Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECS, Portland: Women's writing & landscape art · 3 April 08

Dear Harriet,

The subject matter of my second report on the ASECS sessions at the Hilton Hotel in Portland, Oregon is women’s writing, with a little on landscape art. I heard a large number of excellent papers on women’s texts and went to one visually attractive power-point talk.

This time I won’t go in chronological order, but rather begin with the sessions and papers I most enjoyed and took most notes about: on Friday morning, “Women and Nature,” about landscape, reformers, and letters; and “Pregnancy and Childbirth in Eighteenth-Century Fiction and Society;” on Saturday morning, “Agony Aunts and Confidants in Burney and her Circle,” which included a paper on Jane Austen’s novels. Then I’ll end on two individual papers, one of which I also liked very much, from a session on “Obscurity,” Antoinette Sol’s paper on Elisabeth de Faverolles-Guenard, baronne de Mere.

When I arrived at 8:00 for “Women and Nature,” I was delighted to recognize in Janet R. White a woman who I had heard give an excellent paper in the ACESC at Montreal (two years ago) on how Marie Antoinette’s gardens, landscape and houses mirrored an image of herself as a queen of love, charm, pastoralism, quiet virtue, retreat and playfulness she wanted others to have of her. Ms White gave another paper on landscapes: this time she showed that the “jardin anglais” of three different French male aristocrats also reflected the image of themselves they wanted to project to their communities. Unlike English gardens of the era which really grew out of having large country estates, the wealthy French bought small grounds near Paris, sold tickets to them. Two of the males she discussed (Monville whose mistress was Du Barry, and the king’s brother, Artois) projected the image of a libertine, building erotic allegories in hermitages, temples, tomb houses, bridges, grottos, crags, and river gorges.

Monville’s Temple to Pan

A third, D’Ermenonville, a man interested in philosophy, Rousseau, who also had to take some income from his land, built into his landscape into a temple to modern philosophy and usefulness, with working farms, where botany was practiced.

View of Parc D’Ermonville

Once again she showed how Marie Antoinette’s gardens had temples of love, stage sets for her to have plays done and be a milkmaid (12 peasant families were put into one large house); playful folly and the beautiful, the home-y too as ideals are found everywhere, nowhere the wild, dark or mysterious:

Gardens of the Petit Trianon

Again as in Montreal, Nicolle Jordan was on the same panel as Ms White. Then Ms Jordan discussed one of Mary Wortley Montagu’s Horatian epistles; this time she discussed Elizabeth Montagu’s letters. Mrs Jordan showed that Montague used the imagery of pastoral and a pose of herself as a sheperdess in retreat in the early part of her life, but as the years went back and she married and worked alongside her wealthy industrialist husband, she began to use imagery drawn from georgic poetry to justify her way of life and activities. Elizabeth Montagu played roles in her letters to position and present herself as a woman using her wealth, power (and luck) worthily. As a woman she was in need of reassurance and acceptance. Ms Jordan quoted some lively and self-conscious passage from the letters, described Montagu’s correspondents, and situated the letters in the poetry of the era and Montagu’s personal life.

The young Elizabeth Montagu, as a shepherdess by Frances Reynolds, engraved by C. Townley

Ms Jordan is apparently working on a book on the poetry of Anne Finch and Mary Wortley Montagu (two of my favorite 18th century poets, who I’ve done much work on too). During the talk afterwards a woman in the audience was sceptical about taking figures from poetry to explain letters. (She spoke low so I couldn’t quite hear what she said.) So I spoke up to tell Ms Jordan of how Veronica Gambara used the figure of a shepherdess and the norms of pastoral poetry to present herself as far humbler and unworldly than she was, but also to justify her desire for retreat, and how in general Renaissance women did use figures from poetry in their letters. This was common. In the 17th century these groups of images and types are found in flattering paintings of upper class women.

