Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Fiercely laconic: gush & spasms in women's poetry and gothic · 8 June 06

Dear Harriet,

I’ve just read an essay by Isobel Armstrong which is probably

important for trying to understand women’s poetry: "The Gush of the Feminine." It appears in Romantic Women Writers: : Voices and Countervoices, edited by Paula Feldman and Theresa Kelley. I don’t understand Armstrong easily when she writes in an allusive style as she does here. It may be said there is no excuse for saying something so insistently through cryptic references to texts, but it may be that there are ideas that cannot be expressed or argued from a text without this kind of generalization hopping. By generalization hopping I mean she does a close reading of a particular text on her own (only included with epitomizing comments), and then proceeds not to dwell on a ext’s literal content but rather the themes and archetypes and details it shares with other texts because the literal content is often misleading when it comes to understanding what the writer wants most deeply to express. Writing is not much different from ordinary speech in this: we see this kind of unconscious and conscious repression in our speech all the time.

Sometimes I understand something by writing about it. The effort to put whatever the idea or narrative is into coherent words forces coherent thinking. So here is a summary and commentary on Armstrong. I am hoping for a thoughtful helpful reply.

She begins by quoting a poem by Anna Barbauld: "Inscription for an Ice-House," and does a little close reading. She aligns it with a

closely similar poem (in time, type, mood), Keats’s "Ode to Autumn," showing the striking differences. She then asserts (rightly) that men do write differently, not simply as to subject and stance, but as belonging to debates in literature and the arts. the problem: we have not begun to work out a way to talk about female poetry which addresses the fundamental question of what they are means to us. I agree that when women’s poetry is contextualized with men’s we seem to get nowhere in understanding it nor even seeing its basic genres.

Armstrong’s argument is that the "gush of the feminine," the intense flow of emotion caught up in syntax and imagery, allows women to present and therefore analyse and think about their experience or what they know (know here in the deepest sense, what we can know and do know from the sheer existence granted us [by society]).

She then goes on analyzing Barbauld’s poem, contextualizing it in

Burke’s Sublime and Beautiful—in ways by the way that make

visible (to me) how sickening I find the fatuous complacency of

Burke’s male assumptions about what is beautiful (in women it seems is the beautiful found) and what it’s for (to exist passively for his delectation and this is supposed enjoyment for her). She finds Barbauld’s enactment of the beautiful puts her in the poem on the side of the powerless, vulnerable, controlled, except in the area of fertility which is beyond her and the male’s conscious control. Her capacity to reproduce becomes part of the food imagery (she makes the food) and makes her dependent, exploitable, and yet paralyzed (frozen or still in the imagery of the poem). She finds some parallels between "Inscription" and "Goblin Market" showing how the woman is seized up by her helplessness before her fertility and becomes both tomb and womb.

She then turns to Amelia Opie’s "Consumption" and Letita Landon’s "Calypso Watching the Ocean." In both we find women paralyzed before death and passively waiting, excluded from forms of power and movement. They are ill or they sob.

Now this sob, this intense held-back silent gasp half-alienated as

the woman attempts to silence or repress it is the gush of the

feminine that (in effect) Armstrong is saying is found in all women’s poetry as an essential quality. You might call it a glottal stop. It’s powerfully overdetermined by stories so the woman is not embarrassed to make it visible and strong in her poem. A sharp intake, a loss of breath, founded on inhibition and paralysis, a kind of spasm.

She then moves to Hume whose existential explanation of how we

experience life she calls useful for women particularly. This is not

the first place I’ve seen him used by someone wanting to elucidate women’s texts. Adela Pinch in Strange Fits of Passion begins with Hume before going on (quite brilliantly) to analyse Charlotte Smith’s poetry, Ann Radcliffe’s novels, and Austen’s Northanger Abbey. The idea is the way we understand existence is through sensed experience, perception apart from words or explanations.

She then turns to Felicia Heman’s "Arabella Stuart" (a wonderful poem by-the-bye—see just below) where we see the same qualities again, but this time tied to the heroine’s inability to work out whether what she remembers of the world outside her prison is a dream or happened. She moves on to Heman’s "Casabianca" and Amelia Opie’s "Mad Wanderer: A Ballad," the second of which I’ll copy and paste here:

Mad Wanderer: A Ballad

by Amelia Opie

There came to Grasmere’s pleasant vale

A stranger maid in tatters clad,

Whose eyes were wild, whose cheek was pale,

While oft she cried, "Poor Kate is mad!"

