Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

a woman's "novel" to be getting on with · 11 April 08

Dear Marianne,

A line in one of Fleur Adcock’s poems stayed with me immediately upon reading it: Adcock says that when she’s at home or travelling, she has “quite enough friends to be going on with …”

So I thought I’d frame my latest list of books read through and enjoyed immensely with the thought they were for me an equivalent of near Adcock’s wry line: “enough to be getting on with.”

There’s a certain kind of woman’s book I find that is the equivalent of an intimate supportive woman friend. They are not easy to spot since the advertising for books, and particularly women’s books, is often so misleading, indeed downright lies (as in the first copy of Mansfield Park I ever read whose blurb called it a “rollicking comedy”). I found this last fall with Rosamond Lehman’s The Weather in the Streets and The Echoing Grove and Nicola Beauman’s book on women’s fiction in Britain from the 1920s to 40s. I crave this kind of book; it need not be fiction, can be in verse, but it often reads like a novel; I seek it out and when I find it, revel in it for the time it lasts.

Since February books of this type I’ve found & read, with some commentary:

Jane Smiley’s Ordinary Love and Good Will

Iris Origo’s Wal in Val d’Orcia: An Italian War Diary, 1943-44

Margaret Forster’s Hidden Lives: A Family Memoir

Leah Schwartz’s the life of a woman who managed to keep painting

Good Will is an ironic title. Smiley’s he narrator created an enclosed world he expected his wife to live with him in, one which excluded outsiders. He was very cruel to the son, and I was glad at the end to find that my feeling the stance was ironic (we were not to see the narrator as he sees himself) was correct.

Val D’Orcia is an account of war (in this case in northern Italy in the Tuscan countryside and in Rome) from the point of view of someone who is not an actor of violence. She gives birth in Rome during the time. She has taken in some 24 children extra. She talks of the countless thousands of displaced children across Europe as she details this part of her life and the children, older relatives (mothers too). She can only be a victim or act to help others—from starvation, homelessness, losing all sane perspective and other results of war. She is also an “in” person and very sophisticated so when she listens to the radio, reads the newspapers, or talks to other people (often upper class or “in” and knowing) she can present a persuasive truthful account of what’s happening.

There is remarkably little cant in this book. What she has to tell ought to shock—though it doesn’t me, at least not quite. She tells of the deliberate bombing, continual and massive of civilians and how the Allied men machine-gunned down women, children, any male civilians, young or old, in many places and continually. She tells of the reactions of the survivors to these horrific incidents: resentment and fear and a kind of determination to try to survive as best you can. The people bombed do not fall over in a desire to cave in: this is known and she brings out how this comes about: anyone who can bomb you from the air and then massively murder you is not someone you are eager to surrender to. Those who have brought this war upon you are not your friends either; they don’t care about you except as you serve their purposes.So she talks about shifts in party alliances.

Really this could be a book about what happened in Iraq where a

village or town called Fallujah was massively destroyed in hideous

retaliations, thousands murdered and bombed. And then what was the result among Iraqi people. That is, War in Val d’Orcia has general application.

Forster’s is about her grandmother, mother and aunt’s and her young life. There’s too much to tell so I’ll just remark one phase of her mother’s life reminded me of Alan Bennet’s heroine in Bed Among Lentils. After a couple of decades married to a man much her inferior in intelligence and depth of feeling, one she gave up a well-paying job for, who demanded she live on his small salary, be a domestic slave to him and what children he wanted to inflict on her, she met a vicar who she felt she could have loved, and had a nervous breakdown.

One of the happiest and exulting experiences I had while at Portland, Oregon, was when I sat staring at Leah Schwartz’s thick book about her life filled with glorious reproductions of her art. The Arlington Club at Portland, Oregon, had a library downstairs, and seemed to have equipped each room with a small select library itself. We had about half a book case on a quarter of one wall filled with books, mostly good ones, well-picked to be varied, and interesting. It reminded me of Landmark places this way.

