Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

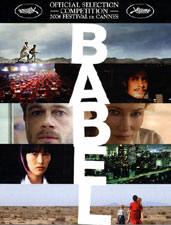

Babel: a powerful important fable · 16 November 06

Dear Harriet,

On Monday Caroline and I went to see Babel, a Zeta/Dune film based on a screenplay by Guillermo Arriaga, & directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu. Babel has been compared to last year’s Syriana because it too switches between 4 ongoing stories, and has a similar ethical-political slant. I strongly recommend you see it.

A contrast between the two films is instructive. The ethical slant of Babel’s multistory fables is left implicit, and the central triggering event which happens is not one motivated by politics. In Babel, Yussef (played by Boubker Ait El Caid), an 8 or 9 year old a young Algerian boy irresponsibly shoots at a bus and wounds Susan Jones (played by an now anorexic-looking Cate Blanchett), a white rich American woman sitting next to her husband, Richard Jones (Brad Pitt), in a window seat. Yussef has no more motive than unconscious mischief, rivalry with Ahmed (Said Tarchani), his slightly older adolescent brother, and irritation that the gun does not seem (until then) to shoot far enough to kill jackels.

This is the initiating action that drives the development of 3 of the 4 stories. The reaction to the boy’s act by the police, the governments of Algeria and the US, and the media which report the incident is a product of global politics and commercial hype and hypocrisies where the individuals who act out the policies maim or destroy the lives of all the characters who are not white, upper middle class, rich and American. The LAPD police also seem to threaten the lives of two people, a father, Kazmuna Yamane (?), and his deaf-mute teenage daughter, Haruki (Nobushige Suematsu), who are rich, upper middle class and live in American but are Japanese. The central story of Syriana is overtly politically motivated.

Cate Blanchett as Susan Jones looking out bus window before she’s shot

The use of dramatic ironic contrast is also stronger or more pointed. The 4 stories in Syriana told by Stephen Gaghan (who wrote the screenplay based on a book by Robert Baer) all occur simultaneously. The 4 stories of Babel are occurring at the same time but in many instances when we go to another story (i.e., story 3, Susan & Richard Jones’s story) we find we are at an earlier point of time than the story we left (story 2, Amelia’s) and are catching up to the moment in where story 2 begins (or story 1, Abdullah, Yussef and Ahmed’s, left off). The effect of story 3 and its ending is suddenly to bring home the irony of what we had seen at the end of story 1, and the powerlessness of the Mexican characters in story 2.

Jim said he found my attempt to tell him the stories as they emerged in the interlaced multiplot structure was confusing, and it’s best to tell him one story at a time. When you do this, you lose much of the artfulness and feel of the tale, but critics do it all the time when they write exegeses. They say they are throwing light on partial elements to understand the whole.

1:

Story 1 the most tragic and about the poorest group. The movie begins here. Abdullah (Mustapha Rachidi), a goatherd and older man with a wife and several children, has a bare hut in the plains from which his sons, Yussef, and Ahmen, herd his goats. As the movie opens, we see Abdullah buy a powerful gun from Hasan, an Arab trader (Abdelkader Bara) and give it to his sons to use against jackals prowling around their sheep. Abullah pays heavily for his mistaken giving of the gun to two children.

Yussef is an aggressive thoughtless boy who watches his sister undress from a hole in the hut, and who constantly tries to one-up his older brother, Ahmed. When the two boys fail to kill two jackals, Yussef pushes Ahmed into seeing if their guns can shoot far enough. They see a car, a truck, a tourist bus. They aim at the latter and we see it stop in the distance. Only three sequences later do we realize an American woman named Susan Jones (Cate Blanchett) was badly wounded.

The three other stories begin and when we get back to Algeria, we see the police ruthlessly and cruelly beating the old Arab man, Hassan, who sold the gun to Abdullah. They are shamelessly vicious to him, tie him up and beat him, humiliate his wife. They think he tried to murder the American woman or knows who did. This is the first of many scenes in the movie where we see a low ranking police officer or gatekeeper of some kind brutalizing, insulting, and outrageously abusing his office when the people he has authority to question or stop or whatever are not upper middle class American people. Only upper class white Americans are apparently wholly immune, for the Japanese businessman has been intimidated by threats and treated badly in the past when his wife committed suicide (he was immediately suspected as the killer and accused).

A few sequences from the 2nd, 3rd and 4th story and we see the boys hear on the radio and TV that a woman names Susan Jones has been murdered by terrorists. They recognize the bus, and the place photographed in the news show. They know it’s them and hurry off to bury the rifle in a hole in a cave. This is the first of a number of scenes in TV where we see some aspect of the terrible goings on that result from the shooting of Susan Jones; we hear much pious regret and lurid titillation and then the news show moves onto the next. The lives in this photograph are fodder for the material between the hideous TV commercials we also see unravelling.

