Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Friends with Money (another college friends grown older tale) & more on _The Faith Healer_ · 15 May 06

Dear Anne,

I write to recommend going seeing Nicole Holofcener’s Friends with Money while there’s still time. It’s excellent and is hurting badly because of the lukewarm reviews. These say, ho hum the same old thing and triter. Yes it’s another woman’s movie, but better than Lovely and Amazing and not trite at all. My local "art" movie house (this term seems to mean the owner shows intelligent commercial films) had relegated the film to the smallest showing room and twice a day. The owner has had to extend the time to all day long and at the 4:50 pm showing Yvette and I had to sit way up front: the room was so crowded.

Ladies in Lavender played in this movie house all this past summer though it was ignored and dissed by the reviewers. People who provide the money to make films do notice the box office numbers. If we want more films by women, we have to support them, even if the actresses are superthin types, and thus I write this letter to you and send the one photo of the four women together I could find on the Net:

The trope is the familiar one of the group of college friends who have not lost contact because they live in the same area, and have (more or less) begun to live the same sorts of lives. Jim suggested there is a certain amount of myth in this trope: how many tight groups of college friends do keep in sufficient contact and lead sufficiently similar lives to find support from one another? Perhaps a few, those who go to NY or LA (this film is set in California) or some city where there are enough niches to fill.

Mary McCarthy’s The Group was a novel using this trope; a film showing the reunion of a group of older adults who had lived through the Vietnam era is another.

The anomaly and plot device here is one of the four women has not done as well: Olivia (Jennifer Aniston) is a "maid" or cleaning woman. We are told she taught in an expensive private school where the students arrived in Jaguars, but she loathed it, and now has been reduced to cleaning houses. We first see her hands cleaning a house in the quick efficient way cleaning women in teams learn to: I’ve seen this as for a short while I hired such a team. (I was so ashamed of the way they were treated, how they were berated and looked that I soon stopped.)

Then we switch to a dinner. The film opens and closes on a dinner scene. The four women friends, Olivia, Jane (Frances McDormand), Franny (Joan Cusack) and Christine (Catherine Keeler) are dining out together. As the film opens, three have husbands, and we quickly see that Franny’s Matt (Greg Germaine) makes a lot of money; Jane’s Aaron (Simon McBurney) is needled because he is "accused" of being gay (he does not conform to macho male ideals at all), and it’s she who makes the large sums because she produces expensive designer clothing; and Christine and her husband, David (Jason Isaacs) make money as co-writers of movie scripts and fight bitterly continually. Olivia is alone. As the film closes, Jane is still with Aaron and Franny with Matt, but Christine and David have broken up, and Olivia has a new boyfriend, Marty (Bob Stephenson), a man we know nothing of but that he lives in a "dump," doesn’t shave very often, is chubby, wears a very expensive chasmere jacket, and like the other male in the story Olivia goes to bed with has bullied Olivia over her cleaning job: he hired her and insisted on paying her $50 for a whole day’s work when she wanted $65.

The movie works as a multiplot—like Syriana except that instead of a quest plot which culminates in a climax, we have an episodic cyclical patterning. The film ends with a series of small and ironic triumphs. Jane begins to wash her hair again; Christine is now selling her house and having to make a new life for herself; and Olivia has been abandoned by the cruel jock alpha male Franny was wrong to send to her and herself given up cleaing; she’s with Marty, the somewhat kinder male partner in casmere whom I described just above: we are not sure how kind he is; he says he has money and does not need to work, but there’s a lot of lying going on. Franny requires no change.

What’s superb are the many vignettes where the characters interact in ways that are deeply redolent of real life. Snatches of dialogues, situations (in Old Navy on a line; in a restaurant; in a bar; the movies; at home watching TV, eating and shopping) have an uncanny way of imitating daily life. It’s a woman’s picture or l’ecriture-femme as film because of the typical content and mood, not vatic, nothing driving towards a climax and no moment when once ignored lost forever.

I recognized myself in Olivia. The painful quiet gasps in the audience when she allowed herself to be not just driven down on her price, but a shit male, Mike (Scott McCann) demanded money and gifts from her when he had accompanied her cleaning but had done very little reminded me of my behavior when I was in my later teens and very early 20s. I became reclusive and avoided people because I could not trust myself not to give in to such ruthless heartless humiliating pressure. Olivia keeps courting punishment and we are not sure at the end she has found a decent person to be with. Each time she gives in it’s slow and we watch her consider and then crumble. She can’t resist trying to hold on. Holofcener leaves the audience enough time to hope she’ll hold out and yet she never does. Yet she’s not despised nor at all different from the others that we can tell. Except that tell-tale job. And her poverty. Psychiatrists don’t help, Anne. To be with others is to be used and pressured, especially when the other is a certain kind of abrasive male (or tenacious alpha female). The last dialogue between her and her new boyfriend leaves us uncertain whether she’s found safety as yet.

