Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECS, Atlanta: Actresses (Cont'd) & poetry of the 1780s · 18 April 07

Dear Harriet,

My second morning at the American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies meeting held at Atlanta, Georgia a few weeks ago was utile et dulce.

First up (8 a.m.), was a panel on “Representing Theatrical Women: Continental Women & the Stage. As the first session had been about English-speaking women, this was about European women whose primary language and stage was not English. The first paper by Ms. Maria Park Bobroff, “Silvia, the Making Of,” was about an actress by origin Italian, who came to be seen as a quintessentially French player, Zanetta Benozzi. We know something of Benozzi’s real life as she left correspondence as well as records of her performances and private writing and public reviews praising her performances, and in her paper Ms. Bobroff tried to tease the truth about Benozzi’s appearance, her real character, and her life style by close examination of the plays Benozzi played in. The roles as Marivaux’s Silvia she was assigned include: the seduced young woman, the primitive and mythic (archetypes), and the seductor. Ms. Bobroff said the emphasis in all Benozzi’s roles was comedy, but she gradually changed the character of Silvia by projecting melancholy. For the most part this type is not a dupe of love, but someone who can manipulate others.

But it’s really hard to say what she was like. Ms. Bobroff suggested Zanetta Benozzi was able to project an aristocratic ideal, and seen as having a peculiar rapport with Marivaux’s texts. What was admired was Benozzi’s way of performing to please all. This makes me remember Austen’s Mr. Knightley’s comment to Emma about Frank: if he can indeed please all, can he be anything but a fawning superficial man in public; can he be sincere? Frank cannot be truly “amiable” in the English sense, not just “amiable” (all surface politeness) in the French? It was Casanova who described Benozzi as “a natural” and wrote a “touching” tribute to her in his memoirs. In addition, much of this maybe undermined by Grimm who Ms. Bobroff said contradicted this sort of media promotional self-flattery in his famous correspondence-journal: Grimm wrote Silvia projected sensitivity and naivete, but he was never conscious of her having any merit as an actress. He described her as having an unpleasant figure, an awful voice, and pretentious acting style; it was forced, false, tiring, and her character celebrated everywhere precisely what Grimm most disliked.

Be that as it may, the woman was apparently a financial and professional success. As with the session on actresses on the first day of the meeting, career success was the criteria here. I’ll add to the portrait that Benozzi was married, to Mario Balletti, brother of Benozzi’s rival, Elena Balletti who played Flaminia on stage. We cannot begin to know what sort of person she was, what was her character. In the question section, someone suggested that Benozzi’s Silvia was credited with the increasing marginalization of lewd comedy in her era.

Corinda Donato’s “Professionals not Whores: Defending Actresses in Eighteenth Century Italy,” demonstrated how hard it was to maintain respectability and the kind of sustained reputation Benozzi managed in public. Ms. Donato’s paper concentrated on issues of tolerance. First some background: The Italian stage differed from the English in that the actors were expected to improvise actions from a conventionalized repertory; English actors memorized scripts. One result on the Italian stage was where actresses were allowed and they played the role, they were seen as playing themselves transparently. Rimini was one place where you found women on stage: Goldoni had gone to Rimini and remarked that having women play women’s roles was superior to having “beardless” young boys or men play them. You could find women in disguise in places too: on the Roman stage singing (as castrati), and by wearing false penises. Apparently one woman who was killed upon inspection was discovered to be a female virgin who played and worked as a male servant.

On February 11, 1752, an Italian Enlightenment writer and respected scientist, Giovanni Bianchi (1693-1775), wrote and read a paper praising an actress, Antonia Cavalucci (1800-time of death unknown) who performed on Rimini stages The result was the opposite of what was intended. Instead of raising the status of actresses and this actress in particular, the paper reinforced the way actresses were treated as scandalous super-sexualized readily promiscuous women. While a respected cultural and scientific figure, Bianchi himself had earlier offended the church, and Antonia Cavallucci provided his enemies with a handle against him. Seething gossip denouncing him as lascivious and as allowing actresses to live in his house while they performed began to circulate. A book praising actresses was placed on the index. It is true that as contrasted to Isabella Canali Andrieni (1562-1604), who played chaste roles, Cavallucci tended to play sexualized promiscuous women types.

