Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Poetry & foremother poet postings, pictures & groupsite stills · 10 February 09

From Paradise Road (1997): if you look hard, you may glimpse Glenn Close, Frances McDormand, Jennifer Ehle, Elizabeth Spriggs, Pauline Collins, Cate Blanchett

Dear Friends,

Over the weeks since the Womo poet festival I’ve resumed writing and putting up on Wompo each Friday a foremother poet posting; on Women Writers through the Ages on Yahoo each Tuesday found and shared a poem by a woman with others and some of our members have sent poems in too (I do this for 18th century poems on Eighteenth Century Worlds on Yahoo and for 19th through 21st century poems on Trollope-l on Yahoo), and I keep putting up pictures on the groupsite pages and sometimes changing my pictures on my website.

This morning I thought I’d record the names of women poets, and share one posting about an earlier women poet, a couple of poems and few picturse and one still from a movie worth seeing.

The foremother poets have been

Henrietta St John Knightley, later Lady Luxborough, (1699-1756), Hester Salusbury Lynch Thrale Piozzi (1741-1821),

Constance-Marie de Salm-Dyck (1767-1845),

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley (1797-1851),

Anne Bronte (1820-49),

Rosalia de (or da) Castro (1837-1895),

Voltairine de Cleyre (1866-1912),

Stevie Smith (1902-1971),

Phyllis McGinley (1905-78),

Robin Hyde (1906-39).

Next up (this coming Friday) is Mathilde Blind (nee Cohen) (short essay on her by Angela Thirlwell in Times Literary Supplement, October 2008, pp. 14-15), Victorian poet, highly unconventional woman, lover of Ford Madox Brown, committed feminist and agnostic, painted by Lucy Madox Brown.

My guess is Knightley, Salm-Dyke, Castro, Blind, Cleyre and Hyde are hardly known to any wider public than those interested in poetry, the era they lived in, politics, or nationalism (the subject their various poems may be categorized under), though there is a recent historical novel (Vingt-Quartre Heures d’une femme sensible) based on the radical french saloniere Salm-Dyke’s life, Castro’s Spanish Galician songs have been set to music, and Cleyre (named after Voltaire by her father) makes it into articles about American socialists and radicals at the turn of the 20th century. So I’m torn which one to celebrate individually here. I have written about Knightley here and I’ve not “done” Blind as yet, so that leaves Robin Hyde who I choose mainly because I like this poem by her:

Quietude

Along the crumbling walls grey lichens creep.

Nothing will grow but drowsy poppy seeds

That hold the listless chalices of sleep

In a child’s garden, covered up with weeds.

I will go now and find some ordered place

Of lawns and old-time gardens, where the earth

Has grown with aging like a lovely face

That is not greatly stirred by any mirth.

No passions storm or sadden in her eyes;

No follies jingle bells along her street;

And every grief, grown decorous and wise,

Must go his ways with patient lips and feet.

A little smoke from dead-leaf memories

Shall curl, blue-grey; and I will dwell beside

A wood where blackbirds call, where the old trees

Harbour no dreams save those grown quiet-eyed.

Here, where good rain is given to careful lawns,

Perhaps my peace will slowly come to flower,

And I forget the scent of troubled dawns,

The broken petals of a magic hour.

Robin Hyde

Apt for autumn? The poem seems to echo Yeat’s “Lake Isle of Innisfree.” I will go and arise now … where peace comes passing slow …” The slow elegiac earth- or natural imagery reminds me of the Georgian turned WW1 poets (like Edward Thomas or is it Thomas Edwards?). It’s drenched in natural wetness and feels alive.

Iris Guiver Wilkinson, a New Zealander, journalist, poet, novelist, lived an independent unconventional life, often filled with grief. She ended a suicide.

Here are two sites where you can learn about her life. Her lifestory is certainly sad. I noticed how she fought for the causes of the poor, vulnerable, and powerless and how she herself was never given a space to write for real in as a journalist. The going in and out of asylums, and the relationships with men, the dead baby early on , and keeping on fighting. There is a biography, written first by her friend, Gloria Rawlinson, her biography, A Book of Iris, was finished and published by her son, Derek Challis.

