Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Kate Winslett wins! & more women's plays & films: life such a sad cruel business · 23 February 09

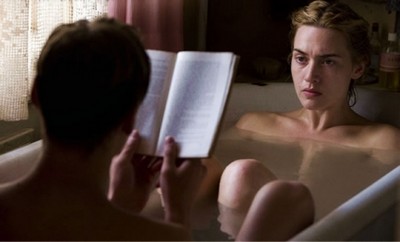

Kate Winslett in The Reader

Dear Friends,

I managed to stay up late last night so was up at a quarter to midnight watching the Oscars awards ceremony with Yvette. We both rejoiced to see Kate Winslett win the Oscar as best actress in The Reader and Sean Penn as best actor in Milk. We had not seen Slumdog Millionaire.

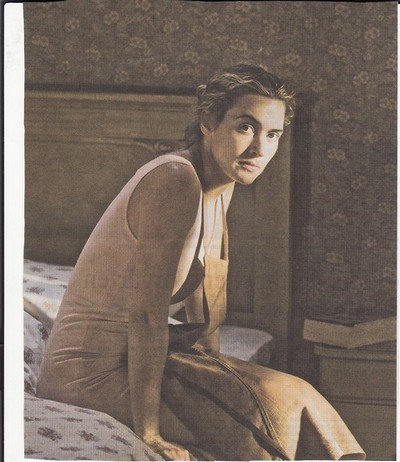

Reuters photo of Winslett outside the auditorium

I feel about Winslett’s win something of the way I did about Helen Mirren’s win a couple of years ago for ostensibly for her acting in The Queen, but actually for her whole long career, so now Kate Winslett wins for having had such a good decade and a half since Sense and Sensibility. She has been nominated for two Golden Globes and one BAFTA. I’ve liked just about all the roles Winslett ever played & the films I’ve see her in: they seem to me serious and engaging with important issues.

I described The Reader briefly in a previous blog on Winslett in Revolutionary Road. Now I’ll say a little more: the film is based on a German book, The Reader by Berhard Schlink, a bestseller in Germany. Winslett plays Hannah, an ex-Nazi officer from a concentration camp who herself murdered many people or cause them to be murdered. The movie shows is she unfairly takes the “rap” (is scapegoated) in place of a whole bunch of such women as she is the only one who will not lie about her feelings or role today. She manifests no remorse or even understanding that she did hideous wrong. Hannah goes to prison for many years and we see how hard it is for anyone to change—especially in the environments she’s put into which are sheer punishment. We see reality is precisely the opposite from what we are given in fairy tales like The Christmas Carol and other swift, complete and forgiving conversion stories.

The story is told from the point of view of a young German man who she picks up and has sex with but also asks to read to her. Hannah is presented as aggressive, fierce, and also abusive of this boy in a way: she is the leader in the sex act, inviting him in, and she orders him about. (There is misogyny here as it’s not likely he would be so docile and she so domineering.

He gradually learns that she doesn’t know how to read is illiterate, and he keeps this information to himself during the trial even though it would have helped her.

Winslett as Hannah working very hard at listening

Ralph Fiennes plays the boy grown into an older disillusioned man, now divorced for whom the experience remained central to his character formation. At the film’s end he is sending Hannah tapes of his voice reading books aloud to her. When it comes time for her to get out, she has no one to help her or turn to. He turns up and it seems he has made an apartment for her. But he does not forgive her, is stern to her and does not show any affection. So Hannah commits suicide.

Nothing is gained, nothing reformed, nothing redeemed. He visits the daughter of someone in a camp who had been there too and this woman just hates Winslett’s character. Only his compassionate eyes (and this is a Fiennes forte) shows us he felt he could have retrieved her and has not.

That Hannah felt deeply is seen only in the suicide. But to take a leaf from Elsa Morante in life and her famous heroine, Irma (I’ve been reading Woman of Rome by Lily Tuck and remember Storia as one of the finest books of the 20th century), Hannah died many years before she committed suicide. She died when she discovered that she was an outsider once the Nazi war was over and illiterate and tried to find some life with this boy. But she had nothing to teach her to reach out. Then she was buried when she was sent to prison. The last scene was just the final interment.

P.S. 3/23/09: A perceptive discussion of The Reader is to be found on a blog called Toyshop (Nick’s blog):

http://movingtoyshop.wordpress.com/2009/03/16/waiting-for-godot/#comments

Nick says, the question of the film is can we sympathize with Winslett’s character. You hit the nail right on its head. I think we are supposed to: why else have her commit suicide? and yet to sympathize with her is to sympathize with someone who shows no understanding of what she did even if she was wrongly singled out and scapegoated because she told the truth and then treated as cruelly as she treated others.

