Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Erasing Louise Labe · 14 December 06

Dear Marianne,

A couple of days ago on Wompo, Annie Finch, the published translator of the sonnets of Louise Labe (her and Deborah Lesko Baker’s book is one in the series of prestigious volumes published by the University of Chicago Press), told us about a book written by a Frenchwoman, Murielle Huchon, Louise Labe: creature de papiere, where Huchon claims there was no such person as Louise Labe. No, people who study and read her poems have been (delicious, isn’t it?) the dupes of a mischievous hoax for 400 years. These extraordinary sonnets were produced by a collaboration of males. And who does this name, Louise Labe, belong to? A prostitute. You could have guessed that, couldn’t you? The snobbery of the dismissal also marks this as another outbreak of the people dismissing Shakespeare’s existence—dubbed by Jim Oxfordians.

Annie wrote: "As this writeup explains, Labe has long been a feminist literary beacon … an outspokenly passionate, direct, and brilliant poet. She also said "I still haven’t had the courage to look again at Labe, with whom I developed a deep womanly communion over the 6 years I was translating her, and imagine the possibility that these word were not written by a woman after all. I’m working up to it.. . (:" So onlist at least Finch seemed to take such a claim seriously!

A very postive review online of Finch and Deborah Lesko Baker’s book by Leah Chang, says that Finch translated the poetry aright (in my view) creatively:

"Finch’s translations are indeed beautifully crafted and dynamic. If, at times, some of her vocabulary choices determine meanings that the original French leaves more ambiguous, she nonetheless captures thoroughly the sensual passion and the startling modernity of the poems. Perhaps the most controversial element in the translations is Finch’s addition of titles to the English elegies and sonnets."

I do not own a copy of Finch and Baker’s translations, but can supply two of the most frequently-reprinted sonnets as translated by Graham Dunstan Martin for the Edinburgh Bilingual Library:

No. 18.

Baise m’encor, rebaise moy et baise:

Donne m’en un de tes plus savoureus,

Donne m’en un de tes plus amoureus:

Je t’en rendray quatre plus chaus que braise.

Las, te pleins tu? ca que ce mal j’apaise,

En t’en donnant dix autres doucereus.

Ainsi meslans nos baisers tant heureus

Jouissons nous l’un de l’autre a notre aise.

Lors double vie a chacun en suivra.

Chacun en soy et son ami vivra.

Permets m’Amour penser quelque folie:

Tousjours suis mal, vivant discrettement,

Et ne me puis donner quelque contentement,

Si hors de moy ne fay quelque saillie.

kiss me again, kiss, kiss me again;

Give me the tastiest you have to give,

Pay me the lovingest you have to spend:

And I’ll return you four, hotter than live

Soals. Oh, are you sad ? There! I’ll ease

The pain with ten more kisses, honey-sweet,

And so kiss into happy kiss will melt,

We’ll pleasantly enjoy each other’s selves.

Then double life will to us both ensue:

You also live in me, as I in you.

So do not chide me for this play on words

Or keep me staid and stay-at-home, but make me

Go on that journey best of all preferred:

When out of myself, my dearest love, you take me.

No. 19.

Diane estant en 1’espesseur d’un bois,

Apres avoir mainte beste assenee,

Prenoit le frais, de Nynfes couronnee:

J’allois resvant comme fay maintefois,

Sans y penser: quand j’ouy une vois,

Qui m’apela, disant, Nynfe estonnee,

Que ne t’es tu vers Diane tournee?

Et me voyant sans arc et sans carquois,

Qu’as tu trouve, o compagne, en ta voye,

Qui de ton arc et flesches ait fait proye?

Je m’animay, respons je, a un passant,

Et lui getay en vain toutes mes flesches

Et l’arc apres: mais lui les ramassant

Et les tirant me fit cent et cent bresches

Many a stag Diana hunted down

Among the thickets, then beside a stream

Rested among her crowd of nymphs, her crown.

And I went dreaming, as I often dream,

Unthinking, when a sudden voice addressed

Me saying, ‘Wide-eyed Nymph, the path you’re on

Will never lead you to Diana.’ Then,

Seeing my quiver and my bow were lost,

‘Companion, on your way what did you find

That stole your weapons from you ?’

‘I took aim at someone passing by me,’ I replied.

‘Every last dart I cast and after them

The bow as well; he picked them from the ground

And shot; and every arrow made a wound.’

For me everything about both signals a woman, "l’ecriture-femme," from the angle the first is written at, and the tone of verbs like "don’t chide," to the use made of Diana, though in this one we have the poet identifying with the goddess (the more common connection is Diana has betrayed a member of her own sex). Mary Sidney, Lady Wroth writes in just this vein, and from the same stance, only intensely guiltily, with profound shame and self-denigration. Aphra Behn both exults and is paralyzed.

Marilyn Hacker, another published poet (well-known in her circles), who lives in paris, told us about the literary talk in numerous French literary reviewers, publishers and critics worlds:

"I believe the book posits Pernette du Guillet as a fake too.

It was greeted with positive smirking glee by French male literary critics. "Exit Louise!" finished one review.

I confess I haven’t yet read Mireille Huchon’s book – despite there not being a language barrier – because, for me as for Annie, the ramificationsare too depressing. To those who say "are the poems good ? That’s all that matters" – imagine, in two hundred years, someone producing a bookpurporting to prove that, oh, Carl Van Vechten, Noel Coward and Nancy Cunard had actually written the poems of Langston Hughes collaboratively, and the "real" Langston was a street-corner no-account. Even this wouldn’t be QUITE as much of an historical slap in the face because there are so many African American poets of indisputable accomplishment contemporaneous with or in the generation following Hughes . No one could take such a thesis as proving anything about African American literary genius in the 20th century. Whereas … (Examples of major women poets in France are very few and far between. Mucn more than in Germany, Spain or Italy, poetry in France remains a male preserve—so the ramifications of this erasure would not be minor. )

There have been, as someone said, hundreds of literary fakes and impersonations throughout the history of literature. But, apart from endless speculations on Shakespeare – which are something of a sport, and none has ever wiped the Shakespeare persona from the canon – has any one ever persisted for four hundred years or more ? Most were discovered and ‘outed’ within the century, if not the decade. Huchon is not the first quailfied scholar to write about Labé; Labé isn’t a recent discovery.

If ‘Louise Labé’ were the invention of a group of male poets as garrulous and, at times, querulous, as Clément Marot, Joachim du Bellay and Maurice Scève and – who else was supposed to be in on the hoax? Magny? – is it likely that they all kept the secret to their deathbeds and beyond? That there was never a whisper, a hint in a letter, a quip in a will, that these well-circulated, well-praised poems were their own production? This wasn’t a religious or political matter, after all.

