Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

More on Janacek's Jenufa · 18 October 06

Dear Anne,

You may recall this past summer the Admiral and I saw and were much moved by the Glimmerglass production of Janacek’s 1903 Jenufa (from an 1890s Ibsenesque play by Gabriella Preissova, Her Fosterdaughter).

Last night Tatyana (who loves opera) kindly sent the following intelligent brief review from November’s Opera News:

"Interest in Jenufa (seen August 11), in the original Brno version (edited by Charles Mackerras and John Tyrell), centered on the direction by Jonathan Miller, who had staged another Janacek opera, Katya Kabanova, last season at the Met. In both instances, his views strayed from what the composer had in mind. This time, Miller had said during a talk before the premiere that he placed Jenufa in a Czech community in the American Midwest during World War II, so Isabella Bywater’s sets, and to a degree her costumes, looked like Oklahoma! Rocking on the front porch, Judith Christin as Grandmother Buryja could have passed for Auntie Eller, and the other characters seemed to step out of Thomas Hart Benton’s canvases. Kostelnicka’s house created the right mood of confinement, though in Act II Robert Wierzel’s even, flat, diner-like lighting banished any hint of nocturnal mystery.

Miller’s concern, however, lay not so much with the provincial milieu as with the psychology of the characters, especially Jenufa and Laca, who grow up before our eyes, and Kostelnicka, who thrashe her way to closure. Janacek’s musical imagery of country ways—thrusting outbursts, repetition for emphasis, hesitancy owing to inhibition or frustration—found a response in the director’s view of Jenufa herself as mousy, defensive and put-upon, though she is described as beautiful and "carries herself so proudly" according to the crusty Foreman of Christopher Burchett. As Jenufa, Maria Kanyova met the contradiction by singing with steadiness and assurance while acting with a mixture of fear, uncertainty and rebelliousness. Inner feelings emerged with greater eloquence when she was alone for her prayer in Act II. The Kostelnicka of Elizabeth Byrne, a bit flustered in Act I, hit her stride in the sustained outpourings of Acts II and III. It shouldn’t have been too hard for Jnufa to settle on the growingly sympathetic Laca of Roger Honeywell, vocally strong and reassuring, over the self-involved, loutish Steva of Scott Piper, who caught the character’s evasive tone. Robertson guided the score steadily toward, then through, its crisis and catharsis."

You may also recall there was a perverse reading of the opera as staged by Miller by a NYRB writer which turned back Miller’s take on the play to re-demonize Kostelnicka (see the comments in the linked in blog); a reading defended by a man on Trollope-l on the grounds Jenufa, stupid fool, typical woman who likes being punished, got what she deserved (which I placed in the comments on Jim Hightower’s progressive columns).

The Admiral read the review and comments. He had thought perhaps Miller was overdoing or being too emphatic about making sure the audience came away with a non-misogynistic understanding of what had happened, and that Jenfua was made far too innocent and saintly, but when he saw this man’s commentary he said, well some people just will never get what’s in front of or all around them (referring also to the audience response at the production we heard). Nonetheless, he still felt Miller’s switching the events from Moravia at the turn of the century to the US Appalachian area in the 1930s lost too much of the original circumstances and context, including importantly religion.

Thinking about it on and off since then perhaps the thing to keep our eyes on is how this matter of dead babies and punished and ravaged women is still central to our culture and still riveting tabooed matter as it makes visible the utter amorality at the base of what stability appears in our daily lives. I wrote a review of two books on this subject where I discussed another perenially popular text (as play, novel, and film), Susan Hill’s Woman in Black.

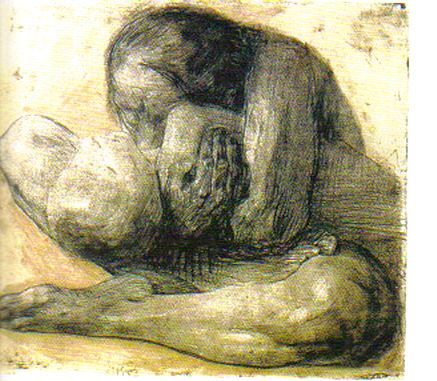

Kathe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Woman with her Dead Child (1903)

Who was responsible for the death of Jenufa’s newborn? Not just the lout Steva who rejected the baby and its mother, and not just the supposed good man, Laca who threw acid all over her face and would marry her only on condition he would not have to take the baby (left on stage at the end as Jenufa’s kind savior), but the social order that supports and honors them while marginalizing the women and making the older one into a strident anguished and then about-to-be-killed witch. A social order that today supports continual horrific wars around the earth.

