Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Deborah Cherry's _Painting Women_ · 24 May 07

Dear Anne,

I finally finished Deborah Cherry’s Painting Women: 19th Century Women Painters, and want heartily to recommend it to anyone who wants to learn about the Victorian world of professional art, particularly as it affected women and as they were part of it. Its only drawback is the stills are in black-and-white, so while she discusses the career of the Pre-Raphaelite Evelyn de Morgan, to see Morgan’s painting in color you must go elsewhere, say Jordi Vigue, Great Women Masters of Art:

Evelyn de Morgan (1855-1919), Hope in the Prison of Despair (1887)

Cherry begins her book by pointing out there is a divide between North American scholarship on painting (that includes Canada with the US) and Anglo-British. In the case of North Americans, say Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin’s magisterial catalogue of women painters, 155-1950, Elsa Honig Fine’s Women and Art, the Peterson survey, Whitney Chadwick’s books, Alice Munro who wrote of modern American women artists, the writer slots the woman painter into a known movement hitherto represented only by men. Thus the aims, goals, typical images &c of the impressionist movement are rehearsed and we get pictures by Cassett and Morrisot and other women which exemplify this movement; or this or that modern movement is described and we get a specifically woman’s take on this movement, say by Gabriele Munter or Marianne Werefkin. The woman who just doesn’t fit gets a separate chapter, e.g., Kathe Kollwitz. Women who don’t really fitare made to fit somehow (Vigee-LeBrun, Angellica Kauffman). Popular books simply do this as a matter of course except they follow the idea of the “parade” of great individuals: Jordi Vigue’s book on masterpieces of art by women is just such a volume. Men are treated in the same way: the parade of “big” individuals and famous movements. Men fit the latter better as they started and defined the movements of art used to define women’s art.

In British and some European scholarship the case is varied but the idea is not to slot women into these preconceived movements men made. Germaine Greer’s book, The Obstacle Course is an attempt to situate women’s art in the context of their individual lives and show how they were subject to men and impositions, particularly about their sexual life, which crippled their careers. Frances Borzello’s book is a variation on this: she looks at paintings where women painted themselves (Seeing Ourselves). There is still the parade of individuals— this is what the popular audience likes best, connects to. But there is also (according to Cherry, perhaps self-servingly as she is British) an attempt to discover new contexts which are not rooted in individual oppressions or lives. In Cherry’s book this means concentrating on the reality that women characteristically have painted women and domestic scenes throughout and looking to see if there are movements within that, both in style and content.

Cherry genuinely looked at hundreds of paintings by women and

discovered what was common to them and described genuine movements in art the women followed: domestic pictures, pictures of other women, pictures of landscape and countryside, kinds of subject matter, techniques (strong on color, particularly water color). She then studied the careers of women painters and who they really sold their work to and who bought it. The result is a full information picture of the art marketplace in the Victorian world. Some of her findings might surprize. She finds very wealthy industrialists of a strong conservative cast liked to buy pictures of miserable homeless workers in the fields—as long as they were made statuesque and monumental. Of course portraits and history paintings (these done by men) were the most popular; after that landscapes (which women often did) which were idyllic.

Cherry uncovers or simply shows how a tradition of painting women in domestic scenes evolved. She also shows how such images do more than reflect reality: they help produce it. Rather like modern movies putting in front of young girls anorexic types so the teenager wants to diet, so these often falsifying or at least one dominant note depictions produce a norm or set of mores. She suggests one reason the 19th century picture by women is not liked and not that respected is the modern feminist or

working half-career woman does not want to see herself in (often alas sentimentalized) pictures cooing at children or being properly

bourgeois (upper class which is not representative of today’s

audience), and the males are embarrassed, cut off, and will only

speak of techniques.

Yet these pictures as Cherry shows often also create a dialect which subverts the intended message and even when not they depict women’s worlds. Among most successful I’ve put up on this blog and our groupsite space for Women Writers Through the Ages at Yahoo from the 19th century are Helen Allingham’s and Elizabeth Armstrong Forbes’s; they really do share motifs, some of which come from novels. The idea of finding what women as a group saw themselves painting and spoke to one another and other women viewers is a good one and brings forth new conversations

Surprizingly perhaps women did not paint children so much (in the way say John Everett Millais did), nor were they as sentimental or

anecdotal as is usually presented in museums. And some men painted in the genres and using techniques associated with women. John Atkinson Grimshaw’s cityscapes are a rare instance of a male artist whose painting is in character similar to what painted among women painters: local in place, emphasizing color, quietly domestic.

