Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_The Duchess_ was a writing and reading girl too · 19 September 08

Joshua Reynolds, Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (1774)

Dear Friends,

I just read Diana Birchall’s blog on her (frustrating?) interview with Amanda Foreman (“Debriefing the Duchess”), and was most amused by the quotation from Emma: “I was pleased with my own perseverance in asking questions, and amused to think how little information I obtained.” (Emma)

We had quite a thread on Amanda Foreman’s book, originally titled Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, on Eighteenth Century Worlds at Yahoo; it was prompted by Foreman’s published responses to the new costume drama said to be adapted from her book, The Duchess. The film stars the latest sexualized anorexia icon, Keira Knightley, and sensitive addition to the brotherly-male helper archetype-actors, Ralph Fiennes (director, Saul Dibb, writers, Jeffrey Hatcher, Anders Thomas Jenson—all men).

What happened was Foreman came out publicly with a sort of back-handed repudiation of her interpretation of Georgiana’s complex character in her excellent book. Foreman’s book shows a varied complicated woman coerced into an unhappy marriage, and looking for independence and real role in the public world. Foreman’s commentary since the movie present an alternative view which is reductive and against the facts as she showed them to be: Foreman is backing the movie which replaces a complex woman with a romance novel: Keira Knightley has become an icon for frail, abject love-starved women, and now Foreman would have us believe Spencer’s melancholy was the result of her having been deprived of one of her children because it was illegitimate.

On Foreman’s own account, Georgiana had many children and was a better mother to them than her mother had been to her; and shows little grief over the child she was not allowed to bring up (though the Duke could keep his illegimate children and mistress, her companion in her house); her grief came more from what she was driven to do by her debts (see The Sylph). The movie distorts Spencer’s relationship with Charles Grey: he was an incident in her life; the relationship that mattered (as told by Betty Rizzo in her brilliant Companions Without Vows) was with Elizabeth Foster, Spencer’s paid companion and her husband the Duke’s mistress and second wife (by whom he had children too).

Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807), Lady Elizabeth Foster (ca. 1785)

Or, if you prefer,

Joshua Foster, Lady Bess Foster (1788)

We got into quite a discussion of this: people said Foreman was doing what other writers sometimes do: supporting a movie for which she has been paid an ample fee and may get much more. Catherine D on Eighteenth Century Worlds said Antonia Frazer has done the same thing.

Foreman had also published a maudlin account of one of her pregnancies: she had a very bad version of a condition not uncommon: the fetus is allergic to toxic compounds in the gravid woman or her diet and causes such nausea the pregnant women is in danger of dying; it is not uncommon to abort in the 5th montn. Atul Gawande has an excellent essay on this condition (nausea during pregnancy so bad it’s life-threatening); if anyone is interested, it’s in his Complications. She now has 5 children of her own, but not to worry as she is wealthy without movie dividends (married to a banker, the daughter of a famous screenplay writer accused of communism).

Saul Dibbs’s (to name just the director) movie omitted other central aspects of Georgiana Spencer Cavendish’s character, e.g., her genuinely liberal politics. Also Georgiana’s addiction to gambling—alongside her great friend, the radical wealthy politician, Charles James Fox. And she was a reading and writing girl. In Foreman’s book, Foreman says she first became attracted to Georgiana as a subject because she wrote such wonderful letters.

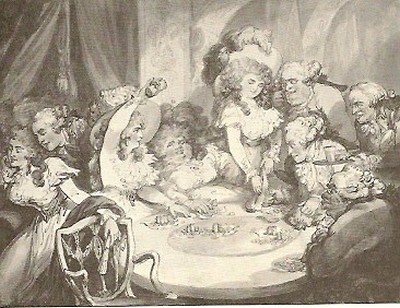

A gaming table at Devonshire House by T. Rowlandson (Georgiana throws the dice; her sister, Harriet, takes money from her purse; Charles James Fox and the Prince of Wales are seen)

Thus, my blog today is dedicated to showing that in a minor way Georgiana Spencer Cavendish is another of my foremother poets. I did write such a posting to Wompo on her a few weeks ago.

