Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Women Weave Webs, but men invent, name & control technology · 8 February 06

Dear Gudrun,

I like your opener: WomenWeaveWebs. It reminds me of how in both Danielle Ofri’s Singular Intimacies: Becoming a Doctor at Bellevue and Perri Klass’s A Not Entirely Benign Procedure, both women doctors point out that women have been sewing for centuries, but that when it came to training people to be surgeons, men were trained, and that until today men dominate the fields of major and minor surgery except in the case of childbirth.

Upon participating in her first operation, Perri suddenly realizes

why "very complex suture maneuver is "a regular old blanket

stitch:"

"Surgery is supposed to be supermacho, of course, so they have tried to elevate sewing into the realm of aerospace engineering, and if a woman seems to pick it up quickly, they mutter to each other that of course a women have such small fingers. Many male surgeons want to be proud of their sewing in the manner of an expert laying complex circuitry, not a seamstress showing off her quilt, so why make trouble? ... one surprise of surgery is that a great deal of it is much more crude than you imagined. This is not necessarily a criticism; it’s just that people tend to imagine mystic processes, remarkable instruments … (pp. 94-95)

when what you do as an alternate to sewing is staple. And it’s a real stapler.

Words: womp. It sounds like a reverse of pow. It’s a slang verb in doctoring, says Klass:

"’We’ll get him on the table, and whomp out his gall bladder,

and while we’re in there, maybe we’ll womp out a piece

of his bowel …’"

One way in which women have been cut off from proficiency in the Net is the choice of language. It reminds me of the way words are used on highways to give directions, only it’s worse since the jargon tends to violence (kill, bash), anacronyms, and strained uses of verbs so that what is generalized in the word is not what you are doing (type this in here), but what the trained engineer thinks he has to do with his technology in response to your typing. Not your gesture ("on"—as in turn this on), but what is provided by some remote machine ("power").

Women are rendered helpless by the language men have invented to make instructions. And then are seen as helpless.

Again concrete and picture thinking is presented as inferior. Women are encouraged to be literary, imaginative, and do work through examples. Claude Levi-Strauss associated this with the savage mind and called it bricolage. Richard Feynman is not ashamed to say he thinks through working out concrete counter examples.

The metaphor of sewing is used to put women in their place. It’s

a ceaseless activity on behalf of others which makes them sit in one place. Penelope is the great exemplar—who waited for a decade for her man to come home, every night unweaving what she wove in the day. Again Klass picks this up: when Lytton Strachey came to describe Florence Nightingale he used the metaphor for a sardonic twist where the ability to sew as central to doctoring is turned into a nasty lust for power when it’s a woman who does it:

"Why, as a child in the nursery, when her sister had shown a healthy pleasure in tearing her dolls to pieces, had she shown an almost morbid one in sewing them up agan (Lytton Strachey, "Florence Nightingale," Eminent Victorians," quoted by Klass, p. 53 as an epigraph).

Sewing was indeed in the period a weapon to repress women by—and also to force them to consume their time doing. There was so much of it. Jane Austen yearns for a dress she can buy off a rack (she imagines this as heaven). She sat and sewed her brothers’ shirts; the family biographies and cult go on about her satin stitch, but it’s her books that kept her alive—when she had time to write them.

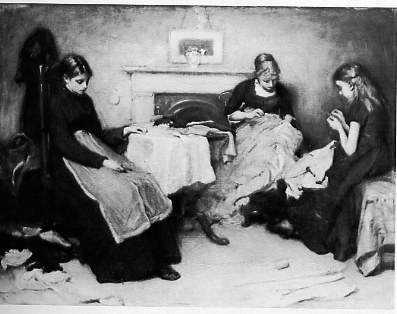

The reality of the woman’s life who sewed for a living is here pictured by Frank Holl (1845-1888):

The Song of the Shirt (mid-19th century)

The allusion is to the famous ballad by Thomas Hood. Underpaid, overworked, and undervalued—Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton is a seamstress.

But in 19th century text after text milliners and seamstresses are labelled "grisettes," "loose," connected through ridicule and shame to prostitutes which in the mythology of the 19th century were fair game for gentlemen because they were such man-trapping creatures.

