Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Oxford & London Jan '09: Climate, houses & dining, Museums & Music · 15 January 09

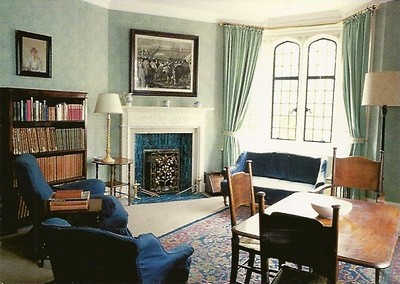

7, St Michael’s Street, Steward’s house, drawing room window, winter’s later afternoon

Dear Friends,

It’s been brutally cold in the DC area for the last couple of days and nights, & we are promised yet more biting, frigid windy air tomorrow. There may be a mild upturn in the thermometer on Sunday so we can have snow. Nevertheless, by 7 am the sky overhead has been filled with faint blushes of pink and yellow, glimmers of light along the bowl’s edge of what one can see of the horizon; by 8 the sky a light blue, and it does not darken until well after 5:15 pm. Twilight’s glow sets in about 5:45. Today most of the afternoon the sky was a bright blue. We are lucky in this house, so many windows, so well situated high on a hill, so much light streams in as we look out on gardens, trees, houses on an ever expanding horizon, depending what angle you look from. Yvette’s room gets the west light of sunset, mine the dawn.

People in the UK are not so lucky, at least in the places and from the angles we dwelt and rode and walked. Jim & I discovered we had forgotten the different kind of cold that penetrates one’s body in January: outside the house, sweaters, woolens, knitted and furred gloves, thick shoes or better yet boots, a heavy-weight jacket, help fend off the damp intense chill, inside double-nightgowns with socks on my feet (how I went to bed), thick sweaters, a gas fire in the center of a room, and hot tea cannot make one thoroughly warm. Everyone wears a scarf.

We had also forgotten how short & dark are the days. At the latitude of Oxford & London, in January sky is only just losing its darkness by 20 to 8 am. Some days the sky was not yet grey by 8 am, and grey shadows shading the light return by 4 pm, & the sky is black by 5 pm.

Nonetheless, after an initial strongly ambivalent reaction to the reality check travel provides, we proceeded to have an increasingly happy, fulfilling and then exhilarating time. Part of this for me came from enjoying the British Society of 18th century studies program, which occurs once a year, most of the time in January. Of this and the separate sessions I’ll write anon. Here I just want to record times with friends, in museums, and music programs we attended and our return home again.

After many hours travel starting at 10 at night US time at Dulles airport on Sunday, we arrived in Oxford late Monday afternoon British time. (The UK is 5 hours ahead of the US.) We had taken the bus from the airport, and first thing we shopped at the covered marketplace and then we made our way to a very old door, loose, and clearly hard to open with a key and knocked and knocked. After an initial panic, the housekeeper appeared at an upper window and let us and our baggage in.

She was a bit unusual for Landmark Trust housekeepers. She really gave us instructions on what was in the place—and thus we learned for the first time how to use the fake coal gas heater. She left us a radio! very wicked I suppose, but we didn’t use it. The steward’s house just behind the Oxford Union where we were staying consisted of two lovely rooms, one for sleeping, and one for a drawing room in front of a fake coal fire; a kitchen, bathroom, hall, stairway to a lower vestibule. It’s a beautifully-appointed elegant place, Edwardian in taste, feel, & objects. The wallpapers were William Morris designs—Morris and Dante Rossetti did famous wall paintings along the walls of the debating room in the Oxford Union across the square. We joined the library for the few days; though we did not take out any books or DVDs, we were able to walk about the place, look at the windows and buildings from the outside. The housekeeper told us (as had the Landmark people in a letter) it was a noisy spot at night because nowadays the Union makes its money as a bar.

We were too tired to explore very much, but did attempt a walk on Tuesday morning before the conference at St. Hugh’s began at noon. Jim came with me that first time to help me find St Hugh’s college, and where I registered. Then he went off, and I remained until around 5 when I returned home by bus and we met Martin, a friend from Trollope-l for dinner.

He took us a roundabout way to a fine cozy French restaurant where we had the best meal I’d had in a long time. On the way as he did a few summers ago, he showed us buildings, and courtyards of some renown or interest (the Bodleian, the first college, an old church, a large square). It was dark and cold, but we could see. A wonderful evening of good conversation and we lured him back to 7, St Michael’s so he could see this restored Edwardian place from the inside. The rooms included a history of the debating center and small contemporary library, including a full set of late 19th and early 20th century bound Punches.

