Date: Sat, 13 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin -- The Readjustment

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Judy wrote:

I find the story in itself quite slight but interesting - and will look forward to finding out more about Austin.

I just finished The Readjustment myself. It is a strange piece. Should be an entertaining discussion.

Dagny

Date: Thu, 11 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Essay on women's supernatural fiction

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

As usual with me, while looking for one thing on the web, I've come across something completely different! I was looking to see if I could find any essays or discussions on 'The Lady's Maid's Bell' - I didn't manage to find any, but did come across an interesting feminist essay about women's supernatural fiction. This is "Two Centuries of Women's Supernatural Stories" by Jessica Amanda Salmonson, which was first published as the introduction to the anthology 'What Did Miss Darrington See?: Feminist Supernatural Stories (New York: The Feminist Press, 1989).' She has since revised it a bit and includes some "afterthoughts" at the end, mainly on 'Restless Spirits', where it's clear she has a dispute with Lundie, saying she pinched her research - although at the same time she says it is an excellent anthology.

Here's the link: http://www.violetbooks.com/womens-supernatural.html All the best, Judy

Re: Jessica Salmonson's "Two Centuries of Women's Supernatural Stories"

Date: Fri, 12 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Essay on women's supernatural fiction

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Like Judy I recommend Jessica Amanda Salmonson's introduction to What Did Miss Darrington See?. I came across it quite a while ago (when we were reading ghost stories on Trollope-l). Salmonson shows there has been a suppression of women's writing, indeed the suppression of the dominant figures in a genre which itself lends itself to what Didier defined as Ecriture-Femme (as well as several other people who have written about characteristics of women's literature most famously Gubar and Gilbert).

There is a problem though: Salmonson does not discuss the content of these stories nor does she say what is meant by "conservative" as opposed to "X" writers. I use the "X" because she doesn't even have an opposing term. But this is important, for not only has the woman's point of view been suppresed, and lines of tradition coming out of women's fiction (as in the case of "Mother Radcliffe" and a projection of a sado-masochistic female sexuality still operating in Byatt's Possession), but there has really been an attempt to use the conservative readings of these texts as the way to understand them as well as the masculinist one. The conservative is a religious point of view: we saw that in the way Oliphant's story is presented unless you go a deeper into the scholarship.

A rare good or frank book on this (which however deals just with male's fiction) is Jack Sullivan's Elegant Nightmares where he argues that modern ghost stories are a popular equivalent of Kafka's vision crossed by radical-secular modernist thought (why all the references to science are there). I'm still waiting to get _Perils of the Night_ said to be a feminist study of gothics and ghost. My library (Fenwick) never bought this one -- it's "not general" enough I was told. Universal has re-become male. It was superexpensive on the Net (the way Patrick Wright's anti-heritage books are), but at long last I came across an old copy which came inexpensively. The longer studies do when they are good go into content and what the story says to us. Unless you make the ideological explicit -- bring them out of the closet -- it exists only in oblique camouflage and does its work on readers unconsciously or not at all.

I am puzzled why a woman like this doesn't bring out the content of subversive women's supernatural fiction squarely.

The question remains then, how do great women's stories of the supernatural differ from great men's ghost stories of the supernatural? Rereading Salmonson I realized it was reading Catharine Lundie's introductory essay and then beginning to go through her anthology, Restless Spirits -- in which I read "The Readjustment" -- that has made me aware of one important difference: in women's stories of the supernatural the ghost is often the site where the woman author can be found.

The ghost is the woman author, is her alter ego. In men's stories, the ghost is the enemy, not the self. Some fearful malign thing, not him at all.

As I wrote earlier today the woman's ghost contains in her the woman author's own grief, loss, rage, revenge. I hadn't seen that because I hadn't read enough ghost stories by women in a row and ones which are feminist in thrust (ideology counts). This insight doesn't help that much with "The Lady's Maid's Bell" but it does with Mary Austin's "Readjustment" which I read last night. It's another very short one.

Ellen

Date: Sat, 13 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin, "The Readjustment"

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Well, Ellen was right--sometimes the ghost is the author's presence, and it couldn't be more true than in "The Readjustment," in which Mary Austin's personal frustrations with her marriage are twisted into a ghost story, where the widower husband is forced to admit that it was all his fault, and the women (living and dead) agree that "common" men are just incapable of much more than such a pitiful admission.

This story is slight, but gains meaning with a knowledge of Austin's biography: She was the unhappy wife, like Emma Jeffries, sure that she was better than her husband and their neighbors, unable to accept with much ease any expressions of concern about her only child, who was severely disabled and very difficult to manage (unlike the boy child in this story, Mary had a daughter, and did not have a sister to come "take the child away with her"--instead the girl was institutionalized at age 11, at Mary's expense, in a small private hospital in Santa Clara CA). When we hear in this story that "the intensity of her wordless struuggle against [the affliction of her crippled child] had caught the attention of the townspeople and held it in a shocked curious awe," that was Mary Austin's experience too. Even after her death, the people in one California town where she lived refused to permit a monument to her, recalling Austin as a miserable person who disdained them all.

And her husband Wallace Austin was like Sim Jeffries--a mild quiet man, who enjoyed living in the remote Owens Valley and didn't much enjoy working any one job for long. Wallace, like Sim, didn't want to talk about the child, nor about his wife's ambitions, nor about where they might better live to have more success as a couple. Wallace didn't want to sign the commitment papers when Ruth Austin was placed in the hospital--but he didn't propose any alternatives, either. Mary blamed Wallace for the rest of her life for their daughter's disability--she believed he was hiding something about his family history, a "tainted inheritance" that she would never have perpetuated, had she known. When Sim finally sees the Jeffries' child as "the advertisement of his incompetence," he's admitting something Wallace Austin probably never did, but something Mary Austin firmly believed.

The story also gains from its original context: after appearing in Harper's Magazine in April 1908, it was part of Austin's 1909 collection of short stories, Lost Borders, in which the stories are all set in the same remote region, far from the ordinary expectations of Anglo culture. So, there are ghosts, and unconventional couplings, and fateful encounters, and righteous prostitutes, and curses... all introduced by a story/essay called "The Land," in which Austin explains that these are stories that don't fit into polite dinner party life, because they're too earthy and unbelievable, taking place "Out there where the borders of conscience break down, where there is no convention...." It's my favorite of Austin's books.

The shortness of the story is typical for Austin. In fact, she published a collection late in life called "One-Smoke Stories," short-shorts meant to be read in the time it took to have one smoke. (It's just been reissued by Ohio State University Press.)

The line "he had eaten his sorrow and that was the end of it--as it is with men" is echoed in an important letter Mary Austin wrote to her friend and editor Charles Lummis, years later, when Ruth had died (Lummis's little son Amado had died in 1900, and the children knew each other). She explained that Lummis would understand her pain, unlike most people, because "you, like me, have eaten the bread of sorrow on which the gods feed those they specially endow." (Letter dated 28 December 1918, Huntington Library)

The ghost's profile here is interesting--not a person-like vision like in Wharton's story, but a presence, a light, a wind, a smell--unmistakeable, and insistent, but still mute. It changes, somehow, to communicate its receptive or unimpressed response to what Sim or the unnamed neighbor woman says. And it's not scary. Compare it to the way the Maire perceived the invisible ghosts in the opening of The Beleaguered City --the neighbor and Sim might as well be talking about a mouse infestation, the way the accept Emma's return to the house, and discuss how to remove her.

Okay, that's a start. It should be emphasized that the man's confession isn't initially enough to persuade Emma's presence to leave; only when her female neighbor-friend convinces her that Sim isn't going to be able to keep giving such satisfaction, because he's a man, does the ghost depart.

