Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

The Victorian Age at the MLA, 2007 · 10 January 08

Dear Harriet,

At the MLA this year, over half the sessions I went to were on some aspect of the Victorian age. I cannot afford in the spring to go to both the Eighteenth Century meeting (ASECS) in Portland, Maine, and the North American Victorian Association meeting (NAVSA) in Toronto. Happily, the papers in the sessions I went to were mostly excellent, and in order to remember a few of them and to report to the curious what was said, I transcribe some of my stenography notes from the Thursday and Friday sessions here.

On Thursday evening I went to two Victorian sessions. The first, “Mid-Victorian Self-Assessments: Images of the Victorian Age” (5:15 pm), consisted of three papers. On the Great Exhibition of 1861 sometimes (she said) called “The Fairy Palace,” Molly Hilliard discussed the enormous amoung of fairy imagery and tales found in many Victorian texts, from paintings and poetry, to writings about foreigners (non-English people) and depression (where fairies are used to depict unhappiness and nightmares). In “Shattered Glass: Autobiography, Commodity, and the Portrait of an Age,” Sean Christopher connected the great increase in the number of published autobiographies to the popularity of the genre and the amount of money one could make selling one. He argued the main (or even only) reason someone would publish his or her private life would be financial profit. He said that before 1820 most autobiographies had been lives of great men, and the sudden increase in travel books, memoirs, religious lives, and letters was a writer could make his or her life into a commodity. Shalyn Claggett’s paper on Victorian popular science was on phrenology, and she connected its pseudo-scientific attempt to explain and predict stories of people’s lives with popular science on the brain today.

I did not have a chance to speak. Had I been called on, I would have partly disagreed with Mr Christopher. My researches show me there were many autobiographies about all sorts of people (women too), beginning in the 17th century and that motives were various. While publication is the only way to make money on such texts, & they did become a commodity once there was a capitalist marketplace to sell books throuhg, there are many examples of writers who want to express themselves fully (Rousseau), memorialize their every minute (Boswell and Burney), and work out all sorts of conflicts and needs through writing for themselves (in diaries) and to others. It’s true that someone who wants a successful professional career had better be careful about what they tell about themselves; however, many people before, during, & since the 19th century have not had an opportunity to or shown that they want to be controlled by a professionally-respectable image. If you read autobiographies of those Victorians who said they were writing for money (e.g., Trollope and Oliphant), you find many other motives at work, compensation, the desire to control their image, grief, loss, a desire to retrieve and recreate a life they might want to have lived. James Olney’s volume, Autobiography: Essays Theoretical and Critical bears out my contention (see especially Georges Gusdorf).

I expected “Life, Debt, and Death: The Victorian Businessman” (7:00 pm) to include papers which would at least occasionally mention Anthony Trollope. In the event, he was a major figure in two of the papers. In “Pattern Men: Paradoxes of Character in the Victorian Business Biography,” Aeron P. Hunt shows that lives about business men proliferated in the era, and that the earlier ones tended to be far more realistic than the later ones which romanced and idealized the characters of businessmen. Many biographies which presented men of high ethical character had as their agenda an attempt to stop government regulation and support a laissez-faire marketplace; they often lacked in-depth psychology while they followed novelistic conventions. A novel like Trollope’s The Way We Live Now would then have told more truth than these non-fiction books, even if the non-fiction books were about real men who lived and gave information about them (e.g., one on William Arthur which did emphasize his private characer). Carlyle’s essay against erecting a statue to a businessman (George Johnson) was very out of kilter with what was found in public media.

Nancy Henry’s “Suicide and the Financier in Victorian Culture” eventually centered on Trollope’s depictions of businessmen who commit suicide or end up in anguished circumstances. She began with what she said was the myth legends of businessmen committed suicide in 1929, spoke of Barbara Gates’s idea that in novels suicide becomes an allegorical trope for justice, mentioned suicide in Dickens, Wharton, and Gissing, and ended on a discussion of Trollope’s Josiah Crawley & Dobbs-Brougton (The Last Chronicle of Barset), Ferdinand Lopez (The Prime Minister), & George Vavasour (Can You Forgive Her?).

