Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

A few more books & movies to be getting on with: mostly _Clarissa_; _The Children's Hour_ & _The Women_; & _Revolutionary Road_ · 28 January 09

Dear Friends,

It’s been a while since I’ve written a blog listing the books I’ve read through & movies watched & enjoyed enormously. The last time was when I listed the books I read for the course I’ve now embarked upon, “Gothics, Realism, and Other Worlds,” and described & recommended Wright’s Atonement and Rivette’s La Religieuse. As I did then, I’ll list and comment individually on a bunch of books & movies, and then turn to concentrate on just two, this time a novel, Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, and Sam Mendes’ movie with the same name.

Novels: I finished the whole of Richardson’s Clarissa for a 6th time, & found once I got into it, while I wasn’t as intensely involved by a recognition of parts of me in the heroine as once I was, I was gripped enough to keep reading steadily in a highly alert way. As with Trollope’s The Prime Minister (which I’m still listening to & reading, and not yet done with), I felt charged with living emotions and thoughts rising from the text as I went through. For the first time I really had a sense of the work’s shape too, due probably to the concise way the Folio Society set the text up in two large volumes and used illustrations at key hinge-points as a way of demarking crucial scenes & turning points & giving powerful visual resonance to central themes in the novel’s stories.

My strong investment in Clarissa remains: again it drew on my own memories of aggressive sexual maneuvres by boys & jeering from teenage girls when I was young. The blind egoisms of Clary’s family members and friends, the conflicts among the desperate women, all seem as true and accurate as when I first read it more than 40 years ago. I also love the heroine for her inflinching intelligent integrity and am moved by how she ends her life.

I shall not attempt to say more about what I thought of it in the tiny space of even a long blog. That must wait until I write my 20 minute paper on it and Bierman, Nokes & Barron’s film adaptation.

I started, got into, but did not finish Meredith’s Beauchamp’s Career: too tired at night, the text too elaborate and sometimes indecipherable, it is nonetheless a brilliant political novel like Trollope’s, with the difference that Meredith uses real people as prototypes and analyzes specific political agendas. And tonight I began the German mid-20th century poet’s novel, Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina (translated into English by Philip Boeum), a cross between a variant on Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, Max Frisch’s I’m Not Stiller, Graham Greene’s peculiar disquieted sordidness.

Criticism: I’ve read much criticism of Richardson’s novel and more books on film. The ones I’d like to recommend are: Mark Kinkead-Weekes’s SR: Dramatic Novelist: filled with subtle evolving insights into the characters as he moves through the ficition with them; he also outlines a consistent vision of ideals vis-a-vis human reality he thinks consonant with Richardson’s own. I’m not sure Richardson was so humane or socializing, but do feel Kinkead-Weekes’s book remains the best one on Richardson’s fiction in print. Janet Todd’s Womens’ Friendship in Literature how the women in the book are twisted results of the male hegemonic system is superb; her book captures a central reality of women’s book: the community of women, how they are faring. Pam Cook’s Gainsborough Pictures, where essayists really go well beyond the literal or suggestive content of the films to discuss how they were produced, by whom specifically, how the particular group of individuals pulled the feat off, and how the product has been reviewed. Robert Giddings’s The classic Serial on Televison and Radio is all that I would want such a book to be, from outlining the concrete workings and politics of the eras, to listing the many costumes dramas, and analyzing key ones in terms of issues raised. Apparently Clarissa was a landmark in the new flowering of the costume dramas of the 1990s. His Screening the Novel is a genuine attempt to show the difficulties of translating the myriad complexities and sources of a book from a previous era into a movie form intended to please audiences today, itself a product of commercial as well as aesthetic & thematic aims.

Made into sisters: Clarissa, fake Lady Betty, Mrs Sinclair (Saskia Wickham, Diana Quick, Cathryn Harrison, 1991 Clarissa)

*************

Plays: we are reading women’s plays, stage- and film, on WWTTA for the next six months at least. So I’ve read Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour and Clare Booth Luce’s The Women; I then watched William Wyler’s 1961 The Children’s Hour, George Cukor’s 1939 The Women and have made it my business to resee Diana English’s 2008 The Women. What to say of these?

On Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour. Throughout much of the play & film, women loving women is treated as a terrifying deviant horror. In the last half hour when it emerges that our heroine, Martha (played by Shirley Maclaine in the movies) loves Karen (Audrey Hepburn), and has suffered badly all her life from prejudice and self-hatred, particularly when she cries and admits her feelings, after Karen’s fiancee, Joe has left Karen (and seen her as a sick pariah who needs pity and treatment), we sympathize. When the hateful girl child (a hideous lying bully) is made to own up her lie, and her grandmother comes to apologize, Karen makes her famous speech about not accepting this apology because her and her friend’s lives have been ruined, I was deeply moved. Mostly, it was Martha’s suicide, the ending of the film, for once a piece of utter integrity that did it. Wyler (the same man who made The Ox-Bow Incident) makes no concessions.

Karen (Shirley MacLaine) looking at herself in the mirror (1960 Children’s Hour)

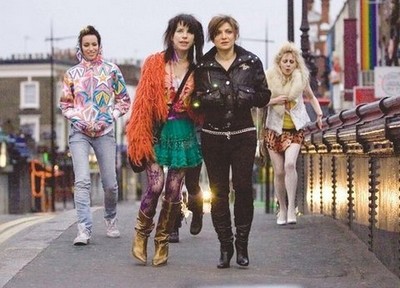

The problem is we’ve come a long way beyond this. A few weeks before Yvette & I had gone to see Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky where, if still socially-marginalized or ignored, disbelieved, and occasionally scorned condition, women’s love for one another was treated as a joyous state, in the move, much freer, relaxed, and burden-free than heterosexuality. And Happy-Go-Lucky is more accurate about what can make life wearisome too:

Coming home from abrasive clubbing, Poppy (Sally Hawkins) & Zoe (Alexis Zegerman) & friends (Happy-Go-Lucky)

Clare Booth Luce’s The Women: the original play and Cukor’s 1939 movie are women’s nightmares of one another. They are first of all, bad for women, the way reading Huckleberry Finn is demoralizing and distressing for many American blacks. bad for women. What do I mean by that? This past week I was trying to put in a new bookcase in my house and moving stuff about and I just felt I was so inadequate at what I was trying to do. I remembered watching this movie which has presented all women as hopeless and incapable and realized the movie had depressed me in the sense of making me feel incompetent. Satire can have this cruel effect.

I’m breaking my own custom and writing of what is awful. My excuse is it’s importantly awful because it’s still done. The play may be read as revealing the hardships of women’s lives: like pregnancies, lack of money, dependence on men. But this is outweighed wholly by the depiction of women as often or mostly mean, stupid, spiteful, ruthless rivals; even friends (Sylvia) betray their friends (Mary) and how? by telling her of her husband’s affair with a hairdresser (among other things the play is classist) so that Mary will leave him. One of the play’s morals is you (women) must learn to overlook your husband’s affairs for it will end up worse for you if you leave him. In the recent mini-series, Lost in Austen, the heroine’s mother again tells her that she should not be so fussy in choosing a man for life. Better any man than none are the words given the actress to say.

Here is a line which captures Luce Booth’s play’s outlook: “As if any woman needed to go to a psychoanalyst to find out she can’t trust women.” The level of conversation among them reminds me of when I was 12 to 13 in a group of girls. Yes they were often hectoring to one another. But I left such groups and while some may remain with snarky minds, much of the viciousness was immaturity, ganging up as a kind of mob, to protect themselves. Booth Luce presents women of 40 and more as having the minds and hearts of such 13 year olds.

The 1939 film erases what is at least somewhat sympathetic to women in the original. These women are not dependent and in need; they want meal tickets and an easy life and are sentimental fools or nasty tricksters or hardened coarse ruthless and amoral. The dislike of women and caricature of them is thorough and relentless. Especially Joan Crawford as Cystal Allens is a total hypocrite, ugly mind, nasty, and a man-trapper. Norma Shearer as Mary Haines is a sobbing fool who learns her lesson that she must fight for and protect her man against the preponderance of nasty women around. Joan Fontaine is a dumb blonde ecstatic at pregnancy. The final scene of gush where Mary runs off into the arms of her now penitent Stephen (well for the moment) was appalling. Russell as a character Sylvia is not spiteful, just stupid. The classism is strong and aimed at the women. They are damned both ways. There are black women, all servants (including the actress Butterfly McQueen). I may the fashion show is also a satire on women, but it went on so long, lovingly, and in color, I felt I was supposed vicariously to revel in a style of glamorI’ve never liked as over-the-top false.