Four words were all she’d ever say,

Nor would she shelter in a cot;

And e’en in winter’s coldest day

She still would cry, "My brain is hot."

A look she had of better days;

And once, while o’er the hills she ranged,

We saw her on her tatters gaze,

And heard her say, "How Kate is changed!"

Whene’er she heard the death-bell sound,

Her face grew dreadful to behold;

She started, trembled, beat the ground,

And shuddering cried, "Poor Kate is cold!"

And when to church we brought the dead,

She came in ragged mourning drest;

The coffin-plate she trembling read,

Then laughing cried, "Poor Kate is blest!"

But when a wedding peal was rung,

With dark revengeful leer she smiled,

And, curses muttering on her tongue,

She loudly screamed, "Poor Kate is wild!"

To be in Grasmere church interred,

A corpse one day from far was brought;

Poor Kate the death-bell sounding heard,

And reached the aisle as quick as thought:

When on the coffin looking down,

She started, screamed, and back retired,

Then clasped it … breathing such a groan!

And with that dreadful groan expired.

Opie is responding to and creating poems in the then familiar Wordsworth mode about a devastated poor person who half-made wanders the countryside—except in Opie the female or vulnerable proud and nearly destroyed person is seen and felt from within, not seen as in Wordsworth outwardly as enigmatic with other themes criss-crossing (mostly judgemental) the narrative.

Opie’s Kate is paralyzed by her exclusion. She is outside law and custom (as have been several of the figures in the above poems) but were she inside the law her identity would have been just as surely controlled, annihilated, paralyzed.

Armstrong is saying the that what’s at stake in the gush of the

feminine in women’s laws is the discourse of law and power that

transgresses, enforces, excludes them. In her "Calypso Watching the Ocean," Landon cannot allow the least reference to her real state to emerge: she had had three children out of wedlock and had had to hide them and her own impoverished and exploited state as a literary editor’s abused mistress. If she tells, she will be despised, blamed yet worse.

Fierce laconicity is then the quality we come upon when we analyze, pay attention to the gush of the feminine by comparing women’s poems to one another where this quality of gush is over-the-top.

The essay is an argument for developing a way to read and to

understand women’s poetry apart from men’s, for only by doing that can we understand it.

I’d like to end by saying that over on the academic Romantics list which is titled NASSR-l, two often venomous men are trashing Hemans in order to ridicule the women and men on the list who enjoy her poetry and have spent years producing editions. One of these men is outside the academy and is ignored by people on the list: among other things he insists that Percy Bysshe Shelley was homosexual and wrote Frankenstein; the other (as he unashamedly presents himself on this list) is a malicious-tongued authoritarian man, who enjoys insulting others egregiously, all the while he’s driven to write long detailed learned emails to show off his knowledge of nowadays abstruse matters of prosody and classical learning; he’s the type to uphold a fascist society.

I still remember coming up an old book of Hemans’ poetry (maybe 20 years ago) in a used bookshop. It contained the whole of Hemans’ Records of Women. I had read about Arbella Stuart’s astonishingly unahamedly preyed-upon wretched life in an essay by Alice Meynell, and when I saw one of the records was about her, I hurried to read it. I was so moved, and I went on to read most of the Records of Women. It was the content that appealed: the stories, types of women, imagery, and the intensity of her tone. Since the new scholarly editions of her are so expensive, I had not until yesterday indulged myself in a new book—yesterday when I found a used copy of Gary Kelly’s Broadview edition of Hemans’s poetry for less than $14 (before postage).

I’ll end this letter to you by sending you this poem which once so entranced and held me. Hemans includes by way of preface a romantic retelling of Stuart’s story which emphasizes how Seymour deserted Arbella but I omit this here. You can read this preface at the Celebration of Women Writers.

For a review of an excellent book of essays about the letters of early modern women, I read through Arbella Stuart’s letters in Sara Jayne Steen’s edition. Hemans and Meynell’s emphasis on the egregious ruthlessness and injustice of the way Arbella was treated are accurate; where they censor themselves or change her story is that they don’t sufficiently blame Stuart’s guardians (aunts, grandmothers and grandfathers, uncles): it was the older people in charge of this young girl once she was made an orphan who treated her viciously and coldly. Alas, there’s no reason to think her parents would have behaved much differently. They might have tried to justify themselves to her (with just the sort of lies I’ve heard from my mother and been told other parents tell the children they seek either to own or intimidate), which none of her slightly farther-off relatives ever did.

