Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Women's life-writing: prose and poetry · 28 May 06

Dear Lady Mary,

I am in turn very moved by what you wrote, and think what you say about women’s retirement (or retreat) and friendship poetry and their lives can be a key to interpreting plot-designs in women’s autobiographies.

As you know I’ve been slowly putting on line Anne Murray, Lady Halkett’s story of her life. This remarkable memoir has been mostly ignored because people today reading it can’t think of how to treat it except as a love story. The events that leap out at modern eyes are:

She is courted by an upper class male whose parents have little money; his parents object to her as a wife for him because although courtiers with salaries and gentry, the Murrays have no money; her mother berates her as amoral (and probably also calls her a slut) because the mother does not want to lose her own chits with this family; Anne endures all this calumny and the young man (in effect) stalking her, only to have him succumb to marrying the rich woman his family picked out.

Left alone after her mother’s death (with a small legacy she must wrest from the courts and a need to find someone to live with), her favored beloved brother, Will, ejected from court because of intrigues, she attempts to make her way on her own in life somehow or other. Times being what they were, she finds herself solicited by a spy to help the royalists disguise James, Duke of York, and enable him to escape. This man, a Colonel Bampfield lies to her: he tells her his wife is dead, and although there is no passage in the extant document confirming this, she bethroths herself to him, possibly in the present tense, which would mean they were married (contracted). She quickly discovers that others say (and possibly it’s true she knows) that the man’s wife is still living.

After many pages and other adventures (usually ignored in the retellings), she is courted by a respectable Scots royalist, Sir James Halkett, very well-connected, a propertied man with strong alliances among the Stuarts; he manages to produce indisputable evidence Bampfield was previously married so her bethrothal is no contract and she is free to marry Halkett. After much anguish and stress and pressure from Halkett, and despite profound shame and guilt (my guess is she did consummate with Bampfield), she marries Haklett and has been thought to have presumably lived more or less contentedly with him as his wife until he died (ever after as the story is told, for her thirty years of widowhood are usually omitted as somehow or other not counting).

What’s left out? How Anne Murray struggled to find places to live as an independent woman: repeatedly she becomes an aristocratic respectably married woman’s companion, sometimes for years, but ever working against her loss of reputation and respect, and sometimes treated badly by those who intrigue against her. How first as Anne Murray and then as Lady Halkett acts effectively as a self-taught physician and nurse who nurses wounded men after battles more than once. How (very much in Scarlett O’Hara’s vein if you’ve read that underrated southern masterpiece, Gone with the Wind) she puts herself forward to save the women and people she’s with when they are threatened by marauding soldiers. How (reminding me of Anne Elliot in first and second parts of Persuasion when Anne twice stays behind to pack and arrange the household), as Anne Murray, she stayed behind in a house owned by a Scots lord, and his wife after having saved them from capture and proceeds to rescue their books! How first as Anne Murray and then as Lady Halkett, she worked to achieve respect from those she was surrounded by and often dependent upon, and in the end of the book begins to influence a position for Halkett himself.

Further, her story is further an apology, a justification for herself to her son and to the outer world which had probably bad-mouthed her badly. Sir James’s children, particularly his elder son, did not provide her with the wherewithal to live, and she supported herself by teaching. She may have been influenced by the Frenchwomens’ memoirs of the era (Hortense and Marie Mancini’s books came out around the time it’s thought the then Anne Halkett wrote the manuscript, e.g., the 1670s). Her text conforms to the criteria found in many women’s memoirs from the later 17th through 18th century I heard described in a paper given at Montreal this past March: Caroline Brashears’s "The Female Appeal in Great Britain, 1676-126". Anne Halkett is appealing to her community to understand, to forgive, and to respect her and doing it in just the way other women of her era did, a pattern not recognized since we are not treating these women as subjects, but objects in masculine-derived perspectives (usually suspicious, distrustful, condemnatory with the women seen simply as wives, mistresses, mothers, not in themselves and with one another).

More, and this is where your comments seems to me important and useful. You wrote:

"for me the wishful certitude that one can ‘change anything’ or ‘do anything you put your mind to’ is, however encouraging in intent, false. I’ve battered myself against the wall of impossibilities before: again and again. One cannot stop making the best of what exists, but much lies beyond our control. Poems and artistic genres that recognize this and focus on creating and manipulating the interior circumstances and fashioning, as you say, ‘a hard-won and deeply virtuous contentment,’ matter profoundly to me. More yet, in recognizing and honoring those aspects which we do control – at least in some measure – they relieve the stigma of our lives’ unimportance, of small choices not mattering, of failure if we cannot change great or outward things."

