Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Why study women's poetry · 13 February 08

Dear Harriet,

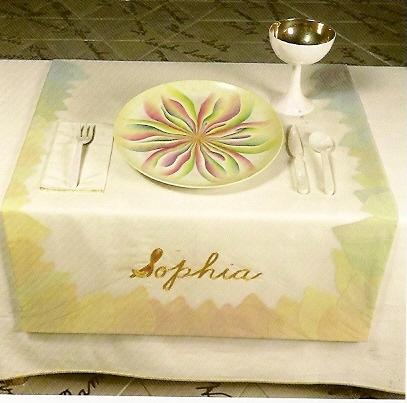

First, a picture:

Table setting for Sophia, goddess of wisdom (Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, 1974-79)

Sophia (writes Chicago in the book which accompanies the installation at the Brooklyn Musuem) stands for “the highest form of feminine wisdom … an entirely abstract symbol that possesses a spiritual wholeness in which the material world is altogether transcended.” Chicago writes Sophia was sought of as “providing nourishment and translation of the human spirit …” I put the following poem by Alice Ostricker on WW yesterday because it moved me and I recognized in it a transmutation of my own experiences:

Wanting all

More! More! is the cry of a mistaken soul,

less than All cannot satisfy Man. – William Blake

Husband, it’s fine the way your mind performs

Like a circus, sharp

As a sword somebody has

To swallow, rough as a bear,

Complicated as a family of jugglers,

Brave as a sequined trapeze

Artist, the only boy I ever met

Who could beat me in argument

Was why I married you, isn’t it,

And you have beaten me, I’ve beaten you,

We are old polished hands.

Or was it your body, I forget, maybe

I foresaw the thousands on thousands

Of times we have made love

Together, mostly meat

And potatoes love, but sometimes

Higher than wine,

Better than medicine.

How lately you bite, you baby,

How angels record and number

Each gesture, and sketch

Our spinal columns like professionals.

Husband, it’s fine how we cook

Dinners together while drinking,

How we get drunk, how

We gossip, work at our desks, dig in the garden,

Go to the movies, tell

The children to clear the bloody table,

How we fit like puzzle pieces.

The mind and body satisfy

Like windows and furniture in a house.

The windows are large, the furniture solid.

What more do I want then, why

Do I prowl the basement, why

Do I reach-for your inside

Self as you shut it

Like a trunkful of treasures?

Wait, I cry, as the lid slams on my fingers.

Two days ago Annie Finch wrote to Wompo:

“On April 5 there will be a one-day conference at St. Francis University in Brooklyn on the topic of “Why Study Women’s Poetry.” I proposed, for this conference, a presentation on the topic of Wom-Po—a list which seems to me to prove daily the importance of studying women’s poetry. The presentation has been accepted.”

Annie said she’s “love to have our thoughts on this fundamental question. In fact, I’d like to include in the talk a compendium of remarks from all of you, a kind of virtual virtual-world as it were (a real life approximation of the “real” virtual world!)—so I can bring your names and your words to those at the conference (and of course, hopefully some of you will be there in person too!)

So, please let me know. Why is it worth studying women’s poetry as a separate field? To quote the original questions posed by conference organizer Wendy Galgan—and probably posted here in the first place, though I can’t quite recall if it was, ‘Decades after feminist critics began considering women’s poetry as a genre separate from poetry written by men, the debate continues as to whether we should study poetry according to the gender of the writer. This conference will explore the question “Why Study Women’s Poetry?” by examining (even problematizing) the ways in which women’s poetry has been studied as a genre separate from men’s poetry.”

There were quite number of replies to her onlist, and perhaps even more offlist :) Because I can’t attend (or in compensation for not attending) I took up the challenge of answering. I also put my posting on WW where we have a poetry day each Tuesday and have tried to study some women’s poetry together (e.g., Anna Akmatova), and discussion Sappho and translations of Sappho and what these have meant to women (“through the Ages”) more than once.

Why Study Women’s Poetry

We must study women’s poetry for the reason we study poetry. I incline to think some forms or genres of poetry are conceived by the poet to be the most complete (in the sense of form coming up to matter) forms of utterance in cultures where we see articulated in a way nowhere else realities and feelings and needs of our lives. Thus it’s vital and imperative we study these utterances.