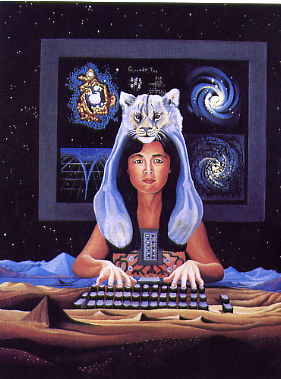

So when Donna Haraway (Simians, Cyborgs, and Women) wants us to imagine her cyberspace woman, she invents a science fiction term, like Cyborg, and clothes her woman in SuperWoman cartoon imagery with a cat that is more than half-tiger as her crown and long hair:

Cyborg by Lynn Randolph

I wasn’t specific in my earlier letter when I talked of how women are driven to ‘safe’ or secluded (women-only or women-controlled space) places on the Web. In her "Gender Differences in Computer-Mediated Communications: Bringing Familiar Baggage to the New Frontier" (note that cowboy term, frontier), Susan Herring shows how men are assumed to and do behave differently in cyberspace, manifest different values; in Nattering on the Net Dale Spender is brave when she defends women-only lists as the only places where certain kinds of conversations will be allowed. On a mostly women’s list I’m on one woman today grew irritated when another woman was complaining after a man was unduly aggressive at yet a third women. "We should perhaps have a woman-only space." Another had been sneering at "whiners" and yet another wrote she certainly didn’t need this "protection" and denied there was a difference between men and women’s styles on the Net.

An issue that is brought up repeatedly in feminist writing on cyberspace is the need to make the experience safe for women1. The word "safe" occurs over and over again from the most militant and abstract, modernist writers (Sherry Turkle, Life on the Screen and Donna Haraway) to frankly solicitious and openly politicized feminist academicians (Jill Arnold and Hugh Miller, " Academic masters, mistresses and apprentices: gender and power in the real world of the web," and Cheris Kramarae "Technology Policy, Gender, and Cyberspace") and to cyberfeminist Mari Kibby who shows "Babes on the Web" encourages debasement and ridicule and ultimately violence against women.

Photos people noticed in cyberspace that can be counted show how in cyberspace women are treated primarily as bodies to be bought, sold, traded, and also mocked. Men frequently use jokey pictures of themselves and will feature photos of themselves relaxed in non- professional life in activities associated with males (e.g., fishing) and in gender-inflected clothes (two men in one study presented themselves in "a baseball cap backwards"). Women include few photos; when they do have some, these tend to be plain or institutional mug shots. In one study to find a photo of a woman in a non-professional pose, the author had to keep clicking to find buried ("embedded") a photo of one woman kissing her baby, or in another a case a woman "documenting my first batch of home-made pasta."

Why have photos at all? Every study I read argued website is "a social hypertext" which both builder and visitor understand as projecting an identity, and it is felt to be unnatural not to put a face to the name. Individuals are often asked to provide a photo, even in those university-controlled spaces where their identity (men and women) is presented as exchangeable or fungible.

Gail Hawisher and Patricia Sullivan’s "Fleeting Images: Women Visually Writing the Web," show that across the board (should I say loom?) images of women function as advertisements or bodies and objects to be bartered; the representation of women is usually chosen and controlled by someone else. This is as true of academic women as women in commercial advertisements. One difference for academic and professional women is they work hard to de-sexualize themselves, and the result is homogenized and normalizing depictions (regimented is Susan Bordo’s term in her Unbearable Weight) reminiscent of junior high school yearbooks.

All this is true of the photos I chose. There I am in a white blouse, thin chain necklace, and thin black jumper sweater with white pearl buttons (see left hand column above), or as a mother (with glasses on or unstyled hair) inside a family group in the "More about" section of the website2.

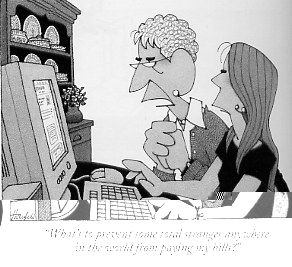

I looked over how the New Yorker cartoons over the last 4 years showed computers in the book version of the history (where you have 2000 selected cartoons from the 64000 plus). I found women not men were shown at computers. (In contrast somewhat younger men were shown on cell phones walking in the open.) The women were all middle-aged. In one cartoon we see a well-dressed woman of "d’un certain âge" engrossed in shopping; in another we see one drawn similarly showing a comical anxiety over money which suggests (as in the early 1920s cartoons women still don’t understand technology, money and human nature) as she is taught by her daughter:

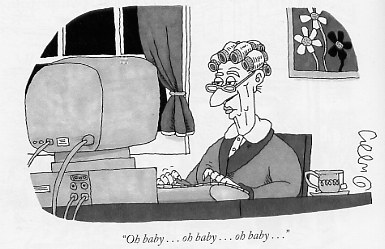

The third is an old woman made to look as the last thing any man would want who is dreaming of sex:

Not a denigrating stereotype is overlooked: long nose, glasses, curlers, high-buttoned collar, tight mouth with lipstick. Women cannot only not escape their bodies. They don’t want to, even when no man could possibly want them.

I saw a nasty cartoon on a T-shirt in a local store the other day: we see a very ugly very old woman sitting alone on a dismal-looking park bench, and the caption records her "boast" that she wouldn’t marry just anyone. A comparable mockery of an African-American or Native American or even Arab-American would draw upon that store-owner explict continual outraged ire.

I think we don’t hear of the world wide web as a vast epistolary novel because letters are associated with women and are womanly.

