Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Syriana: Jacobean tragedy brought back · 27 December 05

My dear Anne,

We got through Christmas not only without a hitch but happily, bumpily and noisily. Rob and Caroline came over around 12, and we had cheese and crackers and wine while we exchanged gifts. We were off to a local movie-house to see Syriana by 1:30 and after the movie went to a near-by Chinese restaurant to have a gargantuan spread of dishes (which included Peking duck). Much good talk, lots of wine, and a brief stroll out in the warm rainy evening together ended the precious moments.

This blog is not about that though: it’s about Syriana (directed by Stephen Gaghan who also wrote the screenplay based on a novel, See No Evil, by Robert Baer). I strongly recommend that the next time you and the Captain come ashore, you go and see it or rent a DVD and watch.

It may be a bellwether. The Admiral said we hadn’t seen anything so close to Jacobean tragedy since we saw Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Tragedy several years ago now at the Washington Shakespeare theatre in Arlington. And since he’s read a number of them (and I read through most one year), we agreed we had never read anything so close to the Jacobean spirit before in a post-17th century work. These Jacobean tragedies were blood-and-thunder plays, violent, sexy, filled with regicides and incest, and done between say 1604 and 1692, and they heralded the English civil war to come. A bloodbath like all civil wars. Much destroyed. A king’s head cut off. And then the Cromwell era—a military dictatorship.

Remember what Gramsci wrote:

The old order is dead. The new order cannot yet be born. In this interregnum, a variety of pathological symptoms arises.

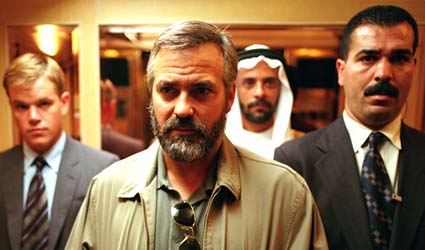

Like a Jacobean tragedy, our hero is a minor player mostly amoral shit whose experiences lead him to be half-crazed: he lives a life of mindless violence amidst the seething court politics of shifting powerful cliques made up mostly of utterly amoral shits whose pious hypocrisies would be funny if the situation did not turn them into sardonic brutal curt ironies. His name is Bob and he is played by George Clooney (also an executive producer of the film):

Bob opens the picture by setting off bombs, blowing up people and buildings galore; at midpoint he is tortured, and he ends the picture by blown up himself—along with the one faint hope for decency in Beirut. Bob dies in the one attempt at a good deed he tries—though he is also trying to put this young man on a throne because he’s now an outsider, would have some revenge this way on the company which acquiesced in his torture, and needs a new clique.

Like a Jacobean tragedy, we have a multiplot design. The plot-design keeps four stories going in parallel structure. (This makes for some difficulty in picking up what’s happening at first.) I’ve just outlined Bob’s. We also have the story of Brian, the young all-American male who works for the oil company and at first thinks it’s a somewhat honorable firm. He’s played by Matt Damon. He provides the happy ending—such as it is. He gets to return home to a wife, Julie (an ultimate stay-at-home-Mom who exists to be politically correct at home, a comfort station, for all, played by Amanda Peet), and their remaining child in the antepenultimate still.

We have the story of Bennett, an African-American man who plays a lawyer who (like Brian) is trying to make a good living by following the minimally respectable rules of the law. He is supposed to advise the company and also keep the US government informed what’s happening abroad and what the company is doing. This will help keep people from behaving too ruthlessly. He discovers he’s an instrument for murder, thuggery, and no-holes-barred fierce aggression and exploitation of whatever comes to hand by one company to force out the others, and then make as much profit as they can without any concern for the people of any country. What he discovers and the people he interacts with (very fat cats who turn into steel robots when at all questioned or crossed), reminded me of a documentary Yvette and I saw last Christmas about Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2003 documentary). It showed (amid much other flagrant lies and stealing as just business) how a stock company simply robbed the people of California egregiously for electricity and got away with it for a long time because they were supported by Bush and his people in high offices across the US and in DC.