Elin Danielson (1861-1919), Reading Time (1890)

Women painters made careers who were part of the elite or just below it, and who had male relatives who were painters or became painters or were involved in art. They were also supported by sisters and mothers and lived with female relatives when they were not married. They had to work to keep up an image of respectability; losing that meant the destruction of a career. No relatives and friends and connections meant often no support and getting no where (whence Emily Jane Osborne’s famous frank depiction, Nameless and Friendless of a woman painter trying to sell her goods and getting no where, a cold face, cold shoulder:

Emily Mary Osborne (1843-1893), Nameless and Friendless (1757)

How many times I’ve confronted such myself in just trying say to to get persuade someone to be interested monetarily in something I’m interested. Suddenly the friendly face freezes and the words come out cold and tough. (Go away. You are not part of my clique where I have to do something for you since someone else in the clique did something for me. What could you have to offer me in return?)

For tonight let me send along two images and discussions taken from Cherry to suggest the kind of thing she does. I hope in future to put onto this blog out lives and paintings from Cherry.

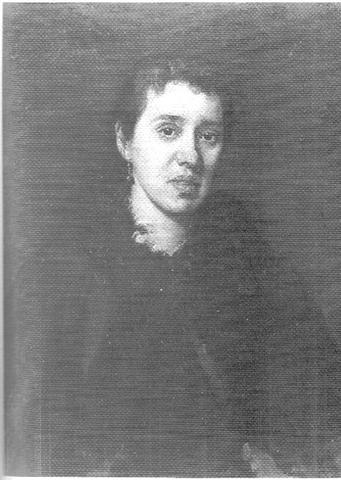

Nineteenth century women did heroic ideal paintings of one another. They didn’t prettify themselves or their friend, and instead presented the friend with her real features. Susan Dacre (originally sent by her family to Paris to train as a governess) and Annie Swinnerton were among these pairs of women who lived together and supported on another; they belonged to the Manchester School of Art: Dacre became president and Swynnerton the secretary. They organized exhibitions, life classes, and offered experience in art administration (important). What we have here is a presentation of a new public identity.

Annie Swinnerton (1834-1933), Susan Dacre (1880)

The idea was the stylish quiet black (or dark-colored) respectable

dress (respectability was of enormous importance in achieving any kind of success, i.e., making living). In Swynnerton’s picture, Dacre looks grave, strong and striking. It reminds of the several painter’s depictions of themselves staring out at us (e.g., Milly Childer). Dacre stares out at us but we can see dark marks around her eyes, and a certain real hesitation in her eyes. Cherry says Swynnerton paints Dacre’s face

“in terms of its unevenness, its unlikeness to contemporary

standards of feminine beauty. Deep shadows under her eyes, a large nose, full lips, asymmetrical eyes, wisps of hair escaping over her forehead comprise the depictionof her face while a loose, enveloping cloak entirely concelas the contours of her body. This dark fabric and a plain monochromatic background throw the pale face with its shy, slightly anxious expression into sharp relief. Lighting, composition, coloruing, the gravity of tone and presentation as well as the academic handling of paint emphasise the face as the picture’s central focus.”

Cherry says the picture is determinedly not fashionable; fashion

would mean offer “svelte lines of fashionable styling which disposed the body into serpentine curves … accentuated by elaborate trimming.” Commisssioned portraits of the rich would have a rich surface, creamy paint. Dacre does not stand there as an object of masculine desire either.

Although in black-and-white, I feel the original beauty of this landscape still comes through:

Ellen Gosse (1850-1929), Torcosse, Devon (1875-79)

Ellen Gosse’s husband, Edmund, is still remembered—for his autobiography, Father and Son, his scholarly writing and research, and friendships with people like Henry James. Ellen has been forgotten.

She was a landscape painter—or at least meant to be one (as the woman in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse). Daughter of a London homoeopath, Ellen “attended Ford Madox Brown’s classes,” and began exhibiting her work in 1871. She had a studio that she shared with a widowed sister, Emily, one of their brothers, and an aunt. In 1874 her aunt wrote to Edmund Gosse (probably a relative) that

“Miss Nellie’s determination of will, she having willed that she will not marry, but prosecute her artwith all her might, for since she has no fortune, she wishes to be indebted to no one for a livelihood, but work herself into fortune.