Penny R

Date: Sat, 13 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] More on "The Readjustment"

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

In some editions of the story, the married couple's surname is "Jossylin," not "Jeffries." I suspect the former is the magazine version, the latter the Lost Borders anthology version. There may be other differences, so just a heads up there. (here's a version with the Jossylin surname:

http://www.blackmask.com/books75c/readma.htm )

Penny R

Subject: [Womenwriters] More on "The Readjustment"

Thanks for all the biographical information on Austin. It does cause one to think rather more seriously about the story.

I'm not sure I've previously read a story where the spirit had this nature. I have read of some benevolent ghosts before, but this one wasn't that one either.

I think the spirit got some kind of closure from the husband's declarations, forced though they were.

It was odd to me how matter-of-fact the neighbor took the spirit's presence. It makes me think she had come across this return of the departed before.

Dagny

Date: Sun, 14 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin, "The Readjustment"

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

On Sunday, December 14, 2003, at 07:36 AM, Dagny wrote:

It was odd to me how matter-of-fact the neighbor took the spirit's presence. It makes me think she had come across this return of the departed before.

Austin believed she had contact with the spirits--not in a spooky seancy spiritualist sense, but more as a Native American-derived idea that she was "specially endowed" and attuned to the spirit beings around her. No incantations required (though she loved the ritual drama of chanting and smoking and drums and dancing), you either know their presence or you don't. In several stories, there are dead-come-back, and none of them are greeted with any kind of terror--annoyance, in some places ("The Woman Who Was Never Satisfied" is about a nagging wife who returns to haunt her briefly relieved husband because she's truly never satisfied--even with death). There's a sense of sad longing in others ("The Woman at Eighteen-Mile" is about a woman who sees her married lover one last time, quiet, troubled, in moonlight and shadow, and learns later that he was dead before that encounter).

So the dead-come-back, in Mary Austin's stories, are just stubborn, and return to their partners, to finish business, without malevolence--and their mission is understood in that way, generally, by the living. I don't know enough about the Paiute legends Austin studied and collected and incorporated into her work, but it wouldn't surprise me if there were many such tales in their folk tradition. (There's a good book of Chumash legends, edited by Thomas Blackburn, that I've mined a bit for stories of disability--the Chumash had a simpleton character named Ciqneqs who recurs throughout the book--Austin would also have known some inland Chumash, the Owens Valley towns where she lived were frequented by members of several Native American groups, and near settlements of several such groups.)

Penny R

Date: Sun, 14 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin's Picture

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

I'm trying to catch up and have just looked at the picture of Mary Austin. She has a sombre look; her eyes are intense and sad. I'm also struck by how modern she looks. Compare her apparently outfit, hair, and hat, the way she holds her head in comparison to Edith Wharton. The pictures were taken not that far off in time. Wharton looks like a 19th century woman, Austin our contemporary.

Ellen

Date: Sun, 14 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin (1868-1934)

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Penny's commentary on the story's connection to Austin's life interested me and I went over to the Gale Literary Database (once again) and read the following:

Personal Information:

Family: Born September 9, 1868, in Carlinville, IL; died August 13, 1934, in Santa Fe, NM; daughter of George (a lawyer) and Susanna Savilla (Graham) Hunter; married Stafford Wallace Austin (a sometime agriculturalist), 1891 (divorced, 1914); children: Ruth. Education: Blackburn College, B.S., 1888; University of New Mexico, D.Litt., 1933. Religion: Belief in God as "the experienceable quality in the universe." Hobbies and other interests: Geology, Native American cultures, travel, ecology.

Career:

American nature writer, playwright, and novelist, 1903-34. Also worked as a teacher; lived in artists' communities in New York and London, c. 1905-11; worked for social reforms for women and was involved in Native American rights movement.

Sidelights:

"Mary Austin's most enduring legacy is to be found in her works on the American Southwest, best represented by her first published book, The Land of Little Rain, an extended essay that originally appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. In it, she broke free of a longstanding tradition of romanticizing the subject of the land, writing with a close eye for the telling detail and evoking the grandeur of her subject without lapsing into maudlin sentimentality. Literary editor and professor Carl Van Doren commented in Many Minds on Austin's first achievement, stating, "She speaks as if she had just come back from the desert with fresh truth. But the desert from which she has come is not in California; it is the clear country of the mind."Austin's love of the land is reflected clearly in this first book and in her essays, notably The Flock (1906), which one New York Times reviewer claimed "rejoices chiefly in the open--the free earth, the sun, and the wind," and California: The Land of the Sun (1914). A writer from Athenaeum, in a review of California, maintained, "Mrs. Mary Austin undoubtedly succeeds in giving a picturesque impression of California in its many aspects of beauty and wonder." Austin's affinity for the land also shines through in her novels and short stories, from Outland--in which, a New York Times reviewer lauded, "never has [Austin] given us writing of a more translucent charm or more nearly approaching perfection in phrase and construction," to Lost Borders (1909). Another reviewer in the New York Times praised Austin, saying, "This woman has the eye to see, the heart to understand, the art of words to convey."

Austin came by her love of nature early in life, having discovered a passion for geology at the age of twelve. The love of science and nature never left her, and when she went off to college, she combined a study of art with formal training in science as well. But it was not until she graduated from college and, at age twenty, set out with her mother and brother to homestead in California, that she discovered the land that would call out to her sensibilities most strongly. Within a year she had written her first essay, "One Hundred Miles on Horse Back," and sent it off for publication in her college magazine, The Blackburnian.

As she grew to know this new region, Austin also came to learn more about its inhabitants--the native peoples and the early white settlers. She learned of occasional violent tensions over scarce resources that could erupt into open conflict, particularly as they were played out over irrigation rights in the drought-ridden territory. Austin's own personality also had a major impact on the form that her work--both fiction and nonfiction--would take. Hers was a creative and independent mind, unwilling to conform to the roles normally offered to a young woman of her day. This independent spirit is perhaps what permitted her to look so closely and unromantically at the human relationships that appear in her works. So too did her personal experiences. James P. O'Grady states in American Nature Writers, "it behooves all readers of Austin's work to make the sympathetic leap in regard to her mysticism, so that one might, if not understand, at least appreciate the remarkable gesture she has made again and again, from her first writings to Earth Horizon, in which she reports on the America she saw emerging."

Austin married, at the age of twenty-two, Stafford Wallace Austin, a young man of some apparent charm but few practical abilities and wholly incapable of supporting his new bride. A year later, Austin discovered herself pregnant. When her daughter, Ruth, was born mentally handicapped, Austin turned to her writing to support the family, but soon had to augment the family income by taking teaching positions. When The Land of Little Rain was brought out by Houghton Mifflin in 1903, its reception was immediate and overwhelmingly positive.

In short order, Austin, now writing under her married name, followed up that first book with several others drawn from the same source material--the land of the Southwest, and the people who lived there. Her success allowed her the freedom to focus even more fully on her writing. In 1905, she committed her daughter to an institution dedicated to the care of the mentally retarded, and in 1906, she built a new home in Carmel, California, where a lively artists' colony had been established. She made that move alone, however--her marriage was effectively over although the divorce was not finalized until 1914. Soon after the move, she was diagnosed with breast cancer and, believing that she had but a few months to live, Austin decided to travel to Rome, a city she had long wanted to visit. During her travels, her symptoms disappeared--an occurrence she described as miraculous and one that inspired her to write a number of theologically and philosophically themed works. It also, along with her experiences in marriage and motherhood, led her to take ever more radically feminist positions in her writing. One essay that came out of this period, "The Failure of Free Love," published in Harpers Weekly in 1914, directly attacked the value of marriage and the traditional home.