Ms. Donati told about the real life of Antonia Cavallucci: it included an early forced marriage to a man who beat her and did not himself earn money (but attempted to take hers); she left him, and travelled widely (with her mother at times), and left some letters. She called Bianchi “mio padre” or “nonno” as he treated her like she was his daughter or grand-daughter. The campaign against her was successful in the end. She died alone and in poverty in a hospital.

Ms. Donati’s story reminds me of how Sarah Siddons achieved respectability while other actresses (Dora Jordan, George Anne Bellamy) didn’t. Andreini was also married; her husband acted with her, and he edited and published her pastoral drama (Mirtilla, Lettere, Fragmenti), and two volumes of repertory pieces and a substantial body of poetry (Rime). Cavalucci who had just as hard a life but much less luck, was stigmatized and mostly forgotten. Bianchi’s decent effort backfired.

No good deed goes unpunished?

The last paper of the session was Anika Kiehne’s “Authorship, Editorship, and the Stage: Marianne Ehrmann’s Amaliens Erholungsstunden and Die Einsiedlerinnn aus den Alpen. Marianne Ehrmann was an actress, author, and editor, and among the earliest actresses the first to edit a periodical. What she experienced as an actress and editor tells us about the professional life of women in Germany. After her parents’ early death, she became a governess. She turned to the stage and endured a bad manager (and husband?); while she was well-received, she never became a great actress (I’d put it from George Anne Bellamy’s Apology, she never attained capital parts), and left the stage. With the help of her second husband, she turned to editing. She began as a self-publisher and so she and her husband had an important stake in this business of hers: their own money. She never had a child, and in effect, was partly the bread-winner of the pair.

Ehrmann seems to have turned to editing to pursue a more socially acceptable form of work for remuneration. Her writing is revealing. She tells tales of young girls who do not give themselves over to men. They seek an alternative companion in other young women. There are striking allusions to life on the stage: these are made up of women denied real education and place beyond inside a family. Ehrman visual imagery is theatrical, and she usually presents theatrical experience in a negative light. The plays were so crude, they made a deep impression on her emotions as she acted them out. She did advise educating young women to obviate any downfall, from sexual experience or marital choice. She situated herself in public space as a key to survival and self-fulfillment. She praises work, but what she means by work is different from the life of an author. She herself dreads and dislikes housework, but she also dreads the hardships a woman as a woman can experience.

Alas, the first periodical failed. Ehrmann tried again, and in the second was herself more overtly present. At the same time the state apparatus had become more rigorous (the establishment recognized a direct threat when they saw if), harassing. So she wrote her thesis, and found some of her directors were profondly reactionary.

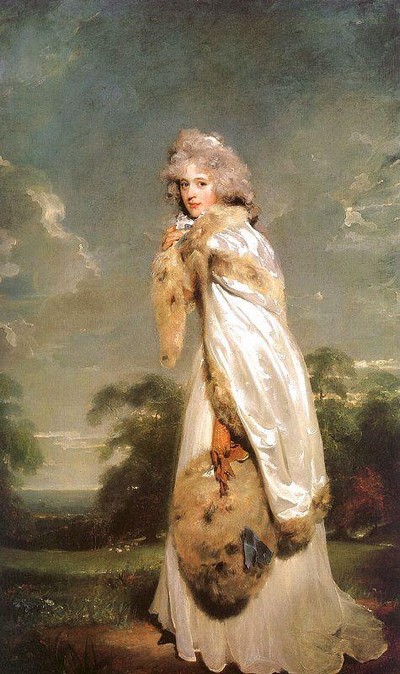

I do know of an Italian woman who did not start out as an actress but did become a successful editor: Elisabetta Caminer Turner, whose carefully self-censored writings (and thus very dull) have been published in the University of Chicago series throught the careful translations of Catherine M. Sama, who also edited and introduces the volume. She survived by marriage and caution. A rare successful actress, Elizabeth Farren (who married way up), has been celebrated recently by Emma Donoghue in her historical novel, Life Mask