We have to inflect this imperative to say we must study women’s poetry because women’s poetry hasn’t been studied until very recently. When something is not valued, it will not be published, paid attention to and will be lost. Since I’ve been on the Wompo (over two years) I’ve seen pronouncements that startle me: women hardly write about their children (what?!); did women write blank verse poems? (of course); why didn’t women write epics? These assertions & questions are the result of countless centuries of men not publishing, and no one saving women’s poetry; when it’s published, it’s often misrepresented deliberately. Either it’s censored and not published in the original form, the most important lines (because different and disturbing to the public mainstream) omitted; or reframed so it will be understood in a way not intended (condemnation & supposed punisments are substituted for empathy and identification).

I was looking at anthologies of 18th century plays recently (to make up a list of plays to read with members of my small Eighteenth Century Worlds @ Yahoo list); and I discovered slightly to my shock, that still in 2008 were it not for the specifically feminist anthologies where all the plays published are by women, apart from a very few (Broadview Press) huge and expensive volumes where men still outnumber women 10 to 1, there would be no plays by women available for the common reader to read. We identified 4 volumes recently reprinted where not one play was by a woman. So if no one had published anthologies of sheer women and their plays, we’d have basically almost nothing to go on to study the poetry of 50% of the human race.

It is simply so that women’s poetry differs from men’s. It differs

because women have different experiences. Until recently in the west and in traditional societies still, they are kept out of public life mostly; they are still seen and treated as primarily sexual and familial objects whose central concern is to marry and bear children; their chemistry or biology is made even more central to their character than their genes make them. I can’t say whether this leads to a whole psychological difference; it certainly inflects outlook terrifically (consider the effect for centuries of endless pregnancies once you married; the inextricable connection of sexual experience to pregnancy). And study after study of older poetry (and newer too) has shown women do have characteristic imagery different from men’s, often do (perhaps in response to their marginalization) take on a self-deprecating or non-vatic stance. I could go into details: they have small animals (birds especially); they turn to certain kind of fairy tales; they develop subjective and private terrains; they gush to release socially unacceptable grief and loss; they have heroines at the center much much more; their experience of sexuality is different because of the social arrangements that shape that experience and they write about this differently. Arachne is an inspiration not fearful.

Not to know your history is not to have an identity. Memory and

self. What are we but what we remember. If we face a blankness, that either denies we exist or at best presents a much skewed, censored and not respected body of work, where are we to know ourselves. People know themselves in context, not in a vaccuum. Oh had I read Mary Piper’s Reviving Ophelia at 19; I think to myself how it would have helped to know other women felt as I had, had had experiences as I had—and put sympathetically, not judgementally, not beratingly. All I had were the old classics and a skewed set of books in popular culture. What the women’s movement has done is widened the kind of books that are written and advertise them more truthfully (though not enough, no where near enough).

We must go back in time for the reason all people should study

history. The parallels between women today and women in 17th century England and France (an area I know about) are startling, and illuminating. And the contrasts too. It’s asked why so much women’s poetry seems bad; well what are you judging it by; how do you understand it; what are you looking for? I’ll move into the area of art because I recently read an excellent book (by Deborah Cherry) on women’s painting in the 19th century. When you look for impressionism and some of the later movements, you come up with inferior women, women copying, but when you study women’s paintings apart and in large enough numbers (which you begin to have at the end of the century when they can go professional), you discover they didn’t want to paint impressionism as a group: their paintings are about domestic life; they turn to different archetypes; they use colors rather than line; their typical anecdotal subject matter is different (aspects of women’s lives and childrens). You have to develop different criteria.

I’d be disgenuous if I left out this problem: the problem of low

expectations and the feeling that if you do something it won’t be

valued so why put yourself out. Women face low expectations. Now that can make existence easier in some ways (only if you are lucky and get kind keepers and family members, or are born to money and upper class in some countries where women are allowed separate lives in schools), but it also depresses the person trying to achieve. A familiar example: Austen’s two virtuouso books, Mansfield Park and Emma are virtuouso because she had finally had two successes, finally made some money and she knew she was going to get them into print. So there is that. Fear of reprisal, of envy (from other women too who fear they will be seen as inferior and not valued), of disdain twists people and some of the genres women have chosen in poetry (friendship, retirement) come from this.