However, the evolution of Austin's interests, and her work, was not yet complete. In 1917, she undertook a study of the Native American and Hispanic cultures of the Southwest, traveling through New Mexico to conduct her research. Her work from this period is strongly influenced by the cultural preservationist concerns that characterized the anthropology of the time--attempting to recover in her prose many of the arts and folkways that seemed threatened with extinction as white culture grew ever more pervasive throughout the region. For the next two decades, this theme would increasingly come to dominate her writings and her politics. By the time of her autobiography, Earth Horizon (1932), she was prepared to draw upon all her life's influences, rendering them in a powerful, if deeply eccentric, book. A reviewer from Theatre Arts Monthly described this last book as "A beautiful, clear, noble, illuminating portrait of a life that has measured almost the full range of of American living, in place . . . in culture, in religion, in human relationships." Austin died two years after its publication, in 1934, in Sante Fe, New Mexico."

I hope people find the above of interest.

Ellen

Re: Mary Austin's "The Readjustment"

After reading Penny's posting and those of others, and the Gale information, I went back and reread the story. There is more there than appears at first -- and some of it is brought out by knowing about Austin's life.

As I understand it now, Austin blamed herself and then her husband for having a disabled child. She took it either as a sign something was wrong or "incompetent about her husband or something in him deserved punishment. Penny writes:

"Mary blamed Wallace for the rest of her life for their daughter's disability -- she believed he was hiding something about his family history, a "tainted inheritance" that she would never have perpetuated, had she known. When Sim finally sees the Jeffries' child as "the advertisement of his incompetence," he's admitting something Wallace Austin probably never did, but something Mary Austin firmly believed."

I wonder how far she blamed herself too. People don't write down all they fear and are ashamed about themselves. Quite by chance I had my class read Swift's _Last Orders_ where (as in his Waterlands), there is a severely disabled child (she seems to be in a language coma) which throws a permanent wrench into the marriage of the child's parents. The father wants to institutionalize June (the girl's name) and the mother wants to bring her up doing all for her at home. It was a "shot-gun wedding" in the first place; Jack never quite accepted the burden he found put on him; Amy had more than the refusal of Jack to accept their child to hold against him. In class a couple of the young men said Jack was ashamed because to have a "normal" child is a sign of one's masculinity; if you don't have a child, you have (apparently) not done your duty. I hadn't thought of this though I know that I used to wonder if I were to blame for Isabel having been born with a deformed hand. Did I eat or drink something that caused it? Much cruelty is imposed on women in the form of endless advertisements when they are pregnant, warning them against this and urging them to eat that, much with the only half-veiled message that if something goes wrong it's her fault. This should drive her out there to buy this product or eschew that.

So at the heart of two of Swift's fictions is a story of a disabled child. In the second I believe (not sure) the child leads to or commits a justified but nonetheless punishable murder. In both the disabled child is felt as an intolerable burden who far from grateful, endlessly seems to ask more and get in the way emotionally and socially. George Eliot's Cousin Jacob presents a disabled person who ruins the chances of a not-too-well-off family dependent on respectability to claim niches

The woman's ghost may not be malevolent in this story but it is oppressive, frustrated and by obvious inference angry.

The lack of understanding and sympathy displayed by Mary's neighbors is nothing new :). Alas, it's still with us.

Ellen

To WW

Re: The Two Emmas: the ghost as the woman author

One reason I didn't see Emma Saxon as befriending and attempting to protect Mrs Brympton is that in most ghost stories I've read thus far the ghost has been malevolent or mischievous; someone wronged and not returned. I was thinking the interpretation of Emma Saxon as benevolent would preclude another way of looking at these ghosts which might make Lundie (or others of us) uncomfortable: by making oneself into the ghost the woman author punishes herself. She lives up -- or if you will "down" -- to everyone's opinion of her. In "The Readjustment" Mary Austin kills herself in Emma Jossylin and presents her husband as at long last relieved of her.

This is a classic masochistic act: you call attention to yourself through exemplary punishment and assuage your feelings by rage committed on the self. Victoria Glendinning argues that two of Trollope's later novels reveal his own guilt and conflicts because he left no money to a niece, and everything to his two sons; well although she is not malevolent and means very well (frets, worries, is anxious), the ghost in Oliphant's "Old Lady Mary" is driven to try to make contact with a living niece since not only did Lady Mary treat this niece coldly while Lady Mary lived, Lady Mary never told her niece of a will she had made leaving her niece with money. Until Oliphant's two sons died, she did not act that loving and giving to her nieces. So she is punishing herself through Lady Mary, acting out her own terror lest death get irretrievably in the way.

Ellen

Date: Sun, 14 Dec 2003

Subject: Re: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin's "The Readjustment"

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

On Sunday, December 14, 2003, at 08:36 PM, Ellen Moody wrote:

As I understand it now, Austin blamed herself and then her husband for having a disabled child. ... I wonder how far she blamed herself too.

This is pretty much the central matter of my paper recently published as a book chapter ("Bad Blood and Lost Borders: Eugenic Ambivalence in Mary Austin's Short Fiction"--I've already posted the full cite; it's not available online, at least that I know about). It's complicated, of course. A lot of my answer, as my title suggests, is wrapped up in Austin's upbringing, steeped in eugenics through her parents' involvement with the temperance movement (father was a Good Templar, mother was very active in the WCTU after she was widowed, and the WCTU literature in particular blamed drinking dads for the troubles visited on their wives and children, even in the songs it taught through its "Band of Hope" children's programs). Her college major in the 1880s was biology.

On the other hand: Mary lost her mother's sympathy, when she left the Methodist church and embraced edgy causes publicly. Susanna Hunter's response when she learned of Ruth's disability? Blaming Mary in a note that said "I don't know what you've done, daughter, to have such a curse upon you." Susanna Hunter and Mary Austin never spoke again.

Austin wasn't the kind of person to blame herself for much. But she did once write that she was worried that she had thought too hard while she was pregnant, somehow affecting Ruth's prenatal development (maternal impressions is a hardy folk theory). But she was told, by comforting doctors early in Ruth's life, that the disability was not her fault, and she believed them (who knows what they believed--but one of them, Helen Doyle, wrote a very sympathetic biography of Austin after her death). Austin's autobiography, Earth Horizon, spends the first 40 pages or so recounting her family history for several generations before her birth--clearly part of the intent here was to demonstrate her "good stock" and absolve herself further.

As you've probably figured out, "ambivalence" is the best word I can find to describe this facet of Austin's life. She would write one thing in her essays, and another in her fiction. She would say one thing in a letter, and another in her autobiography. I suppose that's true of most folks, about many difficult issues in their lives. I usually conclude for myself that Mary Austin just landed in a really bad time (1892-1918) and a really bad family in which to have a disabled daughter.

Penny R

Re: Mary Austin's "The Readjustment"

The blaming motif in human life is rampant. The problem is people often see patterns where there are none; they tend to remember striking incidents and then bring them together. Atwul Gawande has a fine essay called "The Cancer-Cluster Myth" where he shows how when something bad happens in a given neighborhood -- a couple of people get cancer, it doesn't take much to look about and discern "something wrong" -- by which is meant "something fixable" and behind that the notion that death or bad things shouldn't be. Statistics show that some areas will have more cancers than others, and that is all that is needed for such myths to arise and useless money spent.