The angry woman is Jane. She explodes continually, and makes scenes and quarrels because she’s disrespected—mostly because she’s getting old and is responded to by others as someone they don’t want around and whose existence they cannot see any need for. People get in front of her in line and she can’t get anyone to be on her side. The themes of her story connect to Olivia’s, for unlike Olivia, Jane has found safety: Aaron is the kindest and gentlest of human beings. Alas, though, she’s bored; she half-despises him for much of the film. She can’t sympathize with his anxiety whether he looks right. These feelings emerge in her lack of interest in sex with Aaron, her husband, who may just have some gay impulses, but is not going to act on them. She’s having a hard time accepting her aging. Yet it’s he who who compliments her. He alone who suddenly says to her her hair looks awful and she must wash it, and in response she at long last does. And ironically, Jane’s pleasure in life is dressing other people up in socially desirable playful costum-y clothes. Like those in the still I’ve sent you.

Christine spends the film making ill-natured remarks which if heard could hurt the others. She’s trying to get back at the world, find some release for her own hurt. Her husband, David, continually insults her, talks down to her, and thinks she should not be hurt, for what do words mean? She can find no space to be free in. Subject to her neighbors too. They ave a small son whose demands make occasions for more quarrels: the boy wants an Xmas tree; the husband hates the exorbitant price, and so does Christine, but she wants to please the child.

We can link the themes of Christine’s story to Olivia and Jane, for Christine’s remarks are aimed at Aaron. It’s ill-natured and endangers his status for her to say so often (as she does) he’s gay. She gets back through him because she instinctively recognizes in him vulnerability. In fact in David she married a man with as cruel a tongue as hers.

Franny is the rich lady who refuses a loan to Olivia. First Olivia must somehow "prove" herself. Gee thanks says Olivia. To which Franny doesn’t say, "I can make these demands you know," but rather the money is also David’s. Hypocrite. It’s she who sets up the blind date with Mike, the abrasive male who continually takes advantage of Olivia from the moment they begin going out together.

Unfairly, but not unexpectedly, Franny has the most comfortable relationship and life. She’s a winner. How is this, the film asks? The answer seems to be chance and Franny’s eye for picking a money-making self-assured male. And not being taken advantage of.

The film is comic though. Life bumps along. And importantly, it’s not quirkly in the way of Lovely and Amazing which had people at the center (e.g., a very heavy set older woman who has adopted an African-American girl and undergoes cosmetic surgery during the film) who do not seem common types. Lovely and Amazing did not make the men important elements in the stories of the women. The types in Friends with Money are not only persuasively central. We see a redefinition from a humane point of view of women’s subjective experience apart from their role in the men’s lives. The men impinge and can provide money, but they are an important element in the women’s perspective on themselves. Their salaries provide the wherewithal to live—and avoid becoming a cleaning woman or have to take an intolerable niche.

As the film ended, I heard a woman behind me saying she had never seen a film like this. She was intrigued. Next to me Yvette had watched while intensely engaged.

Don’t miss it. I looked up Holofcener and discovered she’s written scripts for Sex and the City. This film is better than that; it’s not a soap opera: it has no melodrama and over-the-top emotion, and we do not have women presented as primarily on the hunt for males and therefore rivals for them. The women are friends, three of whom have access to money at the film’s start.

I’m just now returned to reading novels by women for women of the l’ecriture-femme type. How I’ve missed it. This term has been hectic with the literature of science books, with writing papers for conferences, reviews, and keeping up with lists. Trollope-l seems again dying. I had thought I’d start listening to The Small House at Allington when I finish Ayala’s Angel: my idea was to join in with the people there, but now that no one is materializing I’m not so sure. I have a set of audiocassettes of Carol Shield’s Unless read aloud by Joan Allen beckoning me.

I hope to find time for more true sustenance in the evenings and when we go away too. I’ve just finished Frances Hodgson Burnett’s That Lass O’Lowrie which I’ll write about tomorrow evening. I’m returned to Anne Murray, Lady Halkett for one hour each day. I’ve just begun Sibilla Aleramo’s Una Donna too. And I bought a book of the writings of an eighteenth century American woman, one I learned of at Montreal: Judith Sargent Murray who writes of Anne Murray, Lady Halkett.