The police have beaten Hassan to where he says Abdullah the man he sold the rifle to lives. They go in a cortege to the mountain misery. On the way they see Yussef who lies about where his father is, and he lies, they get lost, return to Hassan to beat him some more, and then hustling Hassan’s wife in as a hostage who must tell them where this hut is or they’ll kill her, they go again to the same hut. By this time we have seen the scene where Abdullah’s sons are driven to tell him what happened from a news report, where he cries why have you destroyed me this way, where he flees with them up the mountains, and we see in the distance the police cars roaring near. The woman in the car sees the goatherd and his sons and point them out.

They ride over and begin to shoot at the man and his sons, shooting to kill. The man terrified hides by a rock with his two sons. Ahmed panicking tries to run and is shot. Yussef grabs the gun and begins shooting back, the father grows hysterical, and the police murder Ahmed. Yussef then breaks the rifle up on a rock and throws his hands in the air and runs down to the mountain crying he is the murderer, his brother and father did nothing, and they should kill him.

As he runs down there is a moment where the head of the police realizes the culprit was an irresponsible boy and looks dismayed. We are to see the police officer will not murder Yussef, nor even beat him senseless probably and surmize the police will leave after perhaps roughing up poor Abdullah whose life is forever traumatized by the loss of this older son. Yussef too.

The image at the top is of the Abdullah and Ahmed fleeing

2:

Story 2 is of the destruction of the career and place to live quietly and independently of an illegal immigrant Spanish woman, Amelia (played by Adriana Barraza). Her story begins second. As the story begins she is on the phone with her employer, Senor [Richard] Jones (Brad Pitt); he will not give her tomorrow off to go to her son, Mike’s (Nathan Gamble) wedding. Senor Jones is travelling with his wife and there has been an accident (we realize the man on the phone was on the bus we saw in story 1); the Senor has to call his sibling but he doubts this sibling can come over tomorrow. There’s nothing he can do about this. He’s sorry but that’s that; Amelia can’t go. Amelia puts his 5 year old son on the phone who tells his father his big achievements in school; the boy is puzzled because his father is upset but Amelia works to soothe him.

We see her spend the night coddling and mothering these children. Every moment of her existence is given up to them or the house. She tries hard to find someone she trusts to take her place so she can go to her son’s wedding, but no one else can get off or dares take the children in for a few hours. So she takes them with her to the wedding.

Her nephew, Santiago (Gael García Bernal), arrives in a car. He says leave them behind because somehow we may get into trouble as they are white children. She says she cannot leave them and refuses to hire someone she doesn’t know well. They cross the border over to Mexico.

A few sequences later and we see her very happy to see her son. The wedding is one which cost little: it’s held outdoors in a huge rackety place with many chairs and tables. A terrible band 50s style is there. The son is dressed to the nines and does not look like a magazine at all; his heaviesh perhaps pregnant bride, Debbie (Elle Fanning) is overdressed and has an absurd crown. Santiago is kind to the white children and soon they are entering into the party in its spirit. Everyone has a good time and is happy. Dancing, drinking goes on late into the night. Amelia flirts with a salacious persistent drunken older man, maybe has sex with him in a back bedroom.

Dissolve and it’s now very late, Santiago is drunk. Amelia’s son urges her to stay the night but she fears not coming home and not getting the boy to his soccer team practice.

We see Santiago is too drunk, but he tries to go a shorter way to cross the border and when they attempt this things go suddenly very bad. The officer is a bully thug white man (Clifton Collins Jr.) who behaves analogously to the Algerian police. What is this woman doing with these white children. He speaks to them like cherished creatures. Where is her letter of permission to have them. She is not biologically related. He is rude and insulting to Santiago and after abrasive roaring commands and insults and refusals to explain himself, he demands they drive over to a spot where it’s clear they will be bullied, harassed, and who knows, shot. The man has a gun and is itching to use it.

As Santiago drives over he suddenly U-turns and goes driving frantically into the desert, and soon the police are in hot pursuit. Santiago near misses a couple of head-on crashes getting round huge trucks.

Santiago grim before his windshield in his car just before he steps on the gas and flees

Amelia is hysterical. She would never have talked back at all, but we see that would not have done her any good. She is not respected and is treated like a distrusted animal. Santiago drives off the road deep into the desert and the police drive by. He insists Amelia get out with the children; he drives away and that’s the last we see of him. We are to assume he got back to Mexico and whatever happened there he was not killed. She tries hard to walk with the children to the road center but they are too heavy and she is bewildered so she leaves them.