Embyronic development and childbirth are so complicated and not well understood that just about any story will do either to blame or to exonerate a malformed child. We don't get excited when we see malformation in other animals or vegetation, only ourselves. I remember when I finally got to a reasoning hand-specialist (surgeon) for Isabel's hand he told me a very pat story which was to prove that it hadn't been my fault. It was very neat, complete with statistics. I remember smiling as he told it thinking to myself so he's a kind man too, decent. (Kaiser first sent us to someone they pay so much a year to do operations; I forget why I walked out but I did; then we were sent to a cosmetic surgeon who had hideous pictures of cosmetic surgeries in a book that reminded me of a wedding book on the table of his office; he took one look at Isabel's hand and went for a camera, offhandedly using the word "freak" for it. He never got to take that picture because we were out of that office before he finished the sentence. There were a couple of others; finally we ended up with the above man, an aging doctor from Lithuania originally, Jewish, a refugee originally; he drew her hand several times.) Careless dumb talk by medical people in hospitals and various impositions (demands the patient/mother attend this "learning" session or that) often does much harm too.

The impulse to blame is not simply innocent or derived from a desire to believe in control and benevolent patterning as inherent in nature (instead of sheer chance and what Stephen Gould shows to be contraptions evolved over eons, many of which are dead ends -- the creature becomes extinct -- or dangerous -- as in childbirth for humans and horses). It also contains in it the desire of others around you to get back and to shield themselves as from a "contagion." (The useful example in understanding scapegoating and destruction of the ill, whether mental or physical, is the chimpanzee with whom we share more than 98% DNA. Chimps will turn on a sick chimp in their group or hound it from the group.) So the person or in the case at hand woman will find herself getting comments which reinforce emotional/atavistic thinking in her own brain, comments which are hard to forget at times. I'm going to do a book with my students this coming term which comes out of DNA studies (Olson, Steven. Mapping Human History: Genes, Race and Our Common Origins. New York: Hougton Mifflin, 2002. ISBN: 0-618-35210-4) which not only shows our way of defining races has no basis in physical realities (we select out for attention physical characteristics which are not salient or important in the gene structure; in fact statistically a "white" person will probably have more in common with any chance "black" person in terms of genes than another "white" person), but puts paid to notions of stock beyond grandparents. People who study their family geneaology past great-grandparents are studying imaginary fancies which are self-flattering nonsense.

So good for Mary that she never spoke to Susanna again. Susanna deserved it. And she was protecting herself from further harassment. I'm sorry to hear about the 40 pages but then they helped her to find some form of release.

It will be obvious that I really don't think that Mary Austin landed in particularly bad family or bad time. Indeed they sound like the norm, the mediocre whose walls (as Mary MacCarthy) says you will burst your braincase on if you try to get inside. They are too thick.

What to do with a disabled child also is an occasion for much harmful talk, blaming and finding reasons for further guilt. A couple of my students over Last Orders pontificated over Jack having put June in an asylum. What a bad man. I suggested that maybe Amy, the wife, was getting back at Jack by going to the asylum for 50 years with never a sign from June -- getting back for all sorts of reasons, pointing out that at Jack's death Amy suddenly thought she had gone to visit June enough. This idea shocked a couple of them and was firmly rejected at first. Myself I've seen this pattern when someone died: the other person had been doing stuff that she didn't care for all that much but irritated the partner where he lived; he's dead and she stops. A couple other students said of Amy, well, what could she have done and she couldn't possibly take care of June, and how dumb she was. It is to be remembered I have only suggested a small group of my students in these conversations; a larger silent group included some who saw more intelligently and were capable of genuine empathy.

Ellen

Date: Mon, 15 Dec 2003

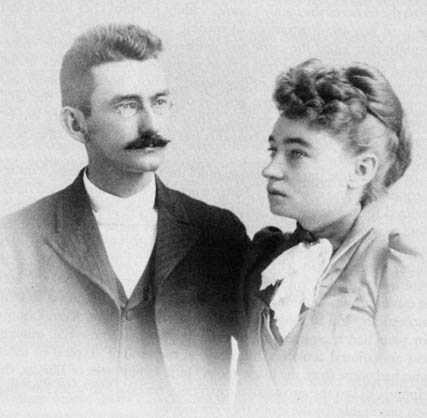

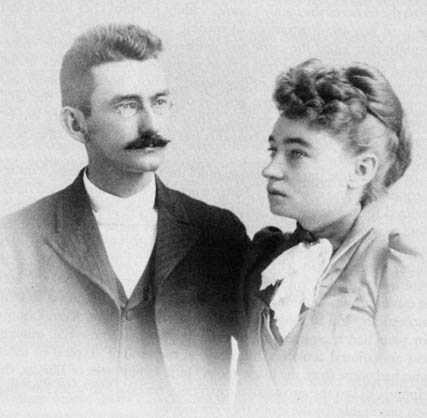

Subject: [Womenwriters] New picture on homepage: Mary Austin and Stafford Wallace

Austin

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

They are not making eye contact, are they? They look past one another. I suppose it's not a good sign when you can't even get yourself to pretend for a photo.

In this picture Mary Austin is much thinner than the other. Her face is smooth, without lines, her hair done up in something of style we saw Edith Wharton use. Is she much younger? She is here a 19th century woman in hairstyle, outfit and photographic presence.

Her husband looks intensely out at the world through his eyeglasses. It may be a factor of the eyeglasses (stereotypical associations) and the intensity of the gaze, but from the picture I am led to imagine him as perceptive, educated. Were they temperamentally uncongenial?

Wallace seems to me a very American name; I've come across it mostly among Americans and in the later 19th and early 20th century. It has an old-fashioned ring and is today mostly turned into Wally.

Ellen

Date: Mon, 15 Dec 2003

Subject: Re: [Womenwriters] New picture on homepage ...

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

I hope this goes through--I've sent off two other messages to the list today that haven't yet (mailed them at noon, grr). I'll answer the questions Ellen raises...

I think that photo was taken soon after their wedding in 1891--so she's only about 10 years younger than the other photo (the hat photo). Mary Austin was a skinny, sickly young woman when she first came to California in 1888, and didn't much improve during her marriage--frequent long separations between the couple were easily explained by her apparent "need" for medical care in a large city.

Austin's hair was never cut (except in front, to make those poofy bangs like in this photo). She complained in an interview, later in life, that all the modern women with bobbed hair were making milliners size down their products, and that she could no longer find hats to fit over her piles of hair. And she commented that women who fussed too much about their hair were immature. She did seem to enjoy letting all her hair down for exotic effect.

Stafford Wallace Austin (always called Wallace) was raised on a plantation in Hawaii, grandson of American missionaries there. He was well-educated, and mild-mannered, a botanist by interest (there's a desert plant named for him). Mary admitted that while she wasn't remotely in love when they married, she hoped he'd be someone she could enjoy as a partner (and she really wanted to get away from dependence on her mother and brothers). She soon learned that, as his plantation upbringing might have suggested, he had little sense of managing money, or working hard, and she spent the first years of her marriage paying off his debts. They remained friendly for decades after their split--he wrote her chatty letters and sent her gifts from his travels, and when he died, Mary's doctor brother signed his death certificate.

I think Mary wanted someone with more passion, more warmth. Someone to argue with--I mean that in a productive sense, someone who would engage, challenge, and appreciate her mind, provide intellectual company. Their neighbors in the Owens Valley felt sorry for him, and told her that she should be grateful for "the extraordinary liberality of her husband's mind" that he let her teach as a married woman.

Penny R

In response Penny, It sounds like what was wrong was they were really not in love. Sometimes I wonder how many people really believe this emotion has any importance. The description you offer shows him to have flaws but not insurmontable ones for her; he also was not someone without learning (which would be very important for her and is not that common an acquirement today and would have been less so then). He was willing to compromise -- even if the way others put this at the time is irritating. But one's inner life is important -- at least it was to this gifted woman.

