Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_The Lives of Others_: a significant flawed melodrama · 12 March 07

Dear Harriet,

Yesterday I went to see The Lives of Others, written & directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck (made by a German company). You may know it won an Oscar for the best foreign film and 10 nominations in other categories, and has apparently been nominated for the most German film awards ever. Although it’s a flawed film, it’s effective and probably important, I strongly recommend seeing it. The film connects to John Barrell’s book about what happened in the 1790s in England (where for example a man could be hauled into court for something he said which was deemed subversive), The Spirit of Despotism (reviewed by Barbara Taylor for the London Review of Books, 29:3, 1/3/07). Donnersmarck has made an allegory about the open subversion of law in the GDR; this mirrors what the US government under Bush and other countries in the last couple of decades have attempted to begin.

The serious flaw I’ll put first: at the opening and throughout the film it’s suggested that torture really produces the truth; that you can get people to divulge what you know is the truth by torturing them. This is the rationale for torture and is false. People simply say anything you want, and the reason they are tortured is often crazed cruelty or someone is following orders who is willing to be horrifically cruel. The desperation is a false rationale in the way of say Bush’s rationales when he justified his desire to smash Iran: they are speciously true on the surface (Bush’s unacknowledged subtext is this: these non-Christian people hate us so we must destroy their power).

From Beccaria and Manzoni on it has been demonstrated, & through hard evidence (records of cases) that torture is useless in gaining information and is done out of human cruelty and indifference to one another. To present torture in the way it’s presented in this film is to shore up systemic torture going on right now.

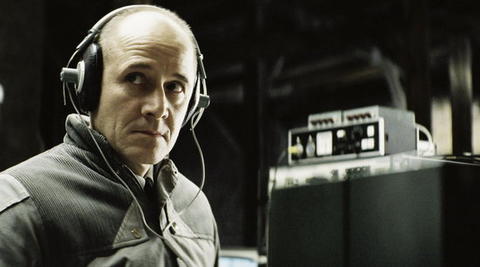

The situation as the film begins: we are in East Germany and watching a teacher Hauptmann Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Muhe) in a school for teaching interrogation. The techniques advocated are forms of torture, intimidation, high humiliating cruelty. The scene switches to a theatre where we are watching a play which clearly embodies social realist ideals: it’s about women in a factory and the lead character is an ideally courageous heroine played by an up and coming beautiful actress, Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck). The playwright, Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch, very handsome, he looks the enlightened type) has a party afterwards, where he’s surrounded by artist friends (other writers are in prominence) and we begin to see he’s been spied on by frightening men belonging to the Stasi (a murderous spy group who represent "state security") who use torture, intimidation, utterly unjustified imprisonment, constant surveillance and career and home-destruction to control any dissidence from the social order they are on top of and made rich and powerful by.

One of these people is also the teacher at the school we began with, Wiesler now revealed as an up-and-coming ruthless spy (Muhe).

Wiesler (Muhe) as nightmarish masterspy

Dreyman approaches the big boss and most powerful of the men Gregor Hessenstein (Herbert Knaup, made to look very fat, dense, ugly-pushy philistine) to try to persuade him to rehabilitate a friend, a director, Albert Jerska (Volkmar Kleinert) on the grounds he is a great director and Dreyman’s play would have been much more effective with an original modernist director and also on the grounds of justice and fairness. Jerska has been wrongly tarred, maligned, is miserable. Hessenstein snorts and in effect turns away.

Hessenstein (Herbert Knaup), characteristic pose, from the side, suspicious

It seems Dreyman can ask such a question because he’s always played the game, remained within the allowed opinions of the party, but this act is going to endanger him. Hessenstein suggests to a man at the head of the Stasi, Oberstleutnant Anton Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur) that he bug Dreyman’s apartment thoroughly; it soon emerges that Hessenstein has been coercing Christa-Maria Sieland into allowing to fuck her; this actress in the play is actually living with Dreyman; Hessenstein wants to eliminate Dreyman as his main rival for this woman’s body.

There is much suspense and drama because we then watch Wiesler, a minor harsh bully at the head of a police bullies bug the house forcefully, and spend day and night watching Dreyman in his apartment. For example, we see Wiesler frighten the woman next door into not telling Dreyman by telling her if she tells what she saw her daughter will be thrown out of her university.