I did like Alice Ostriker’s [a member of Wompo] point: “First of all, there is the discovery that marginality, however painful, may be artistically useful. Some linked motifs announce themselves: the quest for self-definition, the body, the eruption of anger, the equal and opposite eruption of eros, the need for revisionist mythmaking. ” But it is hard to put across since people so value triumph and power (women as well as men) and have hard time asserting a different value. I gave a paper in an 18th century conference where I argued on behalf of mordant poetry, morbidity, anger, sadness:

“I hate such parts as we have plaied today”. I concentrated on epilogues and what a few women poets managed to say about the typical women characters they had to watch on stage. Needless to say, no one spoke to the topic after I finished. The person heading the panel, a man, looked like he was going to sleep. He prefers cheer I suppose. Now for years even decades apparently Judy Chicago’’s Dinner Party languished in a basement. A particular woman (the donor and patron) with a deep pocket persuaded the Brooklyn Museum of Art (which is outside NYC and therefore has trouble getting the attention of the Met or MOMA in Manhattan) to reset up that exhibit. It’s celebratory and defiant. Not everyone has it in her to be celebratory and defiant, and also (as she does) get in the sad stories of the tales of women, bad things done and done a lot and then lied about, erased, incessant present to be self-sacrificing (to the point of continual risk in childbirth before the 20th century, and it was painful and awful). The reason we must study women’s poetry is put before us in the beauty of this installation and its content.

Now here in 2008, we might say even to have to ask this question as if women’s poetry needed particular justification is disturbing. It shows how we have not gotten where we should be. (Yesterday’s election in Maryland, Virginia [where I live] and DC was disquieting because of the manner of its reporting, and in that we see why we must study women’s poetry). We must reconceive what we must by a career in poetry. One criteria cannot be continual publications or a full-time paid job as writer-teacher of women’s writing & poetry. We must look back and when we discover a woman who devoted her life to poetry, & wrote in forms commensurate with her ethic, gender experience, and time available, call her a poet.

I have had women students who have not heard of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own or Three Guineas much less read these. Middle-aged women who need (made to feel terrible about themselves, especially when they’ve not had any children) who have never heard of Germaine Greer, much less her The Change. But I am getting too excited.

I close with a woman’s poem. In response to the poem I found by Alice Ostricker, Judy put this poem by Barbara Crooker on WW:

“I liked the Alice Ostricker poem Ellen posted, with its picture of a couple who still have things to learn about each other after all

those years of marriage.

By coincidence, I’m also posting a poem about a married couple – this one is today’s selection from the Writer’s Almanac newsletter, and is taken from the collection Radiancc by Barbara Crooker:

In The Middle

of a life that’s as complicated as everyone else’s,

struggling for balance, juggling time.

The mantle clock that was my grandfather’s

has stopped at 9:20; we haven’t had time

to get it repaired. The brass pendulum is still,

the chimes don’t ring. One day I look out the window,

green summer, the next, the leaves have already fallen,

and a grey sky lowers the horizon. Our children almost grown,

again how to love, between morning’s quick coffee

and evening’s slow return. Steam from a pot of soup rises,

mixing with the yeasty smell of baking bread. Our bodies

twine, and the big black dog pushes his great head between;

his tail, a metronome, 3/4 time. We’ll never get there,

Time is always ahead of us, running down the beach, urging

us on faster, faster, but sometimes we take off our watches,

sometimes we lie in the hammock, caught between the mesh

of rope and the net of stars, suspended, tangled up

in love, running out of time.

Table setting for Sappho (Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, 1974-79)

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I put the lovely image of Sophia on the WW (Women Writers through the Ages @ Yahoo) groupsite page last night. It consoled and strengthened me after the manner of reporting the defeat of Hillary Clinton in three primaries last night.

I’m allured by its cool austerity. The soft yellows, white, and the rare pinks with the simple knife, fork, and spoon and cup appeals to me very much.

In the paragraphs on Sophia in the recent book of The Dinner Party, Chicago connects the design with ideas of wisdom in Gnosticism. She conceives of Sophia as “an incorporeal entity, the active thought of God, that created the world.” Sophia was “often portrayed as a single, delicate flower,” and the imagery used was that of the flower (petal iconography).

Chicago drew on an illustration by Dante (it’s said) presenting Sophia as the supreme flower of light. We can see flower petals on the setting; the material is chiffon; a floral wreath is suggested.

Grouped around this place setting on the floor are carved the names of legendary female figures of the Greco-Roman world and heroines of Greek tragedies (e.g., Antigone, Cassandra, Sibul of Cumae). The paragraphs found describing these figures are all in another room of the installation: they are put on a wall next to the figure’s names. Apparently what’s there now and in the new book represents a revision and expansion of what was under each name originally.