Perhaps that’s it, Nick: we see her treated almost as cruelly (I’ve modified that) as she treats others. The young man grown up cannot stretch out his hand to her and does not bring the evidence to the trial which might have helped her. But he does read to her and get her that apartment. But he makes no overt gesture.

*****************

We have carried on on Women Writers through the Ages reading women’s plays, looking at their films, discussing actresses. Yvette and I did not see Slumdog Millionaire basically because I was so turned off by the trailer and have been busy watching womens’ films,, she watching ice-skating on weekends and I working on my paper on the film adaptation of Richardson’s Clarissa and had watched Paradise Road.

We’ve had some disappointments. Cinemart, our art moviehouse has not changed its movies for weeks. I had meant to see Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy, but put it off for one weekend, and the next week it had vanished. It hardly lasted three days in the local theatres. The story was a true to life one about a young woman in her twenties who can’t get a job and travels with her dog and meets others like herself. Who wants to see that in this jobless world of the US (white collar jobs especially being wiped out)? Apparently the director did lay it on a bit thick as the the girl’s one companion, her beloved dog is at risk of dying and she has no money to pay vets (even more expensive than regular doctors in the US or at least equally). Still I would have loved to have seen this searing indictment of the Bush legacy:

This past three weeks our play was Doris Lessing’s Play with a Tiger. It was a bit of a disappointment: it reads like a dramatization of some the matter of The Golden Notebook. The first part is somewhat realistic and then we have this intense dialogue—in the way the end of Golden Notebook breaks down from stories (and also other parts). Some of the same obsessions: how bad for you are psychiatrists. There is this admiration for the strong man even when corrupt (Dave); Anna Freeman who has a child by a previous husband and also Tom, a British lover (this one betraying himself by going to work as an editor on a woman’s magazine which publishes pernicious pap); Harry, a man who is unfaithful to his long suffering wife who endures this situation because she has nowhere else to turn for money or a lifestyle; her friend, Mary, who has a son and has affairs indiscriminately.

I was puzzled by the tone of a review of the play by Carol Dall’Amico I put on our list. Dall’Amico talks of the matter in this play as if it were some strange anthropologically studied group that exists no longer—implying there are no open marriages and speaking of this with a kind of shudder. It seems to me with the exception of people active in socialism and communism, what is in the play is spot on today only hypocritically hidden. Lessing subdued a central redeeming (!) concept of The Golden Notebook that joy for women is in the love of a strong men to some extent, and concentrated more on Anna and she does critique the joy one is to get from this strong man.

It works like this and Dall’Amico missed it entirely as it seems she can’t see further than her horror of a female heroine who wants to live freely sexually, doesn’t want to be a mother first and foremost, has open relationships. Anna may want to live freely sexually but in each relationship she does want truth and candour and responsibility. She is apparently faithful to the man who is her lover/husband while the relationship is on. In other words, she is not promiscuous nor does she hurt others by abandoning them or lying to them. Well, each of the men in the play is promiscuous. Dave has impregnated a young girl Janet who we are to think did this deliberately (let herself get pregnant) so as to get him to marry her. (This is antifeminism I think; this idea but Anne Oakley says some such idea does fuel women who are against having abortions available; they think without them they can drive men to marry them whose potential child they carry.) He lies about it and is absolutely indifferent to the girl. He’d fuck anything; so too Harry and does; and so would Tom.

This made me remember that the men in Golden Notebook are all unfaithful too – there are many more stories, one is a novel inset where the man (a reflection of Anna’s British lover) is unfaithful to his wife and leads the woman on to think he will leave the wife and marry her. Lessing loathes this in men and can’t understand why they are this way. The tiger is a nightmare male in bed Anna dreams up. Preying on women.

For myself I know among the things women are supposed to accept under the “boys will be boys” rubric is their right to go after all sorts of women sexually. Now in The Women is not the moral Mary is supposed to turn a blind eye to the man’s having an affair elsewhere? And is not this moral alive and well in the 2008 movie? Judy writes of the presentation of male promiscuity here: “In this play, I’m just not sure how Lessing is expecting the audience to react to Dave and his sex life. Anna seems alternately dismayed and charmed, sending him away one minute and telling him “You are my soul” the next.”