G.H. Thomas, The suicide of Dobbs-Broughton, from the original illustrations of Last Chronicle of Barset

Rebecca Stern’s paper presented fascinating pictorial depictions of “Debt and Decor: Business, Men, and the Well-Appointed Home.” She suggested many Victorian businessmen regardd house decorations as a form of investment, and wanted to show their character and success by having a luxurious home. Illustrations of the era, though, often show people going foolishly into debt and present grotesque nightmares, families about to have their household auctioned off, men ending up in prison. From novels she discussed Melmotte in The Way We Live Now (who demonstrates his wealth by his well-appointed home), crooks in Dickens’s Nicolas Nickleby, fraudulent advertising in Trollope’s The Struggles of Brown, Jones, and Robinson, and Thackeray’s Becky Sharp and Rawdon living in Mayfair on nothing. It seems the predominant Victorian story was not how wonderful it is to live luxuriously through credit—one which today perhaps underlies in an unacknowledged way magazine advertisements and popular Hollywood movies.

In the discussion period afterwards I mentioned those businessmen in Trollope who do end up well and contribute to the community (there are a couple, e.g., the exemplary civil engineer, Theodore Burton in The Claverings), and his Roger Scatcherd who ends up a self-destructive alcoholic because his class origins isolate him after he has made enormous sums building railroads. Edith Wharton’s Custom of the Country was mentioned as a rare novel where a pair of people end up rich and successful as a result of utter amoral ruthlessness and destruction of others on the way up.

Perhaps one of the three interesting paper for me (the other two were one in a session on Scots literature and another on radio plays—which I’ll write about in further letters), one of the three, I say, in the whole MLA session was the first in an early Friday morning session (8:30 am): “The Body as Boundary in Victorian Culture and Medicine.” In “Poverty Embodied: Spectral Intrusion & Narratives of Class in Victoirian melodramas,” Heidi J. Holder discussed a subgenre of Victorian melodrama which combined ghost with realistic stories. Her texts were Wilkins’s Money & Misery, which included an adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell’s “Old Nurse’s Tale”; Young’s Jessie Ashton which combined domestic melodrama with a ghost apparition, & an anonymous play, Rats Whirlwind which was never permitted to be staged, not because it was more lurid, or more revealing of violence, hatred, and self-destruction within families, or class-rooted miseries, but because such material was part of the so-called realistic story and not contained (kept apart) in the supernatural part of the drama.

Ms Holder retold the stories of these melodramas in detail: Money & Misery turned Gaskell’s wintry ghost story, which centered on a young woman who had a child by a man she was forbidden to marry, into a story about her vicious father and his unknown poor son who lives a hovel nearby & is transported one Xmas, but who by the end of the drama regains his rightful inheritance. In Money & Misery the illegitimate child dies in the snow; in Gaskell’s story she is rescued. Jessie Ashton is about a beautiful poor women who kills people and hides their corpses; the apparitions in this story are intended to show that benign justice exists in the supernatural realm. All three dramas contain scary stories of the powerless devastated, yet rewarded for resisting collapse into viciousness. Survivors generally shift their class allegiance and identity away from poverty; helpless lower class women generally end up dead. In Rats Whirlwind, the parents beat and starve a child to death, the husband assaults his wife, all is paranoia without a sign of providential patterning.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1902), snow scene (Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes, 1872)

The 2nd & 3rd papers might be said to be about fears of sickness. Like Holder’s paper, Ross Geoffrey Foreman’s “A Parasite for Sore Eyes: Rereading Infection Metaphors in Bram Stokers’ Dracula” concentrated on how under the veil of the supernatural social troubles and sexual anxieties could be depicted. Foreman argued that beyond syphilis, and archetypal ideas about blood, Dracula presents ideas and experiences of malaria, and can be read in the post-colonial fashion as a text connected to British fears about the results of their empire-building. Pamela Gilbert’s “Victorian Skin & Bathing was about how Victorian people had become aware of how porous and dangerous is skin (people have a lot of it), and how commercial establishments were set up for men for bathing where manliness was equated with cleanliness, sea-bathing, preventive measures against illness; poor men were encouraged to think cold water bathing was good for them. She mentioned the increase in Turkish Baths (although she did not cite it, Trollope has a story called “The Turkish Bath”). The Australian satirist and socialist Furley made fun of the underlying class and race prejudice that could be found in all this matter.

