Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Back to the 17th century (2), Trollope & women's autobiography · 9 August 06

Dear Marianne,

Remember how I wrote you a letter I called Back to the 17th century last April. I kept up this reading on and off between other projects until about a week before going to the Trollope conference when I returned to Trollope and the paper. Last week I finished my review of the book on women poets, & this Monday sent off a 1st finished copy to Jim M. What to do? I again immersed myself during the day in said 17th century, using the intertextuality of Anne Murray Halkett’s memoir to guide me in my choice of texts. In the later afternoon I work on my etext edition of her memoir. It’s coming out beautiful.

Herewith what I’ve been reading. Why? I can’t sleep more than 4-5 hours in a row usually, I’m too tired to read (oddly when my mind is tired while I can’t get it to process words I can write myself into half-wakefulness and write away), and I’ve no one to talk to. Nothing of interest on my lists left to respond to. I have no patience for TV. So …

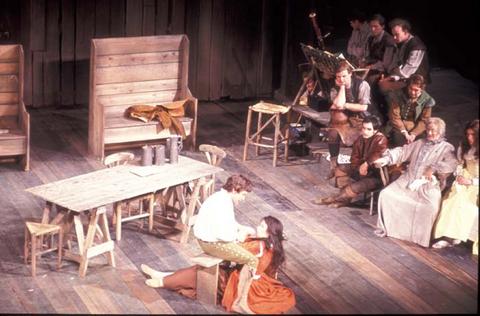

Fletcher’s _Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC revival 2003): A Celia type plays the lute

I began the week by reading Fletcher’s Humorous Lieutenant for 2 days. He and Beaumont (if both wrote the play) present play after play where at its center is an adult sophisticated interpretation sexual need, want, pleasure —as these things are understood by men it goes without saying of course. Anne Murray identified with the marginalized heroine, Celia, who is almost raped and therefore almost an outcast. Here are the lines she recalled explicitly. Celia was humiliated and snubbed until the prince deigned to lean over and kiss her; then all the courtiers couldn’t abase themselves before her enough:

Celia

My servants, and my state:

Lord, how they flocke now? ...

Before I was affraid they would have beat me;

How these flies play i’th Sunshine? pray ye no services,

Or if ye needs must play the hobby horses,

Seek out some beautie that affects ‘em: farewell,

Nay pray ye spare: Gentlemen I am old enough

To go alone at these yeares, without crutches.

The same rough-spoken bitten-off ironic anger is found everywhere in Hortenze Mazarin’s memoir. I now long to read Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed, a reversal of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (which Edward and I saw done marvelously by the Royal Shakespeare Company at Kennedy several years ago now). My excuse: Anne would have identified with those women too. And she has clearly read other plays of the same type—as well as novels, the former on the English stage and as read in bound books, the latter by French women and probably in the original French. A Wife for a Month also interests me: the treatment of women there would have made visible to her the sexual grounds of her existence, which grounds threatened Anne into behaving the way she did.

Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC 2003 revival): here the man is taming the woman.

So then I turned to insightful books and articles on autobiography, the drama, and marriage in the period. I’ll single out Paula Backscheider’s "Endless Aversion Rooted in the Soul," a study of how marriage is presented in the later 17th century drama; Josephine Donovan’s "Towards a Women’s Poetics," about the psychology of depressin and colonization, a schizophrenic or self-alienated point of view on the self, living in a private sphere which is non-progressive, repetitive and static, shared experiences and the centrality given over to child-rearing (pregnancies, menstruation), the dominant importance of the mother; Verna Foster’s "Sex Averted or Converted" in Fletcher’s plays (just brilliant); and Robert Hume’s "Marital Discord in English Comedy from Dryden to Fielding," the last sound, hard-hitting ("a woman had almost no legal recourse against a husband who proved vicious, tyrannical, or unfaithful"), with lots of clear analyses of lesser known good 18th century plays. Hume made me want to read Henry Fielding’s Modern Husband: like the men in the women’s novels and memoirs (Montbrillant, The Sylph, Edgeworth’s Leonora), this hero urges his wife to barter her body to his creditors to pay off his debts.

Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC 2003 revival): making the power structure comically visible?

As to books, Sheila Ottway and Sidonie Smith’s on autobiography when by women: how it looks, what forms it takes, how and why it’s dismissed and denigrated. Helpful descriptions of the shared characteristics of women’s memoirs. Women are not writing as a eminent public person who presents himself as playing an important in the spirit of the time. Women want to represent themselves; they’re recovering and recreating themselves. Meme: I will write a separate letter on this topic soon.

Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC 2003 revival): the women dancing

By Wednesay I was ready for I read Hortense and Marie Mancini’s memoirs. Someone at Montreal suggested to me the Mancini women memoirs appearing in print (and one in English) encouraged Anne Murray to write, and what is presented there influenced Anne. Certainly they are strikingly frank about private life. Marie depicts a mother-daughter relationship where Marie’s mother is deeply resentful of her daughter and dislikes Marie for what is perceived as ugliness, for Marie’s refusal to pretend to agree with all that is said around her and Marie’s overt disdain for the hypocrisy played upon her. The mother threatens her with punishment for her candour, saying (in effect) how dare you? Anne gives a frank portrait of her mother’s hostility to her too. It is a repeated motif in these 17th century memoirs by women: the mother who dislikes her daughter for being clever, a reader, and determined to find some genuine individual fulfillment in life.

Marie’s younger sister, Hortense Mazarin’s memoir is a drivingly intense justification for her having left a crazed possessive cruel husband. Like Anne’s, Hortense is seeing her life against the scrim of a need to apologize and find security because of the betrayal of the man she meant to turn to for protection.

Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC 2003 Revival): the dark house.

I should say the edition I’m reading the two memoirs in is revolting. The editor, Gerard Droscot, regards the women as sex-mad, and in his insinuating salacious notes suggests they would go to bed with just about anything that came into the room. He doesn’t go so far as to say they are inferior texts and must have been written by a man. On this see Elisabetta Graziosi’s "Lettere da un matrimonio fallito".

I can’t seem to get into Janet Todd’s The Secret Life of Aphra Behn. The book is good (how many long good books that woman has written!). It’s just too late in the night by the time I start.

I am though half-way through Frances Sheridan’s mid-18th century Sidney Biddulph: Sheridan does seem to me to indict women as to blame for whatever happens to Sidney and thus her book can make Burney’s far more disinterested and sympathetically woman-centered Cecilia look good in comparison. Burney too has a wider view of society and brings in its economic structure.

I did run errands, and go places by car. So I also listened to the very great Last Chronicle of Barset read aloud by David Case when in said car. (Thus far I’m the only one who’s posted about this book on Trollope-l and it may be we won’t have more than 4 people reading the book.)

As I restarted the book, I had just come across a story in the newspapers about Las Vegas. In Las Vegas the lawmakers passed a law making it illegal for any to "feed poor people" in the parks. How are we to tell who is poor? The language is set up to make a division, but then what police person is endlessly watching. This is a symbolic law meant to despise and scorn the poor, move them on. It comes just out of the same attitude as we open The Last Chronicle with.

Mr Crawley has a wretched underpaid existence. Does a soul feel

anything for him? Is there one person who proposes to up his

salary? No. They despise and scorn him, and especially for being in debt. He is driven nearly wild with trouble and anxiety and misery over the humiliation and his mind slips. Everyone is only too glad to blame him and say he must’ve stolen the money. Years of the man’s character means nothing. I have to admit I’m glad not to have been told he’s a lesson in "bad behavior." Perhaps he should never have been born, and certainly never married. A life alone rather than any comfort. Then the neighborhood would deem him strange.