In a way I prefer Lessing’s prosaic response to the hysteria (and overreaction) as presented of the woman in Sex and the City, and certainly the exemplary abjection we are to want Mary to exemplify at the end of the 1939 The Women, with Mary of the 2008 not much better (she’s about to give up all she has built as a working life for herself). And Anna herself has had another lover and who knows what she does with all her free time while with Dave. Judy wrote of Lessing’s presentation of male promiscuity: “In this play, I’m just not sure how Lessing is expecting the audience to react to Dave and his sex life. Anna seems alternately dismayed and charmed, sending him away one minute and telling him “You are my soul” the next.”

But that she finds this charming in him too sticks in my throat. Revealingly the same worship of macho males is found in Christina Stead’s presentation of these he-man aggressive types as irresistible to women, and in both of their cases, they call them “real men.” Yuk. And very stupid of them too, especially considering their supposed admiration of socialism and socialist values. Glamor ought to grate but does not. But in fact perhaps what they admire is power; they were high in these political movements, involved with the kind of person who rises high. And these are people seeking power.

Lessing keeps cats, and this is a late novella

I love to make connections across books. I watched Frears’s and Hamptons’ Les Liaisons Dangereuses this week and have been studying Clarissa 1991 (as I’ve come to call the film) within an inch of its life, and after all what is the matter here: promiscuous males. The libertine is not presented as a social problem in this way, but surely we can see it in this light.

In both books and films the male is killed by another at the end. What defines the libertine is promiscuity and he is out to make all women, especially virtuous ones and what a kick to make them promiscuous too.

Sean Bean as a posturing supercilious promiscuous Lovelace dressed to the nines

What makes Madame de Merteuil in Les Liaisons Dangereuses a “man-woman” and such a villain is she is promiscuous in private and gets back at men this way. Lovelace and Valmont are presented as seething tigers in the films.

The older texts do not ask, “What shall we do about this” in this vexed way. And they never suggest a woman should turn a blind eye, or put it this way but after Clarissa is raped and people advise her either to sue or marry him, the latter decision would surely include turning a blind eye. Forgetting. And there are many plays in 18th century English plays where we have reformed rakes. Richardson said he wrote Clarissa to refute the common saying that reformed rakes make the best husbands.

But Lessing seems to think the rake need not reform.

*****************

And now I get to my third theme—I seem often to have three parts to a blog. There really seem to be obsessive motifs we find or repeating ones in plays and films by women (or where women are so central as to exclude men) and are not in this obsessive or dominating way in women’s novels, memoirs, poetry. These are the community of women, lesbianism, and promiscuity of men. Now in girls’ memoirs, the community of women is often shown us, but that is partly the result of showing girls in boarding schools or separated off in groups in school.

From Sex and the City: utterly typical in its use of a community of women as central to women’s lives in women’s films

I ask myself if this comes from the play being a social event, played in front of an audience where all are in a social situation and affected by a sense of what other people think so social values come to the fore and control what is put on stage, especially with anything that is popular or many people go see. Also movies almost necessarily favor social scenes.

Or is it that in real life women are really still thrown together in groups more than I realize? In the pre-modern world they were and excluded from the public world of power and money and property that way, but also kept in their family groups. Now they get together to have book clubs and parties. Mary McCarthy’s The Group comes to mind as a novel that has the focus of these films and plays obsessively, almost.

Well, that has not been my experience in my life span. Not groups of women though I’ve seen it and come near it when I had children to bring up and take places. As to male promiscuity, I really prefer the good male characters like, say, the Austen heroes I like to write about. As a counterpart to Bean, here is a still (not a good one) of my favorite, Liam Nelson’s role in Rob Roy, e.g.,

the nurturing openly vulnerable (when with his woman) man, a type not dwelt upon in these women’s films. Perhaps the obsession with male promiscuity comes from more than hurt and insecurity; perhaps it comes from some vicarious fascination. Lessing (and Christina Stead whose attitudes are like hers) wants herself to be powerful.

Well, not me. I see it. The patterns of quartets of women (& the stupidity of the anodyne wish-fulfillment vampire books) come from the reality that life is such a sad, cruel business and in public we don’t like to admit that. And movies and plays are expensive commodities, need to make money. So we get compensation. See you are not alone. You are in a group.

How often it is that the reality beneath popular pronounced words and presented images is the opposite of what’s presented and the opposite is presented to obscure and compensate for the reality.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article