She does get to the road, and signals a cop car. A black cop (Jamie McBride) gets out and treats her terribly. He has no compunction to hit and push her harshly. Handcuffs her and insults and berates her, but he does listen enough to know two white children are somewhere in the desert. We see him drag her away to a car filled with imprisoned Spanish and poor people.

We return to the other stories. When we come back she is in a chair being insulted by a fat white man, an immigration official. He berates her for leaving the children to die. He will not listen to her story of how she has spent her life bringing them up. They are not biologically related to her. She is being deported. She thinks to ask for a lawyer and he threatens her and then tells her it will get her nowhere. Big man tells her the children are safe. She cries and talks of how she had built a life for herself for 16 years. He sneers. He says her employer has agreed not to press charges though he was very angry at her when told what had happened.

The last we see of Amelia she is exhausted, still in the expensive red dress which is too tight which she was uncomfortable in to start with but was appropriate, and she wore with her high heels through her desert adventure. She is stumbling on a sidewalk in Mexico and her son runs up and hugs her, and is taking her back to his small house. Unlike Ahmed, she is alive; unlike Hassan, she has not been physically horrendously beaten. She has lost all her things.

Amelia trying to save herself and the child walking in the desert

3:

Story 3. We see an upper middle class white American couple in a make-shift elegant restaurant in a tent somewhere in a desert. They are bickering and the wife, Susan Jones (Blanchett) is bitter; she does not know why they have come to this miserable place. He says to be alone; she looks around and sees all the tourists in the tent with them. It seems he may have had an affair and he wants her to forgive him and has taken her on a trip to appease her, a trip she didn’t want (but perhaps he did). She wants non-fattening food; when the proprietor says nothing has fat in it, she shrugs and orders a diet coke while Richard (Pitt) orders a full meal.

Dissolve and we now see them on the bus and they are beginning to get a little companionable and suddenly the two shots ring out and she is badly hit. She is bleeding profusely and in severe pain. The people in the bus run about in it hysterical; there is a bullying white male type with an Australian accent; there are British people with plummy upper class accents. No blacks on board, no Spanish, no middle eastern people, perhaps one or two Asian-looking people. They shout terrorists and think they may be killed. But nothing more happens. We realize we are seeing what happened in the bus as it stopped and the two boys, Yussef and Ahmed looked down.

The busdriver’s helper, Anwar (played by Mohamed Akhzam) tells Mr Jones his options: a hospital at least 4 hours away is the best but she may bleed to death before then. Twenty minutes is his village where there is a doctor. Mr Jones demands in rude terms that the driver take the bus to this village, and over the protests of the other passengers who do not want to turn round or change their route, the bus is driven to this dirt-poor desperate village and finally a dark cave like hut. Here Anwar lives with his wife, several children and grandmother (Sfia Ait Benboullah).

The grandmother is toothless, aged, ugly, ignorant of western learning. She is left to watch Mrs Jones while Anwar seeks the doctor who is a vet (Hammou Aghrar). This vet tells Anwar that the woman may not die as her spine is not broken but her clavicle is; if he does not stitch her wound she will bleed to death very quickly. Anwar at first mistranslates to a more cheerful prognosis but Mr Jones doesn’t believe it, and he sees the doctor readying a long needle (putting it to a flame) and thin steel-looking thread. Somehow the message is got through they must operate by stitching the wound. Susan awakes. She grows hysterical and begging when she realizes there will be no anesthesia. They hold her down and proceed despite her howls.

[Cate Blanchett is at least 20 pounds thinner than the last time I saw her (in Shipping News; in another film as Katherine Hepburn); she now has such a thin face I could see the lines of her jaw arch as she talked . In the scenes where you see her lying on the floor that night wrapped in a blanket after her wound is stitched, she literally resembles a bag of bones.]

A few sequences later and we see the husband fighting with the Australian tourist who is leading the others to say he has 30 minutes and if the ambulance doesn’t come they are leaving. They are thirsty and uncomfortable. He gets to the one phone in the village and calls his relatives—not the American embassy. Only later does he call the Embassy. We see him begin to be rude and shout and nag that he has the right to an ambulance and where is one. He is told by a lead villager that this incident has made the Algerian government uncomfortable; they are being accused of harboring terrorists and feel threatened. Many hours go by and there is no ambulance. (Joke alert: perhaps there is only one in that part of Algeria and it broke down?)

