Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Scots Literature, Radio Adaptations, Digital Turns, Borat & Hotels, MLA 2007 · 16 January 08

Dear Harriet,

Here is my last report on the MLA Conference. I have two excellent, & a couple of interesting sessions to tell about—as well as one I thought revealed our increasingly vicious popular public media.

The wholly worthwhile sessions first. The chair, John Corbett, of “Scottish Literature and The Union” (Friday, 10:15 am) said this was but the 3rd years there’d been any sessions devoted sheerly to Scots literature, and this was the 1st of 7 (or maybe 9!) sessions at the MLA devoted to Scots literature. I had chosen it from the others (I did notice a couple which had attractive titles) because 2 of the papers were on 18th century literature, & a 3rd on 19th into 20th century so I could hope I would recognize some of the writers. Maureen McDougall Martin discussed the imagery used to describe Scotland in propaganda promoting the union of Scotland & England, and teased from this imagery an image of masculinity based on primitive culture that came to be associated with Scotland. She ended with Walter Scott’s novels (particularly Redgauntlet) which have emphatic elements of homoeroticism, a romantic primitivism connected to the Highlands, and wild noble nationalism. Rivka Swenson also discussed how early on Scotland was presented as a woman, women writers (like Susan Ferrier in Marriage whose travel to England stimulated her into becoming a partly Scots writer).

Robert Cairns Crag’s “Forging Literary Traditions” was fun to listen to. He challenged 2 conceptions: 1) he said the Scottish enlightenment was Scottish (not Anglo) through & through; and 2) far from being coopted & subdued by English influence in the 19th century, many Scots writers dominated the English scene. He instanced Hugh Blair, Burns, Carlyle, Robert Louis Stevenson, the quarterlies in Edinburgh. He argued Hugh MacDiarmid’s idea that Scots literature died sometime after Dunbar was nonsense; it was due to 19th century editors that we know Dunbar. His iconoclastic view was delivered with wit and aplomb.

The chair remarked on “a forest of hands” when it came to the question period. I got two in. I asked Ms Martin about the film, Rob Roy where we also have a powerful woman presented (Helen, Rob Roy’s wife). I also asked about Blackwoods (which Prof Craig said set a central agenda for 19th century culture) and Margaret Oliphant as an unestimated Scots writer. Later on (after I had gone to a couple of dull sessions, which I described under “The Victorian Age” and “Women writers”), I regretted not going to more Scots sessions (one had a great title, “Ghostly National Imaginings: Scotland in the 19th Century”); this one was was filled with the enthusiasm of a growing area. Next year Jim says we’ll go to San Francisco for the whole of Winter Solstice season (the way we went to Paris some 7 years ago now) and I’ll be sure and go to far more of these Scots sessions. The chair, John Corbett, was giving way copies of The Scottish Review of Books, & he said if you went to the Scottish table in the book marketplace you could get a free book. And sure enough I did: a beautiful edition of Margaret Oliphant’s Beleaguered City and other ghost stories, and a free useful-sized dark blue cloth tot bag (which says “scottish writing” in white letters).

Liam Neeson & Jessica Lange as Rob Roy and Helen MacGregor in Rob Roy (1995)

The other session I found absorbing was on radio adaptations partly because I am studying film adaptations, but partly simply because the matters chosen and points of view were stimulating. The title of Daniel H. Foster’s paper, “I See A Voice” hid what was its fascinating matter. He discussed & had a tape of Orson Welles’s notorious War of the Worlds radio broadcast, some of which Foster played. He showed how Welles used narrators and disembodied voices (each of which disappeared one by one) and ingenious imitative sounds to terrify his audience. There was no framing to the story: he narrators addressed the audience directly as “you.” He also argued that people tend to credit what seems to be a documentary strongly. Gerard McGowan’s subject was the use of gothic (from Poe) and subversive material (Melville’s Billy Budd) to speak to concerns of people at home during WW2 and to show fighters as peacemakers. The programs attempted to reassure people the return of a man who has seen and been killing for years need not perpetuate violence. The subtexts and unacknowledged subtexts of these radio broadcasts, plus how they sound juxtaposed to cigarette ads (with their myths of masculinity and social consolation) is relevant to our present incessantly militarist and wartime era.

