Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

More women's funny poems & "extreme female-adventure" & detective fiction · 4 July 06

My dear Harriet,

Elinor is tired tonight. Last week we had monsoon sheets of water pour down from the skies for three days and now on Sunday the sky broke out with lightning, fast-moving dark intense sudden squalls, and high fierce winds—so power outages occurred in many places—trees downed, roofs and walls smashed, lines cut and circuits broken. She and Edward and Yvette (and everyone in their neck of the woods in Alexandria) were without power for more than 17 hours. She did say she never thought before about how printed books are 19th century technology where all you need is a candle to red them. No electricity necessary. She stayed up late soothing her strained nerves reading.

So I thought I’d take over writing for a while. I want to tell you about the inspiriting book that got her through Sunday night: it discusses you and the book we appear in together (Gaudy Night): Maureen Corrigan’s Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading. We’ll return to what women enjoy reading and why:

Marilyn Monroe reading a 1950s style typically-packaged good book

But first more women’s funny poems.

Allthough she was not successful when she queried Victoria and Trollope-l for funny poems by 19th century women, on WWTTA Judy G wrote about new good anthology of poetry by 19th century American women, She Wields a Pen: American Women Poets of the 19th Century, edited by Janet Gray, where she found humor (a long comic poem in the book by Louisa May Alcott, ‘The Lay of a Golden Goose’, which includes jokes about transcendantalism), and in the poems of Phoebe Cary (1824-71), parodies of Shakespeare. Judy chose to type out three which she commented on:

I think the last, bitterly satiric, one of these is brilliant –

based on the famous "patience on a monument" speech from Twelfth Night. The first and last of these also tie in well with our

current discussion of Shakespeare’s sister [Judith, from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own:

Here is said first (on what a single life was like for gentlewomen before they were allowed education, and useful work for pay outside the family) and last:

Shakespearian Readings by Phoebe Cary

Oh but to fade, and live we know not where,

To be a cold obstruction and to groan!

This sensible, warm woman to become

A prudish clod; and the delighted spirit

To live and die alone, or to reside

With married sisters, and to have the care

Of half a dozen children, not your own;

And driven, for no one wants you,

Round about the pendant world; or worse than worse

Of those that disappointment and pure spite

Have driven to madness: ‘Tis too horrible!

The weariest and most troubled married life

That age, ache, penury or jealousy

Can lay on nature, is a paradise

To being an old maid.

My father had a daughter got a man,

As it might be, perhaps, were I good looking,

I should, your lordship.

And what’s her residence?

A hut, my lord, she never owned a house,

But let her husband, like a graceless scamp,

Spend all her little means, – she thought she ought,

And in a wretched chamber, on an alley,

She worked like masons on a monument,

Earning their bread. Was not this love indeed?

I went over to our shelves to John Hollander’s 2 volumes of 19th century poetry for the Library of America, and found the two Carys, Alice (1820-1871) and Phoebe. Phoebe did tend to comic parodies: in Hollander’s book there’s one of a Wordsworth Lucy poem, one of Goldsmith’s "When a Lovely Woman stoops to folly," one of Poe’s dirge on Helen in her kingdom by the sea (become Samuel Brown). I liked Alice’s even if not comic, and sent one meditating a landscape in a Turner painting:

Katrina on the Porch by Alice Cary

A Bit of Turner Put into Words

An old, old house by the side of the sea,

And never a picture poet would paint;

But I hold the woman above the saint,

And the light of the hearth is more to me

Than shimmer of air-built castle.

It fits as it grew to the landscape there

One hardly feels as he stands aloof

Where the sandstone ends, and the red slate roof

Juts over the window, low and square,

That looks on the wild sea-water.

From the top of die hill so green and high

There slopeth a level of golden moss,

That bars of scarlet and amber cross,

And rolling out to the further sky

Is the world of wild sea-water.

Some starved grape-vineyards round about

A zigzag road cut deep with ruts—

A little cluster of fishers’ huts,

And the black sand scalloping in and out

’Twixt th’ land and th’ wild sea-water.

Gray fragments of some border towers,

Flat, pellmell on a circling mound,

With a furrow deeply worn all round

By the feet of children through the flowers,

And all by the wild sea-water.

And there, from the silvery break o’ th’ day

Till the evening purple drops to the land,

She sits with her cheek like a rose in her hand,

And her sad and wistful eyes one way

The way of the wild sea-water.

And there, from night till the yellowing morn

Falls over the huts and th’ scallops of sand

A tangle of curls like a torch in her hand

She sits and maketh her moan so lorn,

With the moan of the wild sea-water.

Only a study for homely eyes,

And never a picture poet would paint;

But I hold the woman above the saint,

And the light of the humblest hearth I prize

O’er the luminous air-built castle.

