Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Mary Chandler, poet & Bath milliner (1687-1745) · 7 July 08

Gentle friends,

Mrs Penelope Clay (Mary Stockley)’s hat seen from the Bath, filmed in a modern day shop in Bath (‘95 BBC Persuasion)

Since Ms Place (aka Vic) chose to frame my posting on Anne Home Hunter (1742-1821), as a songwriter, poet, and wife, contemporary of Jane Austen on her Jane Austen’s World, I’ve been thinking I should again make an effort to put little essays about the life and writing of women poets and painters on this blog. And today Ms Place posted on one of the real life stories from Stella Tillyard’s Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox (1740-1832), which remarkable book we are reading and discussing on Eighteenth Century Worlds At Yahoo (after which we’ll watch and discuss the 6 part film adaptation by Harriet O’Carroll). So I feel a need to emulate her!

I had been putting poems and lives of poets from the 16th through early 20th century here on this blog a couple of years ago (you can reach them by clicking on “poetry” as a subject); then I started being more consistent in writing one every Friday most Fridays of the year for 2 years now, sending them all to Wompo. Occasionally I again put one here or a poem or picture. But basically I put them all on Wompo. Now I want to return to putting some here, and to do this more often than before for a while, partly to help myself towards choosing the 30 women I am supposed to cover during the November Wompo online festival of women poets.

I’m in a better mood today than I have been because I sent a letter to the JASNA committee where I corrected my error in my recent proposal to JASNA of a a paper on siblings in Austen for the 2009 meeting in Philadelphia (“Disquieting Patterns in Austen”). Also Kathy liked the proposal, and Diana thought my c.v. in my cover letter was strongly impressive. So I’m encouraged again. If any of my friends reading this blog would like to see the proposal, just email me here or offblog, and I’d be delighted to send you the 3 page attachment. If you would then send me wild screams of praise, how appreciative I’d be.

In the meantime here is a life and writing of the mid-28th century English poet and Bath milliner (whence the still from the 1995 Persuasion of Mrs Clay’s hat from the back), Mary Chandler (1687-1745). She was a milliner and it’s said starved to death when she put herself under the control of a doctor; but we don’t have to believe that. She wrote wonderful comic and moving poems.

An (idealized) urban street by Antonio Canaletto (mid-18th century), one such as Mary Chandler could have worked in

I begin with her most often reprinted comic poem and end with her touching poem to friendship. It’s the latter poem that made me choose her tonight, for I have been thinking about how much all my friends mean to me.

A True Tale

To Mrs. J-S.

Written at her Request

Why, Madam, must I tell this idle tale?

You want to laugh. Then do so, if you will.

Thus take it, as it was, the best I can;

And laugh at me, but not my little man:

For he was very good, and clean, and civil,

And, though his taste was odd, you own not evil.

ou know one loves an apple, one an onion;

One man’s a Papist, one is a Socinian:

We differ in our taste, as in opinion.

Not often reason guides us; more, caprice,

Or accident, or fancy: so in this.

His person pleased, and honest was his fame;

Tis true there was no music in his name,

But, had I changed for A the letter U,

It would sound grand, and musically too,

And would have made a figure. At my shop

I saw him first, and thought he’d eat me up.

I stared, and wondered who this man could be,

So full of complaisance, and all to me:

But when he’d bought his gloves, and said his say,

He made his civil scrape, and went away.

I never dreamed I e’er should see him more,

Glad when he turned his back, and shut the door.

But when his wond’rous message he declared,

I never in my life was half so scared!

Fourscore long miles, to buy a crooked wife!

Old too! I thought the oddest thing in life;

And said, ‘Sir, you’re in jest, and very free;

But, pray, how came you, Sir, to think of me?’

This civil answer I’ll suppose was true:

‘That he had both our happiness in view.

He sought me as one formed to make a friend,

To help life glide more smoothly near its end,

To aid his virtue, and direct his purse,

For he was much too well to want a nurse.’

He made no high-flown compliment but this:

‘He thought to’ve found my person more amiss.

No fortune hoped; and,’ which is stranger yet,

‘Expected to have bought me off in debt!

And offered me my Wish, which he had read,

For ‘twas my Wish that put me in his head.’

Far distant from my thoughts a husband, when

Those simple lines dropped, honest, from my pen.

Much more, he spake, but I have half forgot:

I went to bed, but could not sleep a jot.

A thing so unexpected, and so new!

Of so great consequence—So generous too!

I own it made me pause for half that night:

Then waked, and soon recovered from my fright;

Resolved, and put an end to the affair:

So great a change, thus late, I could not bear;

And answered thus: ‘No, good Sir, for my life,

I cannot now obey, nor be a wife.

At fifty-four, when hoary age has shed

Its winter’s snow, and whitened o’er my head,

Love is a language foreign to my tongue:

I could have learned it once, when I was young,

But now quite other things my wish employs:

Peace, liberty, and sun, to gild my days.

I dare not put to sea so near my home,

Nor want a gale to waft me to my tomb.

The smoke of Hymen’s lamp may cloud the skies

And adverse winds from different quarters rise.

I want no heaps of gold; I hate all dress,

And equipage. The cow provides my mess.

‘Tis true, a chariot’s a convenient thing;

But then perhaps, Sir, you may hold the string.

I’d rather walk alone my own slow pace,

Than drive with six, unless I choose the place.