In the discussion session afterwards I asked Ms Holder if other Victorian melodramas took an original story which was told from a woman’s point of view and centered on women characters and transformed it into Oedipal tales about men. It’s been my finding that repeatedly film adaptations turn novels which center on women into Oedipal stories (e.g., Hitchcock out of DuMaurier’s fiction). She resisted this political or feminist perspective by saying there were many women in Victorian melodrama. I asked Ms Gilbert if advertisements about keeping the skin clean and the danger of bodily fluids were directed at women (after all women have plenty of bodily fluids seeping out), and she said yes, but that she concentrated on men because she was interested in the redefinition of masculinity implicit in the ads.

At noon, the 2nd of the “Mid-Victorian Self-Assessment” sessions was held: “Victorians between Past and Future.” Nathan Henley read The Mill on the Floss as a parable about the emergence of a modern society founded on justice & law from a pre-modern community founded on brute force and prejudiced cruel ideas. The question Eliot asks is, is the modern world a rational one? Wakem is the modern capitalist, who (as we know) loses Maggie who dies. He seemed to suggest the novel is conservative and melancholy. In “Structures of Regret: Promoting Strategic Investment in the Mid-Victorian Novel,” Rebecca Stern again used little-known paintings and illustrations, this time to discuss financiers who committed suicide; a common theme in these pictures and novels is about life’s (other) opportunities missed, & unproductive regret. Katherine McCormack showed that George Eliot’s narrator in her novels before she allowed her public to know she was a woman writer was characterized and described so as to give the impression the writer of her books was a man. She dropped all such masks, but instead of emphasizing her gender, presented her narrator as a world-travller, nostalgic, and writing at a distance from her fiction.

In the discussion afterwards one man got up and said he had invented the topic for this session because he had hoped to hear about (what he thought was a common) optimism in Victorian texts about the future. The speakers defended their papers on the grounds their readings of their materials were accurate, which it seems to me these were. I didn’t have the nerve to raise my hand: there were so many people at this session. But I can here in this letter say that had the speakers chosen another genre to discuss, say travel writings, or political and scientific tracts, they might have found much optimism in Victorian texts about the future: Trollope’s travel books are rife with hope, looking for improvement through industrialism, immigration, modern values, while his novels are often melancholy.

The last Victorian session I went to on these two first two days was “The Material of Devotion: Books, Bodies, and Victorian Women’s Religious Poetry” (3:30 pm). Cheri Lin Larsen Hoeckley spoke about Adelaide Proctor’s use of devotional sentimental poetry to focus on poverty, exile, homelessness, female communities; Proctor used the profit she made from Chaplet of Verses to benefit women. Proctor saw women’s lives were a target for exploitation, & she attacked the way respectability became a way of excluding women from social help ruthlessly. Stephanie Johnson’s paper was on Alice Meynell’s poetry; Meynell was said to look upon her poems as her children, to connect women’s poetry to domesticity, to regard poems as creating an order of beauty (reflecting the “divine” world?). Johnson rehearsed ideals she found in Meynell’s life, which she connected tto Meynell’s poetry. The last paper, by Krista Lysack, was on Christina Rossetti; Lysack’s purpose was to emphasize the religious ideas in Rossetti’s poetry, her use of sequences to structure her poems, and tell her audience how Rossetti’s poetry sold very well in her era.

Although I like 19th century English women’s poetry, and am very fond of Meynell’s writing, I found this last session a little disappointing. It seemed that having religion at the center of the session made everyone very solemn, and there was little discussion of less high-minded motives, except to show that this sort of poetry was popular or made money.

I have discussed Victorian women’s poetry on this blog before, and told of how I came to be very fond of Alice Meynell (by luckily coming upon books of her prose essays and biographies in used bookshops). However, I find I have never put a poem by Meynell or Proctor here before. It seems fitting to end on one each.

Here is the opening of one of Meynell’s long blank verse poems:

A Study: In three monologues, with interruptions

I

Before Light

Among the first to wake. What wakes with me?

A blind wind and a few birds and a star.