Apart from one vituperative letter calling Louise a "common prostitute" (I believe Mary Wollestonecraft was called the same), even the suggestive insults are more in the "courtesan" direction. Et alors? Gaspara Stampa and Veronica Franco were courtesans; I believe that musical performance and composition in the 15th and 16th centuries were often the province of courtesans. The only sort of biographical fact that might testify against the ‘historical’ Louise as the author of the poems with which she’s credited would be proof of her illiteracy. She would not have needed to go to university, or to read Latin, to have written poems in the popular tongue.

I’m only waiting for a good book or essay by a 16th century specialist (a Labé specialist like Karine Berriot) to counter Huchon’s thesis. "

I then wrote:

Having some spent time myself reading and rereading these sonnets (and a couple of critical studies) and translated a few, I too cannot accept the idea they were written in collaboration (not common in poems, though common in plays or books where you can divvy up chapters and acts). To me they are like Gaspara Stampa’s, only more aggressive, stronger, more archetypal and far fewer. She differ because her poems are areligious (and that’s why she appealed to me).

We should connect this to the rank-based hierarchical family systems of powerful people as well as the position of women. It’s parallel to the persistent reiterated belief Shakespeare could not have written his plays and substitute for him an aristocrat. Labe was not a high ranking women from the stories told about her. I put it this way because (as with Stampa and other unconventional women), there are problems in the biography. Anyone reading it easily recognizes extravagant stories presented as reality, such as she fought on horseback in a famous battle supporting some famous numinous male. Facts about her are thin on the ground and her poems (unlike Stampa’s) do not add up to a detailed story (and other sonneteers’ poems, do, e.g., Philip Sidney and Mary Sidney Wroth).

She was not respectable in the way women are required to be and so lies were told, truths omitted, a strong silence kept here and there. We should remember how strong a taboo was broken when a woman wrote poetry of passion which suggested she had a sexual appetite she satisfied. To present yourself as a non-virgin before marriage or unchaste was dangerous. Teresa Guiccioli maintained to her dying day that she and Byron never had sex (her 700 page book on Byron has just been published and it was probably not destroyed because her second husband was personally proud to tell of how she had been Byron’s mistress—for which he is never mentioned but to be laughed at). Any woman writing such poems had to cover up the realities under the metaphors. I’ve seen that in Veronica Gambara’s poems and the modern edition repeats the discreet omissions and makes no obvious connections (lest the still living family be offended).

That it’s hard to come up with hard biographical facts is not unusual for this medieval era for men below large property-owners too.

Vittoria Colonna will not be erased because she was a member of a powerful family who are still central to Italian politics (it was a male Colonna who had the task of personally informing President Roosevelt Italy was at war with the US). Veronica Gambara’s real story cannot come out because she too was a member of a clan (less powerful); so you can’t erase her as the author but you cannot tell the real story of her life as reflected in the poems.

In her book, Carol Pateman argued that women still connect to society where it counts through men: father or brother, husband, the son, the male lineage clan. Women being secondary unless they are part of such a clan biologically (and thus seen as owned, part of the identity of those who count) are again dismissable.

Shakespeare was not part of such a clan; Oxford (the favorite

candidate still, and a total shit by the way) was. In the 16th-17th

century players were categorized with vagabonds (Colette wrote a book about being a vagabond because she left her husband and wouldn’t take up with another man through marriage so she’s a vagabond), vagrants, criminals and had to register themselves as groups with a patron (powerful male, propertied, money, member of a clan). Labe’s husband is said to have been a rope-maker. A tradesman. A nobody.

Characteristically somewhat defusing the issue and also bringing up the real philosophical aspects of the problem of making a fetish out of the name given to a poet and focusing on the life of his or her supposed life, and using the poems as elements in identity politics. Annie also wrote:

"Funny, the whole question of computer poetry raises questions that intersect interestingly with the Louise Labe question. For example, if there were a computer poem that was emotionally moving, a ‘good’ poem, would it be as appealing if you knew a human didn’t write it?

These would be some pretty interesting psychological studies. We’ve done one or two on wompo in the past—posted poems without the gender of the authors and had people guess."

Yes, after all, are not all great poets the creatures of paper? Yes, we know very little of the woman who left 22 extraordinary sonnets in French which appeared in 1555. And so? She had a lover or lovers. And so? And yet we have to admit it’s important who wrote a poem. Leah Chang opens her review thus: "In the last twenty years, Labé has become increasingly central not only to scholarship but also to undergraduate and graduate teaching of the French early modern period." One result of this erasure of Labe’s identity as a woman poet who was a recognized member of a respectable group of Renaissance poets is the attempt to deny the existence of Pernette du Guillet too. And where will this stop?

For Huchon this makes her book important, gives her prominence and also positions her against feminism. Such a stance has helped Helen Vendler become the female doyenne of English poetry. She scorned Margaret Homan’s book arguing for a woman’s poetry as such (in the New York Review of Book) and never stoops to contextualizing women’s poetry with that of other women—when she writes of women’s poetry, which is rarely, and only about "stars" (e.g., Emily Dickinson, shorn of the aspects of her poetry which she shares with other women).

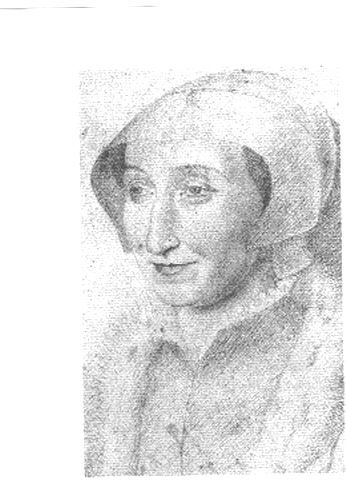

It was probably a man who drew the engraving that has been placed on many a volume containing Labe’s poems. If it was a woman engraver, she would have been subject to the way her publisher would want her to present Labe. At any rate, the traditional engraving (found on the Librarie Droz edition of the poetry by Enzo Guidici) gave the woman poet a sly eye.

I would have and still would give her a candid extraordinarily intelligent one, something in the vein given Marguerite de Navarre in the engravings we have of her.