A few sequences later and still the ambulance has not come. The old woman is feeding Susan deeply in pain opium from a dirty old home-made pipe. Susan is grateful. Richard is grateful to Anwar for the hot tea in the morning. Anwar and he talk in the night and Anwar says Richard should have more than the two children Richard showed Anwar photos of. Richard asks Anwar how many wives Anwar has, and Anwar says he is too poor for more than one.

A couple of sequences later and we watch the bus drive away leaving Richard and Susan in this backward half-starved village. Then a gross heavy military heliocopter is seen coming in. It lands in a cloud of dust endangering the villagers and their huts. A make-shift wooden stretcher is got together and some male villagers, Richard and Anwar carry Susan to the helocopter. She’s still alive but looks very bad. The point is made that all that is available to help people in this emergency is military equipment (meant to carry bombs, to survey, to bully).

Before getting on, Richard tries to shove a fistfull of bills into Anwar’s hand but Anwar refuses. What can he buy? The aircraft rises and takes the couple high in the sky, and we next see Susan in a modern style hospital trolley, with IV, being trundled off past a glass door that Richard is not allowed to pass.

He waits. A modern physician in white coat emerges. They must operate. She is in danger of losing her arm. She has been bleeding internally badly. He slips back. It is revealing of the powerlessness of this couple as an individual couple that Richard has no ability to pass those glass doors.

Now he phones home and talks to Amelia. Now he tells her she can’t go to her son’s wedding He breaks down and weeps uncontrollably when his son is on the other end of the phone. We are where the second story began.

Richard Jones weeping at the hospital phone

Susan Jones turns up in the one TV in the village on the news more than once and in the fourth story (just below) repeatedly. When last seen we see them on TV in the fourth story. The reporter tells of how all is now over and the couple is having a "happy ending" and we see a politician who is a Bush-type in looks (but not him) greeting them as they come into an airport in Calfornia.

4:

It takes some time before we realize how the fourth story is related to the other three. It opens on a deaf-mute Japanese teenage girl, Haruki (Nobushige Suematsu), playing with a team of deaf Japanese girls in a volleyball game. They lose and are sore losers. We see them in the locker room and Haruki goes off with her business-man father (whose name I don’t know). We see them in a car and she acts nastily to him; we see she is raw with anger and resentment, and it seems at first her father may have divorced her mother. It turns out that the mother shot herself through the head some time ago, and left these two people with no one else in the family in their apartment.

A series of sequences shows Haruki is a troubled young woman; she repeatedly behaves in a self-destructive shaming and reckless way. When she and her Japanese girlfriends are snubbed by a group of Japanese boys once the boys realize she and her friends are deaf, she takes off her panties and exposes her vagina to them. When she goes to a Japanese dentist, she tries to get him to put his hand in her vagina. We see her taking pot on the street. We see her with a friend in an awful club. The director now and again shuts the sound of the film off so we can feel how she is experiencing the world: silence. I won’t detail all this: suffice to say it’s miserable, mean and nasty sex; at least unlike a movie I saw sometime back where we were to be amused at the cruelties and sordidness of teenage sex, here we are to see how degrading and demeaning it is.

We also see how a disabled person is easily twisted by society: Haruki’s problem is not so much that she’s deaf; she has become dysfunctional because of the reaction of hearing people to her deafness and her mother’s death (itself attributed by implication to the anonymous lonely routeless existence the woman led in apartment they have on whose door is a huge combination lock).

That this is the perspective comes clear when a Japanese young police officer Haruki is attracted to comes to her apartment. She first goes out on the balcony of this apartment and we see it’s an expensive flat in very tall building in the midst of the most citified part of LA: all high buildings lit with neon at night like in a cavern. It’s scary to me. She assures the officer that her father did not kill her mother but her mother jumped off the balcony.

The connection to Stories 1, 2 and 3 is Haruki’s father, the Japanese businessman gave the rifle as a gift to Hassan, the Arab trader who also runs safaries for rich tourists. The girl called this young Japanese police officer because in the second sequence of the story she had been approached by him and an older Japanese policeman who wanted to question her father. The young man says the police were not going to question her father about her mother’s death. She then goes into a room and emerges naked. He is appalled and at first attracted, and then realizing he could get in trouble (lose his job) if he uses her and also feeling pity for her, we see him through gestures show sympathy and pity, and she bursts into tears. He leaves her after that and promises perhaps to see her again.

As the young Japanese police investigative officer comes out of the elevator, the father comes in and they talk. The father too seems to suspect the police may want to interrogate him again over her mother’s suicide (the police had given him a hard time), but it turns out that they had the serial number of the rifle that had damaged the American woman and wanted to ask the businessman if he sold the rifle to Hassan. We are aware a great deal of money and communication has gone on to find the businessman. Far more than was spent to provide services for Susan Jones herself.