The last paper of this session was by Judith Slagle who has edited and published the letters of Joanna Baillie. Ms Slagle told of how James Montgomerie and a group of well-meaning Scots poets and establishment people published a book meant to be part of an effort to end the hideous exploitation of young boys in the chimney sweep trade. Montgomerie asked Baillie and Walter Scott to contribute moving poems. Both Baillie and Scott felt sentimental poems would have no effect at all: Baillie wrote an informative and eloquent paper on how chimneys of the past had been built so that chimney sweeping was done by two adult male bricklayers, one standing at the bottom and the other at the top, and together managing to use brooms and other implements. Baillie argued laws needed to be passed to stop the building of chimneys that became crooked. Scott also contributed a prose argument. Ms Slagle then went through the sorry history of anti-chimney sweep legislation, none of which was given any effectiveness (through putting in punishments for those who disobeyed) until late in the Victorian period. The years of different laws may be looked up on the Net; I didn’t know that soot was sold as a profitable fertilizer nor that what we really know in intimate detail of the practice comes from the defatigible decent humane man Henry Matthews. Ms Slagle also told of how in Baillie’s later Victorian phrase she became a reformer, and worked for progressive women’s causes. As two Fridays ago I put on Wompo a foremother posting about Joanne Baillie which included three of her poems and a short life, I’ll put it on this blog tomorrow as an addendum to this letter.

Mary Trouille was the chair for the superb panel on pregnancy and childbirth, as last year she had been the chair for a panel on “weddings nights” in 18th century fiction. We discovered last year how little has been written down about the realities of wedding nights in non-fiction and fiction too. It seems to be a verboten area, where people are determined to keep this area of life hidden supposedly so it may remain romantic and idealized. Not so pregnancy and childbirth, which have at least been written extensively about and by women too in non-fiction treatises and private letters.

Two of the papers drew upon treatises, and two upon letters and literary texts. Deborah Nestor’s outlined how orgasm which had in the Renaissance been thought necessary for conception began in the 18th century to be thought medically undesirable. Nicolas Colepepper’s 17th century treatise was a foundational text about physiology with which Jane Sharp agreed. As described to me these treatises show many adversarial attitudes towards women and little understanding of post-partum depression, the emotional needs of women (much less sickness and infection); their aim seems to be to control women, to allow them sex only insofar as it serves the purpose of the male to have children.

Pam Lieske summarized the contents of midwifery treatises by Elizabeth Nihell (1760) and Matha Mears (1797). Nihell vehemently opposed the increasing number of men working as midwives or obstetricians, and their use of instruments; she tells of women mentoring and training other women, and insisted this was a realm women understood best by instinct. Her life history is sad: she was trained in Paris in 1747 (Hotel Dieu) and lived in London by 1754. In 1771 her husband deserted her; by 1775 she lived in a workhouse and she died a pauper. Martha Mears wasn’t learned, & still shows a real knowledge of anatomy, and presents specific criticisms (for example, the manual removal of the placenta). She wants to see people take preventative measures to help women, writes of a clinic opened in 1739, and argues that pregnancy should not be seen as an illness. The ideals of sensibility influenced Mears: she advises the pregnant women to avoid strenuous exercises, go out for walks in nature, and on the care of children. She vehemently opposes all forms of abortion (using the word in the modern common popular sense).

Madame Roland’s powerful memoir, first published in the 1790s after her death

Since I knew much of the matter in Anne Smart’s paper on Marie-Jeanne (Manon) Phlippon Roland’s letters, I was listening to see what was the attitude towards Roland’s obsessive determination to breast-feed her child after childbirth when she found she had no milk. Ms Smart saw Roland’s behavior as a way of gaining agency over her body, not as obedience to Rousseau norms. Roland was much involved in her husband’s political life, helped him publish his learned treatises. She educated herself thoroughly in the area of obstetrics through reading and carefully observing and writing down the changes in her own body. In some advice to her daughter, Roland blamed men for some of the problems pregnant women experienced. Roland was challenging male doctors’ control. Ms Smart quoted Dena Goodman’s idea that by writing letters women constructed a self and staged a life, asserted autonomy.

Mid-19th century study of Roland, includes many letters, made possible by her daughter

The fourth paper, by Holly Waddell, was about the image of Medea. Ms Waddell began by retelling Corneille’s Medea, went over how frequently the story was retold or alluded to from the later 17th through 18th centuries. She argued that not only anxiety over infanticide lies behind the figure, but a justification for bloodletting as necessary to build and alter a state. Medea frees herself and is a sublime tale of about liberty and thus connects to the female figure of liberty.