It's too soon to tell, but I'd like to say I have read a couple more stories from Restless Spirits, among them the one by Dunbar and I'm wondering if the agenda of feminism skewed the choices too far away from attention to high quality. The Dunbar story is susceptible of criticism which could call it silly. It's overdone and the morality at the end is absurd. I understand that women's stories have been left out, omitted; that in most anthologies they have not provided 50% of the stories or anything near that. So Lundie redresses the balance. I also understand that by choosing feminist stories we can see more: for example, that the ghost is a surrogate of the woman author.

Still I'm wondering if the stories would be more stimulating and thrilling -- or unnerving (those are the best) if the more developed richer story had been chosen even if not feminist. Length seems to have been a consideration too. A Beleaguered City is long. It is reprinted with a long ghost story by Francis Hodgson Burnett in my old anthology, The White People. I've never read The White People. I'll see if I have time just as "a control." This is just a thought. Maybe next Xmas (if we're all still here) we can try Dalby's selection or modern ghost stories which are novella length.

Cheers to all,

Ellen

Re: "The Readjustment"

It will be obvious that I really don't think that Mary Austin landed in particularly bad family or bad time. Indeed they sound like the norm...

Hmm. She had Ruth in the thick of the eugenics era--mothers both before (early 1800s) and after that (late 20th) got a lot more sympathy and help from the popular culture, their families, and the community in general. This I've also written about, some, in a forthcoming chapter called "'Beside her Sat her Idiot Child': Families and Developmental Disability in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America" (in a historical reader on developmental disability in America, a mix of primary sources and interpretive essays, due out from NYU Press next year).

And to get back to the story at hand, Mary KNEW that there were better families out there, even at the time. She gave Emma a sister who could take the child away. She gave Emma a husband who would pay for the child's upkeep ("I am sending fifty dollars a month, he can go with the best of them"). Across her stories, where a character with disabilities is included, he or she is often given a kinder, less harsh family and community than Mary herself knew. (Best examples are among her earliest stories, "The Castro Baby," 1899; "The White Hour," 1903; "Pahawitz-Na'an," 1903) In part, her aim was to show how much different the culture of rural California was, and in which ways it might be an improvement over the social habits of her Eastern magazine readers. But in part, this recurring theme seems more personal too--an experiment, like the scientist she wanted to be--the disabled characters in such stories die young anyway; even the best of imaginable circumstances can't keep them from succumbing to an underlying constitutional weakness. After writing a flurry of these stories in the earliest 1900s, I sense that she gave up: she couldn't write her way to a believable good outcome for Ruth.

This is what I find so useful about short stories, as a historian interested in the author's life--if someone has written a lot of them in a short time, on recurring themes, it's a dense record of their imaginings, their interests, what changes or remains unchanged -- like consecutive frames from a filmstrip.

Penny R

Date: Fri, 19 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] 'The Readjustment'

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Hi everyone,

I hope Fran soon recovers from the flu and bronchitis. Sorry not to have been around much the last few days, but I'm having a hectic time at work due to the fact that I edit newspaper TV pages, and Christmas is the time for a frenzy of extra supplements in this department.

I've enjoyed all the postings about Mary Austin and 'The Readjustment', and would like to thank Penny and Dagny for all the biographical information and the photographs, and Ellen for the details from the ever-wonderful Gale database.

I find it hard to think of much to add about this story. I liked it but found it quite slight, until the discussion here about the autobiographical content made me realise that it runs a bit deeper than I had thought.

Although the husband, Wallace, does admit his failings in the marriage, I found the story left me with the feeling that there were problems on both sides. There is the feeling that Emma was determined to mould him into something he wasn't, and made him unhappy as well as herself.

I find this an extraordinary sentence, which I keep coming back to:

"If she had thought to effect anything with Sim Jossylin against the benumbing spirit of the place, the evasive hopefulness, the large sense of leisure that ungirt the loins, if she still hoped somehow to get away with him to some place for which by her dress, by her manner, she seemed forever and unassailably fit, it was foregone that nothing would come of it."

This seems to sum up the distance between them and the spirit of the palce - I am moved by that phrase "evasive hopefulness".

I also read the following story in Restless Spirits 'The Shell of Sense', by Olivia Howard Dunbar, which is closely linked to 'The Readjustment' in theme, again with the wife returning from the grave to see the husband she has just left. I find this an interesting story because it is told *by* the ghost-wife, and I also find something powerful in the style of writing, but I must agree with Ellen that the ending and the implied morality at this point are ludicrous and sentimental. 'The Readjustment' is much stronger in the way it shows the distance between the couple, which can't be suddenly bridged after death. Emma's real discovery is that she and Sim are just as far apart as ever.

All the best,

Judy

Date: Sat, 20 Dec 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] More by Mary Austin

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

If this week's discussion has stirred any interest in reading more by Austin, there's a lot of her short works (stories, poems, essays) online now. This page is full of links and cites (and another photo of Austin, taken later in life, c. 1930):

http://guweb2.gonzaga.edu/faculty/campbell/enl311/austin.htm

Of those listed, I'd say "The Return of Mr. Wills" and "The Woman at Eighteen-Mile" might be of particular interest to WW readers, as they continue some of the themes we've discussed here (the second is a ghost story, even). "Frustrate" is another autobiographical story that might also be of interest.

Penny R

Works (at the University of Virginia)

E-book and Palm versions of Austin's essays on Native American subjects at the University of Virginia

"The Mother of Felipe." Overland Monthly n.s. 20 (Nov. 1892): 534-538.

"The Wooing of the Señorita." Overland Monthly n.s. 29 (Mar. 1897): 258-263.

"The Conversion of Ah Lew Sing." Overland Monthly n.s. 30 (Oct. 1897): 307-312. (illustrated)

"Inyo,"Overland Monthly, July 1899. (poem)

"The Gods of the Saxon," The Independent 52, 26 April 1900: 996. (poem)

"A Shepherd of the Sierras." Atlantic Monthly 86 (July 1900): 54-58.

"The Pot of Gold." Munsey's Magazine 25 (July 1901): 491-495.

"A Pipe Of Oaten Straw," Cosmopolitan 33 (May 1902):79. (poem)

"Jimville: A Bret Harte Town." Atlantic Monthly 90 (1902): 690-694.

"The Little Coyote." Atlantic Monthly 89 (1902): 249-254.

"The Search for Jean Baptiste," St. Nicholas 30 (September 1903): 1024+. (illustrated)

"The White Hour." Munsey's Magazine 29 (April 1903): 88-92. (translation)

The Land of Little Rain (Boston: Houghton Mifflin,1903) (illustrated HTML from the University of Virginia)

HTML at Berkeley/ Illustrated HTML at the Library of Congress

"The Basket Maker." Atlantic Monthly 91 (1903): 235-238.

"The Little Town of the Grape Vines." Atlantic Monthly 91 (1903): 822-25.

"A Land of Little Rain." Atlantic Monthly 91 (1903): 96-99.

"The Last Antelope." Atlantic Monthly 92 (1903): 24-28.

"Mahala Joe." Atlantic Monthly 94 (1904): 44-53.

"The Hoodoo of the Minnietta." Century Magazine 74 (July 1907): 450-453.

"The Return of Mr. Wills." Century Magazine 74 (1907): 244-247.

"The Walking Woman." Atlantic Monthly 100 (1907): 216-220.

"Spring o' the Year." Century Magazine 75 (April 1908): 923-928.

"The Woman at Eighteen-Mile." Harper's Weekly 53, 25 Sept. 1909: 22-23.

"Agua Dulce." Harper's Weekly 53, 28 Aug. 1909: 22-23.

"Bitterness of Women, "Harper's Weekly 9 October 1909 (illustrated)

"Medicine Song to be Sung in Time of Evil Fortune," McClure's 37 (September 1911): 504.