I mean to put up more of the imagery from The Dinner Party on WW for the next month or so. I've made an archives of images from The Dinner Party at WW; thus far we have but 24.

E.M.

— Elinor Feb 13, 10:30pm # - To this Fran replied:

“It is an attractive setting. Though I otherwise enjoyed my one and only visit to the Brooklyn Museum, I was disappointed not be able to view Chicago’s installation as some work was still in progress at the time. Especially good then to view it at least vicariously here.

Gnosticism is a fascinating subject – there’s an ongoing discussion of ‘Montaillou’, a book on the last bastion of the Cathars in Southern France over on French Lit. which I wish I could find time for. We were very moved by what we learned of their fate on our several visits to that region.

On the subject of the feminine in wisdom, one of the many things that did for them from the point of view of the established Catholic church was, of course, the fact that they had highly respected women priests and seers in their

ranks, not to mention their very idiosyncratic, positive view of the Fall and the role of Eve and the Serpent in particular.

Fran”

— Elinor Feb 13, 10:34pm # - From Marie on Wompo:

“caught between the mesh

of rope and the net of stars

Oh, that’s lovely, and what an apt poem re: the ongoing conversations about women’s poetry.

Thank you for posting this!

best,

Marie”

— Elinor Feb 14, 12:06pm # - Clare:

”’Though darkness gathers, praise our crazy fallen world; it’s all we have, and it’s never enough.

Barbara Crooker’

What a superb last line. It’s one of those you could hold on to in

the darkest hour.

Clare”

— Elinor Feb 14, 12:07pm # - I sent this to Wompo and WWTTA, but alas got no reply:

On Wompo they’ve carried on with this topic and two days later it’s morphed and sometimes they are debating what happens when a woman allows herself to be the 10% or less women to appear in an anthology or periodical, and women who refuse to allow themselves to be published in a woman’s anthology. Usually these are the rare lucky women who are respected and read by men.

I’d like to send along here what I wrote after reading a slew of these. I didn’t involved myself in the controversies about publishing since I have no professional commercial career. I thought maybe I could interest people on WWTTA by reframing the question and also talking about prose works by women (which we’ve often done). So my question here is, Why read womens’ books? And especially from a woman-centered and sometimes feminist point of view? Why is our list vital and necessary (even if the world doesn’t seem to pay much attention to us :) )?

So here’s what I say in this light:

I study women’s poetry because I often like it much better. I prefer it. Just as I read women’s novels, memoirs, and plays much more often than I do men’s. I opened a women writers list on Yahoo so I could do this with company and find out more good books by women; originally I hoped men would join my list, but only a couple have (well only a couple I know about as they post) and it’s lovely to have their views which can be different from women’s—they often are not at least as written about on this list. For late at night when I get up often for a couple of hours I like to have a certain kind of book going for comfort. Right now it’s Rosamond Lehmann’s Invitation to a Walz. A month or so ago it was Margaret Foster’s Lady’s Maid. They strengthen and sustain me and I can get back to bed and sleep again. I do have phases where I’m reading one woman’s books intensely this way. One time it was Valerie Martin. Another Margaret Oliphant. (I can’t remember ever doing this for a man’s books—maybe Henry James, ghost stories by men.) Then ever after I look to see what that woman has published and try to keep up. Emma Donoghue is one such writer. Isabel Colegate. George Sand. Ah, I like French women writers very much but I’m slower reading their books, and for Italian ditto and I’m slower yet. I love Chantal Thomas’s books (Souffrir, Les adieux a la reine, I read them in English too: Coping with Freedom, the book about the real life of little girls). I’ve read a couple of Elsa Morante’s books in the Italian. Very great (Storia is one of the great novels of the 20th century—in the league of Christina Stead’s). I keep up as best I can.