Elizabeth Farren (1759-1829), painted 1790 by Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830)

The second session I attended that Friday was “Poets of the 1780s: Pre-Romantics.” The chair was Claudia Thomas who wrote a book on women poets reading Pope (which I bought while at the meeting) and declared the 1780s a liminal decade. There were papers on Joseph and the elder Thomas Warton, on Ann Yearsley and the scientific poetry of the 1790s (e.g., Erasmus Darwin).

This was just a delightful session. I can’t say I learned very much that I didn’t know before and am not summarizing the papers as basically they went through the lives of the chosen poets (easily found out if you have access to the ODNB or if you have any books from the early to middle decades of the 20th century), revalued (once again) topographical or landscape poems, and Cowper. It was just such a pleasure to hear the poems read aloud, especially the long Georgic type whom no one today but someone who truly loves reading would go near. I was like a Hobbit listening to the familiar stories of influence and mentorship, and appreciate close readings. A surveying of landscape is a surveying of the self; John Dyers’s early topographical georgic poems (which I cherish) became a source of philosophical elevation, are central to the history of meditative verse (which Ann Finch wrote too); in his ascent he experienced peace and joy.

What did I learn I didn’t know before? That the Wartons and William Lisle Bowles were in the same cohort, that the Wartons admired Bowles intensely, and themselves wrote a poetry of place. I knew they were all university men, that Thomas the elder wrote a history of poetry and study of Spender, and Joseph a book on Pope which made the mistake of defining Pope’s type of poetry as secondary because not deeply indwelling within solitude. All three men (there were two Thomases) wrote a universal poetry through going attempting to reach something spiritual in the character of local places.

The idiom the Wartons wrote in is the one Wordsworth succeeded

in destroying, but if, as you do in pictures, you can adjust yourself to a different schemata of metaphor, you will discern authentic ethical sensitive feeling communicated. First, Joseph Warton’s

To Evening

Hail meek-ey’d maiden, clad in sober grey,

Whose soft approach the weary woodman loves,

As homeward bent to kiss his prattling babes,

He jocund whistles thro’ the twilight groves.

When Phoebus sinks behind the gilded hills,

You lightly o’er the misty meadows walk,

The drooping daisies bathe in honey-dews,

And nurse the nodding violet’s slender stalk:

The panting Dryads, that in day’s fierce heat

To inmost bowers and cooling caverns ran,

Return to trip in wanton evening-dances,

Old Sylvan too returns, and laughing Pan.

To the deep wood the clamorous rooks repair,

Light skims the swallow o’er the wat’ry scene,

And from the sheep-cotes, and fresh-furrow’d field,

Stout plowmen meet to wrestle on the green.

The swain that artless sings on yonder rock,

His supping sheep and lengthening shadow spies,

Pleas’d with the cool, the calm, refreshful hour,

And with hoarse hummings of unnumber’d flies.

Now every passion sleeps; desponding Love,

And pining Envy, ever-restless Pride,

And holy calm creeps o’er my peaceful soul,

Anger and mad Ambition’s storms subside.

O modest evening, oft’ let me appear

A wandering votary in thy pensive train,

List’ning to every wildly-warbling throat

That fills with farewell notes the dark’ning plain.