This is what Anne Halkett is doing. She does batter herself against walls of impossibilities, not only in trying to escape (she can’t make up her mind whether openly to disbelieve Bampfield and thus break with him and herself then appear "ruined") or live up to her "duties" as Bampfield’s wife (she is ever obeying him, turning to him for advice, following suggestions he makes that she connect herself with this or that person). She tries to help her brother Will and ends up responsible for a debt he incurred when he probably deceived a woman either by promising to marry her or contracting himself. She shows herself making the best of what exists: all the incidents where she’s a companion which take up so much of the text count for her. After she wrote her memoir, she spent years writing meditations where she may be seen to be earning that "hard-won and deeply virtuous contentment."

We are terribly hampered in understanding her. Someone (perhaps her, perhaps not) cut the opening framing of the book, cut two pages at the point where the first young man was married off to someone else, two pages written about how she felt when she openly said that she understood Bampfield had a wife and her bethrothal had been ambiguous, and, very importantly, the closing pages which tell us of how her marriage to Sir James turned out. We cannot know that it was contentment. So the kind of understanding your words offer which do make sense of her text do not receive explicit validation in the autobiography. Only they do make sense of it.

And other autobiographies of women which dwell on their non-public supposedly non-achieving (because not done in the marketplaces and courts of the world outside a family group) lives.

To turn back to the poetry, I read further into the book yesterday and the author made an effective contrast between mens’ and womens’ retirement and friendship poems. The two types often melt into one. Though he may address himself to a friend, a retirment poem by a man will often not end by dwelling on his and the man’s friendship but rather their political stance individually and how they may be seen in relation to the power games of the world and the individual poet’s belief about the way the universe

works (by chance, through some providential design, hostilely to what is if not acknowledged to be so most needed by people).

A good example of this is Pope’s poem to the Earl of Oxford when Oxford was released from prison (put there by the people who replaced him in office) and had to retire. I’ll quote just the sort of lines one does not find in women’s poems. Pope insists that Harley will be recognized for his great deeds before he was forced from office, arrrested, shamed, and (insofar as his enemies could pull this off) impoverished:

And sure, if ought below the seats divine

Can touch Immortals, ‘tis a soul like thine:

A soul supreme, in each hard nstance try’d,

Above all pain, all Passion, and all Pride,

The rage of Pow’r, the blast of publick breath,

The lust of Lucre, and the dread of Death.

In vain to desarts thy retreat is made;

The Muse attends thee to the silent shade:

Tis hers, the brave man’s latest steps to trace,

Rejudge his acts and dignify disgrace.

When Int’rest calls off all her sneaking train,

And all th’oblig’d desert, and all the vain;

She waits, or to the scaffold, or the cell,

When the last ling’ring friend has bid farewel.

Ev’n now, she shades thy Ev’ning walk with bays,

(No hireling she, no prostitute to praise)

Ev’n now, observant of the parting ray,

Eyes the calm sun-set of thy various day …

The poet doth protest too much. The origin of all these poems, a famous one by Horace declaring that happiness is to be found in private contentment is much more convincing because Horace genuinely turns away and is puzzled over why others want to live for ambition and power and don’t seek contentment. I’ll send that along to ECW (EighteenthCenturyWorlds) later this week (on our poetry Wednesday).

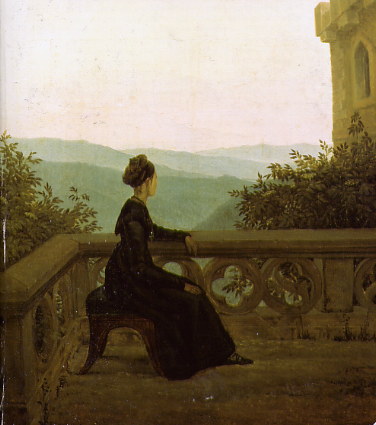

Not that Pope’s poem is not moving; it is so dignified and phrases like "the rage of publick breath" (one feels the heat of lurid scandal-mongering), "Int’rest" calling off "her sneaking train," including that "last ling’ring friend" (so we find ourselves suddenly alone) and then that evocative close which I’ll picture today for us in a painting which was (righly) chosen the cover of a recent Oxford edition of Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho. It captures how the woman can look out to her relationship with nature, God (in the Wordsworthian milieu of this period nature includes God), and her art and friends:

Carl Gustav Carus’s 1824 Woman on a Balcony.

Emma Thompson provides a more cheerful and active-seeming renditon of the trope when she had herself photographed in just the way Cassandra Austen once drew Jane, with the important addition of her sister, a friend (Kate Winslett as Marianne):

We could say that the woman’s autobiography differs from their poetry and resembles more the men’s poetry because they are anxious in the autobiography to apologize, justify, assert the use and value of their lives for the larger society. Their verse is freer (as are their romantic novels, like those of Ann Radcliffe for example), where they can unashamedly create the counter-universes we have been talking about.

Perhaps (ah!) they were freed to do this because they didn’t expect to publish. The expectation that their work would not reach a larger public freed earlier women to write what the drive for a published text, wide audience, and profit and fame today prevents. Here on the Net (as I suggested in a letter to Harriet I called Cyberspace & Attics), we do find a writing experience analogous to that older one where women wrote to a few friends and they constructed a life where their freedom was their time and equality before those they conversed with.