Here’s her story on Wikipedia. What’s omitted here is there is good evidence that Stuart did not go mad in her last years, but was bullied into silence and left desolate and alone and any letters she wrote at the time destroyed. So we cannot refute whatever is said about her at the time: to call her mad is to get people to dismiss her. Nor can we ever break the void and understand what she experienced.

ARABELLA STUART.

by Felicia Hemans

And is not love in vain,

Torture enough without a living tomb?

BYRON.

Fermossi al fin il cor che balzò tanto.

PINDEMONTE.

I.

‘TWAS but a dream!–I saw the stag leap free,

Under the boughs where early birds were singing,

I stood, o’ershadowed by the greenwood tree,

And heard, it seemed, a sudden bugle ringing

Far thro’ a royal forest: then the fawn

Shot, like a gleam of light, from grassy lawn

To secret covert; and the smooth turf shook,

And lilies quiver’d by the glade’s lone brook,

And young leaves trembled, as, in fleet career,

A princely band, with horn, and hound, and spear,

Like a rich masque swept forth. I saw the dance

Of their white plumes, that bore a silvery glance

Into the deep wood’s heart; and all pass’d by

Save one–I met the smile of one clear eye,

Flashing out joy to mine. Yes, thou wert there,

Seymour! a soft wind blew the clustering hair

Back from thy gallant brow, as thou didst rein

Thy courser, turning from that gorgeous train,

And fling, methought, thy hunting-spear away,

And, lightly graceful in thy green array,

Bound to my side; and we, that met and parted,

Ever in dread of some dark watchful power,

Won back to childhood’s trust, and fearless-hearted,

Blent the glad fulness of our thoughts that hour,

Even like the mingling of sweet streams, beneath

Dim woven leaves, and midst the floating breath

Of hidden forest flowers.

II.

’Tis past!–I wake,

A captive, and alone, and far from thee,

My love and friend!–Yet fostering, for thy sake,

A quenchless hope of happiness to be,

And feeling still my woman’s spirit strong,

In the deep faith which lifts from earthly wrong

A heavenward glance. I know, I know our love

Shall yet call gentle angels from above,

By its undying fervour; and prevail,

Sending a breath, as of the spring’s first gale,

Thro’ hearts now cold; and, raising its bright face,

With a free gush of sunny tears, erase

The characters of anguish. In this trust,

I bear, I strive, I bow not to the dust,

That I may bring thee back no faded form,

No bosom chill’d and blighted by the storm,

But all my youth’s first treasures, when we meet,

Making past sorrow, by communion, sweet.

III.

And thou too art in bonds!–yet droop thou not,

Oh, my belov’d!–there is one hopeless lot,

But one, and that not ours. Beside the dead

There sits the grief that mantles up its head,

Loathing the laughter and proud pomp of light,

When darkness, from the vainly-doting sight,

Covers its beautiful! 1 If thou wert gone

To the grave’s bosom, with thy radiant brow,

If thy deep-thrilling voice, with that low tone

Of earnest tenderness, which now, ev’n now,

Seems floating thro’ my soul, were music taken

For ever from this world,–oh! thus forsaken,

Could I bear on?–thou liv’st, thou liv’st, thou’rt mine!

–With this glad thought I make my heart a shrine,

And, by the lamp which quenchless there shall burn,

Sit, a lone watcher for the day’s return.

IV.

And lo! the joy that cometh with the morning,

Brightly victorious o’er the hours of care!

I have not watch’d in vain, serenely scorning

The wild and busy whispers of despair!

Thou hast sent tidings, as of heaven.–I wait

The hour, the sign, for blessed flight to thee.

Oh! for the skylark’s wing that seeks its mate

As a star shoots!–but on the breezy sea

We shall meet soon.–To think of such an hour!

Will not my heart, o’erburdened by its bliss,

Faint and give way within me, as a flower

Borne down and perishing by noontide’s kiss?

–Yet shall I fear that lot?–the perfect rest,

The full deep joy of dying on thy breast,

After long-suffering won? So rich a close

Too seldom crowns with peace affection’s woes.

V.

Sunset!–I tell each moment–from the skies

The last red splendour floats along my wall,

Like a king’s banner!–Now it melts, it dies!

