Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECS, Atlanta: Women & Wit, French moralistes, & Scheherazade · 23 April 07

Dear Harriet,

The second morning at the American Society for 18th century studies at Atlanta went on until 1 o’clock, and I had chosen well for the 11:30 to 1 slot: “Women and Humor in the 18th Century.

Although my question afterwards may have seemed to disagree with Peggy Thompson’s stance in her paper, “She Would if She Could; or, Why Lady Wishfort isn’t funny,” in fact I rejoiced to hear someone speak who feels just the way I do when I read cruelly misogynistic plays and am told I have no sense of humor or am being politically correct when I don’t laugh. I don’t find venomous satire directed at unreal stereotypes and dependent upon a morality which assumes bullying and hypocrisy are unchangeably at the core of most people’s behavior funny. (I don’t like slapstick either. Why should I laugh at someone falling down and humiliated by the fall?)

Ms. Thompson’s paper “cautioned us against enjoying the many women characters in Restoration and 18th century comedies who are presented as dying for sex on any terms with men and hypocrites about it. Lady Wishfort is an ultimate depiction of insincere resistance to a man by a woman who desires him. Ms. Thompson said “such characters exemplify the performative production of insincerity.” There are many such women characters in the dramas of this era: they include lustful cock-teasers whose rare virtues are therefore subject to cynical interpretation. In such plays the pretense of avoiding detachment becomes a way of avoiding responsibility for aggression. The women are unsavory metaphors for grotesque desire. Ms Thompson alluded to Congreve’s song where the laborious pursuit of such a woman (for money?) is no pleasure.

Another type of women in the drama of this period is the virtuously and ambituously resisting woman. Now concealment of real desire nearly paralyzes the virtuous woman.

These tropes have an insidious appeal for the mass audience. They enact and insist on an adversarial relationship between people. The laughter reinforces the idea that women love men who chase them.

Diana Solomon talked about Nell Gwyn and “the ‘Reviv’d Epilogue.” The most famous example comes from John Dryden’s Tyrannic Love, first played in 1770. Nell Gwyn plays the impossibly virginal martyr who never had a sexy or resentful thought in her life. Naturally she was murdered by the state.

Epilogue Spoken by Mrs. Ellen, when she was to be carried off dead by the Bearers.

To the Bearer.

Hold, are you mad? you damn’d confounded Dog,

I am to rise, and speak the Epilogue.

To the Audience.

I come, kind Gentlemen, strange news to tell ye,

I am the Ghost of poor departed Nelly.

Sweet Ladies, be not frighted, I’le be civil,

I’m what I was, a little harmless Devil.

For after death, we sprights, have just such Natures,

We had for all the World, when humane Creatures;

And therefore I that was an Actress here,

Play all my Tricks in hell, a Goblin there.

Gallants, look to’t, you say there are no Sprights;

But I’le come dance about your Beds at nights.

And faith you’l be in a sweet kind of taking,

When I surprise you between sleep and waking.

To tell you true, I walk because I dye

Out of my Calling in a Tragedy.

O Poet, damn’d dull Poet, who could prove

So sensless! to make Nelly dye for Love,

Nay, what’s yet worse, to kill me in the prime

Of Easter-Term, in Tart and Cheese-cake time!

I’le fit the Fopp; for I’le not one word say

T’excuse his godly out of fashion Play.

A Play which if you dare but twice sit out,

You’l all be slander’d, and be thought devout.

But, farewel Gentlemen, make haste to me,

I’m sure e’re long to have your company.

As for my Epitaph when I am gone,

I’le trust no Poet, but will write my own.

Here Nelly lies, who, though she liv’d a Slater’n

Yet dy’d a Princess, acting in S. Cathar’n.

This type of highly satirical epilogue undercut the basic mood of a tragic play, cast cynical light upon the virtuous long-suffering heroine, and played upon the audience’s knowledge that it was a certain actress playing the role and the distance between her real life character and that of the play It was popular in many variants on the Restoration and early 18th century stage, e.g., Anne Finch’s Epilogue to Rowe’s Jane Shore, intended to be spoken by Ann Oldfield, and Budgell’s Epilogue to Philips’s The Distrest Mother, also intended to be spoken by Ann Oldfield.