The hardness and bleakness of this book, the attitudes towards money and success make it anew a book for our times, more true to ordinary experience than the books by Trollope recently in favor (The Way We Live Now, He Knew He Was Right). And very much in the Victorian tradition of Dickens and Eliot. No jokes about or at those who live in Hogglestock. Trollope is not amused nor does he indulge in caricature or the ever popular comic grotesques of Victorian fiction. He doesn’t laugh at those who suffer from ostracism or intense self-consciousness. After all it is snobbish and cruel (I stopped reading Dickens when I came across it one last time [the straw that broke the camel’s back] in Chuzzlewit. Instead of compassion, Dickens meted out ridicule.)

Trollope is (as ever) my exception—for Sidney continues, develops, refines, makes poignant and crazed the same concerns of 17th century women’s autobiographies, including the epistolary style.

Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC revival): 20th century play refines and makes poignant male-female relationships

A kind person on C18-l asked me to join in on a multi-person blog about the long 18th century, but I couldn’t seem to log in on Bloggers and then I don’t understand how it can be a multi-person blog unless I can type directly on the same one others do. Perhaps it will come clear eventually.

I like to send a poem and picture. So here’s a brief poem by James Graham, 5th Earl & 1st Marquis of Montrose (1612-1650):

On himself, upon hearing what was his sentence

Let them bestow on every airth a limb

Open all my veins, that I may swim

To thee, my Saviour, in that crimson lake;

Scatter my ashes, throw them in the air:

Lord, since thou know’st where all these atoms are,

I’m hopeful once thou’lt re-collect my dust,

And confident thou’lt raise me with the dust.

Montrose’s sentence was to be hung, disembowelled, his intestines burnt, castrated and dismembered as a traitor, and all his parts distributed through the streets. To be sure, he himself had supported others who did the same to other people. Among other things I came across I discovered that despite an attempt to reform the marriage customs in the 1650s (a set of regulations was made which made it just like a modern marriage: you went to a JP and had a civil ceremony, itself preceded by sensible efforts to make sure there was no previous impediment, i.e., contracted marriage) women were still burnt at the stake for murdering their husbands no matter what his behavior had been.

Graham has other poems and is seen as a romantic figure by Walter Scott and others. Montrose was a Scots Royalist. Those who became prominent are often nowadays presented in vilifying terms—except when they are aristocratic-romantic. This would exclude Anne Murray’s probable bigamous husband, Joseph Bampfield, Presbyterian, sober, prosaic and under no illusions.

Fletcher’s Tamer Tamed (1611, RSC 2003 revival): the lovers (an modern image of Anne Murray & Joseph Bampfield?)

And the woman who dared to write her life with a wonderful bravura of bitter ironies just before Anne Murray Halkett sat down to write hers:

Hortense Mazarin (1649-1699).

I hope I’ve not wearied you with my life in books this week. The only one of my 3 Yahoo lists where there’s been talk has been WomenWriters and we’ve been talking more about Dorothy Sayers and Q. D. Leavis than Virginia Woolf. On Wompo there was a long extended thread about Anne Stevenson’s harshly critical view of Sylvia Plath’s vatic anger and lack of sympathy or understanding for her as a suicide. I wanted to talk of the connection between melancholy and poetry and how women behave as competitors and rivals. Both threads would provide long blogs in themselves. I have contributed to 19thCenturyLit’s discussion of Oliphant’s fascinating Hester. The people over there are engaged by the book (though already there’s been a posting admiring precisely the shallow stereotypical or caricature of a heroine Oliphant means us to scorn, to which however there have now been objections). On WWTTA we spent 3 months reading different novels and essays by Oliphant plus her autobiography.

And from all this I came up with the epigraph for my paper on Anne Murray Halkett. It’ll be from Woolf’s Orlando:

"Often the paper was scorched a deep brown in the middle of the most important sentence. Just when we thought to elucidate a secret that has puzzled historians for a hundred years, there was a hole in the manuscript big enough to put your finger through" (Chaper 3).

Thank you for listening, my dear. Any comments you’d like to make?