So, in the manner of my foremother poet postings to Wompo (women poets listserv), Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (1757-1806) wrote poems throughout her life (mostly light social verse), many many letters and one novel (probably autobiographical), The Sylph.

Here is Lady Georgiana’s one well-known poem prefaced by an impressionist painting of snow:

Fanny Churberg (1845-1892), Winter Landscape (1880)

The Passage of the Mountain of St. Gothard.

To my Children

Ye plains, where threefold harvests press the ground,

Ye climes, where genial gales incessant swell,

Where Art and Nature shed profusely round

Their rival wonders—Italy, farewell!

Still may thy year in fullest splendour shine!

Its icy darts in vain may Winter throw!

To thee a parent, sister, I consign,

And winged with health, I woo thy gales to blow.

Yet pleased Helvetia’s rugged brows I see,

And through their craggy steeps delighted roam;

Pleased with a people, honest, brave, and free,

Whilst every step conducts me nearer home.

I wander where Tesino madly flows,

From cliff to cliff in foaming eddies tossed;

On the rude mountain’s barren breast he rose,

In Po’s broad wave now hurries to be lost.

His shores neat huts and verdant pastures fill,

And hills where woods of pine the storm defy;

While, scorning vegetation, higher still

Rise the bare rocks, coeval with the sky.

Upon his banks a favoured spot I found,

Where shade and beauty tempted to repose:

Within a grove, by mountains circled round,

By rocks o’erhung, my rustic seat I chose.

Advancing thence, by gentle pace and slow,

Unconscious of the way my footsteps pressed,

Sudden, supported by the hills below,

St. Gothard’s summits rose above the rest.

Midst towering cliffs, and tracts of endless cold,

The industrious path pervades the rugged stone,

And seems—Helvetia! let thy toils be told

A granite girdle o’er the mountain thrown.

No haunt of man the weary traveller greets,

No vegetation smiles upon the moor,

Save where the floweret breathes uncultured sweets,

Save where the patient monk receives the poor.

Yet let not these rude paths be coldly traced,

Let not these wilds with listless steps be trod:

Here fragrance scorns not to perfume the waste,

Here charity uplifts the mind to God.

His humble board the holy man prepares,

And simple food and wholesome lore bestows;

Extols the treasures that his mountain bears,

And paints the perils of impending snows.

For whilst bleak Winter numbs with chilling hand,

Where frequent crosses mark the traveller’s fate,

In slow procession moves the merchant band,

And silent treads where tottering ruins wait.

Yet, midst those ridges, midst that drifted snow,

Can Nature deign her wonders to display;

Here Adularia shines with vivid glow,

And gems of chrystal sparkle to the day.

Here, too, the hoary mountain’s brow to grace,

Five silver lakes in tranquil state are seen;

While from their waters many a stream we ‘trace,

That, ‘scaped from bondage, rolls the rocks between.

Hence flows the Reuss to seek her wedded love,

And, with the Rhine, Germanic climes explore;

Her stream I marked, and saw her wildly move

Down the bleak mountain, through her craggy shore.

My weary footsteps hoped for rest in vain,

For steep on steep in rude confusion rose:

At length I paused above a fertile plain,

That promised shelter, and foretold repose;

Fair runs the streamlet o’er the pasture green,

Its margin gay, with flocks and cattle spread;

Embowering trees the peaceful village screen,

And guard from snow each dwelling’s jutting shed.

Sweet vale! whose bosom wastes and cliffs surround,

Let me awhile thy friendly shelter share!

Emblem of life! where some bright hours are found

Amidst the darkest, dreariest years of care.

Delved through the rock, the secret passage bends,

And beauteous horror strikes the dazzled sight;

Beneath the pendent bridge the stream descends

Calm-till it tumbles o’er the frowning height.

We view the fearful pass-we wind along

The path that marks the terrors of our way

Midst beetling rocks, and hanging woods among,

The torrent pours, and breathes its glittering spray.

Weary at length, serener scenes we hail

More cultured groves o’ershade the grassy meads;

The neat though wooden hamlets deck the vale,

And Altorf’s spires recall heroic deeds.

But though no more amidst those scenes I roam,

My fancy long each image shall retain

The flock returning to its welcome home,

And the wild carol of the cow-herd’s strain.