Hacker’s apologetic tone towards women’s poetry of earlier eras and her implicit idea that while modern African-Americans have made good their claim to write good poetry, women have not bothers me. Huchon furthered her career and made her book important. The real harm she does goes further than people beginning to apologize for believing in Labe and Guillet; it strikes directly to the repeated and apparently seriously taken idea that women can’t write good poetry except a few rare exceptions. And then we hear it for the virgin, Emily Dickinson, no prostitute she, stayed in her room in white, or the upper class complict mostly silent surviving women—anthologies of earlier women’s poetry are still dominated by aristocrats and it’s not just that their poems survived more.

Elinor

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- A few more comments from Wompo on this controversy:

"Can’t believe people are taking the erasure of Louise Labe so easily … it seems like people are so ready to say "Oh! well, she was implausible anyway. " I’m implausible and so are you … and so are they.

I wonder that no one on the list has pointed out that Sappho too was really a man…

So far I have felt too hotheaded to answer this. But I will, on-blog.

Argh!

– Liz"

— Elinor Dec 15, 12:13am # - Laura K wrote:

"Ellen (my friend and she knows it) wrote .

No no no. This is just one poet. As women we don't want to be pandered to or to live by lies. We really want to know what really happened. But even greater wrong is done, to shoot the messenger (Huchon)--especially because she is a woman. She's done some serious work, no? We should respect that and not attack her and impune her motives.

Labe isn't Santa Claus and there's no point in not acting like grown women who have confidence in ourselves and our own work. If people say silly things, such as that about Dickinson--whose virginity we can not really attest to and anyway so what?--

And there can be many reasons why things hundreds of years ago didn't survive. Or reasons why women (such as the women of 17th-century Venice) turned to music instead of poetry (they could support themselves better by it for one thing--I'm thinking of Vivaldi's school, or rather where he taught). And of course only upper classes wrote; they had the time--true for men as well (except for show biz types, both male and female)."

To which I responded:

My view rests on time spent with the poems themselves translating in the context of studying and translating other Renaissance women's poems. The argument from the period (no one at the time doubted it and anti-feminism was rife then -- the controversies over Christine de Pizan are pertinent here) and from the 400 years of acceptance are good, but really finally it's the poems (though I wouldn't ignore the obvious results to the scholar -- Potter Stewart was accurate when he said look to the results in a famous supreme court decision).

E.

— Elinor Dec 15, 12:16am # - Fran remarked on WWTTA:

"I remember the French-Swiss professor whose course on Labé and other Renaissance writers I followed a couple of years ago mentioning various theories on her identity and contestations of provenance, but she didn’t seem to doubt there was a real Labé writing. It would be interesting to ask her opinion of the book if I could still get hold of her – she’s since changed universities and gone back to her more congenial Lausanne.

Fran"

— Elinor Dec 15, 12:52am # - On WWTTA Anna F. contributed some of what’s being said in French venues:

"I just looked into this Labé business.

It turns out that Mireille Huchon is the author of that book. She is the head (directrice) of the French department at the Sorbonne, and specialises in grammar and linguistics of old French, middle French and modern French, and Medieval studies, so, big calibre..

It also turns out that the people who support her theory, and find it wonderful are all the French academics, such as Marc Fumaroli who wrote an article for Le Monde in May. I include it here, it’s only available if you pay for it, so I just pasted it at the end of this email. I also pasted an article from the other big newspaper in France, Libération.

I also found three other texts that would be of interest for you, one by a feminist ( http://poezibao.typepad.com/poezibao/2006/05/carte_blanche_a_1.html ), and one by an academist who dissects the book, and gives extracts (http://www.fabula.org/revue/document1316.php )

And two more things: Louise Labé was a courtisane, and it’s her father who was a rope-maker (cordier)...

The reason why I posted these is not because I adhere to Mireille Huchon’s thesis, but just because I thought it would be interesting to read the

French criticisms..

