Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

"Quite enough books to be going on with ..." · 25 June 08

Dear Friends,

Another blog on books I recently read straight through and enjoyed thoroughly. This list resembles my November letter, for the books are diverse in type, era, and by men as well as women. I put them in order of last finished:

Stella Tillyard’s Citzen Lord: The Life of Edward Fitzgerald, Irish Revolutionary (biography)

Christa Wolf’s Cassandra (includes two travel narratives, her working diary, and a meditation on the significance of the main character)

Margaret Forster’s Precious Lives (memoir of her father and aunt)

I read as part of my projects towards writing and with friends on listservs, and liked more moderately

Glenda Hudson’s Sibling Love and Incest in Jane Austen’s Fiction (literary criticism)

George Etherege’s The Man of Mode (Restoration comedy)

Anthony Trollope’s Eustace Diamonds (novel)

And listened to Donada Peters’ delightful reading of an unabridged text of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford.

Christa Wolf’s Cassandra is such a masterpiece, so important for this century and for in particular for women readers to read, I need to make a separate blog on it when I finish writing postings on it (to Women Writers through the Ages at Yahoo); I’ll write about Glenda Hudson’s book when I write here about the proposal I’m going to send to JASNA to do a paper next October 2009 (working title: “Disquieting Patterns in Austen’s Novels”); I’ve gone on about Cranford before, and write on Eustace Diamonds every time I write about the Palliser films (from 5:10-7:14), so that leaves three books to tell something of.

******************

1) In Citizen Lord Tillyard is a very rare writer in the west nowadays to present as a hero, and someone to admire thoroughly a man who deliberately goes about to foment rebellion. In most books he would be presented as some kind of horror or devil: Edward Fitzgerald actively organized people to rebel and fight; he went about proselytizing and worked hard to set up groups of men ready to go to war to overthrow the British government and landowners (of which he was a son of one of

the richest and most powerful) in Ireland. He was what is negatively today termed an “agitator.” He was a continual active agitator for violent revolution to kick out the English and also depossess the few wealthy Protestant (and any Catholic) landlords in Ireland.

The only 20th century novel I know of which also makes a hero of an “agitator” determined to change the order by whatever means necessary is John Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle. I remember how shocked my students were when they read a book that made a hero of such a man. “In dubious battle” could be a good subtitle for this book—only Fitzgerald did not think the battle dubious because his goal was not.

How do you throw over cruel regimes which are determined ruthlessly and forcibly with money and arms on their side to repress and kill anyone who will change the order?

Tillyard shows how Thomas Moore’s life of Fitzgerald (which has been the one which has stereotyped the man), romantic depiction of Fitzgerald as an idealist and chivalrous is utterly inadequate: he recognized that the establishment would not give up its power and wealth without violence overthrow. Where he was wrong was this belief he and others have had that the generality of desperate people will rise and you can make them into an effective army. This has been a repeated delusion (1745 in Scotland, 1916 in Ireland). He did very well understand the violence he would unleash by beginning such a civil war.

She presents Fitzgerald’s idealistic social philosophy and how he was again and again excluded and kicked out of parliament, and how gradually he found himself isolated from the powerful of his country as one after another of his friends said he was gonig too far for them.

A particularly insightful part of her portrait is her allowing the reader to see that Fitzgerald’s dislike of society, his sensitiveness, and (if you will) his misanthropy. He was really a disciple of Rousseau, a serious one. It’s hard to get at this for he wrote little of his bitterness and despair and sense of alienation; you have to see this from his actions. His family would of course save his idealistic assertions, and his kindness and affectionate nature. We have to look at what he did and read against the grain or subtly to see how much he disdained the materialism, the hierarchies, just about everything that comes with social man in the ancien regime (and again in other forms today). So to say, how astonishing such the younger son of a wealthy man and powerful should give all up to fight this way. But to him he didn’t give all up; he didn’t want that all at all. He had a strong distaste for what was on offer. So why not cultivate his own garden in retirement. His nature and now we have ideals didn’t permit that; he would get depressed. Odd to say but he became an agitator to fend off depression. He really reacted strongly against injustice and cruelties of every day life.