I admit to disappointment and a sense of disquiet. For example, nowhere did Ms Smart question the recent orthodoxy about breast-feeding nor did anyone else on the panel question any other orthodoxies about required behaviors for mothers or motherhood as justly all-consuming experience for women. Other current medical orthodoxies (about hormonal imbalance as very bad for women) and women’s sexuality were left unexamined. The admiration for Medea was not criticized; I am troubled by the general argument one must have violence to secure a stable order. Who is to do this violence? against whom? (See my review of a book which accepted

this argument.) So I was relieved when Ms Trouille made a joke about how ironic it was that Roland was disappointed in her daughter who grew up to be nothing like her mother intellectually. Had Roland gone to all this effort to no avail? The magic didn’t work it seems.

Perhaps the session I most enjoyed of the whole conference was under the auspices of the Burney Society on Saturday morning: on agony aunts and confidants. Margaret Anne Doody gave a superb and perceptive paper on the relationship of Frances Burney and Hester Thrale. Ms Doody said much at great speed; what I liked best was how she conveyed the nuances of an ambivalent yet deeply intimate necessary and supportive relationship the two women built and maintained until Hester Thrale decided not to repress her desire for deep happiness and to marry Gabriel Piozzi. Ms Doody connected her quotations from their letters to Burney’s novels, and among other things said what a nervous sycophant was Charles Burney, how the Delvilles in Cecilia represent Burney’s take on the Thrales, why Fanny turned on her friend and Fanny’s vexed relationship with George Owen Cambridge, how Hester Piozzi never gossiped about Fanny Burney D’Arblay, how hard it was for women to form and maintain friendships, and how intimacy and sharing secrets can form an intolerable burden.

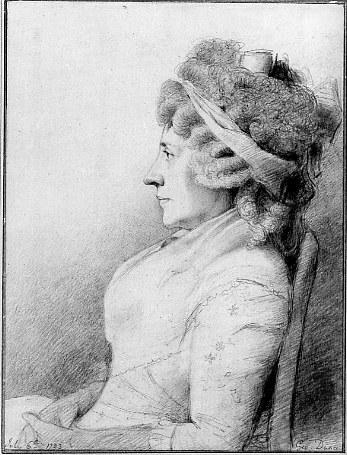

Hester Piozzi by George Dance, 1793

Joanne Holland also talked about non-fiction letters: Ms Holland’s paper was on Mary Delany and she went over this woman’s often hard life (the early forced marriage to an aging alcoholic), Delany’s happy years in Ireland, her later need of women patrons and how this affected Delany’s behavior, and finally, and how she became a surrogate grandmother to Burney who (alas) contributed to placing Burney at court for a hellish five years during which time Delany (when alive) helped Burney very little. Holland justified Burney: she could not help Burney much for to do so would risk her own favor with the queen. This was another story of two women who needed one another and attempted to live up to ethical and emotional ideals, but who found circumstances & social norms & enforced relationships with other powerful people in the ened prevented the intimacy and helpful relationship from continuing as thewomen ideally wanted it too.

Mary Delany in old age by John Opie (Amelia Opie’s husband—see below for Amelia Opie’s poetry)

The other two papers were on fiction. Lori H. Zerne showed how the function of chaperones supposed to be advisors to young girl actually worked out in life as reflected in Burney’s fiction. She alluded to Ruth Perry’s chapter on aunts and chaperons in her book, and then outlined the duties of the chaperon as guardian, mentor, and matchmaker. Revealingly the women who enacted the most male and less socially acceptable behavior of all the chaperons in Burney’s fiction, Mrs Selwyn, is the woman who succeeds best in doing these three duties; she protects and helps her charge to what she needs and wants. Mrs Mirvan, Madame Duval, and others are often worse than useless. Ms Zerne felt Burney’s novels found a place for dissent from orthodoxies about feminity and who makes a good husband by showing the inefficacy of exemplary feminine and transgressive chaperons and how they are treated (Madame Duval miserably).