The Japanese businessman sensing he might be accused of supplying guns to terrorists, says no and then very respectfully explains. He was on a safari, and wanted to show his gratitude to the excellent benign guide, Hassan, and knew American money might not be helpful. He looks worried and asks if Hassan is okay. In this story when we saw the Jones case whizz by on TV the announcer says a hunt is on for the man who sold the rifle to the Arab terrorists. The young police officer says he does not know if Hassan is okay. We last saw Hassan being badly beaten by the vicious police.

The story line or action of Story 4 is not generated by Yussef’s shooting of Susan Jones; but its denouement is. One of its fascinations is that these Japanese people seem to live in a self-enclosed environment of all Japanese people in the midst of LA.

The story of Haruki and her father ends the movie. We see the father go upstairs, and hug the daughter on the balcony. They look so small against the rest of the city as the camera provides a long shot. The point here is these 4 are but 4 of a million stories all over the globe and this place, LA, is as inhumane place to live as Abdullah’s in Algeria.

Haruki’s businessman father’s sombre face

The method of the movie is utter realism of the type I saw in the 1990 film adaptation of Mansfield Park, Metropolitan and last year’s wrong Oscar-winnder, Crash pretended to have but didn’t. All the talk is real, and all the incidents feel utterly real. The camera work is often hand-held and the scenes work inconsequentially with the drama seeming to come by chance (it’s not).

The point of the film is much of the world lives in misery and at risk from the militarist totalitarian style government the US supports. Inside the US only the upper class whites seem safe from this kind of beating and demeaning and loss of dignity and rights. Their personal safety and health is of no concern to their government of course. Outside the white cocoons which is shared by the groups of people who make as much money (the Japanese enclave Haruki lives in), everyone is continually unsafe in public space from the middle and upper-level thugs given these thugs’ authority to destroy and beat and maim and insult anyone if they can be suspected and then found to have broken any law. If they look suspicious, they had better be docile.

I have experienced this at airports and being white there doesn’t matter if you are not paying for a luxury seat.

Don’t miss this film, Harriet. It’s on the level of the 2003 German film, Goodbye Lenin, in depth and relevance to us today.

I should say the audience in the Cinemart room where Babel was playing was tiny. I could see they were affected. A man, white, a stranger, actually said to me, "weird" I replied it was excellent and he had a sudden look of resentment on his face. A middle class older white woman asked me what I thought and I said "excellent," and she waited until I got out of earshot to tell her friend she thought the film was "nothing" and yukky and "stupid." Maybe they didn’t understand it because all meanings were implicit and there was no heightened drama in the individual scenes except when a natural crisis arose, but I think they did get it and resented or wanted to and would erase its meaning from their minds. I’ve seen my mother do the same many times. Perhaps this will be the common response.

This "understand no evil" attitude helps explain why the US government and its henchman and supporters around the world and in middle level bully jobs get away with it. And why the world is organized in such a wasteful cruel way for most people.

At some point all the major characters broke down and wept, sometimes quietly, sometimes desperately, sometimes uncontrollably. Babel is however not an emotion picture and except for the slightly upbeat ending not melodrama.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Corrections:

Story three. He didn’t have an affair, though it seems so at the beginning. Their youngest child died from SID. This is first talked about in story two ("Amelia, don’t turn off the light. I don’t want to die in my sleep like Sam." "oh honey, you won’t die, no. That just happens to young babies.") and then confirmed in story three during the scene where Pitt helps his wife pee in the pan they start talking about how they miss Sam and how angry and hurt they were when he died, and how they’re already forgetting what he looked like, etc.

Story four: they’re in Tokyo. Not LA. makes more sense that they’d be isolated surrounded by Japanese people, huh? The isolation from the rest of the world on their little island and seeing it through tv was a good observation though.

— anibundel Nov 17, 9:27am # - "Dear Ellen,

This sounds excellent.

Kathy"

— Sylvia Nov 17, 8:30pm # - From Pam, on Progressive Thinkers @ Yahoo:

"I haven’t seen Babel yet, but I just saw Fast Food Nation today.

I highly recommend it. I had read the book and couldn’t imagine how

that could be translated into a movie. But Schlosser (author of the

book) and Linklater (co-script writer and producer) have made

something strangely powerful. Instead of a straight documentary,

they used a series of interlocking, fictional stories of people

affected by or involved in different phases of our fast

food/throwaway culture to paint the larger picture.

Is there anyone else here who has read the book or seen the just-

released movie?

Pam"

— Sylvia Nov 19, 8:00am #

commenting closed for this article