Anna

~~~~~~~~~~

Article du Monde

Louise Labé, une géniale imposture

article paru dans l’édition du 12.05.06

Il en va de la poésie comme de la peinture. Il ne suffit pas qu’un peintre (Titien, Ingres ou Girodet) ait prêté son art à une belle nudité féminine ou masculine pour croire que ce corps déshabillé se doive de faire le même effet qu’un vidéo porno. Il ne suffit pas non plus qu’un poète (Catulle, Pétrarque ou Proust) évoque une fictive beauté cruelle pour croire qu’il raconte, en langage « codé », sa torride vie sexuelle, laquelle, « décodée » par les exégètes et traduite en médiocre prose par les biographes,dispensera leurs lecteurs naïfs d’entendre le message original. Peinture ou poésie, l’art retors a ses détours auxquels le réductionnisme décodeur ou biographique substitue des raccourcis.

Savante, mais ne s’en laissant pas conter, sorbonnarde, mais non philistine, Mireille Huchon, dans son livre Louise Labé, une créature de papier, lève le voile sur certains détours de l’art négligés par « décodeurs » et biographes. Spécialiste de Rabelais et du « beau XVIe siècle » français, Mireille Huchon rejoint les conclusions auxquelles sont parvenus les meilleurs connaisseurs actuels, un Paul Veyne, un Philip Hardie, de ces élégiaques grecs et latins que les doctes (mais facétieux) poètes de la Renaissance savaient par coeur et imitaient en connaissance de cause: leurs « cris » mélodieux de colère, de jalousie, ou de déception relèvent d’un art, d’un genre, et de leurs conventions. Les Corinne ou les Lesbie auxquelles ils les adressent sont des scriptae puellae, des « demoiselles écrites », dont l’existence, réelle ou non, importe peu au beau jeu du poème.

Pourquoi cette insincérité, ces impostures, ces trompe-l’oeil, ces jeux de masque séducteurs? Il faut s’y faire : pour la joie virtuose de jouer librement de l’ironique puissance d’illusion dont dispose sur ses lecteurs et lectrices le langage poétique, joie d’un tout autre ordre (surtout lorsqu’elle prend pour sujet et pour emblème les blessures d’Eros), que les plaisirs « vécus », sinon partagés, de l’alcôve. Pour l’Ovide des Amours qui a fait croire, au centre de sa fiction amoureuse, à une imaginaire « Corinne », le comble de l’humour est atteint lorsqu’il se surprend, jaloux de son propre succès, à redouter que ses lecteurs ne deviennent réellement amoureux de cette beauté de parchemin !

Sur cet arrière-fond d’élégie grecque et romaine, Mireille Huchon démontre que Louise Labé, la « Sappho françoise », est un « emploi féminin », inventé de toutes pièces par un groupe de poètes réuni autour de Maurice Scève, le Mallarmé lyonnais du XVIe siècle, capable tout comme le Racine de Phèdre ou le Mallarmé d’ Hérodiade de travestir sa voix pour la prêter à une grande cantatrice fictive. La démonstration de Mireille Huchon est irréfutable et réjouissante, même si elle doit faire rentrer sous terre les exégètes et les biographes qui, depuis le XIXe siècle, ont pris au pied de la lettre un double jeu poétique « de haulte gresse » dont le sel attique leur a échappé.

« LOUER LOUISE »

S’il y a querelle entre l’auteur et les derniers croyants de « Louise Labé », elle s’achèvera comme celle qui opposa, dans les années 1960, Frédéric Deloffre à Yves Florenne, celui-ci soutenant, après beaucoup d’autres, dont Stendhal, que les bouleversante s Lettres de la religieuse portugaise (1669) étaient l’oeuvre d’une soeur Mariana Alcoforado, s’adressant à un officier français qui l’aurait séduite et abandonnée, alors que Deloffre prouvait que, Mariana ou non, ces Lettres étaient l’exercice littéraire, imité des Héroïdes d’Ovide, d’un gentilhomme français fort lettré, Guilleragues. De sa vie celui-ci n’avait mis les pieds au Portugal, mais il était des amis intimes de Molière, lequel est l’auteur, comme chacun sait, d’autres plaintes amoureuses sublimes, telles celles d’Elvire dans Dom Juan (1663).

Les poètes qui, avec Scève et son brillant éditeur Jean de Tournes, ont composé les Œuvres de Louise Labé, Lyonnoise (I545), qui ont concouru à célébrer cette Sappho imaginaire dans une « guirlande » qui occupe la moitié du recueil, qui ont fait exécuter la même année, par un excellent graveur, un portrait de la fictive poétesse (non joint à ce livre), n’avaient nullement en tête de gagner une bataille dans la « guerre des sexes ». Au contraire, ces lecteurs de Platon, de Ficin, de Léon Hébreu, ces disciples de la Diotime du Banquet, en prenant les devants, en inventant une « Sappho françoise » et son oeuvre lyrique, entendaient créer un exemple qui encouragerait leurs partenaires féminines à entrer hardiment, comme déjà la soeur de François Ier, Marguerite de Navarre, et comme plusieurs Italiennes, dans la lice poétique et littéraire.

Dès 1542, Clément Marot incitait en vers ses confrères lyonnais à « louer Louise », jeu de syllabes comme les poètes d’alors les adoraient, et qui équivaut au « laudare Laura » de Pétrarque. Cela revenait à leur proposer,pour exercice de leur talent, de créer une autre Laure, rivalisant avec la fascinante « demoiselle de papier » du Canzoniere italien. La Laure poétique de Pétrarque n’avait jamais eu qu’un rapport tout nominal avec Laure de Noves, puis de Sade, pas plus que la « Délie » de Scève (1544) avec une inspiratrice improbable.

Exista-t-il à Lyon une Louise Labé qui n’a pas laissé d’autres traces littéraires que le petit recueil de 1545 et les jeux de mots (Labe-rinte, La-soif de bai-sers) auxquels ce nom se prêtait? Faut-il l’identifier à la courtisane lyonnaise que l’on appelait «la belle Cordière»? Sauf un nom et un surnom, elles sont restées toutes deux de parfaites inconnues. L’une ou l’autre ne furent jamais, au mieux, que des prétextes. Scève et ses amis, Olivier de Magny (auquel on a, au XIXe siècle, prêté, comme à Marot, une ardente liaison avec l’imaginaire Sylphide lyonnaise), Jacques Peletier du Mans, Guillaume des Autels, entre autres, ont donné un tour d’écrou supplémentaire à l’antique puella scripta du désir élégiaque. Non contents de « louer Louise », ils se sont employés à lui prêter le talent dont ils la louaient, réunissant sous son nom une exceptionnelle offrande lyrique.

A la même époque, à Lyon, un descendant de Laure de Sade publiait un recueil de poèmes en réponse au Canzoniere : il les attribuait à ladite Laure. L’éditeur et ami de Scève, Jean de Tournes, attribuait au poète la découverte en 1533 du tombeau de Laure, d’où il aurait tiré un sonnet manuscrit et inédit de Pétrarque. Autant de supercheries qui trompaient sans tromper personne, dans ce milieu de littérature raffinée. Les grands rhétoriqueurs lyonnais de l’amour n’ignoraient rien ni des paradoxes cruels et facétieux dont Eros, « le petit dieu félon » (Montaigne dixit), est fertile, ni surtout des délices et déceptions dont le langage est capable lorsqu’il est chauffé à blanc.

Exit Louise Labé. Mais la mince brochure (un superbe dialogue en prose de Folie et Amour, trois élégies, vingt-trois sonnets déchirants) qui a suffi,avec les éloges d’un choeur de poètes, à faire exister une personnalité poétique hors pair, ne perd rien au change. Au contraire, ce que ce recueil abandonne dans l’ordre romantique de la « sincérité », il le gagne dans l’ordre du sentiment de l’art, de sa puissance à prêter la parole à l’éternelle violence androgyne du désir, mais aussi de l’ironie supérieure avec laquelle il se joue et se moque de sa propre puissance d’illusion et de

déception. Merci, Madame.

Marc Fumaroli

~~~~~~~~~~

Article de Libération

Louise Labé, femme trompeuse

article paru dans l’édition du 16.06.06

La poétesse la plus célèbre du XVIe siècle, figure du féminisme, ne serait qu’invention. C’est la thèse défendue par l’universitaire Mireille Huchon, qui jette un doute sur le travail des biographes.

par Edouard LAUNET

Au 28 de la rue Paufique, à Lyon, est apposée une plaque sur laquelle nous lisons: *«La poétesse Louise Labé "La Belle Cordière" vécut en ces lieux au XVIe siècle.» Cette indication est hélas doublement erronée. D’une part, ladite «maison de Louise Labé» a été rasée au XVIIe siècle. D’autre part, et c’est nettement plus embêtant, la poétesse Louise Labé n’a jamais existé. C’est du moins ce qu’affirme Mireille Huchon, professeure à la Sorbonne, dans un ouvrage, Louise Labé, une créature de papier (éditions Droz), qui fait de jolies vagues. La poétesse la plus élèbre du XVIe siècle ne serait qu’un personnage inventé par un groupe de littérateurs lyonnais. Ceux-ci se seraient amusés à «louer Louise» comme du temps de Pétrarque on s’entraînait à «louer Laure», femme idéalisée. Un exercice de style, une créature de papier, bref une mystification. C’est ainsi que seraient nées les fameuses OEuvres de Louise Labé Lyonnaise, parues en 1555, qui contiennent en particulier vingt-quatre sonnets dont beaucoup connaissent encore aujourd’hui, soit un demi-millénaire plus tard, quelques bribes et notamment celle-ci : «Baise m’encor, rebaise-moi et baise/ Donne m’en un de tes plus savoureux/ Donne m’en un de tes plus amoureux/ Je t’en rendrai quatre plus chauds que braise» * (sonnet XVIII).