Lucernia’s lake its glassy surface shows,

Whilst Nature’s varied beauties deck its side;

Her rocks and woods its narrow waves enclose,

And there its spreading bosom opens wide.

And hail the chapel! hail the platform wild!

Where Tell directed the avenging dart,

With well-strung arm, that first preserved his child,

Then winged the arrow to the tyrant’s heart.

Across the lake, and deep embowered in wood,

Behold another hallowed chapel stand,

Where three Swiss heroes lawless force withstood,

And stamped the freedom of their native land.

Their liberty required no rites uncouth,

No blood demanded, and no slaves enchained;

Her rule was gentle, and her voice was truth,

By social order formed, by laws restrained.

We quit the lake-and cultivation’s toil,

With Nature’s charms combined, adorns the way;

And well-earned wealth improves the ready soil,

And simple manners still maintain their sway.

Farewell, Helvetia! from whose lofty breast

Proud Alps arise, and copious rivers flow;

Where, source of streams, eternal glaciers rest,

And peaceful Science gilds the plain below.

Oft on thy rocks the wondering eye shall gaze,

Thy valleys oft the raptured bosom seekk

There, Nature’s hand her boldest work displays,

Here, bliss domestic beams on every cheek.

Hope of my life! dear children of my heart!

That anxious heart, to each fond feeling true,

To you still pants each pleasure to impart,

And more—O transport!-reach its home and you.

(1799)

Joshua Reynolds, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, with her daughter, Lady Georgiana Cavendish [“Little G”] (1783)

**************

There’s an excellent essay on Georgiana’s poem by Elizabeth Fay (I found this on a Scottish Romantic Women writers site, interestingly).

To which I can add: like many women poets’ poems, it is sentimental, personal; a species of life-writing (though not confessional to use the terms canvassed recently here). Spencer has bought into the cult which idolized Switzerland, partly an outgrowth of primitivism and nationalism, which led to the sentimentalization of Scotland as a romantic place; partly the result of their revolt—see background by Fay). It’s a curious cult, because if you read about the real politics of this small state, you will not discover much liberty—and I believe it’s only recently women got the vote. There were groups of highly cultvated people living in Switzerland who lived what we might call an Enlightenment life, among them Stael, Gibbon, and (my Jane Austen-related research and reading interest) Isabelle de Montolieu. Georgiana would have visited these, and been charmed like Byron and the Shelleys were before her. And Rousseau came from there. I suppose that’s enough to account for some of it. Frankenstein is partly set in Switzerland.

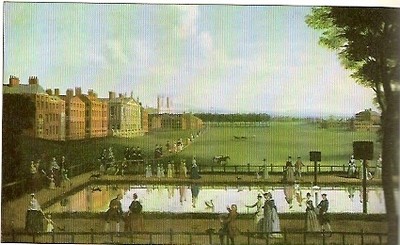

Idealized view of Green Park, English school, a view Georgiana would have had from Devonshire House

The poem has of course been mocked, a sort of backhanded tribute. I say of course because Spencer became a target of very cruel public abuse (like Dora Jordan, the famous actress at the time, mistress of a man who became king and inflicted at least 11 children on her and then dumped her in the end). Some of this was her high rank and association with the high mighty, more that she dared to get into public life, campaign and work openly for causes, hers were radical. She was a great friend of Charles James Fox. They did like gambling into the wee hours together.

To return to Georgiana’s life: for a general popular accent, Wikipedia provides names, facts, dates. Like the movie, the article omits Georgiana found much time to be a reading girl and then reading woman, and wrote a considerable amount (autobiographic), thus paving the way for two good books, one not as well known as it should be: one of the 8 or so chapters of Betty Rizzo’s excellent Companions without Vows, she tells the lives and analyzes the relationship of Georgiana Spencer Cavendish and Elizabeth Foster.

The outlines of Rizzo’s and Foreman’s book are the same: early pressured marriage, cold indifferent husband, many pregnancies, gambling for release, then the companion, Elizabeth Foster (a beauty as seen in the above portraits at the time) who became Spencer’s best friend, and lover too (so Foreman hints and Rizzo agrees) and the Duke’s mistress (and gave birth to his children too). Rizzo and Foreman show that Elizabeth Foster also became the person Spencer leaned upon. Spencer needed someone for emotional support and never got it until she met Forster; she was a loving mother and gave strong support to her children partly the result of her memories of deprivation. Forster though also took advantage of this, and become in some ways the leader of the menage a trois: shows what a personality can do.