I see one star–I hear–’twas not the call,

Th’ expected voice; my quick heart throbb’d too soon.

I must keep vigil till yon rising moon

Shower down less golden light. Beneath her beam

Thro’ my lone lattice pour’d, I sit and dream

Of summer-lands afar, where holy love,

Under the vine or in the citron-grove,

May breathe from terror.

Now the night grows deep,

And silent as its clouds, and full of sleep.

I hear my veins beat.–Hark! a bell’s slow chime.

My heart strikes with it.–Yet again–’tis time!

A step!–a voice!–or but a rising breeze?

–Hark! haste!–I come, to meet thee on the seas.

- * * * * * * *

VI.

Now never more, oh! never, in the worth

Of its pure cause, let sorrowing love on earth

Trust fondly–never more!–the hope is crush’d

That lit my life, the voice within me hush’d

That spoke sweet oracles; and I return

To lay my youth, as in a burial-urn,

Where sunshine may not find it.–All is lost!

No tempest met our barks–no billow toss’d;

Yet were they sever’d, ev’n as we must be,

That so have lov’d, so striven our hearts to free

From their close-coiling fate! In vain–in vain!

The dark links meet, and clasp themselves again,

And press out life.–Upon the deck I stood,

And a white sail came gliding o’er the flood,

Like some proud bird of ocean; then mine eye

Strained out, one moment earlier to descry

The form it ached for, and the bark’s career

Seem’d slow to that fond yearning: it drew near,

Fraught with our foes!–What boots it to recall

The strife, the tears? Once more a prison-wall

Shuts the green hills and woodlands from my sight,

And joyous glance of waters to the light,

And thee, my Seymour, thee!

I will not sink!

Thou, thou hast rent the heavy chain that bound thee;

And this shall be my strength–the joy to think

That thou mayst wander with heaven’s breath around thee;

And all the laughing sky! This thought shall yet

Shine o’er my heart, a radiant amulet,

Guarding it from despair. Thy bonds are broken,

And unto me, I know, thy true love’s token

Shall one day be deliverance, tho’ the years

Lie dim between, o’erhung with mists of tears.

VII.

My friend! my friend! where art thou? Day by day,

Gliding, like some dark mournful stream, away,

My silent youth flows from me. Spring, the while,

Comes and rains beauty on the kindling boughs

Round hall and hamlet; Summer, with her smile,

Fills the green forest;–young hearts breathe their vows;

Brothers, long parted, meet; fair children rise

Round the glad board; Hope laughs from loving eyes;

–All this is in the world!–These joys lie sown,

The dew of every path. On one alone

Their freshness may not fall–the stricken deer,

Dying of thirst with all the waters near.

VIII.

Ye are from dingle and fresh glade, ye flowers!

By some kind hand to cheer my dungeon sent;

O’er you the oak shed down the summer showers,

And the lark’s nest was where your bright cups bent,

Quivering to breeze and rain-drop, like the sheen

Of twilight stars. On you Heaven’s eye hath been,

Thro’ the leaves pouring its dark sultry bIue

Into your glowing hearts; the bee to you

Hath murmur’d, and the rill.–My soul grows faint

With passionate yearning, as its quick dreams paint

Your haunts by dell and stream,–the green, the free,

The full of all sweet sound,–the shut from me!

IX.

There went a swift bird singing past my cell–

O Love and Freedom! ye are lovely things!

With you the peasant on the hills may dwell,

And by the streams; but I–the blood of kings,

A proud unmingling river, thro’ my veins

Flows in lone brightness,–and its gifts are chains!

–Kings!–I had silent visions of deep bliss,

Leaving their thrones far distant, and for this

I am cast under their triumphal car,

An insect to be crushed.–Oh! Heaven is far,

Earth pitiless!

Dost thou forget me, Seymour? I am prov’d

So long, so sternly! Seymour, my belov’d!

There are such tales of holy marvels done

By strong affection, of deliverance won

Thro’ its prevailing power! Are these things told

Till the young weep with rapture, and the old

Wonder, yet dare not doubt,–and thou, oh! thou,

Dost thou forget me in my hope’s decay?

Thou canst not!–thro’ the silent night, ev’n now,

I, that need prayer so much, awake and pray

Still first for thee.–Oh! gentle, gentle friend!

How shall I bear this anguish to the end?