The same idiom, but in real weariness or depression, Sonnet I from William Lisle Bowles’s sonnets:

Written at Tinemouth, Northumberland, after a Tempestuous Voyage

As slow I climb the cliff’s ascending side,

Much musing on the rack of terror past,

When o’er the dark wave rode the howling blast,

Pleas’d I look back, and view the tranquil tide

That laves the pebbl’d shore: and now the beam

Of ev’ning smiles on the grey battlement,

And yon forsaken tow’r that Time has rent:

The lifted oar far off with silver gleam

Is touch’d, and hush’d is all the billowy deep!

Sooth’d by the scene, thus on tir’d Nature’s breast

A stillness slowly steals, and kindred rest;

While sea-sounds lull her, as she sinks to sleep,

Like melodies which mourn upon the lyre,

Wak’d by the breeze, and, as they mourn, expire!

And last the elder Thomas’s

Lines written after seeing Windsor Castle

From beauteous Windsor’s high and stoned halls,

Where Edward’s chiefs start from the glowing walls,

To my low cot, from ivory beds of state,

Pleased I return, unenvious of the great.

So the bee ranges o’er the varied scenes

Of corn, of heaths, of fallows, and of greens;

Pervades the thicket, soars above the hill,

Or murmurs to the meadow’s murmuring rill;

Now haunts old hollowed oaks, deserted cells,

Now seeks the low vale-lily’s silver bells;

Sips the warm fragrance of the greenhouse bowers,

And tastes the myrtle and the citron flowers;

At length returning to the wonted comb,

Prefers to all his little straw-built home.

In his presentation W. B. Gerard described and expatiated upon Ann Yearsley’s long georgic Clifton Hall movingly. He said she presented her poem as unashamedly personal. (So Charlotte Smith was not the only woman poet to do this.) Her hero seems not to be in control of his mind or identity—we can see how the latter theme would be a projection of her uncertain sense of self, given her genius, self-education but low status and daily job as a milkwoman and having to live with an uneducated man as his obedient wife-servant who is there to provide him with children and bring them up. I can imagine how galling it was to be condescended to by Hannah More and see More attempt to control the small monies Ann had made from her books. Ann Yearsley also includes in her poem a sense of how she has to clean intensely hard at low tasks (cleaning someone else’s house). He showed how Yearsley mixes local and privileged motifs. Here is one of her sonnets:

To … (or untitled)

Lo! dreary Winter, howling o’er the waste,

Imprints the glebe, bids every channel fill

His tears in torrents down the mountains haste,

His breath augments despair, and checks our will!

Yet thy pure flame through lonely night is seen,

To lure the shiv’ring pilgrim o’er the green

He hastens on, nor heeds the pelting blast:

Thy spirit softly breathes—”The worst is past;

Warm thee, poor wand’rer, ‘mid thy devious way!

On thy cold bosom hangs unwholesome air;

Ah! pass not this bright fire! Thou long may’st stray

Ere through the glens one other spark appear.”

Thus breaks thy friendship on my sinking mind,

And lures me on, while sorrow dies behind.

She led a much harder life than the Wartons or Bowles.

Gerard also quoted from and expatiated on Lewis Crowe’s Lewiston Hill and Cowper’s Task.

Joann Kleinneiur’s “Chemists in the British Parnassus: Natural Philosophical Poetry of the 1780s.” She discussed and quoted from an array of English poets of the 1790s, who used the process of growth and development of specimens as well as their experiences for observation. Ms. Kleinneiur showed a knowledge of chemistry (developed in our own time) is embedded in the metaphors developed in our own time.

