading. They make me remember the passage in Thackeray (Pendennis) where he says no matter how close we are or spend our days we are in separate universes. They also remind me of one by Gainsborough, of his daughters, only Gainsborough idealizes much more and doesn’t have a specific theme to attach the girl pair too. Romney’s young girls are much fleshier than Gainsborough’s.

We haven’t had Romney on our ECW groupsite space much. From my records (incomplete) it seems we’ve never had a picture by Romney on our groupsite space before. It’s not that I don’t like his pictures, but that he’s not emphasized in books and mine (like many others) have far more Gainsborough or Hogarth or Reynolds and he does not turn up in the French. That’s a shame.

Like Thomas Lawrence, Romney is associated with painting rich women and flattering them. Creating kitsche:

http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/r/romney/index.html

But that’s unfair; so did Gainsborough, Reynolds, in fact anyone who wanted to make a living as a painter.

He did do history paintings, and a couple are famous, e.g., The Death of General Wolfe:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Romney_%28painter%29

He often did very dramatic scenes from famous plays (Macbeth), rather like Fuseli though the depictions are much more conventional:

http://www.english.emory.edu/classes/Shakespeare_Illustrated/Romney.Tempest.html

He may be tarred by having painted Emma Hamilton so often, and as usual rumors arise they were lovers. Apparently he lived apart from his wife most of his life (as did Shakespeare).

He was a very fashionable figure, more fashionable than the more discussed painters today. Here is a book about him from Amazon.uk:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/George-Romney-1734-1802-Alex-Kidson/dp/1855143348

From an exhibition where he’s called a "forgotten genius" (not by those who buy reproductions of his [alas often worst] pictures:

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/walker/exhibitions/romneyg/

I will see if I can put more pictures on our groupsite space by him, like this intelligent thoughtful beautifully-painted one of the Misses Cumberland.

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 18, 12:03am #

commenting closed for this article