Ms. Solomon said the “body” of the actress” moved from “a source of pathos to sexual spectacle.” “The heroine’s plight is turned into the bizarre.” There were at least 35 such epilogues after Nell Gwynn’s in Tyrannic Love. Great actresses were able to move swiftly between these reverse stereotypes as well as exploit the distance between themselves and their character. Such epilogues functioned to advance the actress’s reputation: Nell Gwynn was vaunting her use of her status to enact a princess, & pleased because she identified with working and ordinary people.

The influence of these epilogues may be seen in the work of Percy Fitzgerald, a 19th century critic, who was among the first to tell a tale of how Charles II fell in love with Nell Gwynn after attending to the above epilogue in the theatre. The story does deprive Nell of agency.

The last two papers were about women and humor in the later 18th century. Christopher Reese talked about the uses of humor by women in the later novels, and Tara L. Hunt named names and described real practices of women publishers who printed caricatures. The paper was a historically informative discourse on women printers and makers of caricatures from the later 18th through early 19th century. Ms. Hunt also described the work of women who produced other kinds of humor in travel writing. In the 19th century the market for prints was dominated by publishers with layers of resources & a distribution mechanism. She felt there was a condemnation of public women, especially satirists and those who did caricatures: they were presented as grotesque (this is so in Trollope). “Natural” women do not enjoy politics at all, and increasingly the public woman was assumed to be willing to sell her body. Ms. Hunt found a fear of comic women: they should not make jokes was the mantra.

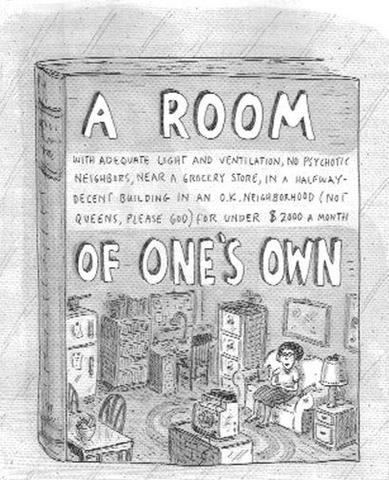

We are in the twentieth century gotten over that to some extent. Here Roz Chast laughs at Woolf’s famous solution for women as interpreted today:

Roz Chast, the New Yorker, March 2007

After lunch we heard the first plenary speech: Felicity Nussbaum’s on The Arabian Nights. She deconstructed the tales both in their original state and in their eighteenth-century versions to show how much prejudice against black and asian people is to be found therein. The historical content of her talk consisted of a retelling of the history of early 18th century publication, including precisely what was in the edition and as far as we can know where the texts came from. There is no written original for Sinbad the Sailor and Ali Baba. Tellingly, the most popular tales since the 18th century are ones added on by Europeans at the time. Aladin and his magic lamp is but one. The 18th century texts are highly stylized, freely colloquial European stories which manifest anxiety over the relationship of women in the harems and black slaves.

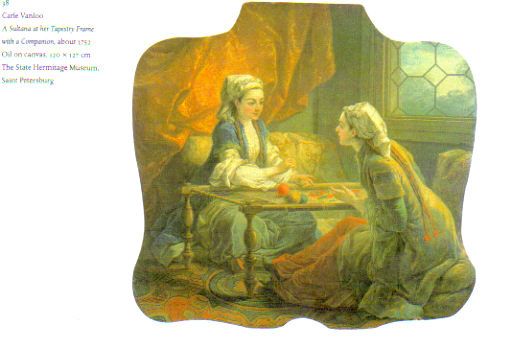

Carl Van Loo (1705-1765) Sultanessa at Tapestry Frame, mid-18th century, commissioned by Madame de Pompadour

What she outlined reminded me of what I felt when reading Montesquieu’s Persian Letters. I noticed near me a few people nodding off. This was not (I thought) because the speech was dull. Perhaps the room was so crowded and people tired. I asked a couple of people afterwards what the phrase “Arabian Nights” immediately conjured up, and they said their knowledge of the Arabian Nights came from the kind of book intended for children I read when young (colorful illustrations were part of what drew me). It seems to me adult western people still think of the Arabian Nights as something from their childhood, escape adventure stories, with little psychological complexity. Jim said all he knew of the Arabian Nights was what he saw presented in Christmas pantomimes in England where Widow Wanky was a dominating figure on the stage.