*******

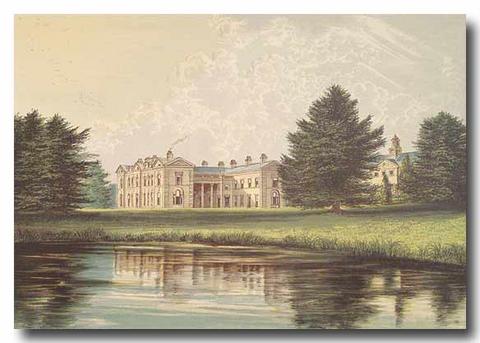

Here I am back on a beautiful Friday evening. Jim and I are about to go off to the Austrian embassy to listen to an evening of Brahms and Wolf’s songs, and I conclude this letter with an image of the ideal home and landscape as envisaged in a colorized later 18th century print:

Compton Verney House, Warwickshire, 18th century mansion built by George Verney, 12th Lord of Willoughby de Broke, now an art museum and research library

Some such image of a mansion and picturesque grounds was in Austen’s mind when she dreamed of Pemberley. The whole zeitgeist as pictured influenced the romantic poets of the 1780s: their ideal was not rough, primitive, peasant-like places and culture, but the cultivated, the artificially beautiful, what resulted from wealth and scientific understanding. Yes such things are debased in many people’s hands, and used for competition and to intimidate and as sites for self-aggrandizement and admiration and gaining power, but I can admit they are beautiful too. What is it Mrs Gardiner says to Elizabeth Bennet at the end of her letter as she imagines Elizabeth’s coming marriage to Darcy:

“I shall never be quite happy till I have been all round the park. A low phaeton, with a nice little pair of ponies, would be the very thing …” (P&P, 3:10).

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I put the following on EighteenthCentury Worlds at Yahoo on 4/25/07:

This one is appropriate for a beautiful spring day (we are having one in Alexandria, Va, right now). I thought of it because Dyer’s poetry is an early precursor of poetry of the 1780s which dwells at length on landscape and reverie.

It was this kind of poetry I liked so very much when I first decided to major in the eighteenth century. It anticipates the picturesque painting of the later part of the era, Wordsworth’s use of poetry as therapy; echoes of it occur throughout the century. It’s colorful, intimate, allegorical; the politics are conservative by implication but the poem is intended to be non-political and in the 18th century sense is: no one is mentioned, no faction, no cause. I like the vein of intense if subdued melancholy and was attracted by Dyer's insistence on having low expectations as the only way to find peace.

Grongar Hill

John Dyer

Silent Nymph, with curious eye,

Who the purple ev’ning lie

On the mountain’s lonely van,

Beyond the noise of busy man,

Painting fair the form of things,

While the yellow linnet sings;

Or the tuneful nightingale

Charms the forest with her tale;

Come, with all thy various hues,

Come, and aid thy sister Muse;

Now, while Phoebus, riding high,

Gives lustre to the land and sky,

Grongar Hill invites my song,

Draw the landskip bright and strong;

Grongar, in whose mossy cells,

Sweetly musing, Quiet dwells;

Grongar, in whose silent shade,

For the modest Muses made,

So oft I have, the ev’ning still,

At the fountain of a rill

Sate upon a flow’ry bed,

With my hand beneath my head;

While stray’d my eyes o’er Towy’s flood,

Over mead, and over wood,

From house to house, from hill to hill,

'Till Contemplation had her fill.

About his chequer’d sides I wind,

And leave his brooks and meads behind,

And groves, and grottos where I lay,

And vistas shooting beams of day:

Wide and wider spreads the vale,

As circles on a smooth canal:

The mountains round, unhappy fate!

Sooner or later, of all height,

Withdraw their summits from the skies,

And lessen as the others rise:

Still the prospect wider spreads,

Adds a thousand woods and meads,

Still it widens, widens still,

And sinks the newly-risen hill.

Now, I gain the mountain’s brow,

What a landskip lies below!

No clouds, no vapours intervene,

But the gay, the open scene

Does the face of nature show,

In all the hues of heaven’s bow!

And, swelling to embrace the light,

Spreads around beneath the sight.

Old castles on the cliffs arise,

Proudly towering in the skies!

Rushing from the woods, the spires

Seem from hence ascending fires!

Half his beams Apollo sheds

On the yellow mountain-heads!

Gilds the fleeces of the flocks,

And glitters on the broken rocks!