Was there nothing intelligent in the movie ? Well, Mary Boland. She plays the Countess, a role thoroughly rewritten in 2008 for Bette Midler I now realize. In the 1939 movies, the language turns her into a recreation of the Wife of the Bath. She has had 4 husbands and is working on her 5th; the same really subversive humor is used, and Boland is funny. She was indeed Mrs Bennet in the 1940 P&P and thrown away there I now think. As the mistress of one of the other heroine’s husbands, Paul Goddard is quietly pretty, and her cynicism comes across not as mean-minded, but a survival technique.

More good-natured than most of the comedy: Rosalind Russell (comedienne here), tearing the hair out of her rival, Paulette Goddard’s head, while the good Norma Shearer, dopey Joan Fontaine, and amused Mary Boland look on (1939 The Women)

The one consolation in watching it is the thought it could not be made today, and that the 2008 film by Diane English softens all the portraits, turns the women into a partially supportive community (much like the women in Friends with Money, and closer yet, Sex and the City). I found the stills in the 2008 film (starring Meg Ryan, Candace Bergman, Annette Benning, India Ennenga, Jada Pinkett Smith) made the women appealing and vulnerable, forced into roles they don’t want. Some show them companionable (a sequence at a woman’s camp), many simply enjoying aspects of life having nothing to do with men:

The contemporary 3 generations, mother, daughter, & granddaughter, India, basking in the sun (Candace Bergen, Meg Ryan, and India Ennenga, 2009 The Women)

While away I once again saw the whole of Harriet O’Carroll’s Aristocrats once again, and got a sense of the work’s deep melancholy as seen in the lives of the four sisters. On the whole one characteristic which unites all the women’s plays and films we’ve read, watched or discussed on WWTTA thus far, and this includes the remarkable Paradise Road (starring Glenn Close, Frances McDormand, Pauline Collins, Jennifer Ehle, Clare Blanchett et al, based on the true story of women and children thrown into a Japanese prison camp and whose experience of shared adversity brought them closer together and helped overcome petty rivalries and class distinctions), based partly on a memoir by a nurse, Betty Jeffery’s White Coolies)—one characteristic is the centrality of women being together in groups, whether as girls in schools, teachers, or later friends and sisters, and the importance of this relationship to them all.

A very ill aging Caroline Lennox (Serena Gordon) remembering the painful past as her 3 younger sisters listen (1999 Aristocrats)

*************

I came to read Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road through a thread started on either Trollope-l or WWTTA due to my good friend, Catherine C. She called my attention to a skewed account of Phyllis McGinley in the >New York Times Book Review: a wry implicit proto-feminist and light satirist of the 1950s was turned into a complacent housewife-poet, someone who wrote in sheer reaction against Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique. She then got to talking (as well as writing emails we got onto the phone) of Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, a novel about the same 1950s, about the Connecticut suburbs, a raw angry version of John Cheever’s outlook apparently. The first film adaptation starring Kate Winslett as April and Leonardo DiCaprio as Frank Wheeler had just been made and released to theatres, and already garnered some Oscar & Golden Globe nominations.

Catherine was kind enough to send me a second copy of the book she had in her house, and I devoured it at night over 3 sittings, and went to see the movie by myself (in a crowded assembly) this weekend.

The book powerfully combines the genre of novel of manners with a surreal atmosphere, charged bitter satire, and compassion for the chief suffering characters. A quick way to understand its meaning is focus on the play within the novel: April Wheeler (played in the movie by Kate Winslett) and other local citizens have mounted a performance of Robin Sherwood’s Petrified Forest (also made into a movie, starring Leslie Howard and Humphry Bogart); the play’s themes and characters provide explicit parallels to the books. The novel shows the exhaustion of the American dream & exposes the realities of frustration, loneliness, meaningless, underneath a norm celebrated of individualism and monetary & social success.

