Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Anne Halkett's Memoir: separating out the bricolage · 16 August 06

Dearest Marianne,

Ah, the magic of sleep. I sometimes go to bed and think to myself, how is it I fall asleep? I would worry I will not except for a number of years now from experience I know if I tire myself enough and simply wait there, just half-relaxed, my mind does dissolve away.

Blest, blest oblivion, sleep. As, sleep it is a blessed thing … (as the poet says). It will come when I have tired myself sufficiently. So herewith another literary letter:

It’s fascinating how trying to follow a trail of thought & feeling leads to unexpected finds and into disparate eras.

As you know, I’m now taken up with Anne Halkett. I’m going to give one paper on her memoir at the coming EC/ASECS in Gettysburg this fall: "Anne Halkett’s War Memoir;" and another at the coming ACECS in Atlanta this spring: "A hole in the manuscript big enough to put your finger through: the Misframing of Anne Halkett’s Memoir."

In the case of the first panel, while I’m bound to talk about the advantages of belonging to a world where you circulated your writing in manuscript (you can be freer as it’ll reach very few), I’m going to concentrate on Anne’s war. The outer one is the easy part as it consists of a number of striking adventures, one famous: it was she who dressed James II up as a girl and enabled him to escape the Parliamentarians to Holland; she rescued a famous Scottish Royalist’s books (not a small thing when you consider books must be wrapped up and packed & the Cromwellian soldiers were at the door) and helped him and his wife on their way into the Scottish moors (the whole sequence reminded me of Anne Elliot in Persuasion packing up Kellynch and then at Upper Cross while the others scurry away); as in Gone with the Wind, she stood before a door with a pregnant woman next to her and told the soldiers who wanted to make sexual as well as other trouble to Fuck Off (in 17th century respectable language); she nursed soldiers coming back from the defeat at Dunbar; she argued with Cromwellians; she was threatened with sexual harassment more than once.

This last leads me to the harder part: her story is a struggle for personal security since she is in danger of falling out of loop of security as she is no longer regarded as an "honest" or "chaste" woman and thus fair game. Why? She married a man who was already married and on and off continued to live with him. One of the panels at the Atlanta ASECS is called ": "Well-behaved women seldom make history." Anne was not well-behaved. Told to her face that the man she had married was married to another first, she refused to appear to believe it. He stood alongside her and stoutly said he didn’t believe his wife was alive either. But they both knew she was.

The problem for me is to try to get some insight into why she is riven with such guilt, shame and remorse. It goes beyond fornication. After all she was not married to another; Bampfield was. What was her attitude towards her relationship with this man? He seems at first genuinely to have believed his wife was dead. She seems to have regarded herself as somehow betraying his wife too. What were the marriage laws and customs at the time, and how did the revolution and changes in mores (and laws too) affect what she did and how others saw it? What was her attitude towards the man who she finally did marry—- a genuine widower who pursued and pressured and finally married and protected her. She seems to have taught herself to appreciate and then loved him for his trust in her and kindness.

Well I’ve been reading a remarkable novel from the Gaslight period: Henrietta Palmer Stannard’s A Blameless Woman (later 1890s). The novel is iconoclastic because Stannard treats very sympathetically a heroine who when told she has however innocently or ignorantly married a man married to another decides to stay with him. Bigamy is a common theme and device in the Victorian novel: it allows for treatment of sexual anxieties, of conflicting attitudes towards marriage and what it’s supposed to be (signify), but usually the woman is the bigamist; whether a man or woman the bigamist is an aggressive ruthless manipulator; the atmosphere is lurid (sensational). In Stannard’s book the man and woman are not caricatures of conscious wrong-doers; they exhibit the confusion and contradictory motivations of everyday life. The heroine wants to return to her bigamous lover; she is pursued by another man who loves her and offers honorable marriage. I’m struck by how some of the half-lies and behaviors I see in Anne’s memoir recur in this novel.

I’m often so impressed with the texts from the era around 1880 to just before WW, especially in the plain style and quiet, bleak, or grimly real novels of Hardy, Gissing, Bennet, and the gothic and ghost stories by so many (Stoker, RLS, Oliphant to name but 3). Recently I read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s That Lass O’Lowrie, and Stannard’s book reminds me of Burnett’s.

Mary Augusta Ward (1851-1920) (as I don’t have a picture of Stannard I supply another Edwardian author)

Nonetheless, Anne’s memoir is better than A Blameless Woman because it’s real and naturally has thick-description, is naturally subtly and limitlessly ambiguous and real. She reveals so much more in her candid way. She would like us to see her as blameless but like the heroine of Stannard’s novel she actively chose her first man and stayed with him against advice and even violence (her brother-in-law duelled with Bampfield in an attempt to murder him).

Anne likens herself to Celia in The Humorous Lieutenant (as I wrote) so now I’ve gone on to other highly sexualized plays by Fletcher, e.g., A Wife for a Month. A Wife for a Month is about how the king wants his courtier to allow him to go to bed with his sister, in return for which the king will promote all sorts of men in the family and shower them with gifts. The sister refuses. The king holds out and then offers to divorce his wife. The analogies with Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon are meant (and echoe Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale and Henry VIII). But equally they echo a situation found repeatedly in women’s novels: the husband pressures the wife to go to bed with a friend/enemy to pay his gambling debts. Epinay’s Montbrillant, Spencer’s Sylph, Edgeworth’s Leonora are just a few with this motif. Recall how Burney was expected to get her family promoted , and how she hated what she saw happening at court. She didn’t tell all.