Car Louise Labé passait pour une fille très dégourdie. Son oeuvre exprime la passion amoureuse du point de vue féminin une révolution pour l’époque. Et ses OEuvress’ouvrent par un texte une épître dédiée à«Mademoiselle Clémence de Bourges Lyonnaise» qui est l’un des tout premiers plaidoyers aux tonalités féministes. Citons-en l’incipit: «Etant le temps venu, Mademoiselle, que les sévères lois des hommes n’empêchent plus les femmes de n’appliquer aux sciences et disciplines: il me semble que celles qui [en] ont la commodité doivent employer cette honnête liberté que notre sexe a autrefois tant désirée.»=Les femmes doivent avoir une éducation, comme les hommes, et délaisser *«quenouilles et fuseaux»pour se saisir de la plume.

Statue déboulonné Tout cela, plus le fait qu’une biographie très lacunaire prête à Louise d’infinies qualités elle sait le latin, l’italien, l’espagnol, la musique, est excellente cavalière, s’est initiée aux métiers des armes, participe à des tournois… a fait de Louise Labé une figure légendaire du proto-féminisme. Malheur à qui déboulonnera la statue! Or voilà que c’est une femme qui le fait, et qui plus est une femme au sérieux et à ’érudition largement reconnus : Mireille Huchon. Dans son minuscule bureau de la Sorbonne, la directrice de l’UFR de langue française a le sourire de quelqu’un qui vient de jouer un bon tour. Comme si elle-même venait de plier une jolie cocotte de papier. Sauf que l’auteure de Rabelais grammairienn’est pas exactement une farceuse, et que son étude sur Louise Labé n’a rien du roman de gare. En analysant les textes, contexte et paratexte, Mireille Huchon dit avoir repéré un "faisceau n’indices"convergeant vers cette conclusion : ce sont les poètes fréquentant l’atelier de l’imprimeur Jean de Tournes, réunis autour de Maurice Scève et de quelques autres, qui ont créé les oeuvres de Louise Labé, à savoir les vingt-quatre sonnets, le Débat de folie et d’amour en prose et trois élégies. Le Débat devrait beaucoup à Maurice Scève, les poésies à Olivier de Magny, Claude de Taillemont, Jacques Pelletier du Mans et autres gentilshommes.

Cette controverse autour de Louise Labé ne serait sans doute pas sortie du cercle fermé des seiziémistes (quatre cents personnes en comptant large) si l’historien et académicien Marc Fumaroli n’avait procédé dans le Monde (du 12 mai) à une tintamarresque recension de la Créature de papier sous le titre : «Une géniale imposture». «La démonstration de Mireille Huchon est irréfutable et réjouissante, même si elle doit faire rentrer sous terre les exégètes et les biographes», écrit Fumaroli. Et plus loin cet adieu lapidaire : «Exit Louise Labé» Au nombre des personnes censées se retrouver six pieds sous terre, il y a Madeleine Lazard, qui a publié en 2004 une très convaincante biographie de la poétesse (1). Dans son vaste appartement tout entier aux couleurs de la Perse (la spécialité de son mari, l’orientaliste et linguiste Gilbert Lazard), la présidente honoraire de la Société d’étude du XVIe siècle apparaît plus intriguée que catastrophée: «Mireille est une amie, et elle ne m’avait rien dit !» Madeleine Lazard a donc découvert le livre aprèpublication. Elle loue chez sa collègue «une patience de détective et une admirable érudition». Mais elle n’est absolument pas convaincue. «Cette argumentation peut séduire de bons esprits, mais il faut bien avouer que ces indices ne forment qu’un faisceau de présomptions. Celles-ci suffisent-elles à condamner la poétesse Louise Labé ?»

Condamner, le mot est fort. Dans le fond, Madeleine Lazard reproche à sa collègue d’avoir travaillé en pure technicienne sans prendre en compte la qualité des poèmes et leur unité. Cette poésie innovait, au milieu du XVIe siècle, parce qu’elle se libérait des sempiternels thèmes pétrarquistes et platoniciens, ainsi que de la tradition courtoise. Or, «les poètes que Mireille Huchon désigne en auteurs probables n’ont jamais rien fait de comparable»,note Madeleine Lazard. De toute façon, ne dispose-t-on pas de multiples preuves de l’existence de Louise Labé: témoignages, documents notariaux et même testament?

Instrument de mystification

Mireille Huchon ne conteste pas l’existence d’une Louise Labé de chair mais, pour elle, cette personne n’aurait été qu’un instrument (volontaire ou pas, on ne sait) de la mystification. «Pour le lecteur moderne, la chose peut apparaître comme une supercherie littéraire, mais à l’époque tout le monde savait probablement que c’était une fiction.» D’ailleurs, relève Mireille Huchon: «Comment expliquer qu’en 1555 paraisse ce livre fulgurant, accompagné de l’éloge de tous les grands poètes lyonnais, et qu’ensuite on n’en parle plus du tout pendant des années ?»

Madeleine Lazard rétorque que Lyon a connu des années difficiles peu après cette publication, avec la peste et l’invasion des troupes de la Réforme: «Ce ne sont pas des circonstances qui favorisent la poésie amoureuse.» A son tour, la biographe interroge: «Comment expliquez-vous que la seule édition des OEuvres en dehors de Lyon a été faite à Rouen (en 1556), sinon par le fait que l’amant de Louise Labé, le banquier Fortini, avait des affaires là-bas ?»

Interrompons là cette partie de ping-pong pour donner la parole à François Rigolot, professeur de littérature française à l’université américaine de

Princeton. Cet homme, auteur de plusieurs études sur la poétesse lyonnaise (2), défend une position intermédiaire : Louise Labé a bel et bien existé en tant que poétesse, mais *«son oeuvre, comme d’ailleurs beaucoup d’oeuvres avant la promotion du solipsisme romantique, est sans doute le produit d’une entreprise collective». Dans le texte qu’il nous a adressé, titré d’un facétieux «Supercherie ou superbe chérie ?», François Rigolot détaille quelques supposés précédents: «Marguerite de Navarre ne consultait-elle pas son "valet de chambre" un certain Clément Marot sur la facture de ses vers et le tour de ses rimes ? Rabelais n’a-t-il pas écrit son Pantagruel avec le concours actif de ses amis carabins ?» Le prof de Princeton ajoute: «Ronsard lui-même, le grand Ronsard, qui embouchait à tout moment la trompette de la Gloire pour revendiquer la Priorité dans le renouveau des lettres, ne doit-il pas une bonne partie de son oeuvre à ses condisciples de la Pléiade ?»

