Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Life as contingent arrangements in a marketplace: recent fiction & film · 24 September 06

Dear Harriet,

Ever since I read Maureen Corrigan’s (to me) cheering and intriguing book about the pleasure of reading women’s books, Leave Me Alone, I’m Reading, I’ve been half-thinking about her explanation for the popularity of mystery & detective & spy fiction. Corrigan suggests the story matter of these books, characters, plot-design, visibilia is a not-so-subtle substitute for the contemporary experience of life which comes from spending at least 8 hours a day working for a living. The anonymity, shallowness of relationships, irrationality and uselessness of a good deal of what is done to make a profit, the sudden networking, and just as sudden downfalls—are all paradigms of what most people spend most of their hours doing, and what they don’t want to admit to or discuss but are allured by when presented in the glamorous form of a spy job or mystery to solve.

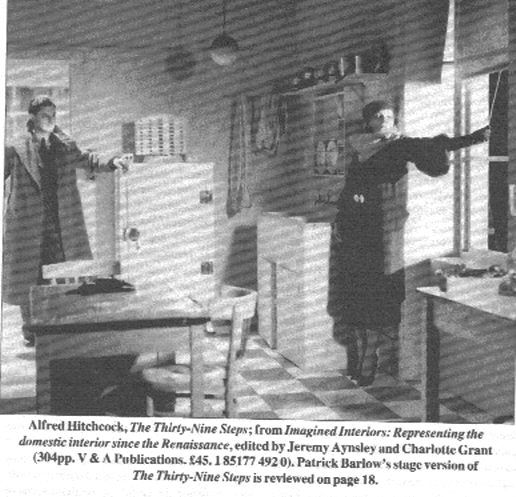

They are kitchen soap operas transformed. We can see this in the Hitchcock still from his 1935 film of the deeply reactionary spy thriller by John Buchan, Thirty Nine Steps. The actor is John Garfield, the actress forgotten (biodegradable?). They are in a kitchen just like those imagined typical in the 1950s on TV (Honeymooners):

I’ve been listening to David Case read aloud John LeCarre’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and this fiction as well as the superior Constant Gardener fits Corrigan’s thesis to a T. Constant Gardener is to my mind the finer book as instead of amoral thugs in a circle at the center, we have the sensitive fine non-violent hero, Justin Quayle. In TTSS, George Smiley enacts a wounded Mr Harding (from Trollope) refuging himself strangely in this other planet universe. Case uses the voice for Smiley he uses for Mr Harding.

Then this weekend I came across two articles in London Review of Books where I probably would not have taken note of the commentary buried deep in the article had I not read Corrigan. The first was short and appeared in TLS. Christina Hardyment reviewed 2 books on the writer Edith Hilda Young. Now Young’s novels are Virago type whose deepest paradigm is the struggle of the heroine against inward miseries inflicted on her as she experiences them at home by characters who are higher ranking and stultifyingly conservatives.

A small digression: After I closed The Second Common Reader (we are soon to begin Woolf’s Years on WWTTA), I began to wonder to myself about Woolf’s easy identifcation of Hardy as the great novelist of his generation with Gissing and Meredith coming in for 2nd place. I asked myself Do I believe he’s so great. Well, no. I don’t. Are any of them better say than Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Shuttle—which none of the three could or would have written? Henrietta Palmer Stannard’s A Blameless Woman (a candid and poignant account of a young woman who without knowing it marries a man already married to someone else and stays with him) is beyond Hardy’s distrust of women and frequent dislike of them.

In Hardyment’s article on E. H. Young, Hardyment says that Woolf kept her distance from Young (wrote about Young with "slightly grudging respect") though Young much admired Woolf’s work. In the article the reviewers say how Young was influenced by Austen. No. Young’s books are written all over by the spirit of Woolf. They come out of ideas about luminous particulars making up reality and are closer to later 19th century fiction than anything Austen wrote. Woolf’s sense that after all women’s fictions were not accepted made her not think to read them in the spirit of finding what was finest in the era in such books. (Woolf scorns Oliphant for selling her brains in A Room of One’s Own.) Where in the last part of The Second Common Reader devoted to late 19th century fiction are any women authors? Burnett, Ward, Oliphant, Stannard? To me Hardy cannot be the supreme author of the era for his casual misogyny and also the hostility to Sue Bridehead. Gissing is limited and Meredith’s Diana of the Crossways a Corinne type fantasy.