Sylvia

1 PS. See Susan Herring’s "Searching for Safety Online: Managing Trolling in a Feminist Forum," CSI Working Paper

2 PPS. The small black-and-white photos were chosen by Jim as his favorites at the time. I was in my mid-40s.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Chava,

Fascinating reflections about the web and communication patterns. I was struck by the final comment that we don’t consider the internet a vast epistolary novel because letters are womanly.

In many ways I think of the web as womanly or feminine because it is designed to be relational and expose connections where they haven’t been seen previously. I think that is a way that many women in general like to relate to the world. (As opposed to the masculinist approach which is to seek information in pursuit of a particular goal – an interesting test of this would be to look at google search results. The premium at google is to deliver the desired result in the first position, but there is interest for people in the second, third, and fourth pages of results. I think that there may be a gender correlation.)

The web exposes these relationships among information and ideas and between people. The "killer apps" of the web have been things that connect people: IM, ICQ, friendster, MySpace. I don’t use all of these but even with technology mitigating it, people seek connections with other people.

What about ideas though? I think that is the space where the internet has offered the greatest potential to build ideas collaboratively, but I don’t believe that potential has been realized. Collaborating online, building ideas, is still fraught with challenges as you outline about the Trollop-l and we see it on WOM-PO. Part of it is the disjointedness of time, but there is something else a foot as well. Perhaps it is time and the amount of time that people devote to thinking and communicating online. Perhaps it is the vast possibilities that dwarf people’s ability to take action.

One of the areas where I think information (not ideas, yet, but the potential exists) is really built in new and interesting ways is Wikipedia. I’d love to see someone invest in building that repository of information from a feminist perspective. As I have been reflecting on the recent passings of prominent feminists (King, Wasserstein, and Friedan) and the one last year that I am still mourning – Andrea Dworkin – it makes me realize that public community histories of our work with contemporary interpretations are really important.

None of this necessarily relevant to your post or your project, but the thoughts that I had in reading your thoughtful posts.

All the best,

Julie

PS OK, one thing I don’t understand about your blog are the addresses and signatures. Can you explain to me? Or is it posted somewhere?

— Julie R. Enszer Feb 8, 9:22pm # - Oh, and I forgot, you have to look at Wickedary. It is Mary Daly’s book from the 80s (?) that is a dictionary woven with a radical feminist sensibility. Very relevant and pre www.

http://cat.nyu.edu/wickedary/

Julie

— Julie R. Enszer Feb 8, 9:24pm # - When I read the title, I started singing and humming Ella Fitzgerald’s Detour Ahead, "The farther you travel the harder to unravel the web she spins around you." Did you read my e-mail about Ella Fitzgerald?

That’s all I’m going to say right now and probably all I’m going to say for the next few days, because I’m busy with school.

— Jennica Feb 9, 8:03am # - From someone on Wompo:

What came to mind deeply was this . . .

FROM ADRIENNE RICH:

"Vision begins to happen in such a life / as if a woman quietly walked away / from the argument and jargon in a room / and sitting down in the kitchen, began turning in her lap / bits of yarn, calico and velvet scraps, / laying them out absently on the scrubbed boards / in the lamplight, with small rainbow- colored shells . . . / Such a composition has nothing to do with eternity, / the striving for greatness, brilliance— / only with the musing of a mind / one with her body, experienced fingers quietly pushing / dark against bright; silk against roughness, / putting the tenets of a life together / with no mere will to mastery, / only care . . ."

This Adrienne Rich citation about women and sewing opens a monument of classic feminist theology by

Elizabeth A. Johnson titled :

She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discoure

Not just wonder upon wonder for Rich but also for Johnson who chose it to begin her great book … ...

Sarah

— Chava Feb 9, 9:04am # - Dear Harriet,

From Rosemary on Wompo who sent along more lines from the same poem in which Adrienne Rich’s "Vision seems to happen" occurs:

I’m now told this is a concluding passage in a long poem called "Transcendental Etudes" It appears in The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems Seelcted and New, 1950-1984.

Another passage:

No one ever told us we had to study our lives, / make of our lives a study, as if learning natural history / music, that we should begin / with the simple exercises first / and slowly go on trying / the hard ones, practicing till strength / and accuracy became one with the daring / to leap into transcendence, take the chance / of breaking down the wild arpeggio /or faulting the full sentence of the fugue.— /And in fact we can’t live like that: we take on /everything at once before we’ve even begun / to read or mark time, we’re forced to begin / in the midst of the hard movement, / the one already sounding as we are born.

Rosemary said the title of the whole poem is "Transendental Etude," and I discovered the title of the book in which it appeared, The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems Selected and New, 1950-84 on a site dedicated to helping women accustom themselves to, understand, and effetively use technology on their own with their own needs in mind.

Sylvia

— Chava Feb 10, 9:58am #

commenting closed for this article