Then the story "proper" begins. Wiesler and his helpers watch each act of Dreyman, take down every word. This watching includes him having sexual intercourse with Christa-Maria. It is horrible to see someone’s life watched step-by-step this way. We look at them through a TV screen with Wiesler:

Sieland (Gedeck) and Dreyman (Koch), view from TV screen

Of course incriminating evidence of some kind (an anti-government statement) will be found eventually. We see Grubitz bully a young man at a restaurant where state functionaries eat together; Grubitz’s behavior and words reminded me of Alistair Sim playing Scrooge (in the 1951 Christmas Carol): mean teasing, cruel triumph, leering power were enacted. Grubitz doesn’t come across as self-evidently evil as Hessenstein, but we see he is capable of just as much cruelty, and is more dangerous in that he is not as obvious. We then see Hessenstein, the Big Man, force the actress, Christa-Maria, into his car and force his hand on her breast, fuck her, and drop her off near Dreyman’s house, and the Big Man bully Grubitz (threatening him with loss of his big-paying prestigious position). Grubitz then pressures Wiesler.

Wiesler begins to play God. He uses his equipment to push Dreyman into going downstairs one morning and Dreyman glimpses Sieland coming out of the big man’s car—half undressed. Now Dreyman knows she is having an affair, and the first night she produces the usual excuse for going out, he begs her not to go, and we and she realize Dreyman knows. She means to go to Hessenstein anyway, but first goes to a bar to have a drink (presumably to steel herself), and Wiesler comes in and orders a drink. He presumably knows this is a bar she goes to regularly by listening in on everything said in Dreyman’s flat.

Then Wiesler comes over to Christa-Maria’s table, and we see he is a "fan" type and worships her from afar. He persuades her not to go to the Big Man, but return home. We think he is doing all he can to make the situation worse so as to push Dreyman into doing something the police can use against him. But eventually we discover there was another motive, for strangely when Dreyman does begin to do something utterly forbidden, Wiesler pretends not to understand what he sees and hears through his TV and sound equipment and protects Dreyman.

Dreyman’s director friend, Jerska, commits suicide. He had written a book (music? play? we are not sure) called Sonata for a Good Man which he sent Dreyman just before he killed himself. Dreyman is so angry and distressed, he writes an essay on the real condition of private life in the GDR and with three other friends manages to smuggle it into West Germany (the FDR). All this is done in the apartment, including a typewriter brought in whose typeface will not be traceable. The deluded Dreyman thinks his apartment is not bugged because he has been so obedient to the state functionaries. Christa-Maria does tell Dreyman not to tell her anything more than she sees as she doesn’t want to know anything that can be dragged out of her. It seems she is on medication of some kind which is forbidden by the state, and this endangers her—as well as her having broken off her affair with Hessenstein who is all the while pressuring Grubitz. Grubitz begins to suspect something is wrong with Wiesler as Wiesler has not yet produced any incriminating evidence.

We see this too, but what his motives can be we don’t know. Instead of describing the essay as it’s discussed in the apartment, Wiesler calls it a play. An underfunctionary suggests to Wiesler it’s not a play, but Wiesler scorns and bullies him as someone beneath him, and the underfunctionary says no more about the distorted presentation of this essay as a play in the records.

Dreyman’s article is published in West Germany and Hessenstein, Grubitz and their upper level colleagues are incensed. Grubitz has a typewriter expert in to try to find which typewriter did it, but is told (after a long disquistion on types of type) that this one is not traceable.

Finally, Grubitz thinks to pick up Christa-Maria while at the doctor and threaten her. He has the power to end her stage career. He does know she is on "drugs" from Wiesler. When she offers sex, and he says she has an "enemy" so this will not do, she quickly cracks. Dreyman’s apartment is brutally searched in front of him, but the typewriter has been put below the floor and is not found. Later on as viewer we realize Wiesler would have known of this and yet did not tell.

Already suspicious of Wiesler, Grubitz drags him in to be interrogated and threaten him, and then to interrogate Sieland and threaten her. She is treated courteously throughout: her punishment thus far is isolation in an iron room cage in a prison. She again cracks and tells where the typewriter is. She is allowed to return to Dreyman, given a name as "an informant" and told to lie to Dreyman.

Grubitz (Tukur) watching Sieland (Gedeck) through mirror

Now we switch to the apartment and see Christa-Maria arrive, refuse to explain to Dreyman where’s she’s been. His friends have told him she was nabbed and told the Stasi that he wrote the essay, but he has refused to believe this. He just looks worried about her, but also puzzled. Grubitz and his men break in again. But by the door is Wiesler who unknown is watching them; they do not see them and he slinks away. They search the apartment, and go for the typewriter in the hole beneath the floor, and voila it’s not there.

Meanwhile Christa-Maria not able to take the denouement she expects, rushes out into the street and hurls herself before a truck and is killed. A strongly emotional performance by Kock (Dreyman) proceeds. He grieves over her body intensely. Wiesler watches from afar, silent.

