Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

A review of Abigail Brundin's book on Vittoria Colonna's poetry · 6 October 08

An anonymous little known imaginary image of Vittoria Colonna, from the 16th century, the austere scholar

Dear all,

After all my review of Abigail Brundin’s Vittoria Colonna and the Spiritual Poetics of the Italian Reformation will not be appearing in the Renaissance Quarterly. In a barbed note to me, William Stenhouse rejected it on the grounds RQ prints only “timely” and “brief” reviews of books. My review is no longer than many; the sarcasm about timely refers to the overt feminism of my approach. I was at first asked to cut it savagely; what I did was cut it so as to make it shorter but not change it. My guess is the last two paragraphs were disliked most; and Brundin has friends on the staff.

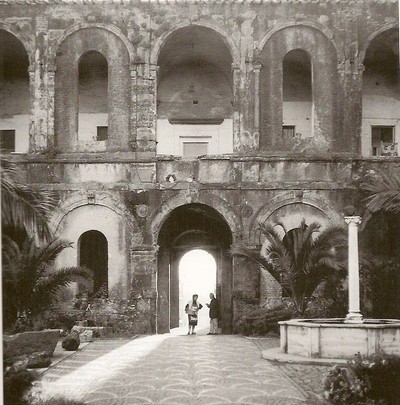

So I have put it on my website: A review of Abigail Brundin’s Vittoria Colonna and the Spiritual Poetics of the Italian Reformation. Perhaps Wompo will put it on their website too – as it’s about a woman poet, Colonna. I’ve added it to my published reviews, and updated my bibliography. The photo below is a modern one which occurs in the catalogue of an exhibition held in Vienna in 1997 of art and texts connected to Colonna:

The Colonna Palace, Rome, old photograph

As I wrote in August, I ruined several days of my time away in New York State this summer reading this book; it reflects the careerism and respect for power politics and networking that have become central to humanities scholarship, particularly (somewhat paradoxically) for early modern women in Italy in the Renaissance. Pompeo Colonna’s treatise on behalf of power for women is not examined ethically (he is for women who manifest masculine traits of the sort that lead to militarism). Nothing is further from the character of the mature Colonna. And of course I was pained by the complete absence of any reference to my translation—while at the same time the attacks on “unhelpful biographism” struck me as aimed at my site and approach. Reading this book actually caused me to wake at night with nightmares; happily I can no longer remember what they were.

I did catch up on the latest studies and also now know that the manuscript of poems published by Toscano consists of an exquisite choice of the most beautiful of Colonna’s erotic poems. had I had that available to me when I was making my arrangement for my book, I probably would have followed that ordering in part. I’ve done peer reviewing & editing of articles for RQ as well as The Sixteenth-Century Journal), and it takes a long tedious time and is irritating—mostly because of the jargon used in the writing and the attitudes of the people.

The Renaissance scholars are often yet more exclusionary than either the 19th or 18th century scholars and more conservative politically. Not all by any means, e.g., Arthur Kinney of English Literary Renaissance; but I remember the one conference I went to where except during one lunch no one, not a soul spoke to me. The strong tendency to set themselves apart and above others might stem from the self-flattery that helps one to spend huge amounts of time reading religious and guardedly obscure texts in libraries; also the mindset of the powerful people studied is so awful—unashamed thugs most of the men and defensive repression characterizes most of the women (the latter defended by today’s women scholars), all very much pre-Enlightenment; though this is not true of Vittoria Colonna, most of them would have despised Shakespeare, looked down on Michelangelo; perhaps such attitudes rub off. One must wait until the 17th century to find genuine rebellion written down, for the 18th century for the bold attempt to shift human consciousness to a people-centered humane view of the world and life.

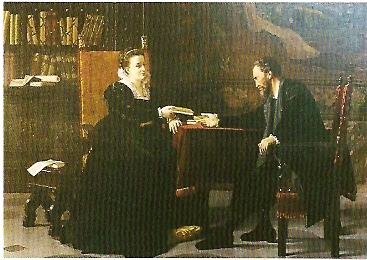

Another idealized portrait of Colonna, here with Michelangelo as a congenial literary friend, 1853, by Francesco Jacovacci (1838-1908)

It’s a good thing I had no contact with the academic elite who make their handsome living and live their privileged existences off this material when I did my translations. I might not have gone through with them. They are still to me a matter of great pride and joy—even though publishing them has brought me much pain or trouble and vexation, not in the readers who come to my site (and sometimes contact me), but in some of my encounters with these salaried and prestigious professors: in the case of my review of Zarri’s splendid book about letters by early modern Italian women, after publishing another review by one of his graduate students, another editor (whose name I, alas forget) made a composite of those I had sent him (probably reflecting his own intrigues and agenda) without my permission and published it in The Sixteenth Century Journal. I felt a certain amusement at how hard he must’ve worked to produce this composite; he had to have sat down with three different versions and reworked the paragraphs to some extent, all the while moving my transitional sentences around.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From a member of EighteenthCentury Worlds:

“Fascinating review. Great last paragraph. I hope it will be printed in some form in RQ.”

— Elinor Oct 6, 7:50am # - IN response to the person on ECW:

Thank you.

It’s hard to say. On previous occasions I was led to believe what I wrote would never be published, and it was—but in a different and semi-censored (through generalizing) form. What was happening was I was being pressured to change my text without the editor admitting this.

Yes the last paragraphs are those that are nowadays unacceptable to conservatives and people who want to erase feminine values and their place in a woman’s canon & women’s writing.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 6, 7:52am # - I’ve had a note (I was asked not to put it on the blog) from someone who had a similar experience at RQ recently. She says she then offered her review of the book to another journal, a 17th century one, where it was accepted. She thanked me for exposing “the situation.”

I didn’t think I was unusual. I've experienced all sorts of politics in writing reviews for periodicals over the years. I admit though I never thought to send the review to another periodical which might want to have a review of the particular book.

I’ve been gratified, for all day long every ten minutes or so my blog has been read; I’ve not kept a log of the website where the review is, but I suppose those who came to the blog looked at the review. I probably got more readership today than I would have in RQ. Certainly more attention even if no one ever quotes my review in a peer-edited journal.

The Wompo Festival has now accepted the review, so it'll be part of that November festival

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 7, 12:14pm # - From Nick:

“Just read your blog – very sorry to hear about it, Ellen – what a really horrible experience. But I am delighted your other papers have been accepted.”

— Elinor Oct 8, 7:08am #

commenting closed for this article