What kept me up was waiting to hear about Scheherazade who remains an alluring figure for women writers to identify with. Several 18th &19th century women writers mention or identify with her (Isabelle de Montolieu, Maria Edgeworth, Jane Austen, Elizabeth Gaskell); in the 20th century Isak Dinesen has recreated the Arabian tale in sophisticated pessimistic parables of great power. Perhaps you’ve seen the film adaptation of her Babette’s Feast? Alas, Prof. Nussbaum’s dissection of the racism and sexism in this famous text did not lead her to discuss Scheherazade or how the deadly and imprisoning sexism of the Arabian Nights relates to how western women writers and readers have used Scheherazade as an icon for themselves when they write. Nor did she go into how a woman would feel reading these stories or how they were used by women (and men) in moral tales.

Elin Danielson (1861-1919), Reading Time (1890)

Prof. Nussbaum was more interested in racism and exposure how the Arabian Nights is post-colonial.

The last session of the day, “Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History,” on French women writers, was, like the session on French women writers I attended the next day, “The Wedding Night” (which I’ll describe in my next blog letter on the ASECS, Atlanta) among the most exhilarating I attended because afterwards the people in the room engaged in genuine dialogue, asked searching questions, offered more examples, and did not appear to worry about how their status was affected by what they said.

The first speaker was Julie Chandler Hayes. She discussed the collection of tales, and in particular Madeleine de Scudery (1607-1701) Ms. Hayes described Scudery’s romance and conversastions as having a “euphoric socialability,” and yet are filled with debates without winners where the characters are not able to break out of their egoism to understand one another. In Scudery’s books we imbibe philosophical themes become personal statements. Of her characters, Celinte does not manage to attain the wise tranquillity of age; two women in another dialogue appear to learn little form one another. In these writings Scudery is a poised courtier, anticipating La Rochefoucauld. What does she say and what does she teach? Friendship cannot be non-problematic; Scudery emphasizes historical or realistic experience; she show how differently women of a different age see the world.

Ms. Hayes also described similar writings by Anne-Thérèse de Marguenat de Courcelles, Marquise de Lambert (1647-1733), Emilie du Chatelet (1706-1749), and Madeleine de Puisieux (1720-1798). Lambert’s dialogues are more sombre, loss is emphasized, tells of women approaching an age where they fear losing everything that made life dear. The tone is bleak, as Lambert tells of privations of age, the solitude you must learn to live in. She meditates life, and advises the reader to make use of time, and remember it’s a gift in old age when people do at last begin to have the ability to live in the present.

Emilie de Chatelet’s “Discours du Bonheur” was analyzed. It’s meant as personal experience, not an epistemology of the era. In the treatise Chatelet emphasizes the importance of passion and detachment. One source of happiness for her was gambling which she felt made her feel herself to be alive intensely; it gave an enhanced sense of the present. To gain true “gloire” the route is study, eruditino, and then writing. You must do these for their own sake, yet she longs for applause from posterity, for recognition, all the while knowing how precarious dependence on the opinions of others make happiness precarious. One must find some space between hope and fear.

In her Characters (1749) Pusieux portrays herself as a moraliste refashioning herself. We feel a strong sense of intelligence in this woman. She produced a misconduct book about the vast territory of the feminine condition, a one-sided epistolary novel where she tells tales about her life. Her speaker is an older wiser women who had taught Pusieux in a convent. The figure we identify with is queried wittily by a male friend; and shows him her manuscript. Pusieux was in her late 20s, and yet wrote confidently in this genre about what to read, who to trust, how to manage you life with your lover—although her previous work had been misattributed. She cautions her readers against a literary career if they value peace of mind and reputation.