Next scene Grubitz tells Wiesler his career is over. How Wiesler did it, he doesn’t know, but Wiesler somehow protected Dreyman. We guess Wiesler removed the typewriter, not Dreyman.

Fast forward two years and we watch Wiesler (Mühe) in a low paid (humiliating conditions) job steaming open envelopes. He is working for the post office. Suddenly a phone rings: the wall has fallen. Much rejoicing.

Fast forward 4 years and we are in the theatre watching Dreyman’s play, this time done with modernistic symbolic techniques. Dreyman is sitting next to a beautiful woman who is more heavily made up, more sexily dressed than Christa-Maria. She is Dreyman’s latest mistress. He rushes out and encounters Hessenstein in a back room. Hessenstein says, "Ah! you couldn’t stand to watch either." Dreyman wants to know why his apartment was not bugged. (He is improbably stupid and naive over this.) Hessenstein tells him his apartment was bugged. He then tells the truth about the incident of the essay as far as he knows it. Dreyman is overwhelmed with disgust.

Fast forward a few months and Dreyman goes to a building filled with massive numbers of thick files. This is where the Stasi kept its gathered information. He sits at a desk and soon someone wheels out to him a huge stack of notebooks. He begins to read and quickly gets to the notebook which is a record of the incident of writing the essay and Christa-Maria’s death. We look over his shoulder as he reads and together with him come upon the passages where Wiesler wrote lies. Wiesler presented the writing of the essay as the writing of a correct play about Lenin. Dreyman sees Wiesler’s serial numbers. Dreyman has no problem when he asks a clerk who was the man with this serial number.

A few days later we watch Dreyman trailing after Wiesler as Wiesler makes his daily rounds as a humble postman.

Fast forward again. Wiesler, still dressed as a poor man (everyone else looks spruced up), passes by a bookstore and sees advertised Sonata for a Good Man written by Dreyman. A large photo of Dreyman looking very prosperous is in the window. Wiesler goes in and finds an inscription or dedication to his serial number on the first page, "with gratitude." The closing dialogue is the clerk asking if he needs change, and Wiesler saying no, this one is for me. He looks deeply happy.

So the successful playwright has succeeded in sending a secret message to the humble good man.

Some of the other flaws (beyond the one I mentioned at the outset) are self-evident. First, the semi-happy ending. David Lean said don’t pay attention to endings in films (or even books); it’s the middles that count, the endings are sop to selling widely. But in this film the man who is presented as the steely teacher of torture (Wiesler), the ruthless spy on our smallest actions, is shown by the end to have if not a heart of gold, an ability to enter into the playwright’s desires, and himself a pity desire for the actress based on his soppy adoration of her. He meant to save her. Then the playwright (Dreyman) writes a book which is presented as a message of consolation to the steely man who ruined his life on behalf of the playwright who by Wiesler’s actions was never even imprisoned.

This is unreal sentimentality and in implication analogous to the use of central powerful white men as the saviors of the world we see in Amazing Grace. Here the savior is a single ordinary German man.

If this film is presented as a parable of experience, it’s untrue to life. Life moves eventlessly and doesn’t pattern in this way (even if people imagine it so). The finale is improbable, as is the way Wiesler succeeds in playing a finally mysterious and benevolent God. (God works in mysterious ways?) Underlying the film is a James Bond perception of human relationships. I realize this is common to spy and detective fiction, like Le Carre’s for example, but it’s a real weakness. When you read or go to see genre fiction, you can accept this (The Constant Gardener is framed as spy thriller which has an unusually serious message about the drugs companies and larger politics), but this film is touted as a realistic critique and has been given awards which reinforce this idea.

At one point watching such a film I would’ve thought it’s melodramatic hysteria and evil bad guys were a way of condemning all socialism from the point of view of capitalist states, but now minus the melodrama and "evil" trappings, I see it as just as much what is apparently happening in the US (per the patriot act) openly outside its borders and what could happen and perhaps does secretly from within. So it’s a parable about all such state apparatuses. If it’s meant to scare the audience, it does.

Still, as someone who knows very little of East Germany, I wonder how true this portrait is of the difference between the cruel state apparatus before the wall fell and the apparent opening of the state after. Was the paranoid state so much an octopus it could reach into the tiniest crevices of people’s lives? One "lesson" a viewer could come away with is you better not do the slightest good deed or say the slightest word against what’s happening (e.g., writing a blog like this say) because you will be spied upon, and if you keep it up, fired or a member of your family fired. This is the way it’s presented here. Barrell in his A Spirit of Despotism argued the Tory government attempted this sort of thing in the 1790s in England.

Is the present German state without such an apparatus? A fully open society? The playwright is able to get out his files and read everything and discover the minor functionary who observed him. Could one?