Ellen at first refused to marry Gosse on the grounds marriage to him would remove the time she needed to paint, but in the end yielded. He worked as a civil servant while gaining a reputation as a civil servant and poet; she “ran the household, kept their accounts” (it was she who collected “payments outstanding for Gosse’s work and secured remunerative commissions”), and looked after their three children (Philip, Teresa, Sylvia). While she was away from home (not painting, but taking her children on a holiday, visiting his parents, nursing a dying father), Edmund would send her notes like this which has survived:

Please let me know by return of post:—1. Where are my white flannel trousers and shirts?

2. Have I a decent pair of tennis shoes?

He confessed he depended on her for all daily comforts of this type, and said “how fatiguing” it was when she was away.

It was, however, on these visits from home that she did manage to paint her landscapes. Later in life she also wrote: travel pieces, nonsense verse, art reviews (to the Saturday Review, Century and Academy), children’s stories (St Nicholas) and published articles in the St James Gazette. She wrote an acid letter to someone in 1893 when she was sent a copy of Art and Handicraft in the Woman’s Building of the World’s exposition in Chicago. It might not have been that she was once a woman painter, but that she had the right social identity (which of course enabled her to exhibit in the first place).

Her painting can be seen as part of a “vigorous contestation of

meaning around land, the countryside and rural life.” Trollope is

among those who continually writes to say how the English countryside is beautiful in the vein of no need to run to Italy to see beauty. Ellen Gosse did not quite paint rural England in the way Helen Allingham has been accused of (bastion of ancient traditions, nostalgia), but she does not paint it as outmoded and antiquated (which can be seen in Allingham’s paintings of bedraggled exhausted women with children outside old cottages). Rather it’s a vision of beauty like the watercolourists Christopher Newall reprints in his Victorian Watercolours, images from which I’ve put on Trollope-l from time to time.

I’ve found nothing on the Net about her except mentions of her name in articles about Edmund Gosse, Laurence Alma-Tadema (and his daughter, also a painter):

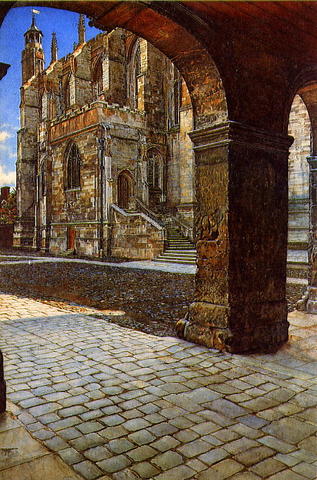

Anna Alma-Tadema (1869-1943), Eton College Chapel (1885)

However, in Deborah Cherry’s book you can discern the outlines of her career, why she at first refused to marry, and what her social identity enabled her to do as well as prevented her from achieving.

Cherry has a full index of names, a bibliography and I just can’t

recommend it too highly. It’s as valuable for the text as the reprints because what she says is grounded in real hard work of finding out and information, real seeing and describing. She just cast aside the steroetypes of “realism,” “impressionism” and the rest of these (actually small) movements of the famous to look at the vast world of Victorian art as practiced by women in the real world.

Katherine Beard, Spinning (1890s)

I keep also meaning to put on the blog more “foremother poet” postings. Somehow I get up the energy to put these on lists (Women Writers at Yahoo and Wompo), but not transfer them here out into general cyberspace. (It’s more work for me as I can’t resist including many pictures.)

Sophie

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- An addendum: here's a URL to a UTube film, which has been

making the rounds on several of the lists I’m on and gotten an extraordinary amount of hits:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUDIoN-_Hxs

If you click, you’ll discover to a slow slightly off-tune violin, you get a long series of famous portraits of women morphed into one another.

On just about all the lists I’m on it has been also been remarked that what we have here is the male gaze, and a male point of view on women. The woman looks at us coyly, alluringly, mysteriously, with a kind of “come hither” expression. The many paintings by women not only in Cherry’s books but in all the others show women painters struggled to present women on their own terms, not as sexual toys with a narrow set of controlled and alluring features.

I’m sure if we had a longer view (say down to the waist), we’d see firm upturned breasts (not long or hanging ones), a backside that is not too low and not too high; in short, white body features too.

If given an archetype like Medea, they would characteristically paint her differently.

This UTube shows how little about a quarter of century of scholarship on women painters has penetrated to the mass audience.

If you try to remember the last movie you went to with a famous star, let’s say because they are older, Away from Her, you will find the “heroine” is a type like that in UTube: Julie Christie’s features are those of UTube. Olympia Dukakis who is made the “hero’s” mistress has features which are quite different: square, and not alluring, no upturned nose. Our movies reinforce the male view continually. Who gets to be a big star is the woman who looks like those on the UTube presentation.