Fanny Burney in a tremendous hat by her cousin, Edward Burney, 1784

I really enjoyed Linda Zionowski’s paper on chaperons in Austen’s fiction. She began with the ways the heroines in Karen Fowler’s The Jane Austen Book Club turn to Austen’s novels for impeccable advice. The implication is fans of Austen use her books as women were once supposed to use chaperons: Austen’s books are supposed to contain wonderful advice about life. Instead she showed that Austen’s books continually show the ineptitude, incompetence, and indifference of various aunts, mothers, and chaperons. When we do see an aunt who gives good advice (Mrs Gardiner), it is not heeded, and the narrator remarks how wonderful it was that the recipient (Elizabeth) did not resent being advised. We see in much of Austen a systemic failure in chaperons and advice (e.g., Emma Woodhouse to Harriet Smith). The unpredictable erotics of friendship itself often makes advice skewed. The most radical stance towards advice is found in Persuasion where Lady Russell comes near to ruining Anne Elliot’s life.

Sylvestre Le Tousel as Mrs Allen, leading her charge, Catherine Morland (Felicity Jones) in a shopping expedition, from the 2007 Northanger Abbey film

The discussion afterwards was lively. One woman raised her hand to object to the whole sceptical trend of all four papers. She was (alas) put down. Spmeone said how poignant it was that relationships between women couldn’t come near ideals. Women lacked social authority. Two of the women endured horrible marriages (Thrale and Delany); they were all dominated by new forms of capitalism making new demands. I mentioned that in general the Austen movies try to show women’s friendships as working beautifully; they try to emphasize the good women who give advice (as in the 79 P&P Mrs Gardiner’s role is extended), but that books by women in the movies are often erased, and in two recent instances (the two NA movies) burnt. I should say how this session was dominated by women: I counted 3 men and 17 women in the audience; the panel was made up of 4 women and the chair was a woman.

I went to two other panels where there the majority of the papers were on women’s writing. I began the conference with a panel held on Thursday, 8 am, entitled “Women Writing Peace and War.” Cathy Rex told how, after having suffered much from war (death) and miscarriage, Ann Eliza Bleecker wrote a fictionalized memoir, The History of Maria Kittle, which was based on a real woman of that name who was taken into captivity. The real woman had thought she had negotiated with one male or a group of Indians to leave her and her family in peace, only to see these same Indians return to her house, murder many members of her family, including all her children, and enslave her as a concubine. Rex seemed to feel that Kittle’s story as told by Bleecker revealed that Kittle’s husband’s unstable, contradictory, & impulsive behavior led to this massacre, after which he deserted her. She thought Maria Kittle a story which exposes a flawed white male patriarchy and shows a woman rightly trying to take the lead. I must say I thought her unrealistically hard on the husbands involved in these incidents. I saw no reason to imagine scenarios which made the Indians’ behavior more justifiable than the white male’s.

Shelley King, the editor of Amelia Opie’s Adeline Mowray, suggested Opie’s poetry fell into 4 phases: the 1790s radical on war and treason trials; from 1802 a muted radicalism, from 1808 yet more indirect, and after 1812, personal. King analyzed two of Opie’s poems from the first and second phases of Opie’s life. She was a long-lived woman and through her father and background remained involved with Quakers. Of the four poems Shelley discussed I thought “Lines written at Norwich on the First News of Peace” (from Opie’s “second phase”) showed best Shelley’s idea that the later Opie had not given up her progressive views, but changed their expression:

What means that wild and joyful cry?

Why do yon crowds in mean attire

Throw thus their ragged arms on high?

In want what can such joy inspire?

And why on every face I meet

Now beams a smile, now drops a tear?

Like longloved friends, lo! strangers greet,....

Each to his fellow man seems dear.

In one warm glow of christian love

Forgot all proud distinctions seem;

The rich, the poor, together rove;

Their eyes with answering kindness beam….

Blest sound! blest sight!....But pray ye pause

And bid my eager wonder cease;....

Of joy like this, say what’s the cause?....

A thousand voices answer…’ Peace! ’

O sound most welcome to my heart!

Tidings for which I’ve sighed for years!

But ill would words my joy impart;

Let me my rapture speak in tears.

Ye patient poor, from wonder free

Your signs of joy I now survey,

And hope your sallow cheeks to see

Once more the bloom of health display.