Women’s poetry, novels, memoirs, letters, books speak home to me about what I care about in terms that I have experienced and seem true and accurate to me. Indeed I have a hard time reading a certain kind of male book which is not at all inflected by the “feminine” outlook. I love Henry James, Proust, Trollope (who write subjectively and can be classed with Gaskell; I would class him with Margaret Oliphant & Elizabeth Gaskell instead of them with him), male sonnets, LeCarre, Graham Greene, E. L. Carr (I often like the male writers chosen by Booker Prize, the Whitbread—Michel Faber for example). I did my dissertation on Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa , a great and important book for women in women’s literature (in understanding what happened to the novel), and read male poets and writers but they must have a certain amount of this component or I cast them aside bored. When the book turns into an adventure story, I stop reading. I agree on Longfellow writing in this feminine way; so too Tennyson and quite a number of the male Victorian poets. I can’t get myself to process certain kinds of books by males & females too, and when I come across what I recognize as (or see as) misogyny I stop reading or have to force myself (if it’s something I have to read for some professional purpose). If it’s amusing and satiric (say Pope) well I can read that if it seems to be accurate. I do like witty satire and men are good at that.

Why study men’s books—well in part to understand women’s. Women are influenced by men. Recently Lucy Hutchinson’s poetry was published for the first time. She’s a 17th century memoirist. Her poems are heavily influenced by Donne and Milton. As a woman in the era situated the way she was (puritan, and most women writers were cavalier in outlook), she didn’t read women—anyway they didn’t publish at all, or only through manuscript. But when I read her poems and compare them to Donne I can see strongly the difference in outlook: her love poems to her husband are strikingly like those of love poems of 16th century women to lovers, and unlike Donne’s who objectifies women and treats them as objects for metaphors. Starting in the 18th century women were able to find one another’s poems more easily and were influenced by one another, aware of one another. You see this phenomenon in the 16th century (women sonneteers aware of one another), but it’s only small elite. It spreads enormously once there is a literary marketplace. In my view a set of books of enormous importance for women are the French women’s letters of the 18th century: this come out of the 17th century movement and seem to me among the first in western literature to be frank about sex and life.

It seems to me those who doubt that women’s writing differs from men show they have not read enough women’s writing in context. You need to write women’s writing in the era it was written with lots of other women and men and then you see it. Looking at patterns, yes, but also subject matter, and aesthetics too. But I digress.

It’s fascinating to read famous men in the context of the women they were involved with. Just now I’m reading Iris Origo’s The last Attachment. We see Byron from Teresa Guiccioli’s point of view, and recently (literally a couple of hundred years after first written) her Vie de Byron was published; people may still call her a silly woman, but if you read her book, you discover she was not and seeing him framed by them enables me to return to him anew. He is one of the many male poets who have a strong feminine component. I’m wanting to read Origo’s books on herself, her memoir, I loved her Leopardi: A Study in Solitude.

There are women who write like men. Sometimes it’s a careerist stance; that is, they know they’ll get published if they ignore the woman-centered point of view and also if they write adventure stories and sometimes they want to do that; sometimes they want to separate themselves from women as they are ashamed and embarrassed to be a woman, to be treated as a woman. I see Aphra Behn doing that in part—though she also writes as a woman. Many women journalists today write from a male perspective to get published; or they write detectives stories say with a female hero (not a heroine, a female hero, a surrogate for the male giving her male roles). They crave the kind of power, public and influential widely, and admiration such things bring that men get. But I don’t enjoy them and don’t read them much or they anger me. Helen Vendler is one such critic; she lambasted Margaret Homans book and her review hurt Homans book badly because it was published in the NYRB which typically has 1 or 2 articles at most by women, often of women’s books, and the rest by men.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 15, 1:40pm # - A few hours later. Jumping off from "why study women's poetry," someone started a thread “Where we write from.” I was puzzled by the postings which assserted intensely how the person was an outsider.

I wrote as follows (and got no reply):

“I liked this one too—probably because I find it a question hard to answer. On one level, I’m tempted to quip: I write from 308 Cloverway, at a brown mahogany desk which is pushed up against a nice-sized window so I can look at and see the trees, grass, and private houses [NYC phrase for free standing house] in my neighborhood. Of late as I watch the sun go down (a favorite time of day for me is twilight, the time just as the light is fading from the sky) I’ve been thinking how I’ve looked at this scene for some 23 years, sometimes it’s summer, sometimes bare winter, then it’s dawn, or the sky is black, and then again it’s spring and a neighbor’s pink tulip tree which overhangs a fence near my window is in bloom.

I feel I write out of the whole of my past. Some experiences are much more vivid, and there are some never far from the surface, or easy to bring up—alas, these are the traumatic ones. It is true to say that who we are (or who I am) in the sense of what my position is in the social/economic relationships or arrangements of the world influences if not what I write (as that is the product of this past), then how I write it.