It’s a good thing we had a friend to take us round twice now, for Jim says (rightly I gather) that institutionally speaking Oxford is not a friendly place. The townspeople are courteous and helpful, friendly even, answering all my anxious questions about routes and bus stops, but the Oxford colleges do not sign their buildings at all. Gates everywhere and if you can walk in to a place, you find you are soon told you are walking where you are not allowed to. Virginia Woolf’s experience at Oxford in A Room of One’s Own is not obsolete.

That night was very quiet. The Union bar is in fact closed during the winter recess. The only noise was from a city bar two doors down from ours. Very sad scenes during the day though: across the street from us was a shelter for homeless people to come for food and rest.

The building, next to the shelter seen from the outside

Touching how polite they were to one another, the men helping the women with their shopping carts full of things to get into an old archway which led to the shelter.

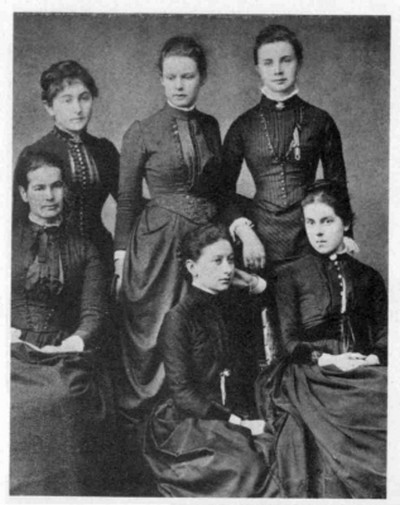

Most of Wednesday Jim rested and in the evening joined me for a musical concert of songs performed by Oxford students and a dinner in the grand dining hall at St. Hugh’s. It was then we learned it was one of the 5 womens’ colleges (see History), all of which have now voluntarily become or been coerced into becoming co-ed. Founded by Elizabeth Wordsworth, and kept up in teeth of no money whatsoever very often, it remained poor and reverted early on. In the rooms there were painted pictures of “old girls” and women professors. Here are the brave first five students who went:

Charlotte Jourdain, Constance Ashburner, Grace Parsons and Jessie Emmerson, joined a term later by Wilhelmina Jane de Lona Mitchell.

The place was not profuse in computers in the manner of US colleges I’ve taught in or Columbia (where Jim went to a reunion a couple of years ago). I very much enjoyed the dining (the food was not bad) since everyone was crowded into long benches and it was therefore easy to make acquaintances and talk, and there was hardly any snobbery.

Thursday was my last conference day and it was a long day’s listening, taking notes, talking and socializing for me. I arrived at St Hugh’s by 9 and stayed until nearly 6. By this time I was an old hand at finding my bus and had made a young friend: a young woman in her 20s with two boys who spent the day with them at their school (they in school, she at work): she and they and I came by the same bus and returned by the same bus. She had that surface cheerfulness and acceptance I’ve seen in so may British people. Jim spent the long day in London: he went to the Oxford club for lunch, walked in the parks, and (as it seemed from the dark rings around his eyes) exhausted himself. So we stayed in. He had bought a good bottle of wine and made for us a pheasant in apple and cream sauce. We sat by our gas fire and after he went to bed, I watched Parts 3 & 4 of the 1999 BBC Aristocrats.

This trip was the first time I had taken a laptop and it helped me get through the night’s later hours when Jim has gone to sleep and I daren’t as I find it hard to sleep more than 5-6 hours (and if I awaken I often have sad tormenting thoughts). Most nights when I grew too tired to read, I watched either Harriet O’Carroll’s Aristocrats (1999, BBC) or David Nokes & Janet Barron’s Clarissa (1991 BBC). I brought Richardon’s Clarissa with me (two heavy volumes), and read it carefully, with intense alertness in the early mornings & became rivetted or absorbed in the way I have done before once I got into the long section of Lovelace and Clarissa’s set-tos from the time she leaves her parents’ house until well after the rape when she finally escapes him to go live in a sponging house under the protection of his decent friend, Belford. Lovelace is (I’ve decided momentarily) a neurotic projection of naive sadistic fantasies on the part of a brilliant repressed and in the pragmatic or concrete real sense sexually inexperienced man.