Judy provided a little life of these now forgotten women of letters:

There’s an interesting short biography of Phoebe and her sister Alice: "Alice Cary and Phoebe Cary were born on a farm near Cincinnati, Ohio, fourth and sixth of nine children. They had little education and few books but began writing early in their lives. Alice started publishing poetry in periodicals in 1838 and was praised by Edgar Allan Poe and John Greenleaf Whittier. Both sisters achieved national recognition when Rufus Griswold included them in The Female Poets of America (1849). Both were abolitionists. Following publication of Poems of Alice and Phoebe Car’ (1850), the two sisters used their literary earning sto leave the farm and moved to New York City, where they set up housekeeping with Phoebe in the role of homemaker. Their Sunday evening receptions drew the New York literati. Alice became president of the American women’s club and filled a poetry column in the New York Ledger. Phoebe edited a book of hymns and worked briefly with Susan B Anthony’s suffrage paper, "The Revolution". Luxury editions of their last poems (1873) and the Poetical Works of Alice and Phoebe Cary with a ‘Memorial of Their Lives’ appeared posthumously."

Idyllic photo of 19th century woman reading

************

And now women reading women’s books, this time including detective fiction. What an inspiriting book for reading on a hot dark dawn morning by candlelight is Maureen Corrigan’s Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading. She writes of reading as intense adventure, as that which can interweave itself into the deepest fibres of our memories of things we do as we do them, what influences, directs, teaches, and comforts the reader who has that within her to be transformed. Corrigan’s tone is at moment luminous with remembered moments of strengthening and hope.

Yes, Harriet, it’s too Pollyanna (people returning from war are presented as all good feeling about their memories), and sometimes she will grate on your nerves by apologizing to those who wouldn’t read her book in the first place (a sort of bending over backwards to her readers who do worry about what the non-readers of the world would say). These are minor blemishes, though (they do not go on for very long) and are not the core of a book where reading has meant everything to the writer—and also about her career writing and teaching about her reading to an imagined community of readers and her students.

She vindicates, reads in front of her reader in the way of Bobbie Ann Mason in her The Girl Sleuth, "extreme female-adventure books" and detective stories. "Extreme female-adventure" books are classic women’s books and l’ecriture-femme by another name. Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Bronte’s Jane Eyre and Villette, Gaskell’s Mary Barton, and (for a modern example) Anna Quindlen’s One True Thing and Black and Blue make visible what the hard adventure of life is for women’ "terrible contests with solitude," "endurance" of the marriage market and successful socializing. fortitude, "keeping one’s nerves steady, the emotional power of confidence and a thoughtful strong mind, the long nightmare of being linked to a man for life who doesn’t "get you," who doesn’t begin to understand what means most to you (Kate Simon’s Bronx Primitive). Such books "got her through" her life, taught her much—just as Woolf said such books can.

By the time she gets to the end of her third long section and has told about adopting a Chinese baby girl, her time as a working class young woman at the prestigious and snobbish University of Pennsylvania, her career as a writer of reviews for the Village Voice and now on NPR, and her long-delayed marriage all the while validating and showing how reading and books have been important in each of her transitions, I felt I was communing with a non-philistine, decently humane presence validating the life of the mind.

The piece de resistance, Harriet, is a long wonderfully refreshing, fascinating and carefully qualified section on Sayers’s Gaudy Night in the context of what women’s communities can be for women, and in vindication of educated women. Corrigan worked at Byrn Mawr. She dwells on Harriet’s freely entered into relationship with Peter, how he is a knight who rescues her (from death, for she is accused of poisoning her lover-partner in Strong Poison). Then onto other women’s books of the 1920s and 30s, more detective fiction by women, memoirs (Lorna Sage’s Bad Blood).

The book’s title is somewhat misleading, for Corrigan also writes it to show the reader that detective fiction by men and women is not simply riveting or terrifying and sad entertainment (when it’s good as in Hound of the Baskervilles, or Hammet’s The Maltese Falcon, Chandler’s The Big Sleep or Susan Hill’s The Various Haunts of Men), but also an indirect means for discussing how it feels to lead a working life where the reader is liberated since the hero or heroine has autonomy, savvy, intelligence, wit. She sees detective fiction as an replacement for the Robinson Crusoe myth (work as seen also in Gaskell’s Mary Barton). The best of them invent communities of people who mirror real milieus of our world and are either therapeutic or worlds split open with all their banal harshnesses and horrors. She convinced me. But then it was 3 in the morning.

Throughout she brings up analogies with the same ones I so treasured when a girl: Nancy Drew, Little Women, nurse stories (for her it was Sue Barton) and autobiographies (by Agatha Christie including wry comments about how much is made of ten days Christie she fled wife- and motherhood). I wanted to tell her about Bobbie Ann Mason’s Clear Springs and Marge Piercy’s Sleeping with Cats.