Aid!–comes there yet no aid?–the voice of blood

Passes Heaven’s gate, ev’n ere the crimson flood

Sinks thro’ the greensward!–is there not a cry

From the wrung heart, of power, thro’ agony,

To pierce the clouds? Hear, Mercy! hear me! None

That bleed and weep beneath the smiling sun,

Have heavier cause!–yet hear!–my soul grows dark

Who hears the last shriek from the sinking bark,

On the mid seas, and with the storm alone,

And bearing to th’ abyss, unseen, unknown,

Its freight of human hearts?–th’ o’ermastering wave!

Who shall tell how it rush’d–and none to save?

Thou hast forsaken me! I feel, I know,

There would be rescue if this were not so.

Thou’rt at the chase, thou’rt at the festive board,

Thou’rt where the red wine free and high is pour’d,

Thou’rt where the dancers meet!–a magic glass

Is set within my soul, and proud shapes pass,

Flushing it o’er with pomp from bower and hall;

I see one shadow, stateliest there of all …

Thine! What dost thou amidst the bright and fair,

Whispering light words, and mocking my despair?

It is not welI of thee!–my love was more

Than fiery song may breathe, deep thought explore;

And there thou smilest while my heart is dying,

With all its blighted hopes around it lying;

Ev’n thou, on whom they hung their last green leaf

Yet smile, smile on! too bright art thou for grief.

Death!–what, is death a lock’d and treasur’d thing,

Guarded by swords of fire? 2 a hidden spring,

A fabled fruit, that I should thus endure,

As if the world within me held no cure?

Wherefore not spread free wings–Heaven, Heaven! control

These thoughts–they rush–I look into my soul

As down a gulf, and tremble at th’ array

Of fierce forms crowding it! Give strength to pray,

So shall their dark host pass.

The storm is still’d.

Father in Heaven! Thou, only thou, canst sound

The heart’s great deep, with floods of anguish fill’d,

For human line too fearfully profound.

Therefore, forgive, my Father! if Thy child,

Rock’d on its heaving darkness, hath grown wild,

And sinn’d in her despair! It well may be,

That Thou wouldst lead my spirit back to Thee–

By the crush’d hope too long on this world pour’d,

The stricken love which hath perchance ador’d

A mortal in Thy place! Now, let me strive

With Thy strong arm no more! Forgive, forgive!

Take me to peace!

And peace at last is nigh.

A sign is on my brow, a token sent

Th’ o’erwearied dust, from home: no breeze flits by,

But calls me with a strange sweet whisper, blent

Of many mysteries.

Hark! the warning tone

Deepens–its word is Death. Alone, alone,

And sad in youth, but chasten’d, I depart,

Bowing to heaven. Yet, yet my woman’s heart

Shall wake a spirit and a power to bless,

Ev’n in this hour’s o’ershadowing fearfulness,

Thee, its first lovetender still, and true!

Be it forgotten if mine anguish threw

Drops from its bitter fountain on thy name,

Tho’ but a moment.

Now, with fainting frame,

With soul just lingering on the flight begun,

To bind for thee its last dim thoughts in one,

I bless thee! Peace be on thy noble head,

Years of bright fame, when I am with the dead!

I bid this prayer survive me, and retain

Its might, again to bless thee, and again!

Thou hast been gather’d into my dark fate

Too much; too long, for my sake, desolate

Hath been thine exiled youth; but now take back,

From dying hands, thy freedom, and re-track

(After a few kind tears for her whose days

Went out in dreams of thee) the sunny ways

Of hope, and find thou happiness! Yet send,

Ev’n then, in silent hours, a thought, dear friend!

Down to my voiceless chamber; for thy love

Hath been to me all gifts of earth above,

Tho’ bought with burning tears! It is the sting

Of death to leave that vainly-precious thing

In this cold world! What were it, then, if thou,

With thy fond eyes, wert gazing on me now?

Too keen a pangand yet once more,

Farewell!–the passion of long years I pour

Into that word: thou hear’st not,–but the woe

And fervour of its tones may one day flow

To thy heart’s holy place; there let them dwell

We shall o’ersweep the grave to meet–Farewell!