Orson Welles at the Mercury Theatre

I found the last paper, Jeff Porter’s “Against Adaptation: Beckett and the BBC,” filled with information that substantiated what I have read about what happened to BBC drama in TV in the following decades. In the early years of both media the BBC had many writers and high ideals; the latter included a desire to see original drama created for these new media. Beckett wrote All that Fall for radio; that is, he wrote a play which experimented with sound properties (it includes a bunch of savvy meaningful acoustics). It’s the story of a heavy woman who while walking down a road to meet her husband at the station encounters adventures and people. Beckett forbid this play to be adapted to the stage as he forbid his stage plays to be changed when put on film or TV. Porter said the status of radio soared in the 1950s and 60s (a highpoint was Under Milkwood, 1954).

Much more mixed were the two digital sessions I went to. On Friday (8:30 am) Jim and I went to “Got ECCO.” Six people spoke for 10 minutes each on how the existence of ECCO has changed the way scholars can and do study the 18th century; they spoke of the high price asked for this digitalization of the old microfilm collections which does not include any new editorial matter. Spending money this way precludes spending it in others. Although some deplored the lack of any evaluative tools, all agreed that any one not having access to ECCO is now at a real disadvantage. The college I teach at does not have ECCO. Someone said the collection ought to use tags, only what tags to use was not clear. This reminded me of Jim and my failure to make our catalogue at Library Thing useful to us: only after we had catalogued most of our books did it become clear what tags we should have used1.

I should say I used the collection in the 1970s at the NYPL on 5th Avenue (NYC) & in the 1980s at the Library of Congress: to locate the microfilms you had to go through cumbersome looseleafs where the microfilms were not alphabetized by the name of the author or title of the work, but instead numbered in accordance with the date the microfilm was made, not its chronological place in the 18th century. I think but am not sure these microfilms are still available at the libraries that used to have them. The microfilms were hard to find and not fun to read on machines, but I was able to xerox aquite a few books I needed or wanted to read, & at the time felt extraordinarily lucky to be able to reach rare fiction and poetry by women writers from Charlotte Smith to Oliphant. I still have these xeroxes in folders in my workroom. Between digital texts on the Net in public and small feminist and cultural studies type university presses today many of the texts I got this way are readily available to anyone who has a credit card or access to the Net.

(1828-1897)

The speakers at the other digital session were scholars who blog or put their published work on personal websites. Each had a word to meditate: Miriam Burstein spoke on the problems & temptations of bloggers writing in “public;” Kathleen Fitzpatrick talked about how the profession could decrease the quick “obsolescence” of some of their work (say reviews) if they could bypass the long-drawn out processes of peer-review in academic journals; Lisa Nakamura showed how “race” prejudice and stigmatizing is found on the Net as much as it is in physical space, only its manifestations (symbols) are different. I thought the best parts of this session were suggestions of how to make bloggers more respected, how to somehow integrate websites with traditional academically respectable venues and candid comments about what is valued and useful in literary study.

The chair of the last session I’ll tell about, “Reeling with Laughter: Humor on the Silver Screen” (10:15 am, Saturday) revealed she was aware one could have a very different attitude towards the content of modern humorous shows today than the one she apparently holds: she repeated several times pointedly how this session was for people with a sense of humor. This kind of statement is a way of shaming those who are hurt from justly pointing out where the cruelty or prejudice lies in the joke. Heidi Moore’s paper on Christopher Guest’s “mockumentaries” was in fact innocuous: she played bits of Guest’s movies to show how he parodies documentaries gently. Vincent Casaregola discussed parodies of films which do homage to the previous film. He said such films are wrongly characterized as pastiche films. They are intertextual. He made a number of interesting observations as he went over his chosen films, e.g., in Christmas films the desire to commit suicide is a common motif.