I’ve also been reading Scottish history in the 17th century (and looking at Scott’s novels once again), on the uses of autobiography as well as women’s. The notorious mid-19th century Yelverton case where a woman was in a similar position to Anne’s (married to a man married to someone else) and actually got to testify and wrote defenses of herself.

In the case of the second paper for the second panel, I’ll concentrate more on how these conflicts play out in the responses of her readers—who are similarly conflicted and (like many readers of Victorian novels) want to have an innocent heroine and villainous hero or vice versa or don’t want to think there has been a conscious bigamy as this undermines a rooted desire to find security in the ceremony of marriage. In what’s left of the manuscript Anne never openly says she and Bampfield married, so the act can be denied. They are having sex clandestinely and there were no children. I say what’s left because someone destroyed the original paratexts of the manuscript: the opener is destroyed; so too is the closer (which for all we know could comprise a long section about her married life to Halkett), and two key spots in the manuscript destroyed as well: how and where she met Bampfield and what she felt when she finally openly admitted she knew she was preparing to marry or had married a man married to someone else. My line of argument would lead me to discuss the later scholarship and how it misframed the memoir. The panel is called "paratexts."

Here Margaret Ezell’s book, Social Authorship and the Advent of Print comes in. Ezell’s book is an equivalent eye-opener to William St. Clair’s book on the real world of publishing and readers in the 19th century. We discover the most common books to get published were religious and practical (medical, cooking, self-help), and much circulation of texts was still through manuscript. She presents some of the advantages of not having your text be a commodity someone else is seeking to make a profit or prestige from.

It is utterly typical for a woman’s memoir to be published after her death, to be partly or centrally censored, and to be reframed by the next generation to hide anything subversive or threatening. I’m going to talk about what’s not there (very fashionable this) and what was substituted for the destroyed paratexts later. Really it’ll probably be about the later scholarship (often a form of conventionalized romancing) and then I’ll provide a new framing, one which brings out what is only implicit in the sad remnants of this woman’s difficult life: here is no romance, heroism, or certainty. In her last 20 odd years after the death of 3 of her 4 children by Halkett, she too was widowed (like both husbands before her—for Bampfield’s wife died a few months after Anne married Halkett), and she eked out a living far from her original place as a teacher in Scotland.

A question arises here also to which I’ve no answer: who is Anne writing to? Who is her audience. All her children were dead by that time; she lived apart from Halkett’s family and her own English relatives and friends were far away. I surmize from the stance she takes she imagines herself writing a defense of herself, an apology, and self-definition (of what she is) to a vaguely-sensed public. We might call that public posterity since she never appears to have made any attempt to publish her memoir. In her meditations you see how puzzling over events. How did it happen a small band of people took over the English state and killed the king when it seems so many were against this? And such like questions. Her answer is God caused this, but she’s not satisfied with that really.

From the 16th through early 17th century in Europe we have what survives of a sudden great flowering of magnficent poetry by women (Renaissance type, Louise Labe, Margaret d’Angouleme, Vittoria Colonna, Veronica Gambara, Gaspara Stampa, Mary Sidney Wroth and Mary Sidney Herbert) while from the 17th century saw a remarkable series of autobiographical writings. The poems were (many of them at any rate) published at the time (some women were overlooked); the autobioographies were mostly not and of those that were most are censored, though not as cruelly mutilated as Anne Halkett’s (with an real attempt at literal accuracy and telling what their lives were like, and this includes French women, i.e., Marie and Hortense Mancini, Marguerite de Valois, Marie-Madeleine de Lafayette’s letters and memoir of Henrietta d’Angleterre). You see, Marianne, she had the courage to talk even indirectly about her sexual and marital experiences and need for other women’s and powerful men’s support.

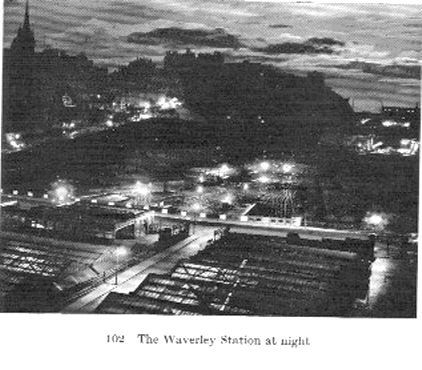

I end on a dark picture of Edinburgh from the 1940s. I began my etext edition with the earliest print of Edinburgh available to me; I’ll end it on this one. So much is left in the dark. Those into whose hands this manuscript fell were determined to destroy its breaking of taboos. Its brilliance and poignancy stopped whoever it was from killing Anne Murray Bampfield Halkett, removing her from history, altogether

Elinor

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- PS. On Stannard:

Henrietta Palmer Stannard wrote under more than one pseudonym (e.g., John Strange Winter) and produced many books. Some very dreadful were very popular (about cloying babies and military people—she married a military man). But she had a respectable career in journalism, worked for women’s journalists’ causes, and wrote a number of better adult novels. She was interested in the device or theme of bigamy in her novels as these function as sensational story devices which permitted her to explore issues in sex and marriage she couldn’t any other way.

A Blameless Woman makes me want to try Burnett's Shuttle (as far as I know about a divorce or separation and a brutal husband -- Burnett divorced 2 husbands herself).

E.D.

— Elinor Aug 17, 12:44am #

commenting closed for this article