"Mine author" says over and over that for women in the 18th century poetry was a form of life-writing. I’ve thought that the romances of the period were life-writing too, no matter how extravagant, gothic, sentimental or fantastic they may seem, and yesterday reading Anna Barbauld’s essays on Charlotte Smith’s poetry and novels, Burney’s and Radcliffe’s novels, and one tale by Maria Edgeworth I could see Barbauld simply assumed this though writing in the same generalizing spirit as Walter Scott when he wrote his equally perceptive essays on the women novelists of their era (and happily included Austen).

I’ve gone on way too long as usual. I meant to tell you that I watched the second half of Elizabeth I last night, and again found glimpses of an attempt to create a different icon out of the famous queen, one of a woman as finally an alone silent survivor. Today Yvette and I go to see a film adaptation of an Elizabeth Taylor novel, Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont (screenplay Ruth Sacks, directed by Dan Ireland). Taylor’s novel actually has that title and was recently reprinted by Viking. I’ve also joined the Gym and Pool ("Fitness and Acquatic Center) at GMU and "brought in" Jim, Caroline, and Yvette and we are to go swimming and exercising first thing tomorrow morning.

I do hope you are enjoying this early summer beautiful weather and our reading books together on WomenWriters and EighteenthCenturyWorlds. We see in Burney’s Cecilia the difficulty in the real world (and heroism) of trying to create the alternative or counter universe.

Love to Charles and the children. I haven’t written Harriet in a while and will do so soon,

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- This is all very interesting, but I want to focus on the two pictures, as they provide a good contrast between German and English romanticism. Carus’s wonderful painting looks at nature from far above, from the balcony of a very impressive castle, while the photo from the English film situates the two women on the grass, near more or less ordinary houses. What do you think?

— bob May 28, 11:42am # - Dear Bob,

I’ve corroboration that the German pattern distances in order to idealize: in one of the Montreal sessions a woman gave a paper on C. D. Friedrich’s sublime haunted landscapes. In many of Friedrich’s paintings a central woman figure becomes a site where new attitudes towards nature and ironical undermining of upper class romanticisms are pictured.

In the later part of his career he drew peasant women from up close.

Here’s the URL for the blog on that session:

http://server4.moody.cx/index.php?id=421

English artists are not unusual in using distancing, formality, manners to control what’s shown. They do tend to show a person’s head where the person is looking at him or herself within. Perhaps this begins around the time Gilpin gets to be so popular.

Here’s an Italian book illustrator who does not turn the woman’s face away, but she is also looking within and into a disance:

http://www.jimandellen.org/Assassini.jpg

This was the cover illustration to a 19th century edition of a translated text from Radcliffe. Elinor

— chava May 28, 9:25pm # - What I was getting at was that English Romantics (Wordsworth & Keats especially) domesticated Nature, brought it closer to he human spirit, while the Germans used it as a distant, mysterious ideal, a difference that’s expressed in your two pictures. I suppose Shelley and Goethe did both.

— bob May 28, 10:06pm # - Swimming sounds good. I wanted to swim in a lake today, but the closest lake is 30 min away, so we went to the ocean instead, which is only 5 min away. I wish there was a lake where I live. I should go to the pool tomorrow. I often like swimming more than walking for exercise. It is hard for me to get motivated to go to the pool, but once I am in the pool I like swimming.

The other thing I did today was go to a surprise birthday party for a girl in my brother’s choir. She turned 16. Not today; her birthday was an earlier day. I listened to a group of people play jazz; there was an electric guitar, an electric bass, drums, a saxophone, a trumpet, an electric keyboard, and an upright piano. I sang a solo on one song, but that was the only singing I did. I mean with that group. I also sang a few songs with a few choir members in the backyard around a fire. I talked to several of the choir members, and I’m happy that they include me in their socializing even though I’m not part of their choir. I like them all a lot.

The other thing I did was that the birthday girl’s brother who is in 8th grade, two of his friends, my brother, his girlfriend, another choir memeber, and I played with the slinky that the birthday girl got as a present. We sent it down the stairs and saw who could get it to go all the way down the stairs without stopping. I almost got it one time, and another time it hit a basket that was on the stairs, so it stopped, and the first few times it only went a few stairs or less, because I had never tried it before and I needed to practice. We were cheering when someone got the slinky all the way down the stairs.

You might have had a slinky when you were a child; you were a child in the years that slinkies were popular. It took me a while to figure out the math of when you were a child. I wish I was quicker at math. Maybe the reason my dad is better at math than me is that my generation is more dependent on calculators than his generation. But the real reason is that he is an accountant, so he does math a lot. But I probably could have figured it out faster if I had calculated it an easier way.

— Jennica May 29, 3:10am #

commenting closed for this article