E.M.

— Elinor Jun 3, 2:21pm # - From WMST-l

“The discussion about the YouTube video “Women in Art” is really fascinating to me. Someone sent me a link to this video a few weeks ago and I thought it was amazing and wonderful. I guess no one is questioning the technical proficiency but I didn’t think I was responding only to this aspect. The montage is composed, I guess, mostly of European art and, of course, as much classical art does, these portraits reflect conceptions of beauty that were dominant at the time. (Especially when the subjects or their families are commissioning the painting, there is an incentive for the artist to depict the subjects in ways that those paying for the portrait will find flattering.)

When I watched the video, it never occurred to me that it was like looking at the subjects through a gun turret sight. Or that the apparent motion was like attempts of the subjects to turn away, despite chains. I’d seen the same poster’s similar montage titled “Picasso” (at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjoWCdzhuFI) and the gun turret sight idea and the idea of subjects trying to escape but not being able to because of chains hadn’t occurred to me with respect to that video either.

And, while some of the subjects may well have been underfed, exploited and even wondering whether they were pregnant by the painter, it looks to me as if many were very privileged women who, within the confines of the social structures of the time, were likely to have wielded a fair amount of power. Certainly, many of the subjects don’t look poor or downtrodden, though this could be misleading, I guess.

I think that some of the portraits depict women in demure poses (though some do not) and maybe in ways that don’t strike us as exhibiting strong, independent women. But I wonder, at least with respect to commissioned works, how much of this can be laid at the doorstep of the artist. I’d have to know a lot more about art history to answer all the questions I have about this.

I’ve viewed the video several more times after reading the discussion on this list and I guess I just can’t see “Ophelia slowly tumbling in a stream,” nor chains, nor the imagery of viewing the subjects of these portraits through the sights of a gun. It’s interesting what each of us brings, or doesn’t bring, to the things we see.

Cheers,

Claire Hughes

— Elinor Jun 4, 5:52am # - IN response to Claire Hughes,

I would strongly qualify the view that the women in the paintings were “very privileged women” who “wielded a great amount of power.” Many were models who made a poor living this way, part of which was dependent on allowing themselves to be the sexual partner of the painter. This is not well-documented for the Renaissance; it is somewhat documented from the 18th century on and more thoroughly in the 19th century. Just have a look at the lives of the women who were models from the later 19th century on.

Those women painted who might have been members of wealthy families would also have a very limited power as they were not the people who owned the property or controlled it at all (men did), and were they to displease their families, would quickly find themselves punished or cast out.

Sexual power itself is transitory, dependent on the woman’s age and not having been sick as yet very much. And also on particular features thought desirable. When at the MLA conference held in DC around Xmas 2 years ago I heard a memorable paper where the speaker had researched the specific area of “long” or “hanging” breasts in slaves. She discovered that women who had “long” or “hanging” breasts fetched much lower prices; those with smaller or upturned breasts where advertised to be bought as companions for men in their beds. Women with “hanging” breasts were likely to be put in the fields and not become house servants. The speaker suggests that “hanging” or “long” breasts are associated with black women and aging as well as ruination through breast-feeding and therefore could adversely affect a woman slave’s fate (if she had such breasts genetically or due to breast-feeding or age). She quoted letters from owners who would boast of this feature if the woman they were offering (say to a guest when he was to come over) had it. The value of the paper was the candour of the remarks she quoted from diaries and letters of slave-capturers (I don’t know if that’s the word), slave-owners and potential buyers, needless to say all men.

The paintings encourage a false idealizing of women on grounds that won’t stand up to pragmatic and historical scrutiny.

E.M.

— Elinor Jun 4, 6:21am # - "Hello Ellen,

That MLA paper sounds fascinating! Do you know if it was published? Do you remember the paper title? I know in some of the 1850s daguerreotypes by Joseph T. Zealy, for example, he depicts enslaved African American women with “hanging breasts,” and I had wondered about the practice because it was done in an anti-aesthetic, “scientific” manner (said daguerreotypes were exhibited in a pseudo-scientific book on “Types of Mankind”).

At any rate, I had noticed that the video montage avoided the more sexual images since the focus was on portraiture and not women’s bodies. Which is why I had made the comment on idealized “beauty,” which is all about facial features, more than on sexuality, which is about the body.

Thanks,

Janell Hobson

jhobson@albany.edu"

— Elinor Jun 5, 8:57am #

commenting closed for this article