A journalist, Dave Soldana’s paper on the movie and TV show, Borat caused understandable upset in more than one person in the audience. While Soldana seemed at first to acknowledge the sadism and playing to anti-semitism, hatred of women, race prejudice and the rest that makes up the matter of Borat’s jokes, this was part of a strawman approach: he conceded this truth in order to justify these programs as documentaries exposing the actual values of their audience by expedient exaggeration. He also chose people who have argued “Borat is not and cannot be funny” if you are X (a woman, a black, &c) who he thought he could make fun of: e.g., Gail Dines who made the error of saying “all women” feel rage. True, she should have said “some.” I’m not sure his argument was in good faith, as he described sitting amid an audience in Iowa enjoying the humor and (he opined) learning from them. By this he meant all white audiences. What if he had sat in an audience of all black people Harlem. In fact one of the women who questioned him was black, and it was clear that if not all black people feel distressed when they watch Borat, she did. His way of justifying the humor of this show to her was to name some TV shows which are egregiously racist. This seemed to me a very low standard by which to measure other shows.

I did not raise my hand to try to make any comments during this session, but instead watched as if I were an outsider. One young man got up and said “what a great age” we live in having this type of humor available to us. Others rejoiced over mock news, reality shows & contests. So I cannot say all the people watching this show are conscious they are enjoying ugly forms of triumph, whether over those mocked or over the mocker. Some may get a kick out of identifying with stupidity and cruelty as a kind of rebellion against daily ordinary norms of kindness and good taste.

What bothers me is such a show (and also reality shows) make unkindness, bad taste, & bullying socially acceptable. They are 21st century equivalents of freak shows, only instead of using physically disformed they use emotionally vulnerable people.

That’s not quite all for this year’s MLA, Harriet. The convention hotels were huge, & for the first time we stayed in a glamorous hotel filled with thousands (it seemed) of people. It had 35 floors, two fat towers, underneath the ground 7 different levels each with its own colored decor—I’d get lost periodically but there were so many employees about there to help people. Revealingly when we first arrived, he just hated the look of the hotel, was very irritated because he thought what he had bought would not be available. It was: we were in an area of this huge place where a breakfast, coffee at noon, and snacks and wine were available in a kind of indoor terrace place connected to those in this area. He did go a gym there—naturally there was an extraordinary gym in this labyrinthine place. The management nickel and dimed the customers (or I should say $5 & $10 dollared them for refreshments at every turn). We did at one point take a cab deep into a poor area of Chicago and I saw long stretches of grim streets. Twice I lost one of my notebooks & twice Jim retrieved it from where I had in my fluster left it; I did lose a nice hat—and Chicago is cold so losing my hat was ridiculous. My worst moment: I was snubbed by someone from where I work. Best moments: talking with other Victorianists before and after sessions.

Jim & I seem to be doing things conventional careerist types do at age 35, but then couldn’t do this sort of thing then & we aren’t doing it to build any careers now; we hadn’t the money, knowhow, & had a small child then; I have just as strong a sense of the meaninglessness and irony of self-importance now.

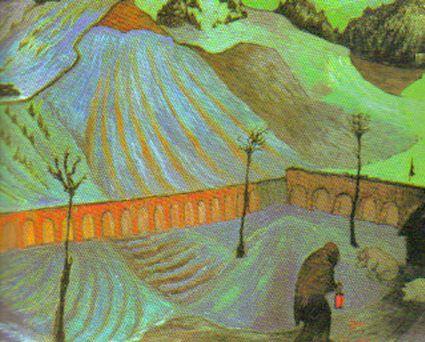

Marianne Von Werefkin (1860-1938), Woman with a Lantern

The woman with the lantern is me. I make these notes so as to try to make going to these conferences useful to me. The reports help me remember what was said.

Sylvia

1 The search engine is awful.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Thanks for that Ellen. I loved your account of the Scottish sessions. I found them both extremely interesting.I bought a complete set of Scott some time ago. I’d love to read more than Ivanhoe & Rob Roy, the only 2 I’ve read so far.

— Clare Shepherd Jan 17, 2:53pm #

commenting closed for this article