Of those poor babes that on your knees

Imploring food have vainly hung,

You’ll soon each craving want appease,....

For Plenty comes with Peace along.

And you, fond parents, faithful wives,

Who’ve long for sons and husbands feared,

Peace now shall save their precious lives;

They come by danger more endeared.

But why, to all these transports dead,

Steals yon shrunk form from forth the throng?

Has she not heard the tidings spread?

Tell her these shouts to Peace belong….

‘Talk not of Peace,....the sound I hate,’

The mourner with a sigh replied;

‘Alas! Peace comes for me too late,....

For my brave boy in Egypt died!’

Poor mourner! at thy tale of grief

The crowd was mute and sad awhile;

But e’en compassion’s tears are brief

When general transport claims a smile.

Full soon they checked the tender sigh

Their glowing hearts to pity gave;

But, while the mourner yet was nigh,

They warmly blessed the slaughtered brave:....

And from all hearts, as sad she passed,

This virtuous prayer her sorrow draws:....

‘Grant, Heaven, those tears may be the last

That war, detested war, shall cause!’....

Oh! if with pure ambition fraught

All nations join this virtuous prayer,

If they, by late experience taught,

No longer wish to slay, but spare,....

Then hostile bands on War’s red plain

For conquest have not vainly burned,

Nor then through long long years in vain

Have thousands died and millions mourned.

It strikes me this is also a poem written from a point of view not typical of a male.

Amelia Opie’s grave in Norwich

Anna Lott discussed two radical plays by Elizabeth Inchbald, The Massacre which was totally suppressed, and A Case of Conscience, a play with similarities to Shakespeare’s Othello. The plays show Inchbald’s fear of despotism, male parental tyranny; Inchbald turns to the individual family unit as a place where reform must begin. It has an incident which anticipates the imprisonment of the heroine in Inchbald’s Simple Story.

Ann Bleecker and Amelia Opie were writing in the same period to the same effect as Charlotte Smith about whose Old Manor House and novel, The Minstrel (recently identified as by a woman author) I heard a paper by George Drake in the next session on “Gothic Romanticism and Politics.” Set during the 15th to 16th century wars of the “roses” in England, The Minstrel is an anti-gothic which de-mystifies the genre; Smith shows that laws, customs, a set of values that elevates gain and aggression before all this are responsible for the real oppression and losses her characters experience. The hero, Orlando, confirms patriarchal structures, is passive over getting a job. The past does gain ascendancy over him. The Minstrel juxaposes gothic and history; Old Manor House intertwines the two. Drake felt that in general in conservative texts of the era, gothic (& evil) are localized in a particular phase of history; in more radical texts the gothic is ironized and oppression pervasive in history.

Pamela Plimpton gave the second paper on a woman writer in this Gothic Romantic session. Plimpton argued that Barbauld used the gothic as a visionary realm where she could meditate reformist and radical themes. Barbauld’s unitarianism connected her strongly to reformist and elite (high culture) dissenting religious communities; for her a spiritual experience emerges from the sublime and terror narratives.

During the discussion period I suggested that Plimpton’s description of the mood, themes, and techniques of Barbauld seemed to be also an accurate description of Elizabeth Gaskell’s gothic tales: Gaskell was also an idealistic unitarian, well-educated, connected to dissenting communities and a writer of radical and reformist texts. Ms Plimpton said she had thought about the Gaskell parallel and had she world enough and time to become a Victorianist would follow up on it :) The respected Romantic scholar, Stephen Behrendt was in the audience and he suggested that gothic uses hiding places presenting secrets as something aberrant. There was much talk about the chest in Godwin’s Caleb Williams.

Anna Laetitia Barbauld

As to the two individual papers: on Saturday morning in a session on “National Embodiment in the Long Eighteenth Century,” Jack Shear gave a paper on Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple. This is a story of the displacement of Charlotte Temple, an innocent young English woman who becomes the mistress of roving British soldier, Montreville, who moves to America and takes her with him. Mr Shear suggested that Montreville belongs to the “war machine” of the state, and read the novel as about the cost to women of nation building. Charlotte ends up anguished, isolated, despised, and finally dead. We see what happens to women in war.