Below me trees unnumber’d rise,

Beautiful in various dyes:

The gloomy pine, the poplar blue,

The yellow beech, the sable yew,

The slender fir, that taper grows,

The sturdy oak, with broad-spread boughs;

And, beyond, the purple grove,

Haunt of Phyllis, queen of love!

Gaudy as the op’ning dawn,

Lies a long and level lawn,

On which a dark hill, steep and high,

Holds and charms the wandering eye!

Deep are his feet in Towy’s flood,

His sides are cloth’d with waving wood,

And ancient towers crown his brow,

That cast an aweful look below;

Whose ragged walls the ivy creeps,

And with her arms from falling keeps;

So both a safety from the wind

In mutual dependence find.

‘Tis now the raven’s bleak abode;

‘Tis now the apartment of the toad;

And there the fox securely feeds;

And there the pois’nous adder breeds,

Conceal’d in ruins, moss, and weeds;

While, ever and anon, there falls

Huge heap of hoary moulder’d walls.

Yet time has seen, that lifts the low,

And level lays the lofty brow,

Has seen this broken pile complete,

Big with the vanity of state;

But transient is the smile of Fate!

A little rule, a little sway,

A sunbeam in a winter’s day,

Is all the proud and mighty have

Between the cradle and the grave.

And see the rivers how they run

Thro’ woods and meads, in shade and sun!

Sometimes swift, sometimes slow,

Wave succeeding wave, they go

A various journey to the deep,

Like human life to endless sleep!

Thus is nature’s vesture wrought,

To instruct our wand’ring thought;

Thus she dresses green and gay,

To disperse our cares away.

Ever charming, ever new,

When will the landskip tire the view!

The fountain’s fall, the river’s flow,

The woody valleys, warm and low:

The windy summit, wild and high,

Roughly rushing on the sky!

The pleasant seat, the ruin’d tow’r,

The naked rock, the shady bow’r;

The town and village, dome and farm,

Each give each a double charm,

As pearls upon an Ethiop’s arm.

See on the mountain’s southern side,

Where the prospect opens wide,

Where the evening gilds the tide;

How close and small the hedges lie!

What streaks of meadows cross the eye!

A step, methinks, may pass the stream,

So little distant dangers seem:

So we mistake the Future’s face,

Ey’d thro’ Hope’s deluding glass:

As yon summits soft and fair,

Clad in colours of the air,

Which to those who journey near,

Barren, brown, and rough appear;

Still we tread the same coarse way;

The present’s still a cloudy day.

O may I with myself agree,

And never covet what I see:

Content me with an humble shade,

My passions tam’d, my wishes laid;

For while our wishes wildly roll,

We banish quiet from the soul:

‘Tis thus the busy beat the air;

And misers gather wealth and care.

Now, ev’n now, my joys run high,

As on the mountain-turf I lie:

While the wanton Zephyr sings,

And in the vale perfumes his wings;

While the waters murmur deep;

While the shepherd charms his sheep;

While the birds unbounded fly,

And with music fill the sky,

Now, ev’n now, my joys run high.

Be full, ye courts; be great who will;

Search for Peace with all your skill:

Open wide the lofty door,

Seek her on the marble floor:

In vain ye search, she is not there:

In vain ye search the domes of Care!

Grass and flowers Quiet treads,

On the meads, and mountain-heads,

Along with Pleasure, close ally’d,

Ever by each other’s side:

And often, by the murm’ring rill,

Hears the thrush, while all is still,

Within the groves of Grongar Hill.

John Dyer (1699-1757) was supposed to go into the law (as so many gentry people and above wanted their sons too), but upon his father’s death he became a wandering painter. Welsh, he did eventually give in and took positions as an Anglican clergyman (probably from family interest) to survive (and live comfortably). I like his Ruins of Rome and The Fleece (a georgic). “Grongar Hill” was published 1726, the year of Thomson’s The Seasons.

Here is a life at Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dyer

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 25, 8:29am #

commenting closed for this article