It’s a powerful film, effectively acted and filmed, and I nearly burst into tears when Christa-Maria commits suicide and Dreyman moans and groans and writhes over her broken body. I can believe a director was blacklisted and committed suicide (this happened in the US too and for all I know continues to happen in a lesser way still). I liked the making visible how a private revenge and sex motive lies behind use of accusations of dissidence. This is what I’ve been told happened in US communities in the 1950s (you could get someone else’s job by accusing them of communism) and France just after WW2 too. And I suppose everywhere such paranoid-based apparatuses are set up.

There is a sharp irony about the position of women in the film. They are dispensable and interchangeable. They are also flotsam and jetsam upon the sea of life and not to be trusted. This reminds me of the 18th Scots philosopher Millar’s theory about women in the state: he said when women’s bodies are made readily available by society, their power goes down; the only times they are unavailable is when men control them and prevent other men from getting them without their having to pay big prices. So an actress is someone who would be easily prostituted; so too women at work would be readily available. If this is true, it might explain why in the last 30 years women have lost such ground. They go to work, are readily available through office politics. The sexual revolution which allows them to have sex outside marriage is just another step putting men in charge of them as now they have no handle to demand marriage. And indeed in the US working class women do much worse in life than ever. Girls are expected to "put out," have sex with men pretty quickly and nothing given in return but affection or physical pleasure.

At the close of the film Christa-Maria has been replaced by another sexy woman so the playwright was by no means desolated for life. The part she did in the play is now done by a black (African) woman who does it more starkly and effectively and ironically as a male director has made the play so much better.

This is an effective ironic moment in the film yet the melodrama swirling around it makes it feel lurid. What ruined the film was partly what has made it popular: it’s melodramatic. The use of fast-forward in time also revealed a crude sort of parable had been determined upon. In order to provide this pattern the director was forced to pick moments ahead in time to make us see this compensating reaching out between two people, the obscure man and the elite artist.

Last year I saw Sophie Scholl, another German film about the past. At the time I didn’t mention what bothered me about that one. As our students are imprisoned, beaten, and then unceremoniously executed, we see around them many Germany functionaries who look regretful, their eyes filled with pity. How they longed to help these students. In this latest German film the German public is flattered even as their history is presented melodramatically.

For myself I did remember times in my life when I’ve been unfairly treated and could do nothing about it. There’s been a recent incident too; in my case my file was discarded. Different strokes for & by different folks? I remembered how when I was once accused of antisemitism by a student, I was exonerated based on the knowledge a colleague had that some of my relatives were murdered in German concentration camps and also shot dead at point-blank range by Russian officers. It bothered me very much that this history was used to exonerate me from a baseless charge.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Fran, on WWTTA:

"First. the title, Das Leben [the life] deranderen of [the] others. German grammar thinks French not English here.

As for what you said about the practical aspects of the film, I’m probably not the best person to ask here, only having experienced the GDR personally when it was already moribund just before its Fall in 1989, but I can pass on some of the facts I do know and have had confirmed by East German friends when talking about this and similar films. East Germany had a opulation of 17-18 million; the Stasi is known to have kept surveillance files of varying thickness on a staggering 6 million of them. Stasi agents were found busily feeding as many of these as they could to the shredder when the ministry archives were stormed, but about 180 kilometres of files were still secured.

I know comparisons are odious and statistics to be taken with more than a pinch of salt, but figures published recently state that Hitler had about one Gestapo agent for every 2000 citizens; Stalin one KGB agent for every 5830 citizens and East Germany one Stasi official for every 63. If you count the estimated 3 hundredt housand IMS, the Stasi abbreviation for incognito ‘inofficial collaborators’ on many of the secured files, the extent of blanket surveillance in the GDR is even more staggering.

Interestingly enough, one of the things you could imagine happening; that a high party official should abuse the system for his own obviously baser, personal sexual needs,—is one of the things my East German sources said couldn’t have happened in this way. They also said, however, that there is also no way that an important interrogator would have been conducting personal surveillance in the same house as his victims.

More later, my next class calls…...

Fran"

— Elinor Mar 12, 8:05pm # - From Nick:

"Thanks to Ellen for a fascinating review.

As I haven’t seen the film I can’t really comment on the detail but there is something I wanted to pick up on.

This is Lean’s assertion… "David Lean said don’t pay attention to endings in films (or even books); it’s the middles that count, the endings are sop to selling widely."

I am very dubious about this; indeed I think that sometimes the opposite is true, and you have to pay most attention to what actually happens to the characters in the film/book, because that can represent the director/author's intended moral (what I seem to recall from my ancient and rudimentary film studies days is called the Project). I accept there are cases where this is not so and a 'happy ending' is tacked on which is entirely out of keeping with the rest of the film (a case in point is the recent film Dreamgirls).