The last paper on a woman writer I heard was by Antoinette Sol: it seems that although Elisabeth de Faverolles Guenard, baronne de Mere may have written upwards of 200 books and was “a best-selling author of elevated tracts, novels, gothics, non-fictional historal novels, compilations, continuations, travel, plays, translations yet she remained as obscure as her literary fecundity was appalling.” It is hard to find out much about her life for sure, and you have to travel around the world to libraries to read a few of her novels. Faverolles-Guenard was one of those put into prison during the Terror, she got out in 1794; in 1799 she was writing “naughty novels” (they are not porn, but risque); in 1825 she writes her last novel. She knew the Princess de Lamballe; and she dedicates a memoir to Madame de Genlis.

Ms Sol argued that Faverolles-Guenard’s novels are not just negligible; some have real feeling and thought. She has a lot of nuns in her books, and abbots too. Themes include heroines united with a child, greed and cruelty, a desire for retirement. We see in one novel women build a convent in a forest; in others the exploitation of women by drink. Though she writes light bawdy and funny novels, there are tragic undercurrents; she is religious and has a need to write about realities of her life and the lives around her. And of course is writing for money, to put bread on the table. Interestingly her husband wrote under a female name.

Well that’s it, my dear, for papers on women and what I heard on landscapes. I will have one more report on a miscellany of different topics and the half-joking performance of Charlotte Charke’s afterpiece, The Art of Management that I saw acted. And then I hope to write about Portland, the Arlington Club and our time at the Portland Museum.

A later 19th century created Garden, Dessau, Wortliz

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I should mention I picked up very inexpensive (for free) The Letters and Plays of Luise Gottsched, an important 18th century German woman writer. Like an 18th century Italian woman, Elisabetta Caminer Turra, Gottsched owed her access to the press to her husband.

Though a century old, out of print & probably censored, the two-thick-volume edition of Montagu's letters by her great-great niece, Emily J. Climenson, gives the reader a real sense of the woman's life and genius: see Elizabeth Montagu, The Queen of the Blue-Stockings, her Correspondence from 1720 to 1761, ed. Emily J. Climenson, with illustrations. NY: Dutton, 1906.

And I heartily recommend as excellent (informative & genuinely perceptive) Francoise Kermina's Madame Roland, ou, La Passion Revolutionnaire. Paris: Librairie Academique Perrin, 1957.

E.M.

— Elinor Apr 4, 11:20pm # - From Diana:

"Just wanted to say how rich was your blog on the conference! I just read it and was dazzled by it.

Where can I read something about wedding nights in 18th century fiction – is there an academic article on that? And on the change in views on orgasm from Renaissance to 18th century, how fascinating! Is there an article about that?

Will Margaret Ann Doody’s talk be published anywhere?

What an amazing time you had. I loved reading about it, thanks for sharing.

Diana B.”

— Elinor Apr 6, 8:21am # - Dear Diana,

Often there is no academic article on what one hears. The person speaking is trying out an idea, and to get the idea in print would take huge more amounts of work; plus they’d have to get an editorial team to want their work in their particular journal. So the conference functions as a place to present work you can’t present elsewhere without great difficulty & hard work (and often connections too). It can also be a work in progress, part of a larger project.

But someone like Margaret Doody would be published easily. I suspect her paper will appear in the Burney Journal.

Thank you for the praise. It helps: though I know people are reading, I like a reponse, especially about the content. I'm willing to extend the sessions' discussions here.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 6, 8:23am # - Sounds fascinating. I wish I could have attended.

On the topic of wedding nights, Madame Roland is indeed one of the few women to have mentioned hers, and its “surprises” in her Memoirs.

Men were usually less reserved on the topic. See for instance the Memoirs of the Marquis de la Maisonfort.

As for fiction, one needs look no further than Sade, not the great novels, but certainly the short stories. The Marquise de Merteuil, in Laclos’s “Dangerous Liaisons,” also describes her wedding night. Sade may have been a bit underground at the time, but “Liaisons” was a best-seller.

The topic does not strike me as particularly off limits in the 18th century.

— Catherine Delors Apr 8, 5:58am # - I suddenly remembered Anne Sexton’s poem:

“The Wedding Night:”

There was this time in Boston

before spring was ready – a short celebration

and then it was over.