"Indian Songs," Forum 6 (1911) (translation)

"An Appreciation of H. G. Wells, Novelist," American Magazine 72 (October 1911). (illustrated)

"The Song-Makers" 1911 (no journal title given)

"The Song of the Hills: Being the Song of a Man and a Woman Who Might Have Loved."McClure's 37 (Oct. 1911): 615.

"The Song of the Friend." McClure's 38 (Jan. 1912): 351.(translation)

"Frustrate."Century Magazine 83 (Jan. 1912): 467-471.

"Medicine Songs," Everybody's Magazine, September1914

"Art Influence in the West," Century 89.6 (April 1915) (essay) (illustrated)

Reviews of Mary Austin's Work

"The Realism of Mary Austin" and "A New Definition of Genius" 1912.

Rev. of Mary Austin's A Woman of Genius, Current Literature 53, Dec. 1912 698-9.

Mary Austin. Chronicle and Comment section of the Bookman 35 (Aug. 1912): 586.

"A Woman of Genius" by Mary Austin. Review, 1913.

Lincoln Steffens, review. "Mary Austin" (1911)

Subject: [Womenwriters] More by Mary Austin

Thank you to Penny. Such pages are important. They disseminate works widely as they have never been disseminated before.

The photograph is interesting. She looks more conventional here: not so desperate; I can see this image as beloning to some serious 1930s movie. Though she's still not smiling :).

Ellen

Date: Sat, 03 Jan 2004

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin (?) and Jack London

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

I came across an interesting site full of pictures of Jack London: http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/London/Images/search.cgi? Caption=Jack+London&type=and

It takes ages to load.

One of the pictures is labeled: George Sterling, Mary Austin, Jack London, James Hopper in Carmel. Source: The Bancroft Library FindingAid: California Faces: Selections from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection Call Number: London, Jack Portraits:66

You can go directly to this one at: http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/FindingAids/dynaweb/calher/portrait/figure s/I0013331B.jpg

It looks like it could be the Mary Austin whose story we read.

Dagny

Date: Sat, 3 Jan 2004

Subject: [Womenwriters] Mary Austin (?) and Jack London

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

On Saturday, January 3, 2004, at 02:59 PM, dagny wrote:

One of the pictures is labeled: George Sterling, Mary Austin, Jack London, James Hopper in Carmel. Source: The Bancroft Library.It looks like it could be the Mary Austin whose story we read.

Yes, that's her! She was close to all those men, especially Sterling, and quite a noted character even among the many picturesque characters in Carmel's artists' colony (Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, John Muir, Nora May French, Lincoln Steffens were also in the Carmel orbit). She lived at Carmel immediately after institutionalizing Ruth and leaving Wallace, for about five years, before heading off to see Europe in 1909. She was thus in the San Francisco area for the great earthquake in 1906.

Austin's one of the happier stories among this lot: George Sterling and Jack London both committed suicide. Mary kept in touch with London's widow Charmian for years afterward, by correspondence. Of the men in this picture and the others at Carmel, she wrote, "They were the first men I had known who could get drunk joyously in the presence of women whom they respected."

There's much more about this literary/artistic circle of folk, both famed and forgotten, at

http://www.creative.net/~alang/lit/sterling.sht and probably elsewhere too.

Penny R

George Sterling (1869-1926)

Born in Sag Harbor, Long Island, New York in 1869, George Sterling came from an old and respected family descended from the Puritans. His father wanted him to become a priest, so George at age 17 was sent to a Catholic college in Maryland. Fortunately, his studies included poetry -- and the priesthood's loss was literature's gain.The father sent the wayward son to Oakland, California where the uncle -- Frank C. Havens -- was a leading real estate and insurance agent in the area. Here Sterling obtained an office job -- little more than a sinecure that allowed him to continue reading and writing poetry.

In 1892, Sterling met the dominant literary figure on the west coast, Ambrose Bierce, at Lake Temescal and immediately fell under his spell. Bierce -- to whom Sterling referred as "the Master" -- guided the young poet in his writing as well as in his reading, pointing to the classics as model and inspiration. Bierce also published Sterling's first poems in his "Prattle" column in the San Francisco Examiner.

Sterling also met adventure and science fiction writer Jack London, and his first wife Bess at their rented villa on Lake Merritt, and in time they became best of friends. In 1902 Sterling helped the Londons find a home closer to his own in Piedmont, near Oakland. In his letters London addressed Sterling as "Greek" owing to his aquiline nose and classical profile, and signed them as "Wolf." London was later to depict Sterling as Russ Brissenden in his autobiographical novel Martin Eden (1908) and as Mark Hall in The Valley of the Moon (1913).

The Sterling-London friendship disturbed Bierce. London's socialist leanings were sharply contrary to those of the great cynic, and also Bierce feared political philosophy would distract the young poet from his appointed task. After Bierce left for the east coast in 1896, the contest for Sterling's soul was lost, though "the Master" continued to guide his steps from afar.

In November, 1903 W. E. Wood of San Francisco published The Testimony of the Suns, poems written prior to 1901; it was dedicated to Bierce. On first reading the title poem, Bierce had written to his protégé "you shall be the poet of the skies, the prophet of the suns" -- then proceeded to suggest several revisions!

Also in 1903, Sterling completed what many consider his magnum opus, "A Wine of Wizardry," though it was not to be published for four years. Sterling's wife Carrie (Carolyn Rand) later told journalist and writer Joseph Noel that the poet had experimented with opium during the poem's composition, having obtained it from his brother, a physician. In the meantime Bierce campaigned on its behalf, finally arranging for its publication in his employer William Randolph Hearst's newly acquired magazine, Cosmopolitan, in the September 1907 issue. In an introductory note Bierce proclaimed: "no poem in English of equal length has so bewildering a wealth of imagination. Nor Spenser himself has flung such a profusion of jewels into so small a casket. . . it takes away the breath!" Such hyperbolic praise could not go unchallenged, and a counter-wave of deprecation followed, to which Bierce replied in the December issue with "An Insurrection of the Peasantry" with such further bold claims as "Sterling is a very great poet -- incomparably the greatest that we have on this side of the Atlantic" and "[the poem] has all the imagination of 'Comus' and all the fancy of 'The Faery Queen'." Bierce thought so highly of this defense he included it in his collected works. A. M. Robertson published A Wine of Wizardry and other Poems in 1908.

In 1905 Sterling and his wife moved from Piedmont to the sleepy village of Carmel-by-the-Sea, south of Monterey. Here they built a cottage to escape city life; but other poets, writers, and artists soon followed them. An artist colony developed over which Sterling presided, including Mary Austin, photographer Arnold Genthe (whose portrait of Sterling is pictured above), poet Nora May French, James Hopper, John Hilliard, and others.

Sterling also maintained a room at the Bohemian Club in San Francisco, to whose exclusive fold Bierce had given him entrée. This Club (founded in 1872, it was the first in the U.S.) sponsored summer outings on the Russian River, north of San Francisco, which were called "High Jinks" and were attended by Sterling, London, Stewart Edward White, and many others. Sterling wrote and directed a number of plays for these events, including The Triumph of Bohemia: A Forest Play and Truth; A Grove Play.

In 1911, Sterling took on a protégé of his own, the young Clark Ashton Smith. Smith sent Sterling a few poems and was invited to visit the Sterlings in Carmel. Smith stayed a month before returning to Auburn, but maintained contact through correspondence.

Before Bierce's legendary disappearance in 1913, he bade farewell to his few remaining literary friends, including Sterling. He wrote the poet a harsh and damaging letter, which left Sterling bitter. He described Bierce's criticism of young writers as so merciless it was like "breaking butterflies on a wheel." Nevertheless he continued to revere "the Master," writing several appreciations and an introduction to Bierce's Letters edited by Bertha Clark Pope (1922).