We said goodbye to our lovely home around 10 am on Friday morning, walked to the train dragging our luggage and were taken to London.

7 Michael’s Street, Steward’s house, again the drawing room, promotional photo by Landmark Trust, perhaps a summer’s afternoon

The transition from one Landmark Trust place to another was fairly painless. All told it took less than 5 hours. The housekeeper let us in early so by 1:30 pm we had put our luggage away and replaced our things in the proper drawers and were on our way to a good supermarket on the other side of the Barbican.

We have stayed in 43 Cloth Fair many times before: it’s a small narrow three floor flat in a block of Georgian buildings in the City of London on a narrow street. Next door to us is perhaps one of the oldest residential buildings in the City: said to be the only remaining house in the City to have survived the great fire in 1666, it was heavily restored by the late Lord Mottistone when he was plain Mr. Paul Paget to house his architectural firm and now, presumably, is owned by a rich family. It has four enormous great doors (big enough for horses to walk through), big square casement windows that jut out and an impressive roof. Our place is known as Betjeman’s house: he was the first Landmark tenant to live there, and (unusually) was a long-term resident. In the usual bookcase filled with well-chosen books appropriate to the area, and place we found a number of books on and by Betjeman.

Drawing room where you can see the fake coal gas fire

There was a rub through: the heat went off at 10 at night and didn’t come back until nearly 7 am, and then went off again about 11:30 am and didn’t come back again until 3. So I warn those who want to stay in London during the winter: you will be very cold in this flat, for while the lovely gas fire provides psychological focus and some warmth, the place is chilly and not comfortable late at night and at midday.

Across the street is a 12th century church, St Bartholomew’s (lovely garden, altar, Roman style); behind that a vast hospital which is ever being fixed (undergoing construction).

St Bartholomew’s and the hospital as seen from the window of Cloth Fair

Along the block are old pubs and cafes. Across the way in the opposite direction are the old meat markets, beyond them along the Strand nowadays clubs, and also (you make a turn to the left at some point or other) Dr Johnson’s house, and carrying on (not that far a walk) you find yourself in one of the theatre and dining districts of London. It is comforting to come back to a place you’ve been numerous times before; it gets to feel like a home away from home (rather like the Williams Club we belong to in NYC).

That night, Friday, we met a new friend I’ve recently made on Austen-l: Arthur Lindley with his wife, Judy. He and I became friendly over some talk about Ian McEwan’s Atonement. He had reserved a place for us at a restaurant called Live Bait. We had loads of fish and drank wine and talked and talked. They are an interesting originally and still American couple who lived for many years in Singapore where he held an academic teaching post in the English department. He began as an 18th century person and did his dissertation on Clarissa (a small world), but gradually moved over to become a medievalist as that was needed. Yes in Singapore. I learned a lot about this place I had never known before. Not hard as I knew practically nothing. He was in London to give a paper on Chaucer’s “Wife of Bath” and then they would return home, home now being Birmingham, where there also reside their 3 cats.

Saturday was the high point of the trip for me. Three good friends came to visit: Clare, who spent many hours to and fro on a train from Torquay, Judy, from Ipswich, and Angela (who I, Jim and our two girls stayed with for 2 weeks a few years ago now) all the way from Ealing! What a day we had together. First in the flat talking (I bought a yummy apple pie, cheese which I forgot to serve, and there was tea), and then we went to the center of London for two exhibits, Annie Lebowitz photographs at the National Portrait Gallery, and next door, at the National Gallery, an exhibit of Sisley paintings done in Britain), a film on the impressionists (where the narrator tried to teach the viewer how to examine a picture and tell if it was really painted out of doors and quickly or inside and from memory markings), and a lovely long lunch at an elegant cafe at the National Gallery.

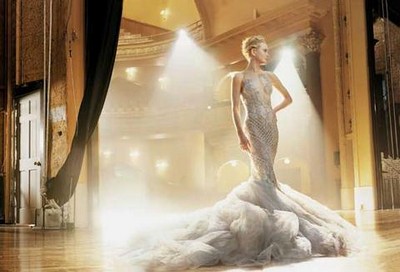

A little on the remarkable Annie Lebowitz exhibit. It intermixed personal, and professional photography, the professional intermixing sheer celebrity photographs which were nonetheless also statements about the nature of celebrity and photographs of famous-numinous people which characterized them revealingly. Here is a typical one of the women stars: Nicole Kidman. We talked of it, and I don’t remember exactly what we said but it was along the lines of what celebrity does to someone. I thought of Marilyn Monroe and her suicide; of how the woman was imprisoned in that outfit, made into an icy object; Judy thought of a mermaid (look down).