What I love about Kollwitz’s art is she goes right to the heart of the matter and shows us it. I like to imagine Preissova’s Jenufa was not mousy nor defensive, but if she was, only in such a vein would she have been allowed to complain.

Sophie

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- P. S. I put the image by Kollwitz on the groupsite page of Women Writers through the Ages, and Fran provided some good URLs:

http://gseart.com/artists.asp?ArtistID=67

http://www.rogallery.com/Kollwitz/Kollwitz-bio.htm

http://gseart.com/artists.asp?ArtistID=36

I did make us a new photo album at WWTTA of Kollwitz's work and put into it images by her of the following: Raped; Outbreak; A monument to Karl Leibknecht, murdered along with Rosa Luxembourg in 1919; Pieta (a sculpture); Volunteers, Prisoners; Working Woman; [the one in the letter] Woman with a Dead Child; Death Snatching a Child; People Before the Gate; and the Memorial for their son Peter ("Burden of Survival").

Sophie

— Sophie Oct 18, 5:05pm # - Another "reading" of Jenufa: Last night I was reading John Buchan’s Crowded with Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment, Edinburgh’s Moment of the Mind.

In Chapter 3 Buchan wants to trace a trajectory from fanatical all-absorbing theocratic religions (like Presbyterianism was or wanted to be) in the later 17th century in Scotland to the tolerance and open agnoticism or atheism of the later 18th. He opens the chapter with a trial of a young man murdered by state officials (hanged) because in talk he mocked religion and said he was an atheist. He ends the chapter with Hume publishing his treatises and offices of the kirk filled with people who are coming there for a successful social career. He suggests one reason religion assumed such central importance was Scotland did not have a court and parliament so the churches’ organization filled the power gap. He shows also that tolerance was not simply a matter of growth of scientific knowledge, decency, humanity, and loss of superstitious ways nor movement away from rigid conformity and repression, but that the upper classes and powerful realized religion had been a tool or rational for rebellion.

A curious detail I would not haved noticed but the review I did of the two books on child murder and femmes fatales and Jenufa. Among Buchan’s epitomizing details for the bigotry and determined punitive behavior of the earlier religionists: in the first decade of the 18th century Edinburgh had a large number of women accused of infanticide and trials. McDonagh is not the only writer to suggest the evidence shows that most accusations were unprovable and brought against unmarried women, but the making of such accusations came out of a repressive religious framework. Hugh Jackson goes near to demonstrating how much of this material is myth. The law was framed so that a woman was assumed guilty: she had to prove the child had been dead upon birth or she was accused of child murder (if she was poor, particularly a servant and under surveillance of the powerful and not married).

So Jim’s idea that the Moravian nature of the story is important may be very sound. Then Janacek is showing us the dangers and cruelties of poverty-striken Catholic communities. And we see that a misogyny and distrust of sexuality among women extends even to the older mother figure.

Sophie

— Sophie Oct 19, 7:12am # - Another attempt by the guy on Trollope-l to disrupt the list and make me a figure of shame and contempt: he wrote a second email in which he again treated me with utter scorn, repeated my name endlessly, and basically blathered on about how he never said what I wrote about on the blog. If he wanted to argue with me he could come here where the whole of his posting appears so that anyone coming here can decide for him or herself. But he is not interested in the issue really; he doesn’t want to argue with my postings here on the blog for then he could not hurt me in a public forum.

Trollope-l is for messages about Trollope mostly, and he has never written any message on Trollope. He doesn’t read Trollope. I have removed him permanently. My sense is he resents bitterly any woman who has power and a listowner seems to him to have power.