A virtuouso rant moment: Tim Blake Nelson as Danny Dalton does a rant about corruption, how corruption runs and rules the world when they encounter one another by the courthouse. Corruption makes the world go round.

Bennett provides a tonic note at the end. Like Brian, he gets to return home. His is a quiet house in DC. His father (played by William Charles Mitchell) is sitting on the steps, a failed alcoholic. Bennett had tried to throw the father out earlier; he had forbidden the father to smoke in his house. Now he gives in. Come on in, Pop. And the door is firmly shut. Shades of a Gorey cartoon where a woman closes the curtain on the window and walks off because the world is disquieting and it’s better not to see.

And we have, finally, the story of Farooq. Played by Sonnell Dadral, we see him first fired from a job with a group of other Muslim engineers and workers. Someone from the company walks up to this miserable site (all steel, the ground all sand, cement and junk, the sky a continual vile kind of grey) and tells them to scram. Get out of here. You have a few days to get your passports in order and then out. He is taken to a school where he is trained in Muslim fundamental ideology and at the same time slowly groomed into taking on a suicidal mission to blow up a ship. We see him in a film where he is telling the others what to do with his body religiously. What body? He blows himself, a cruise missile and an important ship for the company up in the penultimate scene in the film. As the camera headed towards the ship, putting the viewer in the perspective of Farooq as he headed towards this apothesis, we were reliving 9/11 from the standpoint of the Arab men who rammed those planes into the World Trade Center.

Powerful performances by Mark Strong1 as Mussawi (he has a speciality in torture); Christopher Plummer as Dean Whiting (he has the role that unifies the three plots); Chris Cooper as Jimmy Pope (head of Killeen, the one central oil company with whom Connex, another old company, combines); William Hurt as Stan (minor player), and a host of other men, fat US businessmen, Arab emirs and their sons, brothers, uncles, male connections, terrorist trainers, Arab teachers. The very few women were presented as complacent trophies, wives and mothers (when young and thin), very much secondary beings in this world of high luxury provided by male corruption and death. There were two very tough hard women types: one high in the company with pearls at her neck and the discreet black dress or pants suit dismissed individuals at the flick of her cigarette (Susan Allenback, a paralegal [?]); an African-American woman was a hard-ball questioner (who however got nowhere). Extras of all sorts everywhere: I was touched by a believable photo of a poor Arab woman sitting on a filthy stoop by a wall in Palestine.

The movie reminded me of film The Constant Gardener (which I barely did justice to in this blog). Directed by Ferdinand Meirelles, based on the novel of the same name by John Le Carré, starring Ralph Fiennes as Justin Quayle, Rachel Weisz as Tessa, his wife, Arnold Blumh as Hubert Kounde, and Bill Nighy as Sir Bernard Pellegrin, The Constant Gardener exposed drug cartels and the human damage they did. It was more hopeful because, like Munich (Steven Spielberg’s latest film) now also in the theatres, The Constant Gardener had at is center a well-meaning idealistic young man who is turned, twisted, and destroyed, but is a genuine ethically humane man. Ralph Fiennes was a kind of Hamlet who had lost his Ophelia. Munich has a single hero who begins as a very good person and is slowly turned into an assassin and is horrified by what he has become.

No such heroes here. No important consciousness at the center which we explore and care about as an individual. This is Jacobean tragedy. The fat cats (the American capitalists who are last seen feasting at a tuxedo and swank gown (all women bejewelled, all men with cigars) dinner, toasting the slimy, type not fit to run a brother (we are told at one point) who they are putting in charge of the country since they know he will be very cooperative. Bob, our Vindice, could easily have put down a bleeding corpse next to a dying Mellida. I could see Farooq acquiescing to lug a corpse into a closet. Bennett knew before the action began that in the end, he’d walk quietly home, having lost even a glimpse of ethical control. The moral of his story was: "Anything for a quiet life?" And Brian. He’s out of a job but another will come along. A minor courtier player, an Antonio trying to find some emotional comfort with his vulnerable passive Mellida.

As with Jacobean tragedy, it wasn’t always easy to figure out what was happening and to keep things straight. Madness and chaos and non-meaning emerge when you switch (as if you had a remote in your hand) from story to story, character to character (and there were so many).