Since coming onto the Net I’ve been aware that I write as a woman. The famous New Yorker cartoon about how nobody knows you’re a dog on the Net, seems to me important because it’s so wrong (like a dream people might want to believe); all the baggage that exists in the physical world is replicated in cyberspace, partly because people reading what you say or put on the Net seek intensely to discover your gender, ethnicity and other things and if they can’t, they tend to invent it from surmizes, but partly also because we bring it with us. Or I do.

For me my particular past and memories are more important than whatever positions (very tenuously) I’ve held. Memories include what I read and nowadays that’s living talk on the Net as well as traditionally published stuff.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 15, 3:42pm # - From Clare:

“Phew, Ellen. Where to start? I do agree with most of what you’ve written. I feel that part of the enjoyment of women’s books is that the mind of another woman is familiar ground, in spite of different lives race, nation etc. there is a shared experience at the biological level that is common. A man is different. A man’s mind can be interesting, even fascinating ( like the man himself) but they are different, another land, other. However, some women’s books alienate us, because of attitudes, beliefs etc. I find the so-called chick lit. type of thing almost as off-putting as the macho thriller. They are both stereotypical and thus of little interest, to far out on the edges of the feminine/ masculine parameters. Perhaps these books show an element of bad faith, just written for a market.

“I agree on Longfellow writing in this feminine way; so too Tennyson and quite a number of the male Victorian poets.”

This is an interesting thought. I sometimes think there is an asexual literature, where the writer forgets their gender and writes as a human, in the sense that there is a middle ground, where gentle, nurturing men can coexist with strong, forceful women. I sometimes think there is a middle ground where the sexes are similar and can understand the other by sheer force of imagination.

Mmmm, does any of this make any sense? I suppose the fact that we are trying to generalise about men & women, where there are all sorts & conditions of each, from the super – feminine woman to to butch female through feminine men to the super macho male. All variations across a scale, all men and women yet different. The minds vary in a similar manner,so too the writing. Having aid that, it is true that even in a blind test one almost always gets the gender of a writer right.

I study women’s poetry because I often like it much better. I prefer it. Just as I read women’s novels, memoirs, and plays much more often than I do men’s. I opened a women writers list on Yahoo so I could do this with company and find out more good books by women

I think this is the kernel of the matter. We prefer it. We learn about ourselves thro’ reading other women. We feel at ease with their interests and mind-set. There is always an element of tension in reading a man’s work, we are working at one step removed. The imagination has one more loop to go through.

I’m sending his before I decide It’s all tosh and delete it. It has just occurred to me that this isn’t true of music. The gender “stamp” doesn’t work with composers. Maybe music, like mathematics, is “purer” more of the intellect & emotions, rather than coloured by gender. I’ll have to think that through.

Clare”

— Elinor Feb 15, 10:45pm # - I’m glad you take my view, Clare.

It’s interesting to me that you feel music is an exception. I’m persuaded from studying literature and the visual arts there are many smaller and more fundamental differences between the way men and women operate.

Why would music be different? In the visual arts you handle non-content things like color and line, and these can be shown to preponderate differently in the two sexes. Women tend to be painterly, men tend to move towards line.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 15, 10:48pm # - On Wompo Annie Finch did respond to mine by thanking me. Thus encouraged I went on:

Thank you, Annie, for responding to mine. I’d like therefore to emphasize one section where (I think) I bring up something that is not sufficiently paid attention to, or at least not presented in the way I did: the problem of low expectations and the envy and resentment women who achieve confront. I see it as having purchase not just in the field of poetry but most fields of life.

The exceptions are motherhood, getting married, and managing a family.

It’s simply easier to yield to not having to compete out in the marketplace world, and if there’s not only an alternative, but you are positively punished when you persist, why persist? I know saying this will get strong objections, but I submit with all the vexation, misery, blaming and impossibility of bringing up some family in the modern world (where much influence on the child and everyone in the family is way beyond the mother’s reach), it’s not as hard as the thrust and performative manipulation necessary for advancement in impersonal circles. You aren’t supervised when you are at home. I see what’s happening to Hillary Clinton as in large part explained by the resentment and envy her achievement meets with in men and women, women because they are not doing it and their identity is such they feel threatened by this; men because they want this space for themselves. There are only so many places of power or high salaried jobs.