Life in the 1950s in the US in the suburbs is a kind of lightning rod for many dissatisfactions about life in general; it captures middle class angst, despair, disillusion. I watched Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm shortly before Xmas (a brilliantly written, directed, filmed and actred movie & screenplay I never got a chance to write about) and found it covered this territory too. Such story and character matter seems to provide a shortcut to a genuine deep pessimism about all sorts of American goals and professed beliefs about family and success. The remake film, Todd Hayne’s Far from Heaven (which Yvette & I saw a couple of years ago now) is another variant and was made twice.

Kathy Curtin wrote on the book in her insightful Book Journal:

“The protagonists, a couple named Frank and April Wheeler, never intended to live average lives. They enjoyed their slight rebelliousness in Greenwich Village until April became pregnant, the contingency on which their lives hinge. Frank talks her out of an abortion (which was a perilous and horrifying prospect, since she intended to perform it on herself with a syringe), but the pregnancy in fact ruins both their lives. April has no life outside the suburb; Frank, who prides himself on doing nothing at his job and not even knowing what it is, rebels at work, hilariously shuffling files from his in-box to his desk drawers to the secretary’s files and back to his own in-box, writing brochures and letters as seldom as possible. April, however, stuck at home, has lost confidence. She encourages him to quit his job and move to France, where she can support the family.

It is a, ironically, a madman who understands their philosophy. John, a schizophrenic mathematic, articulates their loathing of suburbia …”

I understand why the book is not appreciated by academic critics and many people: they don’t like this nihilism and despair and feel that people can make a meaning for themselves outside of the daily round or through it. Perhaps had Yates connected the sense of meaningless to some larger critique of the capitalist system (instead of simply mocking it as asinine selling techniques) or given some of the characters some connection to something better or more meaningful than selling houses.

It really did remind me of Henry James by the end. The book ends on a fatuous real estate lady, Mrs Helen Givings (played by Kathy Bates) making sneering comments about how the Wheelers didn’t keep their house up—this left dirty and poor Frank who was making a path (the way some of my neighbors position their grass) ruining the house as this kind of thing is just not done or not fashionable. She was the mother of the man put in an insane aslyum for throwing a chair at her. At one point Frank Wheeler (Leonardo DiCaprio) throws a chair at April. Her husband gets through life by turning off his hearing aid. The Golden Bowl ends on Fanny Assingham. An ass, with Fanny referring both to the behind and vagina. But there lacked this true streak of the sinister and ferocious at the heart of things, searing, rather it was angry, depressed.

For me the book is a kind of a comfort book because it’s comforting to me to see others suffer in the same way I and others I’ve known have, to see hard truths about suburban and contemporary life. Again I find Yates compassionate. As Kathy says, we sympathize with Frank’s desire to stay in his job once he is offered a promotion. The money could then possibly help them eventually to see more of the world and enjoy it. The description of the actual family backgrounds of April (deserted by mother and father) and Frank (nagged by a mother who never got close to fulfilling herself, pressured by an unsuccessful dim father) and are true to life.

The family album picture (as Wheeler family, Leonardo Caprio, Kate Winslett & 2 children)

The movie (directed by Sam Mendes and he’s one of the producers, screenplay John Haythe) is a remarkably faithful adaptation, but then the book (to some extent reminding me of Graham Greene’s work in this) is very movie-like: the scenes are easy to turn into dramatic dialogues; while there is much inward soliloquy or free indirect speech, just about all the explicit ideas of the book may be turned into drama. Not the implicit ones: an important sense in one of the male characters, Shep Campbell (David Harbour), that he and April Wheeler might have made it together because both are intelligent. They have sex once in the back seat of Campbell’s car, and like Frank with his secretary, April does not want to do it again. She acted out of a need to just do something passionate.

The parallel between The Petrified Forest and the story and characters in this book is never drawn. All we have is John Givings (Michael Shannon), the man in the insane asylum as the symbol of what social life as presently carried on or arranged can do to the sensitive or someone who wants to do something genuinely meaningful or with integrity; John Givings had no particular talent or means or connections to reach a place where he could act out any of his gifts and be supported by a salary. All he can have is a mediocre job and house in the suburbs to watch TV in.