But Lean's own work provides us with a wonderful example about which to argue the point (maybe he was even thinking of this?): Brief Encounter To me the ending, the re-establishment of familial, Establishment values is absolutely critical. We may remember the scenes between Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard, it may be their station romance which is memorable, but the eventual outcome cannot be cancelled out because of this. It colours our entire view of the film, and what the film is saying. The end in fact overwhelms the middle. Or is intended to. If it doesn't it is because the film allows enough latitude for the viewer to impose their own morality and 'ending'.

This is probably utterly irrelevant but I wanted to try and add something, however incoherent, to Ellen's great review.

Nick."

— Elinor Mar 12, 8:10pm # - Thank you both very much for the comments. Could it be that the kind of state apparatus Hitler started was carried on in Eastern Germany and not Western because the same kind of paranoia developed? This paranoia is what we find in the Bush clique in the US—also used to justify throwing out law and turning to ruthless abuse as tactics for controlling people.

On the improbability of the sex, I’ve often been told that communists were very puritanical. Many of those who rose to mid-level positions actually had come from peasant families originally with a strong work ethic, anti-pleasure, and distrust of sex.

Yes it makes sense the interrogator would keep himself apart from his victims as much as he could. Doubtless that’s done today too. The victim does in fact seethe with frustrated rage and hates him or herself because he (or she) is so helpless and must kowtow to the cruel despot.

I’ve seen Brief Encounter at least twice and think it as important a film as Casablanca: both coming out of the same era in WW2. BE reasserts the important of social continuity above all, safety, the state, the individual in a culture, and promises made to someone who did not break his side of the original bargain (we are not told anyone to make us think Celia’s husband is not a good man); C is deeply sceptical, not to say nihilistic. Let’s round up the usual suspects. Heroism is again self-sacrifice, but not within and for the established order. Film studies about British film made _Brief Encounter (like Now Voyager in both the UK and US, but more the US) an important film.

Ellen

— Elinor Mar 12, 11:08pm # - From Fran:

"Again you ask some very pertinent questions, Ellen, that I’m not sure I can answer, but will give them a crack.

The thing with Eastern Germany is that you didn’t just have the Stasi, you also had the Russians and the KGB breathing down people’s necks, and both the Stasi and the KGB infiltrated Western Germany. It was particularly bad when Stalin was still alive, and still subject to extreme and entirely arbitrary swings of repression and a little more liberality when he wasn’t.

It’s pretty easy to inflitrate when there is no language barrier and people are of common origin. The most infamous and explosive example is the Guillaume affair which lead to Chancellor Willy Brandt’s resignation in 1974. Guillaume, one of the Chancellor’s closest advisors, turned out to have been a Stasi plant right from the beginning. President Putin, for example, earned his spurs as a leading KGB agent in Germany, before becoming overall head of the KGB in Russia and then going on to be political premier. He still speaks perfect German.

From what I gather, Stasi methods in general were not as bloody as the Gestapo’s or Stalin’s, if perniciously destructive: they relied far less on torture or assassination than on this blanket surveillance and the accompanying climate of fear and control, suspected dissidents often being blacklisted and thus prevented from attending school and university or pursuing their chosen careers or alternatively imprisoned and then often robbed of their children in forced adoptions etc. There was also quite a lucrative trade in the sale of dissidents to Western Germany: the government here would pay for their release and expatriation. Others were expatriated against their volition . Protest singer, Wolf Biermann, for example, who lost his GDR passport and was deported to the BRD. Christa Wolf was one of the East German VIPs who signed an open letter protesting their government’s action. Interestingly enough, the Stasi propagated the myth she’d later detracted her signature in order to discredit her in the west. They were successful.

One of the things the woman now in charge of the Federal Institution that maintains and supervises access to the Stasi archives, Marianne Birthler, is presently campaigning for is an investigative paper on the extent of the involvement of present members of the German Federal Parliament in Stasi surveillance both as victims and informers on both sides of the old Wall. Not entirely surprisingly, she’s been refused so far.

As for access in general, as far as I know, everybody has the right to see his or her own files, should they exist; things get more difficult when people demand to see the files on other people, especially politicians. Former Chancellor Helmut Kohl, for example, went to court to prevent journalists from having access to parts of his files and won. Christa Wolf was attacked for the brief period she was listed as an IM as a young and fervent communist and went into the offensive by allowing public access and publication of all of the information in her files – people were unsurprisingly more interested in the thin file as an IM than in the over 40 thick files on her as a surveillance victim herself.

According to the numbers published on the official website,

http://tinyurl.com/yno94r (http://tinyurl.com/yno94r)

There have been 6,022,774 applications to review files since the first were opened in 1991. It doesn’t actually say how many of these were refused, if at all.