Imprisoned in a coach, I should repine:

The chaise I hire, I drive and call it mine.

And, when I will, I ramble, or retire

To my own room, own bed, my garden, fire;

Take up my book, or trifle with my pen;

And, when I’m weary, lay them down again:

No questions asked; no master in the spleen

I would not change my state to be a queen.

***********

Mary Chandler (1687-1745) was one of a growing number of women poets of the 18th century who were working women, not pseudo-gentry, not gentlewomen. It’s usually put (and was at the time) that because she was badly crippled or deformed, she did not marry but instead opened a milliner’s shop in Bath (nearby the Pump Room where Elizabeth Montagu and her friends, in history called the Bluestockings would sometimes meet). From Chandler’s poems she seems not unhappy (a number of friendship poems of great warmth), and the most famous is her long comic (and successful) “Description of Bath.”

Royal Theatre, Bath mid-18th century

However, it’s also said (we all remember what Virgil said about Rumor) that under the “care” of George Cheyne (famous physician who recommended dieting and exercise), she became anorexic (a girl who wanted “out”or was continually made to feel her body was unacceptable). Let us hope not, but we may say it doesn’t sound likely that a woman who had stayed in business successfully for 35 years would starve herself to death. Her epitaph (18th century poets would write their own ironic epitaphs) does harp again on her looks. It does not begin with her life and success but rather “Here lies a true maid, deformed and old …” Is not it terrible a woman should endlessly judge herself as an object a man might want to go to bed with? Like the comic Horatian “True Tale,” her epitaph does have a combination of wry self-acceptance and stalwart Horatian ideals of being content with what you can manage to wrest from life: “Her book and her pen had her moments of leisure”.

An essay by David Shuttleton, “All Passion Extinguish’d: The Case of Mary Chandler (1687-1745)” (in Isobel Armstrong and Virginia Blain’s Women’s Poetry in the Enlightenment: The Making of a Canon, 1730-1820 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1998) makes what happened to Mary more understandable. Shuttleton says she was endlessly put before other people as a kind of freak and made to feel her so-called “ugliness.” What felt like a half-pretense excuse for writing also registers how people really saw her. She did put herself under the “care” of George Cheyne and grew very thin. It might be she died of natural causes. There was (as ever) a spiteful mocking rhetoric thrown at Cheyne’s healthy diets and exercises, and there does seem to be some evidence (scary) that in fact Cheyne did cooperate with people who wanted to control and punish or shape a daughter into some absurd ideal (one letter from another woman describes a treatment she got in a sanitarium which sounds like the worst I’ve read about what went on in Bruno Bettelheim’s clinics). Happily Chandler did not leave her shop to follow doctor’s orders :)

As you can see from her “True Tale,” Mary also refused offers of

marriage later in life. Her poetry was published by Samuel Richardson and seems to have had some fulfilling relationships

with congenial people through her writing.

I conclude with a friendship poem I just read by her:

A Poem on Friendship. Written in 1729. [from The Description of Bath (1736)]

Friendship! the heav’nly Theme I sing;

Source of the truest Joy;

From Sense such Pleasures never spring,

Still new, that never cloy.

‘Tis sacred Friendship gilds our Days,

And smooths Life’s ruffled Stream:

Uniting Joys will Joys increase,

And sharing lessen Pain.

‘Tis pure as the etherial Flame,

That lights the Lamps above;

Pure, as the Infant’s Thought, from Blame;

Or, as his Mother’s Love.

From kind Benevolence it flows,

And rises on Esteem.

‘Tis false Pretence, that Int’rest shews,

And fleeting as a Dream.

The Wretch, to Sense and Self confin’d,

Knows not the dear Delight;

For gen’rous Friendship wings the Mind,

To reach an Angel’s Height.

Amidst the Crowd each Kindred Mind,

True Worth superior spies:

Tho’ hid, the modest Veil behind,

From less discerning Eyes.

From whose Discourse Instruction flows,

But Satire dares not wound.

Their guiltless Voice no Flatt’ry knows,

But scorns delusive Sound.

While Truth divine inspires each Tongue,

The Soul bright Knowledge gains.

Such Adam ask’d, and Gabriel sung,

In heav’nly Milton’s Strains.

Such the Companions of your Hours,

And such your lov’d Employ;

Who would indulge your noblest Pow’rs,

But know no guilty Joy.

And thus as swift-wing’d Time brings on

Death, nearer to our View;

Tun’d to sweet Harmony our Souls,

We take a short Adieu.

Till the last Trump’s delightful Sound

Shall wake our sleeping Clay;

Then swift, to find our Fellow-souls,

As Light, we haste away.

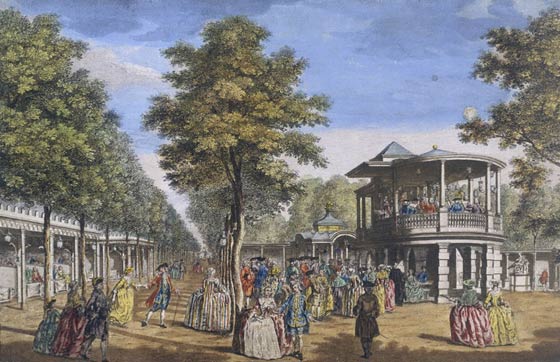

Vauxhall Gardens, pleasure gardens in London, Johann Sebastian Muller (1751 print)

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article