We see this is in his close intimate continual companionship with the ex-slave black man, Tony Small. He was very close with a young ex-slave, a black man named Tony who after Tony saved Fitzgerald’s life in a battle in the US became in effect the closest human being to Edward Fitzgerald there was. They were hardly apart and Tony couldn’t write (perhaps couldn’t read though there are signs he could some) so not much has survived; however, Tillyard manages to give us a sense of this man and his relationship with Fitzgerald. The togetherness of the two men until near the end of Edward Fitzgerald’s life (just before he was shot and arrested, when he did leave Small behind, perhaps knowing this would be the end of his life) reminds me of how Teresa Guicciolo’s brother stayed with Byron through thick and thin while the two were in Greece together. With Small though, Fitzgerald found himself in a relationship utterly apart from the crass cliques, materialism, and performative communities of his milieu.

Fitzgerald commissioned a lovely picture of Tony Small, by John Roberts, in 1786.

The portrait (like the one Fitzgerald had done of himself shortly

before the end, for his family, and by Hugh Douglas Hamilton) does simply take over the conventions of heroizing and idealizing of the era. It’s a rococo imaged landscape. What is different is the lack of militarism, lack of violence, the sweetness and melancholy and distanced look in Tony’s face. He looks highly intelligent. To picture Tony thus was another radical egalitarian act.

Fitzgerald’s marriage to Pamela “Sims,” daughter of the Duke d’Orleans, Philippe Egalite (guillotined) and Felicite de Genlis was the result of his having fallen in love with Elizabeth Sheridan, and having had a deeply emotional liaison with her. Sheridan treated Elizabeth badly and himself had affairs and she wanted some happiness. She became pregnant by Fitzgerald and gave birth toa daughter by him, but died shortly afterwards of TB and too many pregnancies. Pamela looked like Elizabeth and to marry her was a statement of radicalness too. They lived a far more Rousseauian existence than Rousseau ever did—and kept and attempted to bring up their children.

The famous 1798 revolt and attempted invasion of Ireland was by the way hopelessly bungled. The French did come, a huge fleet (to take over themselves) but storms, a lack of insight (the United Irishmen waited until the French were to land so when the few French who got there came they saw no support), not decent technology, and failure of nerve made half the fleet lost at sea and the other half turn around the go back to Brest. To have them land in a superhidden place was counterproductive though understandable as the British and Irish establishment in the persons of their leaders and effective military were ruthless and brutal in the extreme, killing, and beating and burning and destroying people house-by-house as they took back arms.

Yvette tells me Patrick O’Brien’s The Commodore includes a retelling of the 1798 rebellion: Stephen Maturin is said to have been “out” with Fitzpatrick and Wolf Tone (about whom I know very little so will put on our list some stuff this coming week), but foresaw how hopeless the enterprise was and was against violence. As Tillyard shows, O’Brian’s portrait is that of Thomas Moore which is (I suppose like his of Byron) suggests that Fitzgerald was somehow child-like. Nothing could be further from the truth. O’Brian’s Maturin is onto something: Edward Fitzgerald was committing a form of self-destruction, knowingly. And for me it’s this aspect of Fitzgerald, his Rousseauist rejection of the outrageous norms of society at the heart of his revolutionary fervor that makes him most interesting, and is Tillyard’s original insight.

If you read Tillyard’s book you will for once really get a feel for genuine liberal thought and what it means and also the ambiguousness of what really meaning to change an order involves. Reading it made me want to reread her Aristocrats, a book built out of the letters and private papers of the famous four Lennox sisters, one of whom, Emily, was Fitzgerald’s mother, with whom he maintained a close loving relationship all his life. She had 24 childen, married the childen’s tutor after having been his mistress for many years. I now also would like to rewatch the film adaptation, Aristocrats another chance.

******************

2) Margaret Forster’s Precious Lives is a powerful book about dying: how people die as seen in the lives of two relatives close to Forster. As the book opened, I felt she was idealizing a man she had disliked and showed had blighted her mother’s life in Hidden Lives, but as the book progressed and he begins to move near daeth, she becomes honest about her dislike of him, even how she wishes he were dead (partly because of the burden, but also partly because she begins to respect his intense stubbornness and insistence on living a life true to himself to the end, his sheer authenticity; at the close she finds it wrong and odd to keep a life going when the person knows nothing but physical misery and meaninglessness, loneliness). Part of her gift seems to be the ability to dwell on pragmatic and practical details of existence and make them yield private and general meaning.