Fran"

— Elinor Mar 14, 7:11am # - From Fran:

"To get back to the film itself, I thought you might have strong reservations when it came to the portrayal of the only prominent female role in the cast. I certainly did myself, even if Martina Gedeck played her clichéd victim-role well. It’s an odd thing about East German society: if you think of their politicians only macho-seeming males come to mind, yet the East German women I’ve come to know have usually been far more emancipated in thought & qualified in more untypically ‘female’ professions than many of their Western German counterparts.

As for the Hollywood type ending, there was a bit of a black joke before, the interrogator ended up licking stamps in the cellar next to the lad who had unwisely told the political joke about President Honecker in the canteen at the beginning of the film. What goes around comes around and all that.

Again, East German friends say it would never have happened, but then you can’t really expect absolute fidelity from an aristocratic young director educated in the west. His full name is Florian Maria Georg Christian Graf Henckel von Donnersmarck, Graf meaning Count.

Fran"

— Elinor Mar 14, 7:18am # - All Fran’s information about East Germany and the spy system vindicates the film. In the opening segment when the teacher (Wiesler) is teaching the students how to interrogate, we listen to a tape and watch a film. The man interrogated is not physically tortured. He is humiliated by all the procedures (intendedly so), including self-abasement, demands for docility, you must sit on your hands, and so on. The threats consist of procedures by which his children will be taken from him and either he or his wife exported after spending long periods in prison. When Wiesler and his gang’s bugging Dreyman’s apartment is seen by a neighbour, the threat is if she tells her daughter will lose her place at college (and thus never get a good job) and her husband will be fired.

These kinds of actions are enough to destroy people’s lives. In fact the real answer to why there has been no socialist movement in the US since the end of the 19th century is the government has colluded intensely and continually with business to do just this sort of thing about jobs and places in good schools to leftists and has hounded them to prison too. When a person is thrown in prison, what happens to their children is they are adopted by other family members or go to orphanages. Sometimes the pressure has been explicit and open (in the 1950s), but recently when the crazy rightist types who blew up a federal building in Oklahoma were apprehended, it did come out how the goverment’s agencies knew about these kinds of groups but let them operate while they are continually breaking up leftist groups.

It’s not overt; there’s no Stasi. But there doesn’t need to be one. What has been overt recently is the passing of laws and doing things in states to destroy unions. The thing that the US fascistic oligarchy knows well is everything hinges on a job in the US; all you need to do is make jobs hard to get and tenuous and you have 90% of your fight won.

If health care is ever passed as a system, it will hinge on having a job.

I think some similar things have been done in the case of the Freedom of Information Act—passed after the debacle of Watergate. At first records were opened, but these were not easy to get ever, and gradually it’s been harder and harder.

One thing worrying is medical records. More and more of the HMOs and other larger medical organizations and insurance companies are putting medical records into software programs. Can these be broken into? Would the HMO cooperate with a federal agency and hand over records that could be used to hurt someone? Right now in the US it’s very easy for banks to get many people’s financial record. It was before the Internet, but now it’s supereasy.

I agree on how language is so all important. One reason everything Bush says is a lie about any organized useful action in Iraq is I’m told a ludicrously small number of Americans in the state and other departments speak any Arabic languages. I read it’s 13 :)

Yes my question also was, what are these people in charge and power doing today and how do they relate to the ones who used to be in charge. Often we find cross-overs. I know nothing of how the German state works to suppress labor and socialist movements, but surmize it might be like the US policies. The invention of NATO and the money given to Europe after WW2 was intended to stop socialist movements. The US has intervened again and again in Italy to stop socialist movements (and Turkey and Greece).

I didn’t catch that joke at the end. Yes the student was sitting behind Wiesler steaming open envelopes and licking them shut. Thank you for translating "Graf." He did make his playright look very elite: cross-overs. I believe a number of Lessing’s top and more effective communists come from elite groups. That’s where they learned how to network and socialize to get what they want.

E.M.

— Elinor Mar 14, 7:39am # - Dear Fran,

Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck) was depicted as flotsam and jetsam to be picked up by males—to use Mary Astell’s phrase from her 17th century Serious Reflection upon Marriage (written after she had read Hortense Mancin’s memoir of her life with her husband and escape to being the mistress of a powerful man as the only option offered her of a decent life—the judges having read the cruelties and outrageousness, indeed madness of her husband said she must return to him, and that’s that), Mary Astell wrote of the way marriage is set up in European society:

"So we then fall as Strays, to the first who finds us?"