Fleur Adcock (one of my favorite poets) is another New Zealand writer. A couple of years ago now I read Jane Mander’s magnificent first person narrative The Story of a New Zealand River (from which Jane Cameron adapted her film, The Piano, which I read, screened, adn then discussed once with a group of students in an Advanced Comp about the Humanities class);

Ada McGrath (Holly Hunter) seen from the back, playing her piano on the beach, surrounded by all her things

This was while I was working on a project about Trollope’s travel writings (he went to New Zealand and his book on Australia includes a long section on New Zealand)

In a couple of days I’ll celebrate Hester Lynch Piozzi separately; precisely because she’s well-known, discussing the biographies about her will bring up revealing aspects of biography and reviews.

********************

On Women Writers through the Ages we’ve been discussing the poetry and life of Ingemor Bachmann (1926-73), and I began with my friend Fran, to read Bachmann’s autobiographical novel, Malina. Fran put this extraordinary poem on Bachmann death as a result of (incorrectly treated) injuries sustained in an apartment fire presumably caused by an unextinguished cigarette:

Ingeborg Bachmann Dies in Rome

Barbara Köhler(translation by Andrew Shields)

One death comes

before another.

Breath and smoke.

And smoke which puts out breath.

And silence.

But sometimes only a cigarette

helps you keep your grip. And keeps

its promises more quickly, too.

Between yellowed fingers

it burns like love becomes ashes

like betrayal. Breath and smoke.

The three fingers of oath curved

around the cigarette: to

not forswear.

Giordano burns on the Campo de Fiori.

The bells of Santa Maria Maggiore

are still pealing for the auto-da-fé.

Breath and smoke.

And smoke which puts out breath.

And to write with

a burned hand about fire.

And the borders of the German language

are mined with murderous accidents.

One death comes before another.

The translation’s final stanza refers to Wittgenstein’s theories on the limits of language since Bachmann was one to experiment with and push language and more and more interested in Wittgenstein’s theories on the limits of language which may be summed up in the following words:

what can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence. Thus the aim of the book is to draw a limit to thought, or rather—not to thought, but to the expression of thoughts: for in order to be able to draw a limit to thought, we should have to find both sides of the limit thinkable (i.e. we should have to be able to think what cannot be thought). It will therefore only be in language that the limit can be drawn, and what lies on the other side of the limit will simply be nonsense.’

The poems also alludes indirectly to Malina. The words ‘to write with a burned hand about fire’ are a much quoted extract from Malina, where the unnamed female writer-protagonist says with my burning hand I write of the nature of fire (an intertextual reference to Flaubert: ‘avec ma main brûlé, j’écris sur la nature du feu’). The book in English Malina’s reminds me most of is Elizabeth Hardwicke’s wild & truthful meditation, Sleepless Nights. We also discussed some remarkable poems and a translation of another by Paul Celan, one of them on Bachmann (who was his lover).

One line refers to the horrific death of Bruno (whose tongue was burned out of its root before he was burnt to death). He was not a suicide, and the implication may be her society drove Bachmann to her seclusion and then accidental death.

********************

As for pictures, after skim-reading Terry Castle’s book on masquerades—as part of my project of reading towards my paper on the 1991 BBC Clarissa (which I hope to begin today), I put the following presumably accurate drawing of a masquerade sceen in the Haymarket, King’s Street by an Italian illustrator, Grisoni:.

My paper on the 1991 BBC Clarissa is entitled: “How you all must have laughed. Such a witty masquerade.” I love the bitterness of the scene between Clarissa and Lovelace from which it comes. As Frank Scott out of Leonard Cohen says: “From bitter searching of the heart, / Quickened with passion and with pain/We rise to play a greater part.”