Like her Hidden Lives, her story of her aunt’s decades-long struggle with cancer and life history is about the ironic waste of a woman’s existence, remarkable courage amid twisted choices first driven by social norms (the aunt married when she was lesbian) and at last finding herself. Precious Lives is really a book worth reading. And especially for women because it’s often women who become the caretakers of the aged.

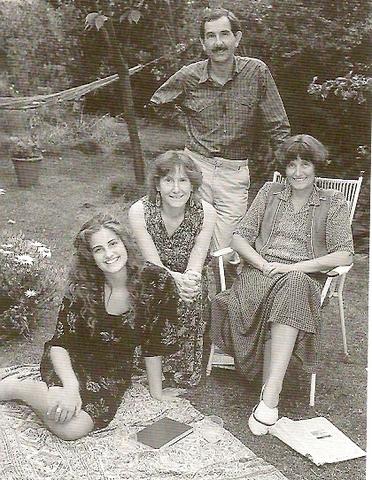

Marion, Margaret’s aunt, center stage, with Margaret sitting on chair

I find myself able to read Margaret Forster’s books at any time of day no matter how tired I am. I bought a novel which Angela Richardson recommended to me some time ago—Keeping the World Away (it’s about Gwyneth Johns, the painter)—I’ve that on my TBR pile of a woman’s book to be getting on.

After I posted about Precious Lives on Women Writers, Judy G. wrote to the listserv:

“I’m glad to hear Ellen liked Margaret Forster’s Precious Lives, since I was also impressed by it – it seemed to me that it addressed a lot of questions which are usually ignored about the painful process of growing old and ill, and it struck a chord with me because of the experiences of some of my own relations. I thought it was all the more poignant because she does show just how awkward and infuriating she often found her father, and yet how this takes nothing away from his suffering.

The book has stuck in my mind because it does address that difficult reality of illness and death which is so often skated over

I agree that I also find Margaret Forster extremely readable, at any hour of the day or night.:)”

Farideh Hasanzadeh thanked me for “sharing [my] spiritual experiences” and suggested that

“Jane Kenyon’s ‘Reading Aloud to my Father’ when he was dying is extremely powerful:”

I chose the book haphazard

from the shelf, but with Nabokov’s first

sentence I knew it wasn’t the thing

to read to a dying man:

The cradle rocks above an abyss, it began,

and common sense tells us that our existence

is but a brief crack of light

between two eternities of darkness.

The words disturbed both of us immediately,

and I stopped. With music it was the same

Chopin’s Piano Concerto—he asked me

to turn it off. He ceased eating, and drank

little, while the tumors briskly appropriated

what was left of him.

But to return to the cradle rocking. I think

Nabokov had it wrong. This is the abyss.

That’s why babies howl at birth,

and why the dying so often reach

for something only they can apprehend.

At the end they don’t want their hands

to be under the covers, and if you should put

your hand on theirs in a tentative gesture

of solidarity, they’ll pull the hand free;

and you must honor that desire,

and let them pull it free.

“In this poem Jane can convey the pain of dying man to the reader very honestly. I translated it behind the waters of my eyes. One of interesting points in this poem for me is the end line.”

Of Forster’s memoir, she said:

“I don’t know why writers and directors ignore the painful and terrible and ugly moments of old age and death. In films and novels we see a very beautiful poetic face of death

I bring back the immediate context: at the close of Forster’s memoir, she describes her father’s last couple of years. He was 96 and falling apart physically, most of the time in a state of misery from physical ailments or his own exacerbated isolated sensibility (sensibility may seem an odd word for this as the old man was continually hard and harsh to everyone he spoke to, a lifetime habit, but I think it appropriate), yet everyone conspired to keep him alive—the nursing home, the medical staff, she and her siblings (no matter how conflicted and she relieved when he died). She asks the question why and offers the idea this comes from a mistaken or unexamined idea about life’s value as well as fear (for ourselves). So the last line of Kenyon’s poem in this context can mean the man should have been allowed to “pull” his hand “free.”