And she answered yes. But did not go on to say that’s because customs set the situation up this way, only implied it. She justified the situation by the Bible and God’s intentions, but she did make it visible in a startling bare graphic way, and did go on to talk of how powerless women were against men in the way marriage customs were set up.

"Men are possessed of all Places in Power, Trust, and Profit, they make Laws and exercise the Magistracy, not only the sharpest Sword, but even all the Swords and Blunderbusses are theirs; which by the strongest Logick in the World, gives them best Title to every Thing they pleas to claim as their Prerogative: Who shall contend against them?"

She points out how laws and customs make women without money, power, ability to move, and "confine" them "with Chain and Block to the Chimney-Corner."

On education, men are taught to cope with society, in the world, taught to read important and good books, girls not at all.

And so on, Mary Astell.

And Christa-Maria was one of 5 women in the film. Briefly we saw a secretary (woman) taking notes in the interrogation room. Briefly we saw Dreyman’s new mistress (yet sexier than Christa-Maria). And we had the neighbour next door who is threatened and helps Dreyman tie his tie. Ah yes and a prostitute Wiesler pays for sex.

So of 3 women two are utterly easy to be corrupted—when Christa-Maria offers sex to the interrogator you gather she has long learned this is the way to win through. The third is silently an instrument, and the neighbour terrified.

It’s often said movies have a preponderance of males over females. Amazing Grace had only 3 women leads, and it was the "love of a good" woman which brought Wilberforce out of his depression and Barbara Wilberforce is presented as having Godwinian and Wollstonecraft ideas galore, but after that all we see of her is endlessly pregnant and adoring her male. There was Mrs Thornton who helped Wilberforce and Barbara get together. Hannah More turns up to each meeting but we never see her do anything but show off where she lives to Equiano.

However, what’s really troubling is the idea this is the way women are; these customs would not evolve this way if somehow originally women weren’t passive and willing to be strays picked up. That’s Millar’s theory from the 18th century which I summarized.

I did begin reading Deborah Cherry’s Painting Women at long last last night and would like to say it’s very good. I bring it up because in the introduction Cherry actually attempts to counter this idea. Cherry quotes an Elizabeth Cowie who argued that we see women this way (reactive, strays, flotsam and jetsam) because we are not permitted to see them in any other way. She sees women as placed in kinship systems which don’t permit another story, theirs to be heard. I realize this is not a strong theory as it does not answer why women originally became part of these kinships systems—which of course cast any women outside them as freakish, to be distrusted, used, desperate &c&c.

It could be the system was originally set up this way based on brute strength. Women endlessly getting pregnant (breast-feeding, at the beck and call of all these children, sick from too many childbirths in primitive ignorance) were vulnerable, and once in place, the system stayed as people who get into power never give it up without a fierce and continuous struggle to take it back again. This is John Stuart Mill’s explanation in The Subjection of Women. Mill says though that now (the 19th century) we no longer are basing everything in brute strength women can win freedoms and a better life for themselves, and says it’s custom that is strongly enforced to keep them from changing things.

So the film (by a Count no less) is an enforcer of the same set of customs which keep women strays eager even desperate to be picked up and therefore not to be trusted.

If you were a stray dog you know your master can drop at any time with impunity, why should you remain loyal when you are about to be smashed by some other master?

I believe Val in Byatt's Possession referred to herself as a stray kitten the type of Margery Allingham type-gentleman-hero detective had picked up, expensively clothed and was now being ever so kind to.

E.M.

— Elinor Mar 14, 8:05am # - A little more. This evening when Jim and I were talking about the movie (he read the blog once he was up to it), he suggested what we see or saw in East Germany was a continuation of the real police-state set up by the Austria-Hungarian empire. From about 1848 to sometime in the 1860s half the population of some of the big cities were paid and coerced into spying on the other half. They might do it for more than money: in The Village and the Jungle, Leonard Woolf characterizes many local rural cultures as seething cauldrons of petty resentments and tenacious revenges, half-crazy when you listen to what people think and do. Jim said the empire gave it up because it was too expensive, but the apparatus was left in place as well as the mindset.

I can vouch for knowing the terror of Jewish and peasant relatives who lived in and around Germany in areas of Poland (much fought over). I know their terror is not a silly or paranoid thing—Americans meeting such people in the early 1920s through 50s don’t understand this. As I’ve written on my blog my great-great grandmother died in a prison somewhere in Austria-Hungary—without trial, it may be said. What trial? It would be a farce. And it was just a matter of a poor Jew who had displeased and aroused the guilt of wealthy powerful people, who had been such a fool as to go work for them as a babysitter. She was accused of baby murder. So the topic is part of our terrain you see.

E.M.