When I got home, I ordered myself a copy of Schwartz’s book. It came in the mail last week and I have since reread and reperused it. Looking on the Net, I find there’s hardly anything about her life. No wonder really: she came from a strong socialist background, led an unconventional life with her parents as a girl, her early years were independent, difficult & unconventional, and she has maintained her strongly progressive politics and feminism until today—all the while being a doctor’s wife (luckily he makes money and he also does publish papers on cancer) and mother of two sons (and a third from a first marriage, brought up by someone else). The tone of her book is inspiring without being at all pretentious or schmaltzy.

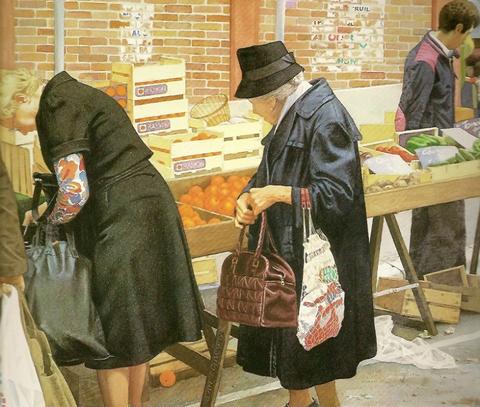

Her pictures of the real world around us, its real streets, herself, her family, friends, real people as we see them (with kindness and generosity, compassion):

Dijon Market

Still life arrangements & lovely flowers, womanly forms:

Orchid

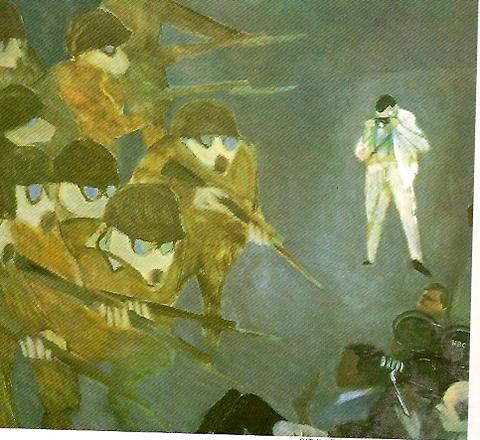

Strong political satire from a leftist and radical point of view, feminist, often cartoony and grim:

Sit in Demonstrations

Iyllic watercolors of places she’s travelled to:

Oxford

and lived and worked in:

Mill Valley Kitchen

There was an article last week in the Sunday Observer (April 6, 2008) about how Virago imprint has changed the landscape of reading available (to women especially), celebrating Persephone books, and this month the Women’s Review of Books was just filled with insightful reviews giving me information about women’s lives and books found nowhere else.

Now not all women’s books have this quality of lived life and offered deep companionship I seek, and some men’s books do (e.g., Henry James and Trollope do frequently; Paul Scott; Orphan Pamuk does [_Snow]); some prize marketplace niches aim at such books (Booker Prize, Whitbread, not American prizes so much which is interesting to me as I often don’t like American books any where near the way I can an English, UK, Canada, French or Italian or hyphenated-colonial type one).

I read women’s poetry for the same reasons I love the above kind of women’s books.

Another Westminster Bridge

by Alice Oswald

go and glimpse the lovely inattentive water

discarding the gaze of many a bored street walker

where the weather trespasses into strip-lit offices

through tiny windows into tiny thoughts and authorities

and the soft beseeching tapping of typewriters

take hold of a breath-width instant, stare

at water which is already elsewhere

in a scrapwork of flashes and glittery flutters

and regular waves of apparently motionless motion

under the teetering structures of administration

where a million shut-away eyes glance once

restlessly at the river’s ruts and glints

count five, then wander swiftly

away over the stone wing-bone of the city.

Jeannette Winterson says Oswald’s poem is in part a response to Wordsworth’s poem.

Elinor

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I’m glad you liked Hidden Lives – I thought it was excellent and brought out the sorts of secrets that many families have, as my sister has been discovering while delving into family history. I was especially moved by the life of Forster’s mother.