What happens at the end is April Wheeler gives herself an abortion to avoid yet another child and dies of it. This looms larger over everything else as it’s so dramatic. It is a form of willed suicide. So we are left with a heroine who died because she was stifled and frustrated with nothing to do worth doing for herself personally. Her husband has a job to go to at least, some respect and autonomy there and we see he entertains himself with affairs. She appears to find no satisfaction in her daily round in the suburb; her children bore her and are gone most of the time to school anyway. So instead of projecting a generalized despair at the limitations of what we are offered in life the movie becomes a parable of a frustrated housewife and philandering husband. It can be seen as having the moral of Friedan’s Feminine Mystique (and thus connect to the social satire of McGinley).

The movie also functions as a kind of warning lesson about what can happen to you if you don’t accept what’s on offer, if you dream absurd dreams. The high point of the Wheelers’ life as we see it is their plan to go live in Paris on her salary; they can’t even collect any money on their house if they sell if as they have paid so little into it. She ends up dead, and he all alone in an apartment near his job in the city, with their two children given away to his brother and his brother’s wife.

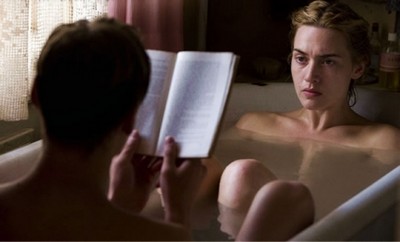

Poor Kate Winslett played the heroine who is both victim and preyer in two movies at the movie house the day I saw RR. For both she rightly has been nominated for Golden Globes and Oscars. In one, Stephen Daldry and James Hare’s The Reader, she is an ex-Nazi concentation camp person who is wrongly made a scapegoat, cannot confess nor tell that she was not singularly guilty, cannot convert easily (the movie exposes the fallacies of stories like The Christmas Carol), not even over a long period of time can she change herself easily, and when, after spending a life-time in prison and about to be released, she does reach out and is rebuffed by the young man she once exploited and now grown old and her only hope for help (Ralph Fiennes), she kills herself.

Michael Berg (Ralph Fiennes when young after sex), reading to the illiterate Hanna Schmitz (Kate Winslett, 2009 The Reader)

The Reader is about profound injustice and how one cannot retrieve great wrongs and right them with a woman the tragic victim/destroyer/colluder. (This one I saw with Yvette after I returned from the UK and was much moved and wrote about it on Inimitable-Boz when we talked of false conversions in novels). I don’t know that there is profound injustice in Revolutionary Road; but here too Kate played a victim/destroyer/colluder.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Kathy:

“I read your blog with interest. I’m sure if I saw The Women again I’d agree with you. I saw it long ago, and if I’m remembering correctly, thought it was humorous. But I barely remember it. As for Rev Road, I still haven’t seen the movie … ”

— Elinor Jan 29, 8:56pm # - From Catherine Crean:

“One thing that comes to mind when I read your posts about Yates is that he was, if I recall correctly, a Flaubert devotee. I think Madame Bovary was one of his favorite books. (He also admired F. Scott Fitzgerald and Keats.

C.”

— Elinor Jan 30, 10:18am # - In response to Catherine,

I wonder what women writers Yates read. The movie is presented as the story of a woman’s frustration as well as a man’s, and (very unusually) April Wheeler is not presented as devouring, cold (she is passionate when happy), nor overly sexy. No male critic (and in the 1950s there were very few females) would report this kind of reading, and Yates would not present himself as a devotee of womens’ books. To say you are a Flaubert devotee or be said to be is prestigious. But the 1950s saw many proto-feminist books and poetry, which is where we began our talk on Revolutionary Road, remember?

This citation of older books shows what is (or was) wrong with English studies. Cultural studies is an attempt to change this but they have to read such idiotic magazines and theoretical works to enable them to attach the idiocy to Yates. Proabably it's closer to the truth than Flaubert whose book is actually misogynistic. Flaubert's Emma asks for her punishment. April doesn't.

I'd lay a big bet it was contemporary books Yates read that influenced him and not Kerouac (endlessly cited). In the article I put on Trollope-l, two other male novelists of manners of the period were cited. But many many women were writing & published, and the preponderance of novel readers were and still are women.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 30, 10:20am # - From Catherine:

“Initially I had trouble with RR because I found April Wheeler a complete cypher. It wasn’t until I read your comments that I started to understand and appreciate her character. Yates had a very troubled life. I think he built a carapace around himself. I think in some cases during interviews he said things he really didn’t mean in order to sound more “literate” or more “macho.” I read the only biography of Yates I could find. (A Tragic Honesty: The Life and Work of Richard Yates by Blake Bailey.) Although it was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, I found it an unsatisfying book. Some critics thought so too. Yates taught for while, and he also wrote speeches for Bobby Kennedy. Yates suffered, and I do mean suffered, from severe alcoholism.