The book ends on a bitter note of discouragement, and fear of “the other.” Nonetheless she grew through her book. The object of pupil and teacher alike is knowledge, which must be distinguished from mere unexamined sensation. To gain this, we must encounter ourselves apart from others.

The second paper, on Felicite-Stephanie de Genlis (1746-1830), by Vicki Mistacco, was filled with information about Genlis’s attitude towards literature and stout-hearted defenses of herself against fierce critics. These critics hoped to silence her by ruthless detraction, particularly after she wrote her De l’influence des femmes sur litterature francaise comme protectrices des Lettres ou comme auteurs (1811), a compilation of biographies, from Ragamunde to Sophie Cottin.

De l’influence des femmes sur la litterature francaise is a compiliation of biographies from Ragamune to Sophie Cottin (1780-1807). It’s the last avatar of the old sort of book called Femmes illustres; Christine de Pisan did one; more recently two other French women writers had tried to compile a list and write the lives of women writers. De l’influence des femmes sur la litterature francaise had begun as a project she was invited to participate in, but she broke off from the terms of the original idea and worked on alone to challenge cultural stereotypes.

Genlis limited the group to women who she thought respected modesty, decency, good taste and religion. She assessed them by their morality. Germaine de Stael is presented as the epitome of all Genlis loathed; she stigmatizes Julie de Lespinasse (1732-1776) for her candid, desperate, openly vulnerable and begging love-letters to M. Gibert (published in 1809); Genlis disliked romanticism. Her argument is women’s abilities are equal to those of men; we do not see this because they are deliberately poorly educated. She places women moralists above Marivaux and D’Alembert. She judges literature by a different scale of values than those of established institutions. Genlis was demanding recognition for women writers for civic activities too. A woman who is sensible (the word is meant in the 18th century sense of having strong sensibility and sensitivity) need not be weak. There are bitterly ironic denunciations of things she has seen based on her personal experience. She attacks Madame de Lafayette (the author of La Princesse de Cleves).

The book reaches beyond the woman themselves to to talk about the conditions of writing and she described a male hegemony which begins with schools for boys and what books children are set to read. She showed how pedagogical anthologies slight women, and includes 80 pages of damning Telemachus by Fenelon with faint praise. This latter was a text repeatedly set for children as exemplary, and it was made to serve as a springboard for boys’ education. She wants to rehabilitate Madame de Maintenon (1636-1719) who had founded St. Cyr, and make Maintenon’s writings and attitudes a standard for education. This part of the book provided the chief fodder for the vehement attacks the book received. She had irritated liberal as well as conservative critics; she was a standing rebuke to the new ideal for women promulgated in the Napoleonic era and by Napoleon himself: women must be submissive.

She herself ended on a note of patriotic zeal: Napoleon had helped her to survive, by (among other things) providing her with an apartment, but around this time she gave up her apartment where she had had easy access to books and held a Saturday salon.

She wrote her Reflections on her book after the appearance of a 2 volume diatribe against her. The was an 84 page roar against her favoring women, and accused her of doing this as a sales gimmick. She was called an Amazon. In her Reflections she addes many new names and quotations of long passages of writing by women. She has a strong right to final speech. Her autobiographical identification with Madame de Maintenon (about whom she wrote an autobiographical novel) was intense. But still her book was not treated as a feminist one by those who defended it; for example, an English translation framed it as anti-Jacobin. In a way what she leaves out is literature or art: she does not dwell on the imagination or account for her writing the actual content of her novels. All she says is a book must be moral and pithy.