Yes I know I’ll be teaching, but I’ve read all the books (Including Dava Sobel’s Longitude), and I’ll try hard to keep the teaching work in a tightly controlled round.

For now at long last, this evening: Anne Tyler’s Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant.

I can hear Celtic bagpipes playing in Yvette’s room. It’s an MP3. How I love Irish music (as well as plays).

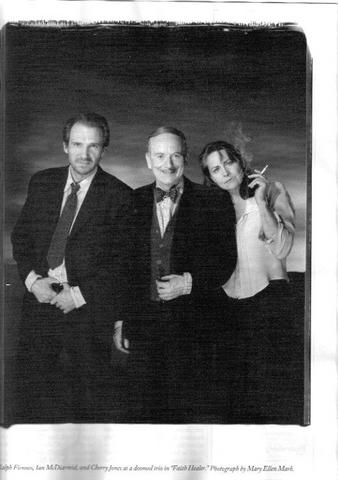

Ah, an excellent review by John Lahr of Brian Friel’s Faith Healer in the New Yorker last week: "Crisis of Faith". Lahr characterized Fiennes thus: "As Frank, Fiennes is outstanding. He exudes a natural, reticent magnetism; gaunt and thin, his sensitive features belie a fierce heart." He forgot to mention Fiennes’s quiet dignity and left out Cherry Jones altogether: a despairing brooding alcoholic, gentle. Anne, I did read the play itself since seeing it: I found it in our library: it seemed to include in it a metaphysical perception of life melancholy and anguishedly true, one which was yet painfully dignified and comic somehow, very like Beckett. I know the trope of the college friends staying together is not probable; flotsam and jetsam, fragments of chance. But it enables Holofcener to present women’s subjectivity; here the view is from the male side, and the angle is what he is driven to do for a living, to support the others and his own barely held-together manliness.

Our weather here is beautiful just now, sunny, bright, cool air still, lots of breezes, and shadows in the brightness. Dappled. I hope you are well.

Sophie

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- If you like Celtic music, do you want me to e-mail you my favorite Celtic song?

— Jennica May 16, 1:25pm # - Dear Jennica,

Yes please do. Jim says you would send it by attachment and I would put my speakers on. I have hardly ever used the sound mechanism of my computer :)

I hope you got the photos I sent you and saw the photos of the May Day celebration I put on my website.

Sophie

— chava May 16, 2:42pm # - I sent the song to your ellen.moody@gmail.com e-mail address. I’m listening to the song for the second time today because I like it so much! I did see the photos. My mom saw them too.

— Jennica May 17, 6:00pm # - Dear Jennica,

I don’t know why but I’m having trouble reaching my gmail and can’t access the song. I’ll try again tomorrow. If I can’t, could you send it to Ellen2@JimandEllen.org?

The Admiral and I will be away for late Thursday and all day Friday, back on Saturday. We go to a conference on Intellectual Property Rights in cyberspace. Yvette holds the "fort" down.

Glad your mother liked the photos. I lost the envelope with the reproductions of the paintings we saw in Panell so was not able to put them up too.

Adieu, Sophie

— chava May 17, 10:23pm # - Loved Friends With Money. Sat through Faith Healer because Kathleen loves Ralph Fiennes and would probably run off with him. The play desperately needed somebody’s blue pencil – as an Irishman who loves to gab, I know what I’m talking about.

But as to groups of college friends (women particularly) staying in touch in New York, I can assure you that this is not a myth. My daughter, at 33, has just emerged from a cocoon of such friends – not that they’ve lost touch by any means! – and my nephew’s girlfriend, more recently out of Bryn Mawr, is totally grounded in school groups. She’s still intimate with classmates from Sacred Heart in New Orleans! The group, in short, persists.

— R J Keefe May 18, 10:35am # - Dear RJ,

Thank you for commenting. As you can see from what I wrote about Faith Healer, I’m another woman who find Ralph Fiennes an very appealing male presence to dream about.

Jim suggested that it is possible some college friends stick together and form a support group, but he thought it would only happen if the friends stayed more or less in the same socioeconomic group and lived not too far apart.

These all-women’s school foster these groups too. It’s an important part of the experience. Yvette would say that at Sweet Briar sometimes it felt like there was one big sorority for each year.

Sophie

— chava May 20, 1:04pm #

commenting closed for this article