Rizzo sees Spencer’s relationship with Charles James Fox (who we encounter as a gambler and idealist radical politician in Stella Tillyard’s Aristocrats—a book similar to Foreman’s also made into a movie) not only a political alliance but another emotional dependency. The two of them in the wee hours of the morning gambling. Spencer did fall in love with another male and had at least one child by him; this was a child her husband kept from her, though it was just fine for him to keep his illegitimate children about. There is a record of Spencer’s intense distress over her gambling and what it forced her to do to pay her debts: The Sylph.

After Georgiana’s death, the Duke married Elizabeth.

Rizzo has critiqued Foreman’s book for a sort of false emotionalism. Rizzo also (and here I did agree with her) say that Foreman’s inference at the end that women were not that disabled by circumstances, and deeply engaged in public life was founded on the case of one woman, rich, privileged, and that power behind the throne, contingent, networking was fleeting and ineffective power. The end of Spencer’s politicking brought her nothing and there’s no proof it had any effect beyond causing a great deal of ugly propaganda against here. Foreman herself shows that at the same time Georgiana needed someone to lean upon, she was vigorous and aggressive in political life and was hideously cruelly attacked (really ugly cartoons that are hard to look at).

Foreman’s book is good on Spencer as a intelligent woman, reader, writer, thinking person. She quotes Spencer wonderfully. It’s a shame there is no book of Spencer’s letters or poems. She did at the time attribute The Sylph to Georgiana; then when Betty Rizzo and Lars Troide argued adamently, it could not be by Georgiana, she backed away and said she was not sure. If it wasn’t by Georgiana, it was by someone who knew her life intimately, knew like many another upper class women she was coerced into doing very unpleasant things to pay for her debts: Louise D’Epinay in her autobiographical Montbrillant shows her husband trying to coerce her into having sex with his debtor friend to pay the debt; Maria Edgeworth tells a similar story in her epistolary novel, Leonora. But it seems now that the popular consensus is giving the book back to Georgiana, and an edition has come out attributing it to Georgiana, Foreman changes her mind again. It is a weak novel.

The best of Georgiana Spencer Cavendish is in her letters. And she was a poet.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Diana:

“Dear Ellen, what a gorgeous blog you’ve done – tart, contrarian, with some 18th century asperity. It certainly complements mine! (In a different way than our various pieces complement Vic-and-LA’s pretty sites.) And you’ve skimmed the most ravishing pictures from everywhere, so that you have formed the best dispassionate picture of Georgiana. Foreman does sentimentalize doesn’t she. How well the picture illustrates the poem!

D.”

— Elinor Sep 19, 3:12pm # - From Nancy Mayer:

“Ellen. your blog on Georgiana is interesting. However, there are two points I must make. These are minor and do not affect your point or thrust at all.

One is that Georgiana was not Spencr once she was married. She was never Spencer – Cavendish. In the practice of the day ( and today as far as that goes) she became Georgiana Devonshire. I imagine you did not want to call her The Duchess, despite the fact that it is as correct as your being Mrs.Moody. She should be called Georgiana, the Duchess, or Georgiana Devonshire.Her daughter was lady Georgiana Cavendish before she married.

Also, the picture of her with her child. She only had three legitimate children: Lady Georgiana, Lady Harriet, and Lord Hartinton, who was the marquess of Hartington. I do not know who that Lady Elizabeth Cavendish could be.

Nancy”

— Elinor Sep 19, 4:01pm # - Oops! I mistook; it’s Lady Georgiana, Little G in the painting.

As to the Duchess’s name, I’m not sure what she was called familiarly. Lady Georgiana? if her father had a title? I’d prefer not to refer to her as the Duchess; it seems so pompous and she’s long dead and someone else has the title. The way these names are modernized is to take the last name. But which is appropriate? Spencer or Cavendish? In the case of Anne Kingsmill Finch, after her husband unexpected inherited, she was probably called Lady Anne, though her father was not noble.