His short stories are interesting – they remind me of Fitzgerald. One of the short stories contains a terrifying scene of homophobia. I get the impression that Yates may have had problems with not seeming manly enough. Yates’ mother was an artist. I don’t know what women writers he may have been interested in, but I get the impression that strong women both scared him and fascinated him.

Kate Winslet really wanted to do RR and begged Leo DiCaprio to be in it. I don’t think this film could have been made without the combination of Mendes, Winslet and DiCaprio. I hope Howard and I get to see the film tonight. Mendes filmed scenes from another film (not yet released) at Howard’s railroad. I think he likes trains!

I wrote something (for myself) about watching Mendes film the Grand Central Terminal scenes in RR. I can send it to you if you like. it was a fascinating experience to watch Mendes work.

Catherine”

— Elinor Jan 31, 7:29am # - Dear Catherine,

There’s an important woman short story writer of the 1950s whose name escapes me. Her stories were published in the New Yorker and she was part of the Elizabeth Hardwick, Lowell-Bishop crowd. Like some of them she became alcoholic. She was for some time put in an aslyum. Natch.

Her stories are in the simple style fostered by Hemingway and Fitzgerald, but the content is diferent and that’s what I’m getting at. Remember Fitzgerald said the rich are different and yearned to be one of them. This is outside Yates’s interest altogether and Fitzgerald wrote 20 years before Yate.

Yates’s fiction has April silent and does not go into her mind so there is this big hole at the center, but the what’s in that hole matters. April had intelligence Frank lacks, that’s why she can’t bear to hear his talk. We’ve mentioned the woman short story writer I’m trying to remember on WWTTA in the past.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 31, 11:45pm # - Having watched the Anita Loos, Jane Murfin, George Cukor 1939 carefully, I rewatched Diane English’s 2008 film and have some scattered thoughts & questions to record.

First question? When is a work a new work? English’s 2008 The Women more or less follows the story line and has a number of the key incidents of both Clare Booth Luce’s play, The Women and (what for shorthand I’ll call) Cukor’s 1939 The Women; but the actual words, and motives of the scenes, nuances of the language, and who is literally responsible for what is changed are sufficiently changed so it may be argued we have new play. In many cases it seemed to me the change was in the direction of greater kindness, a support system, genuine sympathy for women. But not all. On the other hand, much remains the same. The joy of existence is still romance; mothering is still a central function though in both movies only a few women have children. Most appear not to.

So to catalogue some: in Luce’s and the 1939 The Women, Sylvia (Rosalind Rusell) wants to tell Mary (Norma Shearer) about Stephen’s affair and sets her up with the manicurist. In the 2008 Sylvia (Annette Benning) fears Mary (Meg Ryan) may be pregnant, but still does nothing to tell her; it is chance that leads Mary to go to the same manicurist. Sylvia does not decide to tell Mary; rather it is the woman novelist, here not some sexless ugly woman (hiddenly a lesbian perhaps), but the attractive and overtly lesbian Alex Fisher (Jada Pinkett Smith) who prods Sylvia in telling because she genuinely believes Mary ought to know and do something about it. Mary and Sylvia have a loving relationship in 2008 (not in 1939) and when Sylvia gives Mary’s story away to a magazine, she is driven to do it to protect her job. Sylvia is supporting herself in 2008; in 1939 she also “lives off” a husband. Mary feels more betrayed by Sylvia than Stephen and their quarrel and making up is similar to a pair in Sex and the City. It’s part of the climax of the film. But Sylvia is sympathized with or pitied: without a man she is in trouble, for as she ages she is being forced out by new young women.