With tremor of darkened flowers and whisper of birds,

Oh, with a tremor, with a tremor of heart

Begins the day i’ the dark. I, newly waked,

Grope backwards for my dreams, thinking to slide

Back unawares to dreams, in vain, in vain.

There is sorrow for me in this day,

It watched me from afar the livelong night,

And now draws near, but has not touched me yet.

In from my garden flits the secret wind

My garden—This great day with all its hours

(Its hours, my soul!) will be like other days

Among my flowers. The morning will awake,

Like to the lonely waking of a child …

One of those handed out on a xeroxed sheet in the session and then discussed:

To the Body

Thou inmost, ultimate

Council of judgement, palace of decrees,

Where the high sense hold their spiritual state,

Sued by earth’s embassies,

And sign, approve, accept, conceive, create;

Create—thy senses close

With the world’s pleas. The random odours reach

Their sweetness in the place of thy repose,

Upon thy tongue the peach,

And in thy nostrils breathes the breathing rose.

To thee, secluded one,

The dark vibrations of the sightless skies,

The lovely inexplicit colours, run;

The light gropes for those eyes.

O thou august! thou doest command the sun.

Music, all dumb, hath trod

Into thine ear her one effectual way;

And fire and cold approach to gain thy nod,

Where thou call’st up the day,

Where thou awaitest the appeal of God.

And from Adelaide Proctor’s Chaplet of Verses,

Homeless

IT is cold dark midnight, yet listen

To that patter of tiny feet!

Is it one of your dogs, fair lady,

Who whines in the bleak cold street

Is it one of your silken spaniels

Shut out in the snow and the sleet?

My dogs sleep warm in their baskets,

Safe from the darkness and snow;

All the beasts in our Christian England,

Find pity wherever they go

(Those are only the homeless children

Who are wandering to and fro.)

Look out in the gusty darkness

I have seen it again and again,

That shadow, that flits so slowly

Up and down past the window pane

It is surely some criminal lurking

Out there in the frozen rain?

Nay, our Criminals all are sheltered,

They are pitied and taught and fed:

That is only a sister-woman

Who has got neither food nor bed

And the Night cries ‘sin to be living’,

And the River cries ‘sin to be dead’.

Look out at that farthest corner

Where the wall stands blank and bare:

Can that be a pack which a Pedlar

Has left and forgotten there?

His goods lying out unsheltered

Will be spoilt by the damp night air.

Nay;—goods in our thrifty England

Are not left to lie and grow rotten,

For each man knows the market value

Of silk or woollen or cotton . . .

But in counting the riches of

England I think our Poor are forgotten.

Our Beasts and our Thieves and our Chattels

Have weight for good or for ill;

But the Poor are only His image,

His presence, His word, His will

And so Lazarus lies at our doorstep

And Dives neglects him still

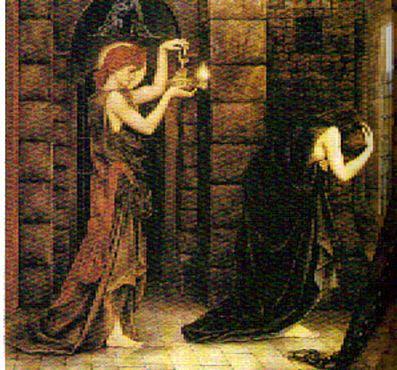

Evelyn de Morgan (1855-1919), Hope in the Prison of Despair (1887)

In my next letter I’ll describe the Victorian session I went to on Sunday and related sessions on Virginia Woolf (Thursday) and Scots Literature (Friday).

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- A little more on the question of how supernatural gothic was used in Victorian melodrama:

I have to say to say there are so many women in Victorian melodrama is to ignore the content of my question. Ms Holder emphasized in her talk how class differences are so central to the way people are presented and treated, and how class identity infects all the melodramas; she did go into (but much less) of sexuality, internecine conflicts in families in a capitalist system which punishes anyone and any family who didn’t kowtow to harsh work ethic (long hours, hard labor) and submit to very low wages, no security, little access to health care (in Mary Barton Gaskell shows how in order to get into a hospital the average worker had to have the rich family of the factory contact the hospital administration and ask first). These conflicts are also in the plays clearly not only about money and sex, but about power and come out of the same kind of cruelities that produced self- and socially-induced bodily mutilation and harm. But not only were the victims and villains in her chosen plays (and those she generalized about) generally poor women, the heroes and those who were shown to be powerful, good, earning a place in society, were apparently all men. And this from matter which had centered on women’s stories from a woman-centered point of view.