Lady Georgiana. But we’ve given this up. It’s not Lady Mary any more but Wortley Montagu.

I don’t think of myself as Mrs Moody at all. Ellen Moody or Ellen is my name. Dr Moody to students. To people who do not know me (such as at a supermarket or store) Mrs Moody is probably the right nomenclature. But otherwise it feels odd to be so called.

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 19, 4:20pm # - I loved this appraisal of Georgina and of Foreman’s book. Interesting to have read it in juxtaposition with Diana’s interview. I love the paintings too. Thanks for sharing it with us.

— Clare Shepherd Sep 19, 4:52pm # - From Nancy:

“Though Georgiana was Lady Georgiana as the daughter of an earl, once she married, she became Georgiana Devonshire. That is her correct name by which she signed letters . That or G. Devonshire when she wasn’t using one of her pet names for herself. Whether or not it feels right, it is incorrect to call her Spencer Cavendish. It would be more correct to just call her Georgiana.

Ellen, you would not make an incorrect citation in one of your academic writings and would take off points if a student called Donne and archbishop and said he was murdered in a cathedral. It is a matter of correctness to call her either the Duchess or Georgiana Devonshire. That is supposing that you do not want to call her ‘Your Grace.’

Nancy.”

— Elinor Sep 20, 9:36am # - But Nancy modern customs trump older ones. I cite Anne Kingsmill Finch, Countess of Winchilsea as Anne Finch. Everyone does. Margaret Lucas Cavendish, Duchess Newcastle is Cavendish. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu is no longer Lady Mary but Wortley Montagu. In peer-edited journals.

I used to call “my Anne” Ann, Countess of Winchilsea but no one today does. She signed her name Ann. I can’t get anyone to use Ann; they say the “e” is the way it’s been done since Myra Reynolds. I know Ann Finch signed herself AW after she was countess (Ann Winchilsea) but I’ve never seen any modern person use it.

I don’t know what is the custom for Georgiana; probably there is no custom as yet as she’s not someone the academic world has been interested in as a writer and poet particularly. Looking at the online essay (on an academic site) which I linked in (by Elizabeth Fay) she opts for Georgiana.

My posting about her as a poet is to try to get people to take serious interest in her. A very good book on her (one chapter of it) is Betty Rizzo’s Companoins Without Vows. Chock-a-block with information. I forget how Betty calls her. It would be interesting to go look. I shall do so tonight.

Ellen

— Elinor Sep 20, 9:37am # - From Nancy:

“That explains much. Thanks for your explanation.

Of course, I am aware that many authors are called by their maiden names even after they marry. I would think it would depend on the name under which they wrote most. If Ann Finch made her reputation under the name Finch, it does make some sort of sense to call her Finch. She herself, as you noted, called her herself Ann Winchilsea, which is correct.

I am surprised that academics would be so sloppy about people’s titles when they would probably object strongly to having their PhD’s ignored.

I did look for her on Google and found that she wrote more than I had thought , so you succeeded in that. Also, as I mentioned, Jane Austen’s song book included the lyrics Georgiana wrote.

Nancy”

— Elinor Sep 20, 9:54am # - Thanks for telling me that Austen had Georgiana’s lyrics in her songbook. I’ll add that to my foremother poet posting for Wompo. I’m glad to know myself. I was much heartened by how many people came over and read my blog. Diana’s had great attention, but I got about 10 to 15 hits over the main part of the day, per hour!

The academic view is really about themselves. I like “Ann Winchilsea” but it’s hopeless. I haven’t any feel for how Georgiana might be renamed (for that’s what they do). I have Rizzo and no time to look now; I will look tonight.

Anne Finch (as she’s called and spelled) made her reputation as Anne, Countess of Winchilsea in 1713 (one book published); as a young woman she was maid of honor at Beatrice’s court (James II) and then she was Colonel Finch’s wife (that’s how she was referred to) or Sister Finch by her sisters. Even then she was not Ann—though that’s how she signs the few remnants of letters we have.