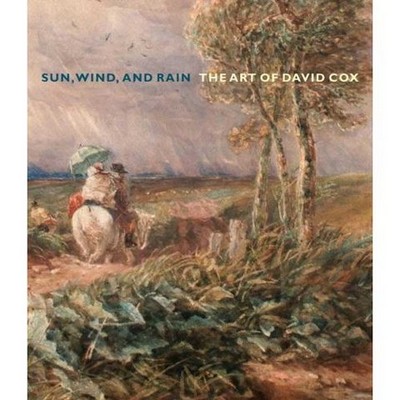

On Trollope-l’s groupsite page, I put two images of pictures by David Cox; first the quietly realistic:

There is a new book: Sun, Wind, and Rain: The Art of David Cox by Scott Wilcox, which accompanies a wonderful new exhibit now at Birmingham Museum. I also put up his celebrated Sun, Wind, and Rain, which I could only find online as the cover for the book:

It is lovely.

After a group of 18th century influences (Canaletto, Girtin) and then early 19th (Turney, Constable), Cox went to Paris where he was influenced by Bonington. He gives the viewer a sense of being there; we see “people huddle before the onslaught of win and wave or go about their daily task in an expanse of sky and light reflected from the sands … you can put your hands on the balustrade of the pier, take a splashy step on the beach …” Cox captures in other paintings “the treacherous Lancaster Sands … the world divides into sky and sand, lashed by rain and menance by clouds.” It’s a form of sublime engaging with the human predicament and natural world” (from the review on the TLS by Patrick McCaughey, January 16, 2008, p. 17).

And I end where I began (see above) a still I put up on WWTTA’s groupsite space after a couple of week’s on and off postings about Bruce Beresford’s Paradise Road (based partly on a memoir by a nurse, Betty Jeffrey’s White Coolies), a film centering on a group of nurses and women passengers treated horrificially by the Japanese during WW2. Here is an essay, which tells the difference between the much softened upbeat presentation—but still truthful enough and effective, moving. The movie starred a bunch of my favorite actresses. Here they are in the fiction: just after having arrived at Sumatra, all eating a tiny mound of rice, before they have been beaten cruelly (only rarely shown in the film), abused sexually (not shown in the film), tortured (a couple of times shown mildly), killed barbarically (once, a woman set on fire):

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Penny on ECW wrote:

“Thanks to members of this list, I have 18th century French art hanging on my walls. And I have more space. So I can then get art from wiki commons. And salivate over the book on my coffee table.

I never realized until I joined this list how much I could enjoy looking at art. I could gaze for hours.

Thank you for showing me artists with a sense of fun as well as great art. I think some of them like Fragonard are more fun than looking at an impressionist.”

To which I replied:

I love art books myself and have two long rows of them in my library. I enjoy putting pictures up on our site. I’m limited here by trying to keep to eighteenth century art and what I have available in my books and can find online. I try to choose tasteful ones too (so that’s another limitation—there is a lot of risque and (to me) gross rococo art I don’t put on our groupsite page).

When I can afford it, and it’s a book filled with reproductions, I buy the book for the exhibits I go to. Sometimes I can find them cheaper later on the Net.

My problem is it’s rare I can sleep more than 4-5 hours in a row, and then if I wake in the night and stay in bed I get dark and unhappy or black thoughts. So I get up and write blogs, read, write letters to friends, tire myself out and return to bed :). It’s not so bad. These last couple of years with studying film adaptations, I also watch these and write about them.

One of my favorite lines from Austen’s books is that by Henry Tilney when he says to Catherine Morland: ‘it is well to have as many holds on happiness as possible’. It’s my screensaver. When the monitor turns to a single color or colors this is the saying that flows around the screen.

E.M

— Elinor Feb 10, 10:58pm # - From Tom:

“Pleased to see Stevie Smith mentioned by you in your latest (have you ever seen the film Stevie, quite good I hear from reliable sources). Have you read any of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s poems? I look forward to your post(s) on Hester T. Piozzi. (An old friend of mine gave me for Xmas one year the 2nd edition of Balderston’s Thraliana in 2 volumes, Clarendon Press, is it 1951? – I enjoy these immensely!).”

— Elinor Feb 11, 12:50pm # - I love that Robin Hyde poem, though I haven’t read much of her work.

I’m also very interested in the picture of the masquerade scene – these seem to crop up quite a bit in novels of the period, and it is good to know how they would have looked.

— Judy Feb 12, 12:57pm #

commenting closed for this article