Cette idée d’oeuvre collective, avec ou sans Louise, laisse Françoise Charpentier très sceptique. Cette spécialiste du XVIe, qui, en 2001, a supervisé l’édition des poésies de Labé chez Gallimard, souligne que les OEuvres de la Lyonnaise forment un ensemble cohérent, avec des particularités de style et de pensée que l’on retrouve d’un texte à l’autre: «J’ai du mal à croire que cela soit le fruit d’un travail à plusieurs mains.» Travail d’ailleurs si cohérent qu’il a fait l’an dernier son entrée au programme de l’agrégation de lettres modernes!

Reste à évaluer ce que l’identité réelle de son auteur ajoute ou retranche à la qualité d’une oeuvre qui vaut en partie par l’affirmation d’un point de vue singulier : celui d’une femme de la Renaissance. «Ça m’est parfaitement égal que ces OEuvres soient ou non de Louise Labé. Si c’est de quelqu’un d’autre, ce quelqu’un a du talent», estime Françoise Charpentier, qui ne peut s’empêcher de penser qu’il s’agit d’une quelqu’une.

Homme, femme, les deux, plusieurs ?

Pour François Rigolot, de Princeton, une production coopérative ajouterait du sel à l’affaire : «Montaigne portait aux nues "l’art de conférer" et c’est bien cet art de la coopération qui rend la production des siècles passés si émouvante et si riche aux yeux des Modernes.» Louise Labé était assez séduisante en première figure du féminisme, mais en créature de papier elle n’est pas mal non plus: la supercherie n’est-elle pas consubstantielle de la fiction? Ne jalonne-t-elle pas toute l’histoire littéraire? Ainsi Clotilde de Surville, poétesse du XVe siècle dont les textes enthousiasmèrent les Romantiques jusqu’à ce qu’on réalise que cette écrivaine, était pure invention. Ainsi Clara Gazul, née de l’imagination de Mérimée. Ainsi, côté hommes, Emile Ajar auquel Romain Gary est allé jusqu’à donner les traits de son neveu Paul Pavlowitch. Et puis encore Jeanne Flore, Louvigné du Dézert, Marc Ronceraille, Colombine de Sennebon, Vernon Sullivan et même les «22 lycéens» auxquels ce journal a cru longtemps, au point de publier leurs lettres, avant que ne se démasque leur véritable auteure, une demoiselle B. de Lyon (3).

Sur Louise Labé, il est probable que nous n’aurons jamais le fin mot de l’histoire. Homme, femme, ou les deux, ou plusieurs? laquo;Au train où vont les choses, Louise Labé risque de passer du statut d’icône des gender studies à celui d’icône des queer studies (4)»sourit Mireille Huchon en nous priant de ne surtout pas la prendre au mot.

Pauvre Louise : «Je vis, je meurs, je me brûle et me noie» (sonnet VIII).

(1) Louise Labé, Fayard.

(2) Notamment Louise Labé ou la Renaissance au fémini, Honoré Champion

Ed.

(3) Pour une liste complète, voir Supercheries Littéraires, de Jean-François Jeandillou, Droz Ed.

(4) Gender et queer studies désignent aux Etats-Unis les études relatives aux implications sociales et culturelles du masculin, du féminin et du transgenre.

— Elinor Dec 15, 6:56am # - I replied to Anna:

Thank you for telling me the rank and position of Huchon. I don’t take rank and position to be a sign of honesty necessarily (most of the time to the contrary) nor competence particularly. It shows Huchon knew and continues to know how to politic, network, maneuver, went to the right schools, had the right connections, was born to the right people.

Marc is a man’s name. As I wrote Marilyn Hacker said the males particularly were having a field day.

If I made a mistake about Labe I apologize, but I do think I said her husband was said to be rope-maker. We are not sure about anything about her. I don’t know if I said this but if not I’ll say it now: I chose to work on Vittoria Colonna and Veronica Gambara over Gaspara Stampa because 1) both being upper class there was a biography and sure documents saved); and 2) I didn’t want to get into the hopeless business of a) having to argue against those who want to deny it lest their subject lose status that Stampa was a prostitute; and 2) for my pains to feel I now have gained sneers at the woman no matter how polite the language of the response might be on the surface. Not only prostitutes of course, but all people under those of high rank left few documents. This was common for most people at the time. There was nothing to be gained and often something to lost to tell about yourself.

As to Labe’s line of work itself, I said she may well have been a prostitute, and so was Stampa and Franco. She may not. There is ample evidence Franco was and enough evidence Stampa was. "Courtisan" is a fancy word for the trade; one which confers status to some people as it suggests they are upper class in their manners and place of business. I agree such a prostitute would probably be somewhat safer than a woman who had to do her business on the streets but not much. Both Stampa and Franco died young, and we have no idea how they were treated by the men around them. Stampa’s

poetry is mythic.

E.

— Elinor Dec 15, 7:55am # - Fran wrote:

"Dear Ellen, Anna and all,

The odd thing about the present Labé controversy is how ready and eager many people are to take as fact what seems to rest largely on theory and conjecture and to be insusceptible of any really concrete proof in itself.

I thought Hacker made a good point when she said that, given the personalities involved, it was highly unlikely that nobody would have patted themselves on the back and gone public with the scam if they really had succeeded in pulling the wool over everyone’s eyes.

If it was supposed to have been such an open joke within the literary coteries in Lyon at the time as has equally been suggested, it also seems odd that writers such as Philibert de Vienne should have bothered to vilify and attack her, as he did in 1547, in fact he was the first one to link her name with the courtisane, ‘La belle Cordière’, from what I recall.

There's an interesting Lyon site giving what is known of Labé's life in French - this is supported in part by documentary evidence such as wills and deeds:

_http://www2.ac-lyon.fr/enseigne/lettres/louise/lyon/biolab.html_ (http://www2.ac-lyon.fr/enseigne/lettres/louise/lyon/biolab.html)

and for the non-French readers a brief Wikipedia account which includes the portrait you mention in your blog and (dissenting) mention of the Huchon controversy:

_http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_Lab%C3%A9_ (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_Labé)

Fran

— Sylvia Dec 15, 7:58am # - Yes, I am struck by no one at the time suggesting the least amusement or hints of this. In the 18th century frauds were exposed just about immediately. The 18th century was a time where this sort of thing was done—though mostly by people attempting to break into the coteries that counted in iconoclastic ways and then by most people who counted at the time regarded as cranks (to use the modern denigrating term).