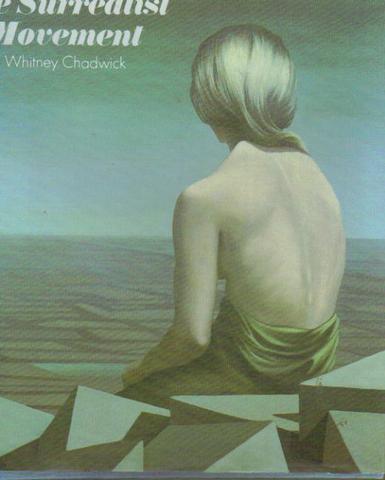

Understood more widely (generalization hopping), we can see that the laconic in female gothic is another expression of this "gush" of the feminine that Armstrong so brilliantly explicates. To picture this I send you the cover illustration for a recent volume of gothic stories by women: Two Centuries of Women’s Supernatural Stories, edited and introduced (the essay is right there, online) by Jessica Amanda Salmonson.

Kay Sage (1898-1963), Le Passage (1956)

There is the silence and void women are still forced into. She gazes into it and we do not see her face. She is blonde and thin enough for her bones to show. In earlier women’s poetry we have a fit, sudden gush, a spasm; in modern women’s poetry, paralyzed intensity. Violent female gothicism (e.g., Wharton’s) is fiercely laconic. This is the tone of Emily Bronte’s poems. So Isobel Armstrong has also explicated one of the characteristic tones and ploy-resorts of the plot-designs of women’s ghost stories.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From a friend on ECW:

Dear Ellen,

What an interesting post. I read your entry on the blog and was moved by it.

It does seem hopeful, especially with the publication of Armstrong’s work, that women’s poetry is beginning to be judged for its own merits rather than by the same standards as men’s poetry (as Armstrong states, men and women write differently). A pity about those two "gentlemen" on the list who lambaste Hemans' work. They remind me of an enlightened college boy who shared his father’s view of a woman’s period, and all she suffers as a consequence, existing solely in her head.

Society and the view of women is a tangled history. I remember reading about the myths changed from being matriarchal to patriarchal (look at how poor Medusa suffered)—a change that began, one could say, when men discovered that the miracle of birth happened not spontaneously, but with their help. It seemed women were no longer revered, and their subjugation began. Slowly, I think, the pendulum is slowly swinging the other way, but the two gentlemen on your list (as well as others), are resistant to this swing, and are doing their best to ignore or stop it.

Sigh…

Thank you again for your post. What a way to begin one’s morning!

Marjorie

Marjorie Gilbert

author of THE RETURN

a historical novel set in Georgian England

www.marjoriegilbert.net

— Elinor Jun 8, 10:26am # - When you speak of feeling alone, Ellen, I can see why you love this poetry so. Reading these are like hearing the cries, the sighs, the moans (of pleasure and of sadness) of other lonely women, through the ages.

— Tatyana Jun 8, 6:37pm # - I think matriarchal myths were replaced by patriarchal stories when men gained power over women, not when they realized they were part of the reproductive cycle (as if they hadn’t known). Men gained this power with the domestication of herds, which they could control, and the consequent advent of private property. Until then the role of women in providing food (from gardens) and sustaining the community (and its offspring) was at least equal to that of men (the hunters and gatherers dependent on chance) and probably greater.

But this response to Marjorie’s comment above is beside the main point Ellen has been making. I’ve been following the discussion about Hemans, and I think the whole argument can lead to some valuable insights about different kinds of aesthetic criteria—but this is not easy to do.

— bob Jun 8, 6:55pm # - A perverse comment by the vicious bully on NASSR-l: he puts on the list a comment that my not naming him is dishonest. No. It's discreet. But if he wants all who come to this blog and read the comments to know his name, fine.

I'm reading a book about bluestockings where the author, Sylvia Myers, asks why men persist in a cruel treatment of women who are learned. She says Gerda Lerner argues there's no mystery: it's a matter of power. So this cruel triumphant jeering man's name is Steven Willett and he teaches in Japan. I’ve read how cruel the school system is to Japanese students. I can see him driving people to suicide, contentedly, gleefully. He gets a kick out of scorning all sorts of people and his reactionary politics are also a function of his privileged position.

I've now unsubscribed. I should have earlier. On both NASSR-l and C18-l are male listowners who do not moderate. At the core of the refusal of men to moderate is not some principled idea about free exchange of ideas, for ideas are not what is exchanged. It's macho maleness. The men allowed to do this get their jollies this way. And the worst offenders are men. NASSR-l is worse since there are egregiously horrible men on the list who write postings whose utterances they would not dare in physical space, and which should not be permitted to go through.