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 20, 9:57am # - From Nancy:

“Devonshire, Georgiana, Duchess of 1757-1806

I have a Silent Sorrow Here

GM7:13, LV031/080

According to GM, this “song from The Stranger. The words by R. B. Sheridan. The air by the Duchess of Devonshire.” In LV, several versions are titled “Favorite Song in the Stranger”. LV031/080 is the version closest to that described in GM (though different key).

http://bama.ua.edu/~jdonley/austen/composers/Dlist.html

This song is called “Silent Sorrow” which goes along with your view of Her Grace.

http://bama.ua.edu/~jdonley/austen/musicpdf/devonshire713.pdf

Nancy"

— Elinor Sep 20, 10:57am # - Dear Ellen,

I thank you for this exceptionally illuminating & thought-provoking piece. It is always especially wonderful for me to read your essays and postings as you always add such splendid art to the writing.

I’ve been busy traveling & working, thus taking a respite from literature, so it is wonderful to catch up on matters cultural through your and Diana’s blogs.

Keep writing! Elissa

— Elissa Schiff Sep 20, 9:14pm # - From Nancy:

“I was wrong, Georgiana wrote music.

The composers whose music Austen admired (Charles Dibdin, well represented in her books, Georgiana Cavendish, the Duchess of Devonshire, whose air accompanies the lyrics of the premier playwright, Richard B. Sheridan, and Stephen Storace, for example) were well-respected and rightfully so, but because not all composed for the orchestra, much of their work has been dismissed.

We would do well to remember that the western canon, of literature or music, had yet to be etched in stone, that comic songs, opera arias, folk ballads and Haydn were frequently on the same program. We have tried to select material that would duplicate the kinds of vocal music with accompaniment heard on the very best of those evenings of music.”

http://juliannebaird.camden.rutgers.edu/JAProgramNotes.htm

Nancy”

— Elinor Sep 21, 7:46am # - Nancy:

“Devonshire, Georgiana, Duchess of 1757-1806

I have a Silent Sorrow Here

According to GM, this “song from The Stranger. The words by R. B. Sheridan.

The air by the Duchess of Devonshire.” In LV, several versions are titled

“Favorite Song in the Stranger”.

LV031/080 is the version closest to that described in GM (though different key).

http://bama.ua.edu/~jdonley/austen/composers/Dlist.html

This song is called “Silent Sorrow” which goes along with your view of Her Grace.

http://bama.ua.edu/~jdonley/austen/musicpdf/devonshire713.pdf

— Elinor Sep 21, 7:47am # - Thank you for the encouragement, Elissa. It’s good to know you’re there. I’m making this one a foremother poet posting for the Wompo festival site, and will do so for a number of later 17th and 18th century poets (up to 1820) and perhaps will give a little circulation on the Net for basically unknown (to any but 18th century scholars and women who study women's poetry) women poets and song-writers!

Nancy, wow. So the Duchess could not only read music, but could write it. All left out of that film. No surprize at that, eh?

Ellen

— Elinor Sep 21, 7:51am # - From a sensible friend:

“I loved both blogs. A non-interview must be very frustrating. Instead of answering with canned comments, it would certainly have been better and easier to for promotion to answer a FEW questions honestly, with a few details. It takes a really creative person to digress from the canned spiel without offending their agents (or whoever). Diana’s questions sounded very reasonable.

I’ve copied the poem, so I can read it at my leisure.”

— Elinor Sep 22, 9:20am # - Yes Diana’s questions were not intrusive or hostile.

Blogs are free: they are not controlled by anyone beyond the writer’s sense, needs, and pocketbook. (That’s one reason they can be so much better than pre-censored edited matter—and worse too of course, but for different reasons and in different ways.) The intelligent thing (and sensible) would have been to ignore what you don’t like as people do reviews. Who complains to a reviewer in a hard copy journal? Only a fool or someone who thinks they can hurt the reviewer. You get nowhere, only expose yourself, for even if you can hurt the reviewer, you are on record (for if you phone, it can also be written down in the blog).

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 22, 12:21pm # - From Kim Roberts:

“I have linked to your blog on my website, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, here:

http://washingtonart.com/beltway/bloglinks.html”

— Elinor Sep 24, 3:27pm #

commenting closed for this article