Sophie

— Sophie Oct 19, 7:17am # - People connect opera with religion and ritual. I am wondering if the way opera is used today and since the 19th century makes it function as a deeply conservative form. Jonathan Miller tries to change this with staging the opera in 1930s US dress; other directors try to produce modern and enlightened takes on other older operas by really transforming the staging into symbolic and other avante garde and post-colonial material.

I enjoyed a Wagner opera for the first time this past spring because the director seemed to change its meaning by dressing the characters differently, having them interact on different terms, all of which were drawn from recent art film archetypes and modern novels. But many opera patrons resent this very much. They want Wagner to remain fascistic, anti-feminist.

I never understood what was going on in operas until subtitles were provided. Now I begin to wonder about the genre and the way it functions in the communities it finds audiences in. Often people with money. And there is often a connection with religion.

Sophie

— Sophie Oct 19, 7:25am # - Jill asked "Had enough of Jenufa yet?" and sent in another review:

"I finally finished the new Opera News and thought you might be interested in a portion of the interview contained therein, with Maria Kanyova, who sang the Jenufa you saw:

‘The Glimmerglass Jenufa was directed by Jonathan Miller. The common view of Miller—that he talks a good game in rehearsal, he’s smart and funny and snows the critics at press conferences, but that what ends up onstage doesn’t relate much to the opera at hand—was confirmed. It’s a Beverly Hillbillies version, with Laca as Jethro and the Kostelnicka as Miss Jane Hathaway. But when I ask Kanyova about some of the most egregious missteps Miller made, I am bowled over by the assurance with which she [Kanyova] plays devil’s advocate for the production. For example, does Miller really believe that Jenufa goads Laca into slashing her by the way she pinches and pushes him? (The libretto leaves it ambiguous as to whether it might even have been and accident, let alone premeditated.) ‘We left it with the idea that we’re not sure. What I felt below the two characters was this brother-sister kind of relationship.’

I talked with Jonathan [Miller] about showing er as a multidimensional character at that point, that she’s preoccupied with her plight [of being secretly pregnant by Steva], but on the other hand she’s still a young girl, that there was something flirtatious and fun. Why would Steva fall for her? She was very smart, if he cared about that, but she could probably talk him into anything with her wit. That’s the side of Jenufa I thought maybe the audience should see just a little bit of. That’s what I discussed with Jonathan—that she can’t be morose the whole time, we have to grow as a character to the end, to what she ultimately becomes.’

The production was poor but not debilitating. The conducting was something else – the worst I’ve encountered in an ostensibly professional situation. But I felt, as I often do, admiration for so much that Kanyova’s generation of singers does. And this time I felt something more—a paternal pride in what Kanyova, her Kostelnicka (Elizabeth Byrne, in an indelible performance, looking like a daguerreotype of a face from Mount Rushmore) and her Laca (Roger Honeywell) pulled out of thin air.

[...]

On Jenufa’s great despairing Act I call of ‘nevim’, she added a perfectly controlled diminuendo to the high C-flat, something I’ve never heard any other soprano manage, even though Janacek asks for it."

The writer of the piece is William R. Braun, who is a pianist and writer based in Connecticut.

Jill"

— Sophie Oct 31, 12:07am # - To which I responded:

On Jenufa: well it shows how people react differently. Maybe in the script Jenufa seems street-smart and wise; in the production she’s not got a malicious bone in her body and goads no one to do anything. She’s passive and serious and kind, earnest, grave. How can a woman who finds herself pregnant be flirtatious? The situation has gone beyond that. Jenufa is a Fanny Price type character (or better yet Ottilie in Elective Affinities). Steva doesn't "fall for her." He is indifferent to her. He was able to delude her into having sex with him, probably through pressure and her loneliness. It seems to me the woman writing to Miller (I knew it was a woman) is the sort who’d dislike Fanny and Ottilie. She wouldn’t want to be them.

As for the Beverly Hillbillies reference, surely this TV allusion is snide and snobbish. I took Miller to be alluding to left-wing points of view in serious plain plays by people like Clifford Odetts. Perhaps Braun has no feel for 1930s plays or the outlook.

Sophie

— Sophie Oct 31, 12:12am #

commenting closed for this article