She did have an important point: the supernatural terrain allowed Victorian writers to write of all these things. Rats Whirlwind was banned forever because this matter was put into the realistic section of the play and there was no benign divine design justifying all and no happy ending for anyone. We can see in 19th century and more modern gothics by women how the supernatural allows them to present life from a woman’s point of view far more frankly than they can in her realistic fiction.

The popular films and TV shows (where the writers are overwhelmingly men) adapted from texts written by women from a feminist & from a woman-centered point of view where the story becomes one about a man transformed, rising in an Oedipal pattern in just the manner of Money & Misery include all Andrew Davies's film adaptations of classic and high status books.

E.M.

— Elinor Jan 11, 8:05am # - Thanks for posting fascinating notes above, Ellen. I’ve been looking forward to hearing about the sessions ever since you went. We have two beaches locally that were used in Victorian times. One was for men and older boys, the other for women & younger children of both sexes. It’s always put down to Victorian prudity, but I wonder if there was some link to the Victorian’s belief in the dangerousness of porous skin. Probably not but these things are often more complex than seems superficially. Anyway, thanks for taking the time, I really enjoyed reading about the sessions.

— Clare Shepherd Jan 11, 5:26pm # - From Patricia:

‘Hi Ellen,

being up at this appalling time I only want to say Brava as usual for your provocative and searching comments on the MLA conference you attended re the session on the 3 Victorian women poets.

Absolutley right on , Ellen. Why do today’s women scholars (poets too??) make such a wide berth around erotic, even domestic in looking at earlier women writers.

I love your commentary. Amazing how much you do, take in, analyze, deliver.

Much best,

Patricia B.”

— Elinor Jan 12, 6:29am # - Dear Clare,

That's very perceptive of you -- as I said so little. Gilbert began her paper with a effective description of skin and how it’s the individual’s interface with everything else and how necessary for individuals is adequate space around their body. She emphasized the body itself is dangerous; she cited an essay by Bourdieu where he suggested that good manners makes us keep our bodies closed to others. All abject products of the body and skin are kept from public view.

In the 1840s Victorian people became aware of the skin as dangerous and porous. Many publications emerged in that decade. (Why? I don’t know.) Among these may be seen a new emphasis on bathing as medicinal, on preventive maintenance of the body. Some of this was class-linked: the middle class fearing catching disease from working class people and also thinking themselves superior (becuase they could afford to have clean clothes and linens easily).

She did say that women were central in the new ethic of bodily cleanliness, but did not tell anything of the nature of the propaganda (we can call it).

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 12, 9:38am # - Dear Patricia,

In general most sessions I attended had scholars giving papers which did not include political interpretations of what they were presenting. Most people avoided any whiff of feminism. It seems with the death of deconstructionism (which did bring in terrible jargon, partly to hide what was said lest it offend or seem subjective), this is a way to protect your career.

A particular facet of what is avoided in the case of women is talk about their sexuality—probably what was so revolutionary about Clarissa and grabbed me at age 18 and still engages me deeply today is the frank presentation of sexuality as a target or site for exploitation and power relations. Emma Donoghue’s Slammerkin more frivolously laid open the same area; a recent masterpiece centering on women’s sexuality frankly is Rosamond Lehmann’s The Echoing Grove (and I recommend her The Weather in the Streets for a still highly unusual frank depiction of pregnancy & abortion.)

Women are still afraid to tell. They fear they will be punished somehow somewhere and they may often be right. In my foremother poet posting this week I put a typically highly erotic poem by Christina Rossetti where she is longing for a man (or death), the kind still popular, and another where we see some of the pernicious self-destructive repressive attitudes she had towards sexuality. What other 19th century women poets did was write sentimentally about these things but they did frankly write about them -- and not to glorify or glide over painful results in social life.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 12, 9:43am #

commenting closed for this article