The denigrating word, “bluestocking” is important when we turn to the writing field. The woman is ridiculed and it is incessantly asserted she must be unhappy with the implication that marriage or having a partner and children brings happiness and without these things you must be miserable. This is the burden of the recent two biopics Austen (Becoming Jane and Miss Austen Regrets); that she preferred not to marry what was available to her, did not want the pregnancies, genuinely enjoyed her life writing and studying all the time and had no regrets is just not allowed. Bluestockings are disliked because they present themselves as not needing men or children to the public imagination and so they’re presented as ugly and sexless (many New Yorker cartoons show reading girls in this light) and lonely and sour.

I’m talking about reprisals, people getting back at the women who thinks God knows who she is, and who take her stance to be an affront to their shaky self-esteem.

By the middle of the 19th century women did manage to publish their own work (though it was still common for a woman’s work not to be published until years after her death and then in a censored form or reframed) so you do get more achievers and higher achievement and get yet more today, but it’s still risky and dangerous in the teen years which are crucial for later development.

But it was and still is very hard when in most publications (the exceptions are those meant for women, managed by women) are 80 to 90% men. There is far less expectation the woman will write greatly. Low expectations are not only presented for the woman’s self, but what are the possibilities she’ll get her work published and if published treated with respect. It will be women’s poetry, a woman’s novel, a woman’s film. These are phrases which are derogatory in and of themselves, putting these works in their place. Mini-series films (very great, intelligent works of art) well they’re soap operas meant for women.

You can really see the difference in women’s writing in individual cases once you see the woman has real expectations not only that she will get published, but that she will perhaps make money (and so perhaps achieve a modicum of independence) and that her work will be treated with respect, not derision, indifference, or just as bad the over-praise, the condescending overpraise. (Trollope who was no feminist insists women’s writing should be overpraised). So we get the incomparable Aphra, the matchless Orinda, the (whatever double-edged superlative you want) Emily. What’s really astonishing about Emily Dickinson is she did write so greatly and have no where to publish, no expectation of money or independence, or respected reviews and admiration, and no certainty her work would not lay in the boxes for a long time and then be lost.

One must also bring up that still today women are encouraged and taught to be submissive, docile, and not aggressive. It’s not becoming. And it takes practice to know how, so in previous centuries where women didn’t go out, they didn’t know how to do it in a diplomatic or acceptable way.

So if I were to talk about women’s poetry I would bring out the problem of low expectations and the envy and resentment and reprisals women face when they want to spend a life writing poetry. Never mind areas of the world where the woman’s very life is threatened if she sits down and writes. The supposed inclination of women for diaries, journals, letter writing comes not just from the circumstances of women’s life (living at home in private) but that here is an area where if you had a room or space of your own and a drawer and pen and paper or today a computer you can do it, especially at night or in the early morning. Lots of women who were writers have written all the night through or in the early morning before the family she finds herself in get up.

The first article in the most recent issue of the WRofB by Lori Rotskoff takes on the articles in the _New York Times which proclaimed how young women who went to expensive prestigious colleges in large numbers are supposedly opting out because they decide to. Rotskoff says first of all it’s not large numbers, and then she goes on to talk of the difficulty of having a family and spending the enormous time and energy that’s demanded in the workplace if you want advancement. What she cannot get herself quite to say is it is easier to stay home, if you have a husband or partner who earns enough and is a decent person to live with. The article like most takes on the values of ambition as a given, the possibility of success as not in and of itself suspect and to be punished except in the reverse way of (rightly) criticizing people like Linda Hirshman who apparently (I’ve only read her online article not her book whose title would prevent me from buying it fullstop, Get to Work)

berates women who decide to stay home.

I don’t use the word choose. It’s loaded. It presumes far more options and choices and freedom than the word decision. Even decision is too emphatic because most decisions are not thought through but erupt. There’s a wonderful line at the top of p 18 (the poetry page! of the periodical): “We sometimes have to make our lives from what’s left to us, not from what we wanted.”

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 16, 7:07am # - A little more to Clare who did respond to me on WWTTA:

Now that I’m awake I’d like to say to Clare’s that perhaps music escapes gendering to a certain extent because it is so abstract. While since the 19th century we are taught to align this kind of music with this story or that picture, I’m usually not persuaded that this passage of music means I should imagine happy peasants. It’s true music has deep moods which we align with moods we can describe with words, but more than most art it is free of necessary association. The abstract visual arts try for this, but for my part I like realistic looking paintings, sculptures and beautiful (I know this is a problematic word but let it go) landscapes.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 16, 7:11am #

commenting closed for this article