******************

3) George Etherege’s The Man of Mode (first performed 1676) is one of the plays we are reading on Eighteenth Century Worlds at Yahoo. I found this to be a superior play. I attribute its memorable power to Etherege’s having endowed the character of Dorimant with psychological reality; it seemed to me Etherege poured an idealized version of himself into Dorimant, and the character emerged as believable.

The characters formed different groups. One surrounded Dorimant presented as a cool gallant rake centrally: His disillusion and boredom with his longtime aging mistress Mrs Loveitt manifested in scenes of hypocrisy, high quarrelling, irrational jealousy (on both their parts) and were effective, partly because I didn’t expect the playwright to give the woman any burden or depth of humanity and he did. Dorimant says at one point why he cannot bear Mrs Loveitt anymore is that “in my absence kindly listening to the impertinences of every fashionable

fool that talks to you.” That’s interesting that this bothers him.

Bellinda giving herself to Dorimant for a night (and at last someone actually did have transgressive sex during the course of the play) was moving because Dorimant just did it for the fuck and wished her away again, all the while she wanted him to love her, and yet cared more that no one should know. After it’s over (the night together):

Bellinda: “Can you be so unkind to ask me? [he asks why is

she sighing?] Well—were I to do it again …

Dorimant. “We should do it, should we not.”

For the sex and it seems she agrees.

The third person who formed this triumvirate was Sir Fopling Flutter. Like the fops in the plays thus far he is introduced rather late, and the opening scene seeks to ridicule him and the actor is expected to ham it up, but he too became interesting when he quarrelled like a real person with Mrs Loveitt over his own mortification at being ridiculed.

Fear of social life was a central motif in this strongly social play.

A second group were the Bellairs, where young Bellair is going to be coerced into marriage for money and escapes by marrying Emilia who is also under terrific pressure to marry for money someone she doesn’t care for, an older man. Lady Townley, Bellinda’s confidant (in effect) unites the Dorimant group with the Bellair group as she is aunt to young Bellair. One of their scenes reminded me of Henry Tilney making fun of social life’s conventions (Act III, scene i, where Bellair and Harriet play at absurd social gestures and body language, “Your head a little more on one side. Ease yourself on your left left and play with your right hand …”)

The final group is Lady Woodville and Harriet. Harriet is the girl

who has come up to town to escape the monotony and nothingness of existence in a restrained hypocritical domineered over environment in the country. We are expected to think she’s pretty and she is very witty (as witty as Austen’s Elizabeth) but for me the one unbelievable element in the play is Dorimant apparently falls sufficiently in love with her and she with him that we are to imagine they will try to marry eventually. The play does not end in their marriage, but her return ot the country. He does not reform in any real way. This is part of its strength.

A second level of the play is the brilliance of the utterances of the

characters. It reminded me of Pride and Prejudice only the sayings were much more disillusioned and franker. They are to the point today still. They were like axioms by LaRochefoucauld.

Emilia: Our love is frail as is our life and full as little

in our power; and are you sure you shall outlive this day?

Young Bellair. I am not; but when we are in prefect health, ‘twere an idle thing to fright ourselves with the thoughts of sudden death.

Dorimant to Mrs Loveitt: “You mistake the use of fools;

they are designed for properties and not for friends.

Some were funny in a deeply cynical way: Dorimant had quite a number of these: “I believe nothing can corrupt her but a husband.” He is coolly cruel often and laughs at the women who go for him, especially n the scenes with Lady Loveitt but more quietly with the bawd (orange lady). He gives away details that sound like real life: on gambling, “The deep play is now in private houses.”

The continual disillusions reminded me of Dryden’s Marriage a La Mode, only they were more general and more believable, not strained at presentation, but continual and pervasive. This is a grown up person’s play. I remember somewhere reading that though this play is occasionally revived, it’s nowhere as often as its quality would predict. Congreve’s characters in The Way of the World are more famous and therefore preferred, and perhaps they are not as thoroughly witty. Like Congreve, Etherege introduces his character slowly. Almost one at a time per scene, and they are still appearing in the third act. This helps us individualize them.