The Admiral said the audience didn’t appear pleased with the movie. They left quickly. The costumes, the filming, the shots, all true to life—on locations I could recognize, in clothes Caroline said she sees people who run ritzy-parties wear. Could it be this audience identified with those fat cats? Caroline thought so and Rob concurred. But I and they weren’t there, except by implication, though yes we live off oil and our lifestyle is partly dependent on squeezing millions of others, and we do nothing about the powerful cliques of people (called nations with their militaries and laws on their side) who keep so many in abysmal poverty and kill to do it. I don’t have an SUV but live comfortably and my small car uses gas and I have no trouble getting any. Still I don’t identify and think the powerless are not able to do much (the world’s workings is beyond this particular blog). Anyhow I’m not sure that was it (though maybe).

So maybe, could it be that they felt obscurely they had seen as if rising from some sea, an ugly piece of blood-drenched wood, a used-condom, or that fish bowl an American soldier said Iraq was like (it was like shooting fish in a glass bowl). Or perhaps they remembered the crazed look in too many eyes in the film (including that of the torturer), dead babies (Brian’s son is electricuted by mistake in a hotel pool), poor women in black sitting on stoops in bleak compounds Palestine, ruined landscapes, endless highways, and the shadow of the guillotine in those heavy weapons the men every once in a while would lovingly show to one another (lying in a suitcase). They had been forced to look at these things in all their grim prophecy as the sardonic multi-plot hurried on.

Or do you think it is rather Gothic film? It lacks the melancholy of film noir and is too amoral to be pessimistic. Nothing metaphysical. No God or supernatural anywhere to be found (except in the delusions of Farooq and his compatriots and seducers). No gothic heroine, sensitive and lost, the ultimate victim. Hardly any sex in fact. Besides where is the sense of a past? Perhaps the stills of Palestine? Casablanca now a dull hole of bare streets? Nonetheless, perhaps you would like to make an argument for this once you’ve seen it and have time to write back.

Be careful at sea, my dear.

Sophie

1 Once upon a time Strong was Mr Knightly in the BBC Emma: in the choice of Mr Knightly,film-makers chose to give added macho male or sexual dimensions to the folktype they wanted: in the BBC film with sweet Kate Beckinsale, Strong, an actor with a hard face and psychological baggage; in the A&E with the sexual virgin princess type, invulnerable Diana, Gweneth Paltrow, Jeremy Northam, an actor with sexual feline alluringness and a gay subtext. See Two of Many Emmas.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Caroline wrote in to say:

actually, that’s a great picture…it has matt damon and the decent son, nassir, who gets passed over for the crown because the americans don’t approve of him all in the elevator together when clooney is working to have nassir assainated, before he gets screwed over…

and syriana is a code name in the american gov’ment for an oil rich

country….usually one where covert ops are being performed…

L.C.M.

— Chava Dec 27, 9:35am # - Now you’ve mentioned Lynn Paltrow’s first cousin.

— bob Dec 27, 8:47pm # - Dear Bob,

Have I? Who is Lynn Paltrow’s first cousin? Come to that, who is Lynn Paltrow? I guess a relation of Gweneth so perhaps you are referring to Gweneth?

Cheers to you,

P.S. I’m attending the MLA these few days as it’s in DC, a subway ride away.

Chava

— Chava Dec 27, 10:49pm # - Ellen, you mentioned

A virtuouso rant moment: Tim Blake Nelson as Danny Dalton does a rant about corruption, how corruption runs and rules the world when they encounter one another by the courthouse. Corruption makes the world go round.

Actually—and this makes it all the more a Jacobean pot-boiler—part of the rant was that corruption is what makes us all warm and comfy here in America. That’s what Vindice loves and hates, and it is the two brothers in The Duchess of Malfi who are like "two plum trees, that grow crooked over standing pools… rich, and o’erladen with fruit, but none but crows, pies, and caterpillars feed on them" as Bosola tells us.

Thanks for pointing out the parallel!

Cheers,

Joel Davis

— Joel Davis Jan 10, 4:09pm #

commenting closed for this article