Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Female Troubadour poetry & Christine de Pizan Imagined · 30 October 05

Dear Miss Vane,

It’s no surprise that the last couple of decades has seen an abundance of films and books in which unqualified admiration is expressed for violent women and of books where the author passionately argues how women enjoy acting out violent, arbitrary capricious & cruel uses of power. Sadeian women, femmes fatales, warrior women (especially when queens) are become exemplary icons.

Let us be strong and clever and above all aggressive, exult in whatever our bodies and minds can and want to do, no matter on behalf of what, no matter who is hurt. Anyone who protests or points out they neglect accountability is into passive aggression or worse a prig. One of the best passages in Angela Carter’s The Sadeian Woman seems not to have been taken to heart. There Carter writes that "one of Sade’s cruellest lessons is that tyranny is implicit in all privilege." A "liberation from the limitations of femininity" may be "gratifying," "may extract vengeance for the humiliations" women have been "forced to endure" as "passive objects," but if it is a "liberation without enlightenment," it "becomes an instrument for the oppression of others" (1979 Penguin, pp. 27, 89)

An excellent anthology of essays I finished reading today, _Gendering the Crusades, edd. Susan B. Edgington and Sarah Lambert, at least at moments provides a rare counterpoint in its sombre and utterly convincing picture of the usual lives of women in a subsidence society whose powerful males live by making war, and whose articulated mores are religious and anti-feminist. Particularly sobering (partly because there is actually some hard evidence here) are the accounts of women taken captive: grim’s the word for the fate of all but a very very few of high rank (who would be held for ransom). In "Captivity and Ransom: The Experience of Women," Yvonne Friedman demonstrates women were routinely, eagerly, sexually abused, often murdered outright if not attractive or exploitable physically in some way. Returning to one’s original home was well nigh impossible unless the woman was prepared to face harsh punishments (for having been raped and abused). The writers are men who attribute motives like sexual desire, laziness, selfishness & inexplicable longings for freedom to women who refuse to comply silently.

Partly to console myself, partly in quest of some glimmer of a better past for women than this I pulled off my shelf a book I had forgotten about, Peter Dronke’s Women Writers of the Middle Ages: A Critical Study of Texts from Perpetua (ca. 203) to Marguerite Porete (ca. 1310) (Cambridge UP, 1984), and began reading the personal poetry of the medieval period attributed to women. I took heart from the following poem attributed to a Countess da Dia (no other name given) from Provence. Not that her life has been any better: her body and spirit have been ruthlessly used instrumentally:

I have to sing of what I would not wish,

so bitter do I feel about him whose love I am,

as I love him more than anything there is;

with him, grace and courtesy are no avail to me,

nor my beauty, merit or understanding,

for I am deceived and am betrayed as much

as I would rightly be had I been unwelcoming.

Friend, comfort me in this—that I never failed you

through any behavior of mine;

rather, I love you more than Sguis loved Valensa,

and it delights me that I vanquish you in loving,

my friend, fro you are the most excellent.

To me you show arrogance in words and presence,

and are well-disposed towards everybody else.

I’m surprized your feeling turns to proudness

with me, friend—and for this I am right to grieve:

it is not fair that another love takes you from me,

however she may address or welcome you;

and remember how it was at the beginning

of our love . . . God forbid

that the separation should be fault of mine.

The great merit that shelters in your person,

and the rich worth you have, disquiet me

since there’s no women, far or near,

who, if she would love, does not submit to you;

yet you, my friend, have enough discernment

to sknow who is the lyoalest.

And remember our understanding.

My worth and my nobility must speak for me,

and my beauty, and still more my loyal heart,

and so I send you, where you are staying,

this song, which shall be my messenger;

and I want to know, my fair gentle friend,

why you are so hard and strange with me

I don’t know if it is pride or evil spite.

But I also want you to tell him, messenger,

that many suffer great loss through too great pride1.

The Countess has held firm to her ethical character and clear seeing. The verses are instinct with dignity, grace, self-esteem and a valuing of peace and kindness.

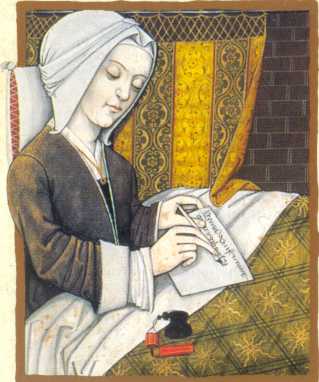

The last 2 times I got to teach English 203 (the first half of all literature, a sophomore level general education course), I read with my students the autobiographical writings and poetry of Christine de Pizan (ca. 1364 – ca. 1431) from the Norton The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan, edd. Renate Blumefeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Pizan’s poetry is filled with a spirit similar to that of the above Countess. On my website I have an imagined image of Pizan I found on the Net, which has become one of my favorites of a woman writing:

I love the colors and serenity2.

Miss Sylvia Drake

1 Dronke, p. 103. I cannot assume the translator is Peter Dronke as Dronke does not say who translated the texts he provides. Instead he will refer the reader to books which contain the original or source texts. In the case of the poem by the Countess of Dia, he doesn’t provide the original Provencal French, but only annotates the translated English text by the following note at the back of the book: ‘A chantar m’er de so q’ieu no volria,’ ed. M. de Riquer, Las trovadores III, 800-2. I have improved the translation in a couple of places; that is, altered the words so as to eliminate clichéd English, made the syntax more forceful, and try for a little more subtle nuance (e.g., where it says "I’m surprized" the other translator had "It amazes me that …"

2 I do not know who made the picture.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Hi, to let you know that you are included in the second Feminist Carnival of Blogs.

— suzoz Nov 2, 7:38pm # - Thank you.

Chava

— Chava Nov 3, 7:19pm #

commenting closed for this article