But Woolf never thinks of woman novelists in either of her Common Readers but the few "classics" (Austen, Bronte, Eliot). I complained on 19thCentury Literature @ Yahoo on how women authors are erased and predictably was told that did I want just men? We are certainly in no danger of reading just women from earlier eras. Predictably it was implied I want to erase men’s. Well, I certainly wouldn’t mind seeing Lawrence downgraded (and the pornographer Lolita), and also automatic elevations of a few male realistic novelists of the 1880s and 90s. Also when Woolf doesn’t even mention not one woman’s novel of the era as even challenging her three males, it’s as if women’s novels don’t exist.

I know I prefer Charlotte Smith to most of Joyce; I wouldn’t be surprized if I preferred Burnett’s Shuttle to much of Meredith and Hardy. Gissing’s another matter.

To be sure, Woolf retells the lives of obscure and non-professional writing women with moving grace, wit, and insight. I loved her lives of the gallant Laetitia Pilkington, and Jane Carlyle and Geraldine Jewsbury.

Experience is persuading me by the hour the famous and over-praised and be-prized authors in print are by no means the finest. It is really is chance, an agenda, the particular male publishers in charge at a given moment who make or erase a book.

I’ve the same complaint about Juliet Dusinberre’s book, Virginia Woolf’s Renaissance on Woolf’s Common Readers. Dusinberre makes the male authors in Woolf’s book into "honorary females" based on stereotypical ideas about masculinity and femininity. I don’t see Dusinberre having read Ward, Burnett, Oliphant, Young. A very few women whom Woolf mentions who are overpraised and super-respected (but not much read as in Madame de Sevigne).

Where are Woolf’s and Dusinberre’s women authors? The only ones about are those we read in school. She hasn’t read the women novelists of her or Woolf’s period. Probably what we see in Dusinberre combines inertia with the need to get tenure and publish. That is she’s too busying making a living to read the sort of woman’s novel she’d have to to discuss them in print. Among Diane Philips’s more revealing statistics are those that demonstrate the kind of book chosen for group reads (whether on the Net or in physical space) is not at all the type of novel women (and men) prefer to read on their own. They’ll vote for Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Teheran and then discuss issues of literary criticism far from their lives; they’ll read Marge Piercy’s Small Changes or John LeCarre’s latest male spy story on their own. On the latter it’s the fourth LeCarre novel I’ve read in a couple of years and I’ve become aware of how he deals centrally with male anxiety over female sexual infidelity (Smiley or whoever is the hero is often centrally appalled by the treacherous and sexually powerful woman he is attached to), and how they function as male comfort romances often (debunking and critiquing sharply the norms of macho male-ness). So offlist and outside groups women read women’s comfort romances and men read men’s.

The frequent disappointment of list conversations on books even when they do chose one which is close to a reader’s deepest needs (for me) is how frivolous and superficial are the subjects discussed by most of them. Not all. Books like those chosen at Booker Prize @ Yahoo demand some thoughtful serious discussion of life’s real issues and aesthetic concerns, but even there people avoid the real feelings they are working out as they read the books lest they give themselves away or (more probably) because they preferably do such working out unconsciously.

Which gets me to the second article: T. J. Clark on a new book by Bernard Anderson. Anderson is rightly famous for his "imagined communities." Clark says Anderson has a new book out which may again transfom the the thinking of other scholars. The nation-state is not dissolving away, but it’s become more and more tenuous.

Now Clark suggests that Anderson argues the new plot-design at the center of the novels that count today, the ones which win Nobel’s, Booker’s and Whitbread and Orange and other awards are not the subtle domestic story of the type Woolf intended and which the unhappy companion of Anderson didn’t have a copy. That’s E. H. Young stuff we might say; Austen material. No the big story is of marital and sexual displacement in the context of just such detective stories as Sayers and say John Buchan wrote. The latter was nihilistic, and Hitchcock made movies from his films with people who wanted only to run away. Also post-colonial and about nation-states as an imagined ideal community and power-structure breaking up. No more belief in communities that are stable; it’s all contingent arrangements which can break up any time.