I am myself at a loss in the sense of having details to cite since (as I just wrote) I didn’t go far into Labe. I saw how little was known and knew that I hadn’t the connections, time, money, personality to go to libraries myself. For Gaspara I was dependent on an Arab scholar who is still (to my mind) one of the central sources of Stampa studies; what happened to Franco was she was accused of being a witch; there was a trial and the evidence from this trial has been in public conversation ever since. My main source for Labe remains the Droz book. I have now though bought the University of Chicago volume and am waiting for it to arrive.

I also like how Marilyn Hacker said she wished a feminist Renaissance scholar of high rank and known knowledge and probity were writing on this. I wish Simone de Beauvoir were still alive.

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 15, 8:00am # - IN a response on Wompo to Marilyn Hacker I added:

Not only prostitutes of course, but all people under those of high rank left few documents. This was common for most people at the time. There was nothing to be gained and often much to lose to tell about yourself, especially if you were a woman. I remember in my small paper on Anne Cecil de Vere (Countess of Oxford, and wife to the wretch Oxfordians want to attribute Shakespeare’s work to) I ended on the reality (as I see it) that it was in no one’s interest at the time to tell of her life story or attribute the 6 poems I attributed to her once again. That’s another controversy about attribution.

If anyone’s interested, here’s a summary by me in 6 paragraphs prefacing my original paper (now on line):

http://www.jimandellen.org/anne.cecil.poems.html

Attribution studies before the later 18th century are just a mess of attribution & counterattribution. There are about 6 poems either by Colonna and Gambara which have moved back and forth in their respective columns. Myself I disagree with A. Bullock, the editor of the 1982 edition of Colonna and would give the poems he gives to Colonna back to Gambara (and one woman Neapolitan scholar who has read the manuscripts has now written a couple of articles attacking Bullock’s "magisterial" intimidating volume). It was beneath the dignity and thought to detract from respect for people who wrote at the time to put their name to their work. Much was circulated in manuscript. The book here is Margaret Ezell’s. I claim a whole bunch of poems for Anne Finch (Countess of Winchilsea, 1660-1720, not Annie) which are still not put in her column surely.

Another problem (sorry for the scattiness of this but I have 66 sets of 5 papers (portfolios) to read and grade by Sunday and feel pressured to hurry) is not just nonsense stories (women didn’t fight on horseback), but also overclaiming things for women. Retha Warnke talked of this. In her excellent book on Renaissance and Reformation women Warnke did all she could to argue very few women could read Latin, and do all the sorts of stupendous feats attributed to the few who were learned. (But has generally been ignored; people prefer to repeat myth and not see how little each of us can ever know.) This is to do women a disservice. The Victorian novelist who I wrote a book about, Anthony Trollope, actually said more than once women should be overpraised and he meant that to do this would be semi-dismissive of them, treat them as women you are being overcourteous too, not professionals or your competition; he was an editor of an influential quarterly at the time.

Not only those who read can see you are making a fetish and cult (ultimately of yourself for studying this person), but then when someone want to argue against whatever you wrote they have the immediate easy target of the pragmatic error or absurdity. This may been seen in some of what is said below about what was claimed for Labe. For my part the only reason I say in my biography that Gambara could read Latin is she wrote a poem in Latin (and I don’t think someone else wrote it for her); I doubt Colonna was competent in Latin because she left nothing in Latin and if you read her letters you find her Italian mixed with Spanish of the time (her husband’s background was Spanish and her father spent much time in Naples and so did she) and dialect and yet it’s easy to find scores of essays attributing miracles of learning to her.

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 15, 8:13am # - From Wompo:

"I don’t know much about the 15th century but I’ve heard an awful lot of people, including literature scholars, express disbelief that women could have had educations or could have been writing in the 1600s. And I’ve seen enormous anthologies of poetry written by women in Europe in the 1600s, and I figure whatever got into anthologies was just the tip of the iceberg.

I also know about Wallada (5th cent. Spain), Maria Alphaizuli "The Arab Sappho" (Seville, 8th century), Maria Abi Jacobi Alfarsuli (Seville, 11th century), Aisha of Cordoba (12th), Labana (10th) also from Cordoba; they were poets and translators.

I would doubt that they were lone and lonely examples, even if they’re all I happen to know. When I investigate women writers from more recent times, I tend to find that they knew other women writers, that they were not lone exceptions in a world of writing men, even if they came out of a few hundred years of history on top; As in many movies and narratives, "there can be only one" so that even in situations where there were women’s newspapers, journals, circles of letter-writers and poetry-transcribers, all that lively exchange is erased so that it looks as if there is a single freakish woman who somehow managed to exist or compete with men in a poetry scene run by men.

Just a couple of years ago in Japan, a literary magazine claimed that Mari Kotani had not written her award-winning science fiction novel – her husband must have written it. She sued them and won, and began The Association for Defending Female Authorship. (http://enjoy.pial.jp/~fdi/FDI.html).

I would also suggest people read "How to Suppress Women’s Writing" if they haven’t already—an excellent, short, outline by Joanna Russ on the rhetorical tactics used to deny women’s agency.

Please remain very skeptical of the erasure of Louise Labe. As we see, all it takes is a suggestion and people are willing to shrug and accept the unlikeliness of women writers.

Ignorance, and a failure of imagination, are at fault as much as sexism.

200 or 500 years from now I will seem unlikely. I suspect we all will.

In fact, we are unlikely; we are very privileged and our education level is rare for people on this planet but especially for women. Even now. It will be easy to disbelieve in us. We’re just a few aristocrats who can and probably will be discounted by future history. We should not fool ourselves that things have changed significantly or permanently for the better as far as women’s rights and power are concerned.

Liz H"

— Elinor Dec 15, 11:21pm # - I’d like to feature this in the next (tomorrow’s!) blog Carnival of Feminists. See http://feministcarnival.blogspot.com/

— Sandy D. Dec 19, 2:40pm # - Annie Finch contributed her own translations of the two poems I cited from the Edinburgh Bilingual Library and Droz:

"Thanks everyone for the encouraging and thoughtful responses to the Labe thread. I am sharing them with my co-translator who did the prose and the background notes, Deborah Lesko Baker, who being a longtime Labe scholar, is up to her ears nowadays in responding to this controversy. . .