Both lists do exemplify the sort of thing that drives women from lists that I discussed in my "Women in Cyberspace." http://www.jimandellen.org/ConferencePapers.WomenCyberspace.html

Since this is a blog and I can say what I wish I'll add this has depressed me. I still have NASSR-l on my GMU mail and don't know how to get rid of it, and see there are messages where three of these men (including the reactionary Jim Rovira). Willett is enjoying himself writing invectives, kicking someone in public mightily. I should have remembered one can never get back at evil since evil is obdurate and indifferent. That was Fielding's central insight in _Tom Jones_. Well I've gotten off that list now and will never get back on again. They'll tire of ridiculing and shaming my presence with my name after a while. The listowner is to blame here too. That's what happened on Austen-l; I have gone back there but only put on the briefest emails (once I did a little more and the obnoxious types immediately smelt blood; Miss Schuster-Slatt came to my rescue then).

Morning ruined (on top of that something went wrong with my email and then Edward wouldn't explain, but just did something technical and now it's just fine says he except I don't understand what was done in the least so it's not just find). It will take a while to forget,

Elinor

— Elinor Jun 9, 12:49am # - Dear Tatyana,

Armstrong attributes the spasms, fierce laconicity, sobs, gush, to being outside power and law and yet subject to it. Feeling helpless as well as all alone. LEL's life as we now know it exemplifies the state perfectly.

I find I often like the earlier women’s poetry equally or more than the more recent women's poetry; as I often like memoirs and letters (and a very few novels by 18th, 19th, & early 20th century women) better than many more recent novels (particularly the very contemporary which is not l'ecriture-femme). I can't say I like the earlier better necessarily, as they cannot and do not express so much that is central to life, but I often derive comfort from them where I do only in poetry, memoirs, and novels when the writer is very candid indeed and belong to the l'ecriture-femme mode (say Elizabeth Spencer's "Light in the Piazza").

It cannot be that I recognize myself literally in the earlier women's poetry or memoirs and letters, for I could not be more different. I do not appear in earlier literature except as someone despised (for class and exclusion based on sexual experience). I can’t identify as atheism (so central to my view of the world) is not there.

I don’t think it’s the loneliness though. Speaking generally, these early women who had the wherewithal to write (so were middle class) had little privacy. They were continually pushed into doing things and often forbidden education. Space was something they longed for as solitude was hard to come by until they were old and only then when they were not wanted. An exception would be Ann Radcliffe: and mocking derisory stories about her as mad appeared in print after she did retreat to Windsor. Other women who had solitude were stigmatized sexually (either had had sex outside marriage or were lesbian). Being simply broke or old was often not enough, e.g., Elizabeth Carter who was (I should add) made happy by her many friendships and visitings later in life.

Rather it’s the lack of demand that one be socially and financially successful.

I've often tried to think why I particularly am drawn to later 18th century women, French and English, and especially their memoirs. Nothing rivets me more than these diaries of women who are at court as marginal people. They are marginalized and yet there as individual women whose subjectivity counts, and they write out of it, at the same time as they enact feminine ideals I like; they tend to be strongly melancholy, acidly witty, and progressive in politics (enlightenment politics). Pre-20th century European culture as found in later English writers like Oliphant (a learned lady too) and Sand (lived freely and openly and yet alone and didn't care what other people think) are also very alluring to me. Perhaps one doesn't get this kind of thing in the 20th century since the women are still alive and as yet hiding in plain sight.

As you know, I find I am enormously cheered by writing; and when someone writes back who understands, fulfilled.

Elinor

— Elinor Jun 9, 12:58am # - Dear Bob,

You’re wrong about how women were treated in pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer cultures. These still exist and we can see how women are objects to be exchanged and are subjected to violence and utterly answerable with their bodies to the powerful men in the group who decide how the women will be used as things. They are beasts of burden; they have to kill the excess children.

From books I’ve read on tribes in the south pacific to modern novels about Africa today where tribal customs are still strong (Bessie Head), to anthropological and historical studies (of the aborigines by Robert Hughes for example), to talking to African women and Asian women students who tell me of what their mothers and older women endured (terrible beating is a matter of course, male promiscuity), nothing could be worse for women than tribal hunter-gatherer culture.