The respondent on the panel was Lesley Walker, and she attempted to set the papers into a framework of a new stage of reflections on women’s participation in art and public life both at the time of the French women writers and now. She suggested feminist historiography moved from listing, naming, and defending women’s accomplishments, to a complicated view of women’s predicament. Ms. Walker wanted women now to keep a complicated perspective up without assuming women have an abject predicament. Here she reminded me of the women in the first and second days’ sessions on actresses who had chosen and admired their subjects for their career success. She argued women now need to reconfigure the paradigms worked out from the 1970s through 1990s, and have a new view of women’s writing which did not show them as victims.

The French moralist tradition which women contributed to can aid in this project. The womens’ perspective derives form the material conditions of women’s lives, and she felt Scudery in particular anticipates today’s understanding of the importance and value of time in women’s experience. By contrast, society does not value aging in women because it’s the beauty of their bodies that men prize.

Genlis misbehaved, and remains relatively unknown. She came from an impoverished provincial family, and was a musical prodigy as a girl. Her mother pushed her into society, and showed her how to ingratiate herself, and she managed a spectacularly upwardly-mobile marriage, then became mistress to the Duke d’Orleans, and the governess of his son who became Louise Philippe in 1831. Louis Philippe is said to have told Victor Hugo that Madame de Genlis made him a man. (Whatever that means.) Her writing consists of volumes of didact treatises, plays, novels, biographies. She fled the revolution, for she would have been guillotined swiftly, and then, like Talleyrand (only not powerfully, rather marginally) insinuated herself into the new Napoleonic cliques. She saw herself as an important player, and became a violent critic of romanticism. She argued women participate in the literary canon as a patriotic mission, but at heart she wanted to write French literary history in the ways Walter Scott was writing English-Scots literary history.

Ms. Walker said nobody reads Genlis. Genlis never talked about her own writing except to say I did it better than this or that other writer. She does not discuss literary values, only will make general statements like Madame de Lafayette’s art is the greatest among women. Her polemic is moral and conservative and her footnotes are little polemics. She objects to plagiarism without any sense of historical intertexuality, and routine copying from historical sources. It is true that we can discern a conscious tradition of women’s writing among women since they cite one another.

The chair of the panel, Nadine Berenguier then opened the discussion for everyone to participate in. It was the kind of inspired quick conversation which when gotten down in notes will not seem to have much content, but it was rejuvenating and I think original and frank.

I remember my comments: I told them Genlis was known in later 18th century England, was continually translated and quoted; I reminded them of how Ellen Moers in her Literary Women devoted a whole chapter to the heroine or exemplary woman as teacher and governess, and argued that Genlis was central to this tradition and was not forgotten. Genlis combined the roles of Scheherazade and Maintenon. I mentioned Julia Kavanagh (1824-18877), a 19th century woman letters, travel-writer, critic and autobiographer, an English woman who was deeply attracted to French and wrote books which brought the two traditions together (anticipating Edith Wharton in this). Kavanagh compiled biographies of English and French women of the 18th century, and suggested that perhaps some of the matter of her lives from Madame de Gournay to Madame de Stael was taken from Genlis’s book. I said I had found it just about impossible to read De l’influence des femmes sur la litterature francaise in the US unless you have access to a superb research library as it is not often found even in the best ones in the US. It is not included in Gallica, only the much shorter reflections. So I had never been able to compare Genlis’s with Kavanagh’s texts to see if Kavanagh had turned back to use Genlis. If so, and if we could compare them as we went, well, English readers could then reach Genlis’s book through Kavanagh.

When they moved on to discuss the young v age perspective in Scudery, I suggested that the conflicts they spoke of between young and old women which were another rift in the women’s movement do not just come from young women not understanding older ones nor being able to see life from their standpoint, but an older woman (like myself I said) sometimes forgets what she so desired when young, what were her passionate ideals and terrible justified fears for her future then.

On Emilie du Chatelet all I could think myself (I didn’t say it) was how wonderful she openly defended her pleasures in life.

Emilie du Chatelet

Oh what a session that was. Worth coming to Atlanta for. On Thursday I’ll tell about the third day when I went to a session on interior arts, and one on French women’s texts (centered on the theme of the wedding night); I also gave my paper on Anne Halkett in a paratexts session.

A toute a l’heure, my dear,

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article