— Elinor Mar 14, 6:34pm # - From Fran:

"Jim makes a very good point, the so-called K.u.K. (kaiserlich und königlich/imperial and royal) Monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian empire was infamous for the efficiency of its secret police network. People who talk about the prescience with which Kafka, for example, anticipates the mechanisms of totalitarian regimes (such as Stalin’s and Hitlers in The Trial)forget that he was also actually talking about something his home town Prague had already experienced under the K.u.K regime.

As a German-speaking Jew, he also had first hand experience of the kind of ingrained racism and historically justified fear of pogroms you say Americans had difficulty in appreciating. He was actually in a double bind – already suspect as a Jew and equally suspect as being of German origin at a time of growing Czech nationalism and thus anti-German sentiment. It’s not surprising then that he should so convincingly create the atmosphere of existential fear and paranoia which pervades his works.

It’s an atmosphere that comes over in part in The Lives of OthersZ, this banality of fear.

If you think about it, prior to the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the only period of real democracy East Germans had experienced before was the extremely short period of the so-called Weimar Republic, from the fall of the German empire in 1919 to Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933. Some people see this as the reason why the states in the former GDR are still a happy hunting ground politically for anti-democratic forces both on the far-left and the far-right of the spectrum. I tend to think it has just as much to do with the same forces that help pave the way for Hitler’s dictatorship in 1933, the economic problems the area has had since making the shift and which can be readily and cynically instrumentalized by such groups. The GDR was not only morally and politically bankrupt as a system, but also quite literally bankrupt as an economic state.

Fran"

— Elinor Mar 15, 8:12am # - Dear Fran,

The banality or everydayness of paranoia is what makes the 1950s in the US different from other eras of milder repression. My father told me accurate stories of how people were terrified to get this or that magazine, talk about this or that because it had become in the interest of people at work to hit at others if they could (and take their jobs).

I remember ugly fights between my parents (pitiable in retrospect): they could not have afforded a honeymoon. Groups like the church everywhere today in the US and political parties still in Europe (communist ones still doing this in Italy as of the 1980s), help the poor, disconnected and powerless. So if you belonged to the communist party or had a friend who did in the US from the 1930s through 40s, you could join in on let’s say a trip. My parents had a happy honeymoon (though my father said that by the third day he understood what a mistake he’d made) in a small cottage in a pretty place in New England. Paid for by the communist party. My mother would not cease talking (irony) about her resentment and fears and basically destroyed whatever happiness they may have remembered from it. She destroyed the photos. In this case her fear was ludicrous since no one was after a minor clerk in the Brooklyn Navy yard. They were the kinds of people easy to shut up

Jews in Eastern Europe in the 19th century knew this before "Kaiser and Church", but after it, the pressure was scary and for good reason.

Myself I think we must bring culture as well as economics in here. Why is this let’s say 5-8 year period within the US still an anomaly. Why has Bush not succeeded in turning the US into a state where individuals are hounded with ease by the powerful cliques? Because for whites at least over 200 years, and for blacks too since the 1960s, there is a rooted tradition of individualism so strong that he can’t make real inroads. And it’s not the institutions which may and are being perverted insofar as he can (appointing judges who say Guantanomo is just fine—a recent decision in the DC court circuit). African and Muslim young men in my classes have said to me when they visit how they love the "freedom" of American life. They can’t get over it. (The girls don’t get this freedom but they do get more). They are talking about what I’m trying to get it.

There is deeply a live-and-let-live rooted way since the 1700s probably. It’s even more than the inheritance of common law through the British. I really can do what I please with my day as long as I can pay my rent and don’t try to hurt anyone else physically. I can’t express this more graphically than this simple truth. I need not marry the man I live with nowadays, but in truth I need not have before.

And you can do it even in small communities.

A deep instinct this is so brought people like Fanny Trollope here. But she didn’t have the money to support herself, and worse, she wanted to be middle class and be recognized by upper people. Ah, then living with Hervieu with children in tow wouldn’t do. No one stopped her doing what she pleased though.

When you dance to a different drummer you are going to have give up things, but not as many as you might suppose—as long as you can make money somehow somewhere.

People talk of the centrality of money in US life but don’t grasp its true positive effects :)

This is an important topic and I wish we could find a book by a woman about it we could read together and discuss. It was adumbrated famously in a book by Poper (?) called "the open society," but he as a member of the upper class stressed the establishment’s way of seeing this and (as in books on India) you are only talking about one thin level of experience when you talk of people in elite cliques. I compare the US to India: India’s been called a functioning anarchy; the US is more British than this, but it has something of the same actual allowance for diversity (this has nothing to do with multiculturalism).

I’ve been inadequate but tried to convey what I mean and hope I have something of it.

E.M

— Elinor Mar 15, 9:18am #

commenting closed for this article