Her Precious Lives is also good, about her sister-in-law’s terminal illness and her father’s old age, looking at topics which are too often skated over or ignored.

I remember liking Jane Smiley’s Ordinary Love and Good Will very much, although I don’t have the details of the book in my mind now as it was a few years ago that I read it – I had a Smiley phase where I read as many of her books as I could get my hands on. I especially liked her historical novel Lidie Newton (don’t remember the full title now). I do agree that it is good to find a book where the author feels like a friend – I think for me this is often the case with 19th-century novels because the narrator’s voice tends to seem as if it is talking to me while I read.

— Judy Apr 12, 4:55am # - Dear Judy,

Thank you very much for this useful response. Yes what I look for is citations of titles of such books, and advice on which book by a woman author I’ve liked to read next.

In her book, A Very Great Profession: The Woman's Novel, 1914-39, Nicola Beauman argued it's common for women to read novels as voices talking to them in a conversation they can't have elsewhere or rarely do (except among intimate friends); that women have understood they were doing this from Austen's time on; only in the later 19th century did it become sufficiently understood to be articulated. Carol Gilligan's The Psychology of Women presents the psychological argument: women want and need other women as intimate friends for a support network. In Hidden Lives, Forster shows us the tragedy of an ordinary woman's life in our society. Her mother, Lily, had some gifts, and they were stifled utterly; she turns to her sisters in later life for letters to read. We see her feeble efforts to try to suppress her daughter. The grandmother was a silent heroine who created enough wealth to give the daughters a decent childhood and herself; she was also lucky in the man she married, luckier than any of her daughters.

I never finished Smiley’s history of the novels (13 something-or-others, a magaziny title), but did find a insightful critical acumen in it. It was Kathy who recommended these two titles to me to begin with. I'd like to read more and will get the historical novel you recommend.

Kathy Curtin offblog told me about Karen Joy Fowler’s new Wit’s End, I’ve bought myself Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, and Diana told me about Justine Piccardie’s Daphne. I so loved Fowler's Sister Noon and like DuMaurier at any rate. So I'll try another sequel.

I’ve not finished it as yet so I didn’t cite it, but another sharp and powerful book by a woman of the type we’re citing is Caroline Kettlewell’s Skin Games. By telling with rapid and quirky insight truths about her family life, she makes us understand how she came to wound herself continually with a razor, was for a while anorexic (self-mutiliation or inflicting pain on oneself go with anorexia). She conveys a lot by suggestive stark dramatic scenes.

As you know, Bobbie Ann Mason is an American woman writer, somewhat southern, who seems to speak to me.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 12, 8:47am # - Come to think of it there is a similar gain in a woman’s film—only not quite, it seems they have to be more heavily ironic or undercut what they present by comedy because it’s public space and so jeering from other people (especially macho male types) in this social situation (even in the dark theatre it’s social) is a continual possibility they have somehow to check.

E.M.

— Elinor Apr 12, 10:19am # - Now of course I’m wondering if I’ve recommended the right Smiley! I loved The All-true Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton, because it is a historical novel told in the first person, something which pulled me in, and set during the American Civil War – but I also remember liking A Thousand Acres, a modern version of ‘King Lear’, very much, and Moo, which is set in a college, so might have a particular appeal for you… maybe you could look at the reviews at Amazon and see which one appeals the most.

I couldn’t get anywhere with one about estate agents (Good Faith, I think it was called) and gave up on it.

— Judy Apr 12, 4:56pm # - I had sent to WW and to Kathy C, the following article which is about women’s books too:

“Hard Times

At the New York Times Book Review, all the misogyny is fit to print Written by Sarah Seltzer

http://bitchmagazine.org/article/hard-times

The New York Times Book Review has never exactly embraced passionate advocacyunless it was promoting Pynchon’s and DeLillo’s place in the postmodernist canon. Even worse, it has become the place where serious feminist books come to die or more accurately, to be dismissed with the flick of a well-manicured postfeminist wrist ..."