As solstice gift from Louise, whoever she may have been, and me, here are my versions of the two sonnets Ellen posted the other day.

Annie

SONNET 18

Kiss me again, rekiss me, and then kiss

me again, with your richest, most succulent

kiss; then adore me with another kiss, meant

to steam out fourfold the very hottest hiss

from my love-hot coals. Do I hear you moaning? This

is my plan to soothe you: ten more kisses, sent

just for your pleasure. Then, both sweetly bent

on love, we’ll enter joy through doubleness,

and we’ll each have two loving lives to tend:

one in our single self, one in our friend.

I’ll tell you something honest now, my Love:

it’s very bad for me to live apart.

There’s no way I can have a happy heart

without some place outside myself to move.

SONNET 19

Diana, standing in the clearing of a wood

after she had hunted her prey and shot it down,

breathed deep. Her nymphs had woven her a green crown.

I walked, as I often do, in a distracted mood,

not thinking—when I heard a voice, subdued

and quiet, call, “astonished nymph, don’t frown;

have your lost your way to Diana’s sacred ground?”

Since I had no quiver, no arrows, it pursued,

“dear friend, who were you meeting with today?

Who has taken your bow and arrows away?”

I said, “I found an enemy on the path,

and hurled my arrows at him, but in vain—

and then my bow— but he picked them up in wrath,

and my arrows shot back a hundred kinds of pain.”

— Elinor Dec 19, 5:06pm # - Artemis (Diana), as an archetype, stories told about her, and various suggestive motifs connected to her (sometimes at quite a distance) were enormously popular in Renaissance poetry. The archetype and her visibilia often make for powerful poems, especially when the woodland imagery is connected (Freudian-like intertextuality here) to Aphrodite (Venus). For example, the male perspective from Edmund Spenser’s Amoretti:

Lyke as a huntsman after weary chace,

Seeing the game from him escapt away,

sits down to rest him in some shady place,

with panting hounds beguiled of their prey:

So after long pursuit and vaine assay,

when I all weary had the chace forsooke,

the gentle deare returnd the selfe-same way,

thinking to quench her thirst at the next brooke.

There she beholding me with mylder looke,

sought not to flye, but fearlesse still did bide:

till I in hand her yet halfe trembling tooke,

and with her owne goodwill hir frymely tyde.

Strange thing me seemed to see a beast so wyld,

so goodly wonne with her owne will beguyled

The female from Mary Wroth, Pamphilia to Amphilanthus

Late in the Forest I did Cupid see

Cold, wet, and crying he had lost his way,

And being blind was farther like to stray:

Which sight a kind compassion bred in me,

I kindly took, and dried him, while that he

Poor child complain’d hee starved was with stay.

And pined for want of his accustom’d prey,

For none in that wild place his host would be,

I glad was of his finding, thinking sure

This service should my freedom still procure,

And in my arms I took him then unharmd,

Carrying him safe unto a Myrtle bower

But in the way he made me feel his power,

Burning my heart who had him so kindly warmed.

A variation, Aphra Behn, subject to Eros (Cupid), song from Abdelazar:

Love in fantastic triumph sat

Whilst bleeding hearts around him flowed,

For whom fresh pains he did create,

And strange tyrannic power he showed,

From thy bright eyes he took his fire,

Which round about, in sport he hurled;

But ‘twas from mine, he took desire,

Enough to undo the amorous world.

From me he took his sighs and tears,

From thee his pride and crulty;

From me his languishments and fears,

And every killing dart from thee;

Thus thou and I, the god have armed,

And set him up a deity;

Bu my poor heart alone is harmed,

Whilst thine the victor is, and free.

When you compare the boldness of Labe’s approach, the absence of triumphing over one another and sadomasochism, you can see why she became a feminist icon.

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 19, 5:12pm # - Annie Finch:

"A few years ago I visited the Chateau d’Anet, built by the design of Diana of Poitiers, Mistress of Henry II. The motif of Diana the Huntress is everywhere throughout the house. A bit strange because she was a virgin goddess, but that may have added to the feminist frisson of the whole Diana imagery. Scroll down at this link to see a statue of Diana of Poitiers with stag

http://pascale.olivaux.free.fr/Histoire/Pages/Anet.htm

Annie"

— Elinor Dec 19, 5:19pm # - To add a modern use of the imagery: in the recent film, The Queen, as Queen Elizabeth II (Helen Mirren) tramps across the vast gorgeous Scots landscape of Balmoral, she comes upon a stag and feels great pity for him as she knows he is hunted by her husband and grandsons. She urges him, "shoo shoo," and is much relieved when he vanishes. It’s clear she identifies at that moment.

Later the stag is killed in a stupid way (with much more pain than was necessary) by an American businessman tourist (anti-American vibes here) and she visits the corpse hanging upside down. Then it’s identified by her not only with herself, but also Diana Spencer who the film frames as partly having paid the price for her attraction to herself and use of intense publicity.

Diana Spenser, a Venus to some.

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 19, 5:20pm # - Just a by-the-way, thinking about Aphra Behn, I’d like to say how very little is known for sure about Aphra Behn, and much of what passes for biography is hear-say and worse.

Not too long ago Germaine Greer published a couple of articles where she attempted to demolish the conventional story of Behn’s life (as told by Duffy, Goreau and even Todd) and substitute one (I think) more likely but which produces a very different woman. It aligns with a life written by Sara Mendelson (in a book called The Mental World of Stuart Women). Among other things Greer argues that Behn was not able to support herself by her pen, but rather her writing supplemented what she got through living with men; Greer argues for a slightly different canon (she presents the plays attributed to Killigrew said to be those Behn adapted for hers, as at least written out if not revised by Behn herself). I find Greer convincing.

Last night I went to hear a very good dramatic-reading of Edward Bond’s Bingo: Scenes about Death and Money and met an Oxfordian. He went on about how Shaks-pear wrote none of these plays and how deluded we all were. The funny thing is he was able to muster all the problems in the biography. Not to say that there is an attribution controversy here: we have the folio by Hemmings and Condell and the publications of Shakespeare’s separate plays as well as his sonnets during his lifetime. But of Shakespeare’s life we really know very little.

Now since biography is so central to the way people perceive and frame texts (what the average person seems to care about most is identity—another play in the series I went to was by Alan Bennet, Kafka’s Dick, a brilliantly hilarious and witty-take off on the reality that what has made Kafka known and led to how he is read is Max Brod’s biography), the lack of one and parlous nature of attribution before the later 18th century makes all but the most powerfully-connected women anyone’s target.

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 19, 9:39pm #

commenting closed for this article