Some time read Things Fall Apart and Head's A Question of Power. Start to remember vaginal maiming and the cruelty and centrality of that. When male writers start to flatter themselves with the self-control of "chivalry," they're not wrong in the sense that there was a change in the later agricultural period in Europe which for the first time gave upper class chaste women a modicum of respect and valuing as individual people. And of course chivalry was mostly hypocrisy -- thought the ideal for treating women decently was at long last there.

I don't say many men didn't have it bad in hunter-gatherer groups, but the bad was like poor white men in the antebellum south and until the 1960s. At least they could despise those suffering worse than them; so too probably the average man who was not the alpha type in tribal culture.

Sylvia

— Elinor Jun 9, 7:59am # - Even if there are relics of hunter-gatherer societies today that are not egalitarian, the point I was making and should have made explicit is that material existence determines consciousness, not the other way around. The old goddess religions disappeared when men gained power, not when they became conscious of this or that. It’s silly to think otherwise.

— bob Jun 9, 3:11pm # - Bob,

Who with brains ever said otherwise? Have you read any of Braudel's masterpieces of history?

Not egalitarian seems an obfuscating word to use about the cruelty of institutions within a culture and powerful and not-so-powerful men to women.

And what does any of this have to do with women’s poetry? Women in such settings don't get to write poetry.

Sylvia

— Elinor Jun 9, 8:18pm # - I was responding to Marjorie’s idea about why one set of myths replaced another set. And my guess is that women in primitive societies did write poetry. After all, who created those early goddess religions?

I’m very sorry you felt it necessary to quit C18-L and NASSR. Your kind of contribution will not be made by anyone else on those lists. I know how irritated you get with people who are careless and less than respectful, but I wish you could keep on. I thought the sharp disagreement on Hemans might have led to real enlightenment, had you and others persisted. People need to learn to broaden their understanding of aesthetic success.

— bob Jun 9, 10:47pm # - Dear Bob,

I didn’t leave C18-l, only NASSR-l and am astonished you can think ridicule and the repellent talk by the spiteful pests of NASSR-l can produce any knowledge. Who can read malice?

Poetry is writing. I don’t know who created various religions, but they are anonymous ritualistic cultural uprisings. Utterly different.

Poetry is intellectual, a product of the educated imagination. Both men and women need to live above the animal level to begin to do it.

Sylvia

— Elinor Jun 9, 10:52pm # - Dear Ellen,

I think part of the spiritual communion you feel with eighteenth century women who were marginal figures at court, is because they are women who are in vulnerable positions (think adjunct professors) at the mercy of those who are their intellectual inferiors, and who retaliate for their perceived (else, why bother?) inferiority by exercising their power at every opportunity. This also reminds me of your experience on NASSR-L. Schoolyard bullies, when denied the outlet of physical brutality, resort to verbal taunting.

< br /> Jill

— Tatyana Jun 10, 7:49am # - Dear Jill,

You’re right. Actually it’s that the women are intellectually superior often, well-educated, with good taste, and thoughtful. When I came across Burney’s journals I fell in love with them; so too did I recognize aspects of myself in a remarkable memoir by a French women waiting to be guillotined—happily Mademoiselle des Echerolles survived -- and her memoir too. The latter was an important book for me; I came across it in my early 20s in a used bookstore (in English translation).

Our conversation tells me that the book I was talking about on ECW and WWTTA may be right for the English "bluestocking" set, but is not for the French. In England the "bluestocking" circles were mainly circles of friendship and support, an outgrowth of going to spas and spa culture. In France the saloniere element of fostering high independent thought, facilitating contacts between the thinkers, artist, and "movers" of the time was as or more important. It’s what the French saloniere was so admired for. But at the end of the day, when push came to shove these same women ended up desperate and living on minimal incomes someone else dispensed; the court ladies were women who had been minor people in these earlier salons.

All this connects to poetry too. Not just the women enabling one another to publish, encouraging one another, offering a context, but women who came into contact with them even tangentially were helped (Molly Leapor), and they stood as a visible model for aspiration. As I wrote on ECW and WWTTA, the cruelty hurled at them comes from their owning their own bodies and determining to make their minds, hearts, and imagination rule their lives.

On NASSR-l it's no coincidence that the poet ridiculed most often is Felicia Hemans, and the people doing the editions and most involved women. I came on and said I had loved Records of Women_ when I first came across it.

Elinor

— Elinor Jun 10, 11:03am #

commenting closed for this article