Kathy replied:

“I agree with much of what Seltzer says. I had noticed fewer women were being mentioned in the NYT Best of lists in Dec. Hadn’t noticed the number of women’s books reviewed or the space given to them. On the other hand I have noticed fewer “celeb-written” reviews, which may mean that reviews are actually fairer: academics and bibliophiles , who can presumably express an opinion without offending a friend or dissing a publisher, more often review nowadays (unless this has changed since last year, when I was reading the review regularly). I’m sure someone is keeping stats: obviously that was a big gaffe not to mention a woman in the top 10 fiction.

It’s necessary to sift through the detritus of any of these reviews. Joanna Kavenna's Inglorious, which the NYT Reviewer considered mediocre and dull (when is a novel about depression NOT dull), is on the Orange Prize long list. I. of course, liked the book, knowing that it would interest me despite the reviewer’s opinion. So that reviewer sold me a novel she didn’t like.

but, yes, it is often women dissing women.”

To which I said:

I wonder if without thinking it through the type of woman hired and promoted is precisely the sort who would not like woman’s books, who would prefer action/adventure and male type books, perhaps with a female hero in the center, say a detective story with a female hero (LeCarre’s Little Drummer Girl). The woman’s reviews that are liked and approved are those that get published and she is given more things to do as she pleases more, and so she tailors her thoughts yet more. I’ve found in reviewing in academic publications, this kind of thing happens all the time. It’s not narrow politics, but a sort of feeling the editor has he likes what you write, or something in it he doesn’t like.

It’s usually a he; hardly ever a she.

So even when the powers that be in charge of any publication don’t deliberately hire a known woman anti-feminist (that is the type making money from doing this—and there are a number of them), they still hire and promote someone who does not offend them. They don’t want to hear anything negative about men as a group; that’s male-hating. And they are not interested in female lives. I remember a man who came to the blog and said how everything in The Jane Austen Book Club was boring except the opening. The opening was a fast-moving satire on small humiliations in public in modern life.

In any case I agree that in general one must sift through reviews. I would say it’s not true to say that academic reviews are free from politics. It’s that the politics is personal: they are aware that this particular small clique in academia publicly thinks X about a given author or book and that this clique has invested part of their career (say a published paper) in backing this view, so if they go against it, they will be going against this clique. This really controls academics. It’s not quite as direct as popular publishing and trading favors and positive reviews between people who are making money from writing reviews and books.

Thank you for telling me of Inglorious. Now surely that is just the type of book the “old boys” network would despise and find dull. John Carey is not depressed; he despises depressed people (and loathes Virginia Woolf so we can see what he'd think of women's books of the 20th century as she has been so influential); John Gross (another admired critic in the public better periodicals) likes action-thrust in his reading and has said so; what the point of a book without proper closure?

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 13, 8:47am # - From Francoise on WW:

“Sans possibilité de bouger et d’avoir accès à mon ordinateur, j’ai lu, un peu forcée, des livres dits “reposants”, prétés par des amis. Et j’ai lu des volumes de “chick lit”, autres que Bridget Jones’ Diary. Il y a beaucoup d’idioties dans ce type de littérature. Cependant, si elle connaît une telle vogue, c’est qu’elle répond à une aspiration des lectrices. Je penche pour l’”escapism”, comme les contes de fées, le roman populaire, le roman feuilleton, le roman à sensation, le roman policier de l’âge d’or britannique, les romans historiques – un peu au-dessus des Mills and Boon et Barbara Cartland. Je me demande aussi quelle est leur filiation. Viennent-ils de certains romans légers (Angela Thirkell, EM Delafield, Mrs Minniver) pour femmes que nous avons vus avec Nicola Beauman ou Christine Jordis? Pourquoi n’y a-t-il pas d’équivalent en France? Est-ce une étiquette post-féministe?

A toutes ces questions et à d’autres, auriez-vous des réponses ou des indications, Ellen? J’ai regardé nos archives de juillet/août 2007 dans lesquelles vous parliez de Bridget Jones. Je n’ai pas de précision particulière. Une idée?”

— Elinor Apr 14, 1:46am #

commenting closed for this article