Bierce's biographer Richard O'Connor decries "the piddling inconsequentiality of the balance of his [Sterling's] life, largely spent as the resident 'character' of the Bohemian Club." Of course, this ignores what many believe to be Sterling's finest work, the dramatic poem Lilith (1919, 1926) as well as the gracious support Sterling provided to a number of promising writers such as Smith and Robinson Jeffers. All the same, Sterling engaged in "compulsive" love affairs and Carrie divorced him in 1915. Successes included his unofficial status as San Francisco's Poet Laureate, in which mode he wrote an ode to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915, a number of verses dedicated to San Francisco, and a long ode to Yosemite Park. But a string of tragedies also unfolded. As early as 1907, Nora May French committed suicide in his house in Carmel; in 1916 his best friend Jack London died, evidently by his own hand (this is disputed); and his ex-wife Carrie ended her life with poison on November 17, 1918.

In November 1926, the Bohemian Club held a dinner in honor of the critic H. L. Mencken (another Bierce protégé, from the East Coast). It was Mencken who had once suggested Sterling as the "leading contender" for America's Poet Laureate. Sterling had prepared for the visit but illness confined him to his room. Depressed, he swallowed the vial of cyanide he had carried for some years. He was fifty-seven.

Besides his eleven volumes of poetry and four verse dramas, Sterling wrote a critical work on Robinson Jeffers and a number of short stories. Beat poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti has described Sterling as "a kind of leashed Swinburne" and pointed to the influence of Baudelaire and the Symbolist poets.

San Francisco has preserved a George Sterling Glade in the poet's memory. First landscaped in 1928, its only bench cracked in the 1960s and the original plaque was stolen in the '70s. A new plaque on a column was installed at a ceremony in 1982 attended by the city's literati.

Subject: Mary Austin (?) and Jack London -- and George Sterling

Thanks to Dagny and Penny.

Well here are some lessons about communities :).

Sterling is new to me -- we don't learn half enough about this 1890s to 1920s period in US culture. Much of what is taught sticks to a conventional story about political muckraking.

Bierce is a great writer of gothics. Whenever I've had an anthology which includes his work I assign it.

In the old photo, London looks so full of vivid life. Austin wears a rather low-cut blouse :).

Ellen

The reader will find here earlier conversations information, and postings from other threads which concern Mary Austin:

Subject: [Womenwriters] short stories

Reply-To: WomenwritersandRomance@yahoogroups.com

Ellen wrote,

I do like short stories too. I have learned that it's not that common to like short stories: they are an art form.

I suspect some of my taste for short stories comes from my (clinically confirmed!) very slow reading speed--which made grad school hard, but makes books good entertainment investments. The possibility of reading a whole story in a single bite makes them such a different experience from a novel. Besides the Octavia Butler collection mentioned, I've recently liked Andrea Barrett's Ship Fever collection (many with 19th century settings and/or female lead characters, btw) very much, and I see she has a new one (Servants of the Map is some approximation of the title in my memory) that I'd love to pick up too.

My current research project (ie, the one at the top of the pile on my desk, with the most looming deadline) is about eugenic themes in the short stories of Mary Austin (1868-1934). She was good at the form, but devalued it herself, regretting in the end that her life didn't allow the luxury of writing of a great novel (she wrote several novels, which aren't terrible, but the shorts are better). This project has been so fun, reading dozens of short stories by the same woman, knowing where their concerns fit into her own personal/political life, reading through the genre conventions (she wrote "Western" stories) for the underlying cultural anxieties the plots preserve. You can almost watch her "experiment" with various scenarios of parenthood through her short stories--what if the mother and son get separated and THIS happens? or THIS happens-- all while in her own life arranging to be a noncustodial parent to her own daughter (who was severely disabled and difficult to care for at home, especially in rural 1890s California). I don't think writing a novel would have been nearly as accommodating of Austin's need to write through all the trials and errors she could imagine.

Ellen's right, today you almost have to have an established name to get a short story collection published; but in Austin's day, short stories were her way to become established so that she could write novels. The order has flipped.

It's such a switch to hear a science fiction writer described as "too sophisticated" for a group of serious adult readers! As I wrote in my last message, I know Octavia Butler stories and novels are sometimes assigned to very UNsophisticated teenagers for classroom discussion. Hmm.

Penny

Re: Mary Austin

I've spent the last few years living with a project on author Mary Austin (1868-1934). Her papers are nearby, at the Huntington Library, about 6000 items, from letters and photos to drafts of unpublished short stories, snippets of her hair, a cookbook that still smells of vanilla, letters from her publishers and fans, her scrapbooks full of clippings, etc. I've been through them all (on a month's fulltime fellowship). They're not in chronological order, by any means; the letters are alphabetical by author, then recipient, for example. So the story develops on several tracks simultaneously; what seemed trivial on first glance gains importance later when another trivial bit makes a crucial connection. The stories, even the pulpiest ones, are full of revelation. And in the end, the most painful and secret parts of her life remain only sketched--in this case, like in the case of the Blind Assassin's main character, the woman loses/gives up custody of her only daughter, and it remains a hazy patch no matter how you come at it (Mary Austin wrote an autobiography too, and is pretty frank about a lot in it, but on the daughter she becomes vague, anxious to explain without explaining at all). Some of the women in the reading group here were disturbed not to get Iris's full explanation for that part of the story, after all was said and done; for me, it seemed exactly how such an event would be treated by such a woman, even in her "confessions."

So that's an additional way the structure of Blind Assassin works for me. I love novels with multiple formats sewn together like this--I imagine they must be fun and challenging to compose, too.

Penny

Date: Fri, 07 Jun 2002

Subject: [Womenwriters] Nancy Miller's Subject to Change: Women's

Autobiography

Reply-To: WomenwritersandRomance@yahoogroups.com

Ellen quoted Nancy Miller saying,

To justify an unorthodox life by writing about it is to repeat the unorthodoxy a thousandfold.

Hm. This is interesting to me. Permission to think aloud?

I guess the important word there is "justify." The women I write about lived unorthodox lives, but when they wrote about themselves, they didn't exactly try to "justify" their choices. Mary Austin's very strange autobiography (written mostly in third person, with very little in the way of chronological consistency or even milemarkers) does sometimes sound like it's justifying her life, but other times it sounds more like she's making a case that "it wasn't my fault, other people forced these choices on me." In other cases, she pleads no contest to *appearing* unorthodox, only to explain that her choices were actually based on very traditional models, forgotten by her modern peers--turning the table and claiming extreme orthodoxy, I guess you could say. Either way, the reviewers were mostly very admiring of her frankness and painful self-exposures, and none of her revelations brought much additional scorn (although an ex-sister-in-law did try to stop the book from being sold in California, concerned that its contents would reflect badly on her daughter, Austin's niece).

The timing of one's autobiography is also part of this, I suppose. If one waits late enough in life, or at least until after "settling down," one can write about all sorts of shocking adventures without bringing further unwanted scrutiny or disapproval. Austin's autobio appeared just two years before her death, after most of her causes were resolved. Victoria Woodhull didn't write an autobiography (well, not a published or complete one, anyway), but if she had done so in the 1890s or later, she probably wouldn't have tried to justify her earlier life, only admit her earlier excesses and mistakes from the vantage point of eventually respectable later years (for a while after she moved to England, she tried to deny that she even was the *same* Victoria Woodhull who'd done such notorious things in the US--there was some legal wrangling about that, with the British Library, I think).