In 1939 Mary is abject and when at the end she thinks Stephen is coming back, she stands there by the phone all gratitude and submission. In 2008 Mary has become a fashion designer and when Stephen calls, Mary (very like Millicent in Congreve’s Way of the World) is making terms: Stephen will have to accept a wife with interests of her own. 2008 Mary is not simply sweet, and has longed to have a job or success of her own. Nothing like this in 1939. The mother is both movies is the same; the woman must ignore the philandering and accept it. That has not changed an iota. I did like that in the 2008 film Mary’s ability to put on a fashion show is explained: she borrows the money from her mother. So this is not a fairy tale quite. Where money comes from is explained. 2008 Mary’s servants do worry where their salary will come from when Mary throws Stephen out.

The 2008 daughter, Molly (India Ennenga), is presented as thinking she is fat when she is thin. We see her incultured to look sexy and to smoke cigarettes to stop herself from eating. She is not an innocent as 1939 Molly is. A critique of bodily demands on women is offered through the child in 2008. Sylvia befriends her and they have a little talk about sex. Something utterly beyond the 1939 Molly. The new young women rivalling Sylvia at the office for her job are ruthless and present snarky ideas that are anything but humane and feminist as ways of selling the magazine. One says we ought ot have a magazine with the theme of revenge (on other women it’s implied). How to stick it to them. This is what wins out with the manager as the next issue. Sylvia has some real feminist ideas (we are not quite told what they are), but they won’t sell. On the other hand, the 2008 mother (Candice Bergen) has a face lift and the attitude is if this makes her happy, good. This is very like the mother in Lovely and Amazing, a woman’s film.

Alex, the woman novelist is still someone not interested in men. There is still a woman endlessly pregnant: in 2008 it’s Edie Cohe (Debra Messing), but she is not downtrodden or tired or irrated by it as in 1939 but ecstatic. On the other hand, there are jokes about breast pumping. She pumps her milk from her breasts by a lighter in the car. So the wild irrationality pressure has driven women to perform over breast feeding is noticed in this movie (a recent article in the New Yorker by Jill Lepore exposed this aspect of breast-feeding for modern women.) It’s was not make much of; if you blinked, you missed the joke. But it was there.

Actually Bette Midler (a transformed Countess) was less funny than Mary Boland. Boland was genuinely subversive and mocking. Midler gave Mary advice to be selfish. The role was not funny really, rather sincere, earnest and wholesome in its presentation of earthiness (rather than ribald). I found that interesting. There is not equivalent of Paulette Goddard (the second mistress, rival to Sylvia in the 1939 movie) who is out for survival; the simpleton western-type woman is dropped (a caricature not longer working I suppose). I’d say the 2008 movie was not funny, but rather comic in structure. It reminded me of Sex and the City, and Friends with Money for the women were supportive.

Black woman as universal servants were dropped. The only black woman in the film was Alex, so the only black. Servants were white or Spanish looking so the US class system was hinted at (Crystal is Spanish).

A joke in the 2008 movie is Crystal runs off with Alex’s latest partner. She’ll take anything is the joke? But a scene is set in a lesbian bar where everyone seems happy and there is no aggression. Crystal is still a hypocrite and there is a scene in a dressing room which is the same in both, but she is not given anywhere near the nasty lines of the 1939 Crystal (Joan Crawford).

2008 ended with the women helping Edith (Debra) to have yet another baby. A son. So we have a boy and they are ecsatic. That it’s painful and hard work is shown, and yet it’s over quickly and everything goes well like magic. The 1939 movie ended with the planned calculating exposure of the overtly nasty Joan Crawford as Crystal.

So although once in the 2008 film Mary says “women” disgustedly, there is no animus against women in the same way as the 1939 film at all. The 2008 film is not a satire, mean-spirited or mocking or debasing or otherwise, of women, but sympathetic to them although not showing a feminist set of values strongly. They are there, but mildly.

Still the moral was you should hold onto your man and take him back and fight other women for him, and he is in danger of man-trapping other women. He is your meal ticket against aging if you can hold onto him. And what mattered at the end to Mary was not her success at fashion so much as getting back Stephen. She was not sure she would take up a buyer’s offer to spread her wares to Sack’s throughout. She was worried lest she not have enough time for Molly and looking forward to seeing Stephen next Tuesday night. If asked to imagine happiness, it’s romance with a man except for rare birds like Alex.

A complicated film reflecting seriously and comically the realities and perceived pressures but also fantasies of 2008 in modern upper middle class communities, especially those of big cities.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 31, 11:49pm #

commenting closed for this article