Caroline and I went to Hollywoodland, a film that tried to keep the domestic disonant disquieted marital stories at the side while a Humphry Bogart or Robert Mitchum or George Smiley detective narrative takes center place. The central detective character who kept all the stories together was the fine actor, Adrien Brody. His marriage has broken up and he lives by hiring himself out as an investigator of sordid crimes and even worse his customer’s paranoid violent fantasies. The film did present women as wanting intensely to go to bed with men. Their great appetite is for fellatio and endless fucking. The women are marginalized except as bitches into trapping men or lunging at their trousers. It’s the stories of Adrian Brody and George Reeves-as-Superman (played as Ben Afleck) that count and whose subjectivity and point of view count. It is interesting to notice that the actor who is mocked and not the he-man to be admired is the be-suited ever so smoothly muscled healthy (wholesome) handsome white type, Afleck, but the darker-skinned, often filthy non-wholesome-muscled Brody.

The film was a disappointment for the core serious themes actually belonged to the broken-marriage domestic story of Brody and George Reeves, but there was a failure of nerve there. The director didn’t have the nerve to show Brody not returning to his family but just carrying on living with a woman he doesn’t much care for (nor she he) and working for a living (catching at fees). The powerful memorable scenes showed how ludicrous and caricatured were the Superman movies, how phony, with one incident where a nasty child comes up to the man playing Reeve with a loaded gun and asks if he could shoot you now. We never learn if Reeve committed suicide or was murdered by the top money-making abrasive animal-male type aging film executive brilliantly acted by Bob Hoskins. Hoskins’s acting was a recreation of his role over 40 years ago as in Middleton’s The Changeling, the villain-hero, Flores, an amoral ugly hateful dwarf who has a depth of feeling and thought just about everyone else in the play lacks. Flores takes revenge on all who scorned him. Now in Hollywoodland, Hoskins recreates the type as a fierce powerful male murderer running the studio.

According to Marion Frank in her article "The Transformation of a Genre—the Feminist Mystery Novel" (Feminist contributions to the literary canon: setting standards of taste, ed. Susanne Fendler, 81-107), the latest mystery books which are any good by women are feminist in the sense that the central story is about a woman whose subjectivity counts and who has other motives and interests beyond a man’s penis and getting tons of money and children from him. Now Maureen Corrigan agrees with this.

How this fits in with the mostly appalling women’s books (they seem to me so) described by Diane Philips in her book, Womens’ Fiction, 1945-2005 I don’t know. Reviewed by Lucy Carlyle in a not-so-recent issue of TLS (August 11, 2004, p. 31), we’re told Phillips "set out to uncover ‘a hidden history of women’s reading." The study has canonical texts for women as well as popular ones, and "she makes connections between the concerns of wome’ns fiction and its social context, providing a history not only of women’s reading, but also of the cllective female desires, interests and anxieties which their reading has expressed. Each chapter explores a genre, or a repeated plot motif, which has dominated sales of women’s ficiton during each post-war decade in both Britain and America."

Phillips includes "middlebrow" texts next to "literary counterparts"

to show how loose these categories are. Philips wants to demonstrate these categories are falsifying and there are no such distinctions in reality between pop, middle brow, or high culture. If you actually begin to read the books, you see this; or better yet there’s such a continuum and slide, the distinctions come from the framing made by publishers aiming at a particular niche’s self-image

Well, I’m not so sure. Philips’s novels from the 1980s on are awful. They are categorized as inanely glamorous "sex and shopping books," "the single woman" novel (of which a subtype is "chick-lit" stupidity seen in Bridget Jones progeny): you are measured by how many designer clothes you own still and the way women are presented is as in Hollywoodland. Philips says the high and middle brow fictions by women merge, but I can’t see any of the books I’ve read in the Booker or Orange type resembling these. Yes the 1970s "aga-sage" which appear to be about a woman apart from silly glamor objects, imagined contingent power or security, a kind of throw-back to the earlier part of the center where the woman becomes the center or mainstay of an imagined community. These are the sort of novels written by Joanna Trollope type (where she treats seriously issues like adoption) have their equivalents in the better books, and the rebellious and self-examining novels of the 60s (Marge Piercy type say) have equivalents; even the 50s books (demobbing WW2 people) have equivalents. So the cover illustration for E. H. Young’s Curate’s Wife is a much richer version of the much more cartoon-y cover of Joanna Trollope’s Rector’s Wife:

Mainie Jellet portrait on the cover of the Virago edition of Young’s 1934 Curate’s Wife

The only way I can see "sex and shopping" and "chick-lit" as having equivalents in the intelligent fiction for women today is when the Orange prize is given to a clunky epistolary book like Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk about Kevin.