The types found here are also used by Austen in her novels, and as I read the play I felt as I’ve felt before a good deal of her strength comes from her imitations of plays. Old Bellair really reminded me of Austen’s Sir John Middleton in S&S. one of the witty male characters makes fun of social conventions by parodying it in front of a heroine and how she joins in: this is Tilney and Catherine Morland in the assembly at Bath.

To conclude, Man of Mode is a libertine play, basically amoral and Dorimant in life would be a man cruel to women; nonetheless, I found the play charming and satisfying. Charming because of the style and appercues (pithy sayings) and satisfying for the same reason: I feel the sayings capture truths about human nature and the characters while types believable enough. I like the way they parody life stylishly or while holding up their heads. Mrs Loveitt is a victim, but she would victimize others. On the other hand, I see nothing to like or admire in Dorimant himself, and, like Catherine Trotter (a poet and playwright of the later 17th century), I find it disquieting that most who have read or seen the play who have gotten a chance to write about it, are not bothered by this man as a hero. She wrote of this play that in it “Deceit’s a jest, false vows are gallantry” and for the sake of women she’d have “ev’ry Dorimant appear a knave.” Presumably, Samuel Richardson agreed, for though he delighted in Harriet and for Grandison took over the type for his Harriet Byron; for Clarissa, he took admiration for Dorimant as central to his Lovelace.

Early in the film, far more playfully than the novel, Lovelace (Sean Bean) hides a letter in the Harlowe garden (1991 BBC Clarissa)

Clary (Saskia Wickham) and Anna Howe (Hermione Norris) obligingly find said letter

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Farideh adds this note from Donald Hall, Kenyon’s husband:

"Jane wrote many poems about her father ’s illness and death, of which ‘Reading Aloud to My Father ’ is the latest and last. Reuel Kenyon died of cancer in Michigan in 1981; Jane and I stayed with him for much of his illness, helping Jane’s mother care for him. When Jane was dying I thought of this poem. Music was her passion,as it was her father’s; at the end, she could not bear to hear it, because it tied her to what she had to leave. In her last 24 hours,her hands remained outside the bedclothes, lightly clenched. I touched them from time to time, but I didn’t try to hold tight.”

— Elinor Jun 25, 11:25pm # - PS. on Tillyard’s book and subject: she also describes Wolf Tone who committed suicide literally, Edward Fitzgerald was committing a form of self-destruction too, knowingly.

Anthony Trollope would have known a great deal about this incident -- he knows an enormous amount about Ireland and politics, and would have read Thomas Moore's life. I surmize he would have seen Moore's life to be the idealistic and naive account it is. He would not have been in sympathy with it, as he was not in symnpathy with Byron.

E.M.

— Elinor Jun 25, 11:31pm # - As the blog is already long enough, I place Judy’s thoughtful posting on Man of Mode here:

"Hello Ellen and everyone, I’ve now read this one and caught up on the postings about it here – I enjoyed the play and especially liked the scene you mention, where the young people behave as if they were courting, and convince onlookers they are having a conversation very different from the witty comments they are actually exchanging. I like your comparison with Henry and Catherine in Northanger Abbey.

I was interested to see it stated in the footnotes to the edition I read (the Penguin English Library Three Restoration Comedies, edited by Gamini Salgado) that the character of Dorimant was based on John Wilmot, earl of Rochester, who was a friend of Etherege’s and is ‘said to have been very fond of quoting from Waller.’ I mainly know about Rochester from the portrayal of him as a tortured figure in the film The Libertine, starring Johnny Depp, but this gives a more lighthearted view – one difference being that in the play Dorimant’s disease is fake, whereas in The Libertine Rochester’s terminal VD is all too real.

I’ll quote a bit from Salgado’s introduction:

‘All Etherege’s plays are good, but The Man of Mode is undoubtedly his masterpiece. Its chief merit consists in the uncompromising realism with which it investigates the implications of Restoration libertinism. When we first meet the hero, Dorimant, he has just cast off one mistress and is about to take on another. He has no scruples about faking a jealous rage in order to get rid of Mrs Loveit, nor has his new lady love Belinda any about aiding and abetting him. There is no reason why this process of changing mistresses should not go on for ever, in which case the play would deserve Professor Knights’ condemnation for demonstrating nothing ‘except the physical stamina of Dorimant’. In face it demonstrates a great deal more, for it deals with teh education of Dorimant from what Mr John Wain has aptly called ‘the fighter-pilot’s mentality’ (he must get them before they get him) to a genuine regard for another person (Harriet) which must overcome a great deal of vanity and ill-will before he can acknowledge it even to himself.’