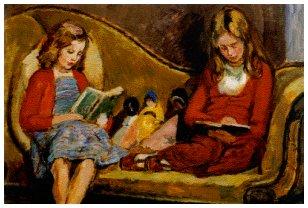

Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) Amaryllis and Henrietta [her granddaughters] (1952)

I’ve written before about how important girls books are to them: Girls’ books and women’s lives. The picture by Vanessa Bell (I love the rich reds and yellows) makes visible how good dolls are part of a young girl’s health-giving imaginative terrain. On WWTTA we noticed that although men will often use depictions of women reading to make "come hither fuck-me" pictures of these women for themselves (turning the women’s reading experience into forms of substitute masturbation), women often depict themselves reading in ways that call attention to their class status or inward emotional state, depict themselves as older women reading to children or paint young girls reading.

I’ve not gotten to the last part of Corrigan’s fiction: on what she learned from Catholic martyr stories (Mary Gordon’s Final Payments).

She does talk about the importance of parodies and funny books by women too: her candidate is Austen’s Northanger Abbey; this past Christmas on WWTTA we read Stella Gibbons’ often misrepresented Cold Comfort Farm (she made me want to read Barbara Pym’s _Quartet in Autumn), and her favorite poet seems to be Stevie Smith (!), but enough, it’s nearly 2. The air-conditioning is back, and I had better to bed.

A toute a l’heure, Harriet, stay dry and cool if you can, and get yourself Corrigan’s Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading.

Sylvia

PS. As commenting is closed, I’ll add this remark off-blog onto the letter as a Postscript. ON WWTTA I wrote:

"By-the-bye I read an article (well skimmed) about how mystery books are today transformed by women writers into feminist women’s novels of action."

Fran replied:

"I’ve always thought mystery stories in particular a rather good barometer or sometimes even harbinger of the changes in the perception of gender roles over the last hundred years or so and I’d class some of my own favourites in the genre as ‘feminist women’s novels of action’. What I have noticed, too, though lately is that quite a few of these formerly empowered and empowering serial female detective figures have suddenly become vulnerable victims of violence, rape and murder themselves, which doesn’t seem to augur well and may well reflect a conscious or unconscious sense of impotence in the face of so much present violence and conservative backlash…..."

To which I rejoined:

"Dear Fran and all,

The article was in Feminist Contributions to the Literary Canon: Setting Standards of Taste, ed. Susanne Fendler, and the article on "The Transformation of a Literary Genre—the Feminist Mystery Novel" by Marion Frank. Frank’s optimistic or positive attitude is partly the result of her central focus: Dorothy Sayers’ and particularly Gaudy Night; the other author she goes into at length (whom I’d never heard of before) is Joan Smith. Maureen Corrigan’s Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading is also basically an upbeat tale when it comes to what is found in the "extreme female-adventure" novel; she too focuses on Gaudy Night. She’s much soberer when she begins to talk about real life.

I wrote somewhere recently that I am often puzzled when people say they find such comfort in mystery novels. Perhaps that’s because when I’ve tried one I’ve tried more recent ones. So last summer I tried Susan Hill’s The Various Haunts of Men and felt frightened. It was about a serial killer-rapist who does murder the amateur detective-heroine; a man replaces her.

When you begin to study plot-designs you discover more of them use the detective paradigm at some point or wholly than you thought so it’s hard to make generalizations too."

S.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Addendum: RJ has written a moving blog about his encounter with another such book:

Ann Fessler’s The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades before Roe v. Wade.

http://www.portifex.com/DailyBlague/archives/2006/07/independence_da_2.html

Sylvia

— Sylvia Jul 4, 10:50am # - Dear Sylvia,

I, too, admired Corrigan’s book about reading. After finishing it, I was curious to read what other great readers had to say about reading: I discovered a marvelous collection of essays by Wendy Lesser, the title of which escapes me, and a collection of essays which originally appeared in The American Scholar, edited by Anne Fadiman. But Corrigan’s and Lesser’s books are more inspiring somehow. It’s nice to have a whole book in which you learn the tastes of one reader/writer.

— Kathy Jul 12, 9:12pm # - Dear Kathy,

As I wrote on WWTTA, it’s very good to hear from you. I’ve been having a busy summer—I’ve been reading women’s poetry for a review, started a third new project (Anne Murray, Lady Halkett) and am now going off to deliver my paper on Trollope's "Comfort Romances" at Exeter (Devonshire).

Still I’m often up late at night, unable to sleep and wanting to be cheered by being absorbed in a book. I just loved Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading – for its inspiration. I have Lesser’s Nothing Remains the Same (paperback). Is that the one you mean? If so, it’ll be one I take with me to read for the week.

I find Anne Fadiman very intelligent, but somehow (the ones I’ve read) too cool, too distant or polite and judicious. Maybe I’ve not read the right book by her, only the occasional essay. She does love books.

Corrigan loved Gaudy Night as well as Austen. Her favorites are woman’s books and often popular genres. Lesser’s as I peek in look more erudite, not at all women’s books primarily. I admit another reason for the deep pleasure I took in Corrigan's book is she loved the same books I did (well not the Catholic self-flagellating ones at the end), but many of her choices are my favorites too.

I hope you are not too hot and your summer has been passing pleasantly.

Sylvia

— Sylvia Jul 12, 11:19pm #

commenting closed for this article