So, returning to Corrigan, it would seem the basic better popular or low and middle brow book for women is the feminist mystery or the fantasy non-realistic type of Carter (say Nights at the Circus), with the descendents of realism and Woolf not popular but only high brow and rarely reflected in films. Perhaps the books have gotten worse not better because the marketplace is more driven by commercial considerations so what’s published is deliberately written to appeal to the lowest common denominator.

This debasing of women’s culture then supports or doesn’t counter the pornification of the rest of popular cultural life and its antifeminism.

And thus, at least for women readers (and Philips’s statistics demonstrate that women still buy 3/4s of the books bought in western-style bookstores today), Dorothy Sayers becomes the important mother of popular relevant intelligent novels for our era, with Alison Light’s book on the women authors of the 1930s as important as Orwell and Greene and T. S. Eliot the right view (she covers Daphne DuMaurier who wrote mystery romances too):

Perhaps. It’s a better explanation than the idea that Susan Hill’s disquieting Various Haunts of Men is a comfort book, and it connects Anne Tyler’s moving The Amateur Marriage to Elizabeth George and Helen Mirren in a TV film series about women police officers. Now Philips does not deal with spy or detective or mystery or gothic fiction (and misses much greatness in the last, e.g., Burnett’s White People).

Well I’ve meandered and thrown some thoughts out. What kinds of novels are capturing the daily realities that count to us today? when the novels are at their best? Where do good women’s novels fit in and what they’re like for real. Are there any men’s fictions which are not misogynistic (most are and cruelly so in novelists from the so-called 3rd world) and admired? Ishiguro is a rare example of a male respected novelist who presents women equally and with compassion with men. What do you think Harriet?

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I’ve been informed offblog by Bob that the actor playing the "hero" in 39 Steps was not Garfield, but Robert Donat. They look alike; same psychological type and baggage.

Jim talked of how deeply reactionary the politics of Buchan’s book was, and many such books before WW2.

Sylvia

— Sylvia Sep 25, 11:29am # - I received a good reply offblog (I get most of my replies offblog) from an old friend, Gwyn, who’s on Booker Prize:

"Hi Ellen!

Hope you don’t mind me contacting you off list, I wondered if you could tell me the name of the other book about E.H.Young that you mentioned in your blog. I have tried the TLS online but no joy – I am assuming one of the two books is: ‘Domestic Modernism, The Interwar Novel, And E.H. Young’ which is too expensive anyway although I will try the library sometime, but would like the title of the other if possible!

Take care,

Love Gwyn"

— Sylvia Sep 25, 3:26pm # - Dear Gwyn,

I like replies. I’m glad to be corrected. Now I re-look at the review I forgot to tell the titles. Looking at the review by Hardyment, there is just one book on E. H. Young. The reviewer discussed several novels by her: beyond The Curate’s Wife, Miss Mole, Jenny Wren (the Virago people chose a lovely picture by Mainie Jellett for JW too: "Girls by a Fountain").

Ah well. I’ll try to make up for it by saying there’s an excellent article on E. H. Young and other Virago novelists by Katie Trumpener, "Virago Jane," in Janeites, ed. Deirdre Lynch, and Alison Light’s Forever England : femininity, literature, and conservatism between the wars, is excellent and deals with woman authors between the wars. I don’t know if Light zeroes in on Young but she’s very good on the whole generation of women authors of the 20s and 30s.

Sylvia

— Sylvia Sep 25, 3:32pm # - Gwyn wrote again:

"Lots of interesting and thought provoking comments, Ellen! But I just wanted to quickly say how wonderful to see the name of E.H.Young mentioned more than once in any article! I am such a huge admirer of hers and think it more than time for a revival – is this the start?

Regards, Gwyn"

I replied:

With the really relentless propaganda in favor of turning the "clock" back in every direction, it could be that Young is now acceptable because she’s seen as "old-fashioned." So you find her being published about.

She’s really influenced strongly by Woolf’s novels. And I know a couple of women who write professionally about Austen and Burney (e.g., Maggie Lane) who love E. H. Young and have been trying to create a revival for quite a while.

As I say it’s the agenda E. H. Young’s novels can be used to support, the larger implications of the archetypes as perceived in the literary marketplace that will bring her back into print (if she comes back), not the actual texts or meaning of the real woman's life. For example, she lived in a menage a trois situation for most of her life.

Sylvia

— Sylvia Sep 26, 8:39am #

commenting closed for this article