Maybe it's also the nature of the unorthodoxy? Lives like Sand's and d'Aguoult's which flouted norms of sexual and maternal behavior, were unorthodox in different ways than Austin's (who had little sex life to speak of, but lived and worked on the margins in other ways), or, say, Carry Nation's (ditto). Maybe sexual unorthodoxy is a special case, not really like other kinds of unorthodoxies (though they're all, often, found in a jumble much of the time, or at least assumed to be so).

Again, I don't know, just thinking aloud. Much of my work is about marginalized mothers and their decisions to "go public" about their experiences--so I'm interested in this question of autobiographical honesty and its consequences.

Penny

Re: Sexual Unorthodoxy in Women's Lives

In response to Penny, Sexual orthodoxy is very much a special or different case. Miller and just about all these theoretical feminists I am reading just now show how much much will be forgiven a woman, but not sexual freedom and never sexual promiscuity. Any sexual "lapses" are held against a woman -- if she has none, in order to blacken her they are made up. A man's are still in most cases not held against him.

On Women'sStudies, a large list whose membership is heavily academic is in the midst of an intense & heated discussion over a group of recent books by so-called "third wave" -- or recent generation -- feminists. The core issue argued over is the frank, indeed unashamedly pornographic memoirs or fragments of memoirs which have recently been published or are being published -- the older or second wave feminists are some of them appalled (and threatened) but many are rather dismayed and argue that such publications are simply new fodder for an old mill. If 95% of the world insists on regarding sexual freedom for a woman as ugly/lurid/vile/unacceptable, and framing women who live freely that way (especially as bad mothers), you only buy into, do not break, a stereotype. Among the books discussed is the best-selling _Janes Sexes it Up_ (note the name Jane) and the French journalist/ critic's Catherine Millet's recent memoir of her life.

Ellen

Date: Tue, 21 Oct 2003

Subject: [Womenwriters] Eva Valesh & Women's Autobiography

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

On Tuesday, October 21, 2003, at 06:20 AM, Ellen Moody wrote:

In her study of women's autobiography Jelinek did mention Mary Austin. I would not have noticed the name particularly before I knew Penny. It's just a single sentence and probably reflects a common consensus (if there is one). It occurs in a paragraph listing and characterizing a group of late 19th century "exotic intellectualized autobiographies" by American women: "Mary Austen [1868- 1934) experiments with point of view by mixing first-, and third-person narrators in her study of her mystical pursuits in Earth Horizon."

That's pretty much the consensus. As I've said, it's a frustrating autobiography to work with, for me. Mary Austin would have loved being called "exotic," though -- it was her lifelong aspiration.

But she also tells of how much untruth and evasion there is in most women's autobiographies. Often this has to do with sex and conflicts between the women's career and her homelife. It's not okay for a woman to (as Valesh did) divorce, move to another city and then put her child in a boarding school.

Recent criticism has highlighted the evasions in Earth Horizon, and goodness knows they frustrate me. But the literary reviews in 1932 considered it searing, brave, brutally honest, about exactly the topics you mention: "sex and conflicts between the woman's career and her homelife." Women readers wrote to tell Austin how amazed they were to see someone in the public eye write about such personal experiences. So maybe some of this criticism is a bit of presentism--what seems painfully confessional in one era can seem euphemistic and circumspect a few generations later. Expectations change, naturally. Austin, like Valesh, divorced, moved to another city, and placed her child in an institution--in her case, a "nervous" hospital, where the girl lived out her days until the 1918 flu epidemic--never, to my knowledge, visited by Austin, in keeping with the recommended practice of the day. (The order for Austin is actually this: leave husband permanently after a series of separations, drop daughter off at hospital on the way to settling in Carmel's artists' colony, finally get around to divorcing estranged husband ten years later.) All of this is recounted in EH, as clearly as Austin could probably manage--at least, she tried to be clear--in researching for the book, she wrote to her ex- to get the details of their days together--he obliged with dates, names, and places in a friendly reply.

Just some more background on one woman's "exotic" and "experimental" autobiography. I'm in the throes of writing an Austin paper right now (due last week, yikes), so she's foremost in my mind.

Penny R

Re: Autobiographers and Solitaries

I'm getting round to reading a few books I've been wanting to read for quite a while. One of these is Colegate's study of hermits, solitaries and recluses: Isabel Colegate's A Pelican in the Wilderness.

What does this have to do with women writers? While it seems to be true that an inclination to solitude is as common (or uncommon) among men as among women, as with women's autobiography there are distinct patterns which lead to the "choice of life" and these differ for men and women. Quite a number of Isabel Colegate's solitaries seem to be these "eccentric" (or exotic) women who are intellectual -- and travellers. Most of her more lengthy studies are of women whose names I've heard in connection with travel writing: Isabelle Eberardt is just one of these. I recommend Colegate's book as intelligent and consoling -- it's a book of much irony. For example, the "average" recluse (but there is no average) ends up dead: murdered. We need the eyes of the neighborhood upon us to be safe; we need connection to want to stay alive. However compelling Robinson Crusoe is a myth. Colegate does not meditate abstractly, nor does she limit her investigation to stereotypical solitaries (people in monasteries, people in caves). Instead she has done an enormous amount of research and followed her subjects's footsteps herself (with her husband -- she has made money writing)

Exotic is an odd word. I was once told that coming from the Bronx, New York City, I was exotic. This happened in Leeds. My friend who was on the same "Program of Study Abroad" (though from Brooklyn College, CUNY, while I was from Queens College, CUNY), told me the same word was used of her.

I'm startled at Mary Austin's ruthlessness. Her determination and some of her choices recall those of Dorothy Sayers. I'm the kind of reader that had I know some truths about her life, I would not have been put off by Harriet Vane so much. I know that "fans" are disturbed by Sayers' real life behavior; in contrast, I'm turned off by lies.

What a fascinating subject Mary Austin must be. I can see her hold :).

Cheers to all, Ellen

And now a later posting and brief thread:

Date: Thu, 9 Sep 2004

Subject: [Womenwriters] September 9: Mary Hunter Austin (1868-1934)

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Today on our homepage: A photo of Mary Hunter Austin, born this date in 1868 in Carlinville IL. I've probably said way, way more about Austin's life already onlist than most folks ever want to know (she's one of my research projects, about whom I've published and presented, here and there). When we read an Austin story during the ghost stories read last holidays, Dagny posted most of the available images of Austin; this one isn't anywhere easy to find online, so I scanned it from the frontispiece of the short story collection Western Trails. This looks to have been taken during her Carmel days; her never-cut hair is displayed in one long braid, intertwined with beads.

Penny R

Date: Fri, 10 Sep 2004

Subject: Re: [Womenwriters] September 9: Mary Hunter Austin (1868-1934)

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

On Friday, September 10, 2004, at 06:39 AM, Ellen Moody wrote:

I'm wondering about Penny's last comment: did Austin never cut her hair? When did she stop cutting it? It must've been very long by the time she was old.

Yes, it was--she complained to a New York society writer that the bobbed styles of the 1920s were making it hard to find hats big enough for her own head (that might explain how she came to the solution of wearing a mantilla on special occasions--less fitted). Austin had a lot of odd habits and attachments. Her long thick hair was one of her only conventionally attractive features as a young woman; she might have hoped the long long long hair would read as more connected to nature, a sign of her wilder, Western allegiances, etc. There's a portrait of her taken for publicity c1931, in connection with the publication of her autobiography (so, late in her life) that shows it all coiling around her head--it probably thinned out with age, but it was still long.

There are long, coiled samples of her hair and her daughter's in the Huntington's Austin collection, under the heading "realia." I've seen them, but it felt like I was touching a mummy, or a shrunken head, and I quickly closed that box.

Penny R