Elinor

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Speaking of Shakespeare, is 12th Night the play in which a woman dresses up as a man and falls in love with a man, and then a woman falls in love with her? I saw a videotape of one scene from that play in my theater class in 8th grade, so I don’t know anything about the play besides what I just said. The reason I am asking about that play is that my family decided to rent a movie for this evening, but we haven’t watched it yet because we are going to eat dinner first. The description of the movie is that a girl disguises herself as her twin brother, joins the boys soccer team, and helps them win the big game. She falls for a guy on the team. Is the character in 12th Night or whichever play it was named Viola? The character in this movie’s name is Viola, and that name sounds familiar. The cover of the movie says, "Duke wants Olivia who likes Sebastian who is really Viola whose brother is dating (can’t read the name because it’s blocked by the picture) so she hates Olivia" and the words continue, but they fade out, so you aren’t supposed to read it but it implies that it goes on and on. It sounds like a funny movie. It could be a problem that they are turning a Shakespeare play into a high school story, but maybe it’s not a problem. It makes me want to read the play, or maybe I can find a movie of it, because then I will know what the real story is.

— Jennica Aug 10, 9:04pm # - Dear Jennica,

It does indeed sound like Twelfth Night. The characters’ names clinches it.

However, Shakespeare wrote other plays with "breeches" roles. This word refers to a part where originally a boy played a girl playing a boy. This is more than a little piquant and suggestively repeatedly transgressive. People have suggested there was a homoerotic current in the boys playing girls playing boys parts in Shakespeare and other playwrights of his era. When actresses were specifically permitted in a statement about the new theatres of 1660, one "rationale" referred to boys on stage dressed as girls as sexually wrong and dangerous! (so there may have been a homosexual content here).

Boys playing girls playing boys: In Shakespeare these include As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Cymbeline (the heroine disguises herself as a boy).

Nowadays (and uniformly since 1660 in the English speaking theatre), a woman plays the role so it’s a woman dressed up as a woman playing a man. After actresses became common and then required (for female roles) on stage, these parts were sexually titillating for the heterosexual men in the audience to watch.

Many other playwrights besides Shakespeare wrote "breeches" roles for women, among them in the Jacobean period besides Shakespeare, Beaumont ahd Fletcher, and in the Restoration, Dryden. Mozart's _Marriage of Figaro_ has a male singer (counter-tenor) dressed as a boy who puts girls' clothes on.

E.D.

— Elinor Aug 10, 11:29pm # - From Kathy C.:

"Dear Ellen,

I was sorry to read about your insomnia. Not that that was the main point , but I know how awful that can be. I do admire your blog. It’s the perfect blend of academic analysis and personal (yet not too personal) revelation. I scrapped mine because I didn’t like my rough draft-y style.

I looked up the references to John Caldigate in your book while I was reading John Caldigate this week. I love Mr. Trollope’s books and found this a page-turner, but I had never heard of it. Bigamy and blackmail: material for a potboiler, but almost realistic in Trollope’s hands.

How do you rate it?

Kathy"

— Elinor Aug 12, 8:08am # - To which I replied:

Dear Kathy,

John Caldigate is a powerful book. Part of its power comes from its setting in Australia. You should now read "Catherine Carmichael; or Three Years Running" (about a woman forced to marry a man, a la The Piano)

I rate JC very high.

We read it on Trollope-l and you can find all sorts of postings on it here:

http://www.jimandellen.org/trollope/caldigate.show.html

and on "Catherine Carmichael" here:

http://www.jimandellen.org/trollope/catherinecarmichael.html

Caldigate one of of Trollope’s rare studs, and he ends up in jail and once he’s put in we just about never see him again. I’ve a posting on this. I didn’t bring him up in my "Masculinity" paper but he’s the exception that makes the rule (he’s punished for his studness and conventional success).

Did you look at my paper (AT’s Comfort Romances for Men) as now on line? It’s not too long and how beautiful Landow made it:

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/trollope/moody2/40.html

I’ve yet to link it into my website. Some time today :)

E.D.

— Elinor Aug 12, 8:09am #

commenting closed for this article