I find this interesting and agree that most of Dorimant’s relationships seem to be battles, but I’m not so convinced by his regard for Harriet, which seems to be convenient for the plot, enabling a happy ending, but not to fit in with everything else we’ve seen of his character!

Salgado doesn’t think this libertine is banished from London forever at the end of the play, commenting: ‘His final exile to the country is to be understood as a strictly temporary penitence, much like the year of visiting the sick in hospital to which Rosaline sentences the young nobleman of Navarre in Love’s Labour’s Lost. London has already been established in the play as the only possible centre of civilised existence.’

All the best,

Judy”

— Elinor Jun 25, 11:48pm # - And Nick wrote:

“Thanks for the quotes from Salgado. But I am afraid I don’t see ‘uncompromising realism’ – as you point out the truth of Rochester is that he died young in a very unpleasant way. Indeed my own reading of Rochester is that much of his behaviour is to be seen as self-medication for persistent and deep-seated melancholy. But that’s probably a tangent.

Like you I am wholly unconvinced by the notion that Dorimant really changes at the end of the play.

I do find The Man of Mode cruel. I definitely dislike this most of the plays which I have read. Dorimant revels in cruelty and Harriet joins in with him. Deborah PayneFisk describes their pairing as…

‘the consummate libertine union, a mating of leopards’

which I think puts it very nicely. Their behaviour is rewarded

and congratulated.

The cruelty is especially reserved for Mrs Loveit who infact is the most moral person in the play. When Dorimant ask her to publically humiliate Fopling she replies…

‘I will not, to save you from a thousand racks, do a shamelessthing to please your vanity’.

Her morality and her love for Dorimant are made to appear absurd. The former may be slightly so but I see no reason to question the latter. Here is her closing dialogue…

>>Mrs Loveit: There’s nothing but falsehood and impertinence in this

world! All men are villains or fools: take example from my misfortunes. Bellinda, if thou woulds’t be happy, give thyself up wholly to goodness.

Harriet (to Mrs Loveit) Mr Dorimant has been your God almighty

long enough. ‘Tis time to think of another.

Mrs Loveit: Jeered by her! I will lock myself in my house and never see the world again.

Harriet: A nunnery is the more fashionable place for such a retreat and has been the fatal consequence of many a belle passion.

Mrs Loveit: Hold heart till I get home! Should I answer, ‘twould make her triumph greater.

Mrs Loveit then leaves - she is cast out, excluded from the various contrived happy endings. Now one way of reading all this is to admire Harriet - a 'strong young woman' as Brewer claims (co-incidence I just read this! :)). She plays the libertine - Dorimant - at his own game and wins. She remains witty, independent, unattached in any deep sense. There is never any real suggestion that she and Dorimant love each other, however strong their mutual physical and intellectual admiration for each other may be. Love, 'passion' is for the dopes and dupes.

Now I understand that this can be argued the other way. That precisely because Harriet proves herself Dorimant's match in intellect and indeed in verbal cruelty she is therefore to be applauded. But I would argue that she does this by an accommodation to, a compromise with, libertine values. And in Etherege it seems to me that those values take on a particular cruelty. In Wycherley on the other hand (in The Country Wife anyway) the only losers are self-important men - the cruellest man in the play is made the biggest fool of. Wycherley certainly does not endorse libertine values in the way Etherege appears to (because I do not read Horner as a straightforward hero) : as previously discussed his position appears to me deeply ambiguous and all moralities are rejected. The endings are significantly different - it is hard in my view to read the ending of The Country Wife as in any way 'happy', whereas that of The Man of Mode certainly is - at least for those characters who have not been excluded from it.

Nick."

— Elinor Jun 25, 11:51pm # - For another portrait of a former slave, this time in a position of authority: Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley, by Girodet.

http://blog.catherinedelors.com/2008/06/13/citizen-jeanbaptiste-belley-beyond-a-portrait.aspx

— Catherine Delors Jun 26, 11:48am #

commenting closed for this article