I walked down Marlborough Street the day you left me

under branches as tedious as leather,

under branches as stiff as drivers’ gloves.

I said, (but only because you were gone)

“Magnolia blossoms have rather a southern sound,

so unlike Boston anyhow,”

and whatever it was that happened, all that pink,

and for so short a time,

was unbelievable, was pinned on.

The magnolias had sat once, each in a pink dress,

looking, of course, at the ceiling.

For weeks the buds had been as sure-bodied

as the twelve-year-old flower girl I was

at Aunt Edna’s wedding.

Will they bend, I had asked,

as I walked under them toward you,

bend two to a branch,

cheek, forehead, shoulder to the floor?

I could see that none were clumsy.

I could see that each was tight and firm.

Not one of them had trickled blood

waiting as polished as gull beaks,

as closed as all that.

I stood under them for nights, hesitating,

and then drove away in my car.

Yet one night in the April night

someone (someone!) kicked each bud open

to disprove, to mock, to puncture!

The next day they were all hot-colored,

moist, not flawed in fact.

Then they no longer huddled.

They forgot how to hide.

Tense as they had been,

they were flags, gaudy, chafing in the wind.

There was such abandonment in all thatl

Such entertainment

in their flaring up.

After that, well

like faces in a parade,

I could not tell the difference between losing you

and losing them.

They dropped separately after the celebration,

handpicked,

one after the other like artichoke leaves.

After that I walked to my car awkwardly

over the painful bare remains on the brick sidewalk,

knowing that someone had, in one night,

passed roughly through,

and before it was time.

*********

The poetic rhythms are not direct, and the imagery complicated, nuanced, and perfect for what is being said.

I thought back to that session at a woman’s caucus in a conference I once went to where people were to discuss this topic. The theses were timid, and how (since this was scholarly) hard it was to find any evidence in books about what happens on a wedding night: in Caroline de Lichtfield, an 18th French century novel by Isabelle de Montolieu, I’ve put on line precisely because this is the center of the story, the forced bride refuses to go to bed with her husband; over the course of the novel she discovers he is an ideal person and he grows prettier; in Sand’s Valentine, the forced bride refuses to go to bed in a powerful scene, but then in both we don’t hear about what it felt like in a night when you do go, nor the problems for girls brought up to fear sex and know nothing of it. A man gave a paper about Pamela’s ecstasies over her wedding night and the two men in the audience were embarrassed to present the topic in any other light it seemed. There were but 3 men in the room; all others women.

A good friend (close) once told me her wedding night was one of the worst nights of her life, and the honeymoon just awful; she had not had sex with her husband before marriage; the marriage did last.

I also thought about novels I’ve read about where a marriage is not consummated. Remember Ellen Ashe in Possession. It is the “great secret” at the heart of the novel. The woman is presented as frightened; I’ve come across this in real life (really been told) and the attitude of the male is scorn for the male who doesn’t force and sullen indignation at the woman who is afraid and won’t yield.

“The Wedding Night” brings out the nature of the experience from within when it’s less traumatic supposely; you are merely pushed into violating a physical part of yourself and not sure and then there’s no retrieval. I like the use of flower imagery especially.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 8, 9:40am # - From Nicolle Jordan:

“Hi Ellen,

I write to thank you for your very accurate and flattering description of my paper on the Women and Nature panel. The woman who questioned my use of poetic terms to assess letters was not as skeptical, I don’t think, as I may have thought she was when I responded to her question. She did say she thought I was effective in what I did, but that she was curious as to what I thought about the cross-generic application of terms. Also, just to clarify, my book’s working title (for now) is “Prolific Ground: Women and the Politics of Estate Management in 18th Century British Literature.” I have chapters on Finch, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Sarah Scott, Elizabeth Montagu, and a final chapter on agricultural pamphlets. It still has a long way to go, but that’s how it looks at the moment.

Thank you again for the information about Veronica Gambara. It sounds quite intriguing and as soon as I have a moment to spare, I will explore further.

I look forward to continuing to share thoughts on literature and women, and to your always insightful posts to C-18L.

Best wishes,

Nicolle”

— Elinor Apr 9, 2:32pm #

commenting closed for this article