Nicole Kidman by Annie Lebowitz

Next to this one were two other of women stars, one young woman part of a rock (?) group as someone to throw darts at. Scarlett Johanssen was among the many portraits of women stars and epitomized the group I thought: she was in an outfit which presented her as sexually available to all comers, very vulnerable. She was trussed up and for sale. Notable was one of Michael Moore looking hard and tough (as he must do) and angry (as he probably is). George W Bush looking cruel, feckless, mean was one of the numerous politicians she caught with her camera.

The personal were some of them family snaps (a child in a baby carriage), many were compassionate, and some few striking. It’s hard to decide the line where work of art begins or ends. A lot of the commentary was about the exhibit as a life-story (Lebowitz had three children in her fifties), but there were as many celebrity& professional photos as personal ones. The ones of Susan Sontag ill and dying did not dominate at all. A great fuss has been made out of these as crossing a boundary to be voyeuristic where one should not be. There were equal photos of Lebowitz’s mother and father grown old, and of him dying.

A happy happy afternoon which ended all too soon. I remember how a group of us from Trollope-l in 1999 visited Salisbury Cathedral (Angela was there, again organizing and negotiating us about) and the two houses now associated with Trollope’s The Warden. Sigmund Eisner said when Jim & I had had to get on a train early to get back to London, the best times are those where we feel we have ended far too early. We talked of books shared, of where we lived, of houses, families, food, the Net, our travels, children.

He told his life story to Mrs Courtly

Who was a widow. ‘Let us get married shortly’,

He said. ‘I am no longer passionate,

But we can have some conversation before it is too late.’

by Stevie Smith

This time I had to get back early to see Rogers and Hammerstein’s Carousel at the Savoy Theatre. Jim had procured half-price tickets and I promised to get back by 6 so we could make the show by 7:30. I admit I enjoyed the music, especially in the first half, melancholy, evasive, especially the rhythmic carousel overture. But as Jim said, the show is made up of pernicious and ugly myths of masculinity and femininity, much of it unreal and meretricious in emotion. Jim thought the one moment of real emotion occurred just after Billy’s death when Julie brokenly repeated the lines from the verses “you’ll never walk alone.” But then (he said) it’s picked up to become a cream sandwich and ruined.

Carousel is a show about two depressives, Billy being a version of Stanley from Streetcar Named Desire and the hero of Rebel Without A Cause, Julie, a self-destructive abject. They are contrasted to absurd caricatures of conventional controlling men (Mr Snow) and prudent women (Carrie) and evil guys who take the young man astray (Jiggers). I noted that the close was not blissful; Billy’s suicide is not compensated for by him being at his daughter’s graduation urging her to “believe,” nor Julie’s wasted life (endlessly crying). The audience sat there, apparently mesmerized, so despite the ludicrous moral teaching close and unreality of the type figures, the piece still touches upon very sore wounds indeed. Like the 1920s opera I saw a couple of summers ago where a girl’s baby dies and the aunt is accused of killing it, this is a musical based on a later Edwardian painful melodrama, this one by Frederic Molnar. The actors and actresses carried it all off with straight faces.

Sunday was our full day alone. We rested in the morning, read (my real comfort book of choice during the time there was again Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake), talked of Betjeman from books and pictures, and had a quiet lunch from the supermarket together. Cheese, tea, the rest of the pie, glasses of wine, and then we headed out for the the Courtauld to see its impressionism and post-impressionism galleries, so deep and satisfying, the famous Manet, Bar at Folies-Bergeres, yet more Pisarros, Monet’s Autumn at Argenteuil:

the fun ice-skating outside (alas I have no photos), and a special exhibit of J.M.W. Turner watercolors, very beautiful. This is not one of those one looks at for beauty, but rather for content: it tells a tale of the 17th century, of a witch spotted by a family. The hare is said to be a sign of a witch:

J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851), Colchester, Essex (1825-26).

A battle was to be fought here. But it is not entirely misogynistic as it seems, for the hare is a familiar animal from poetry of the era, and associated with victims (as in Margaret Cavendish’s famous “The Hunting of the Hare”).

We ate out in an Italian restaurant and in the evening found ourselves at Wigmore Hall.

Wigmore Hall, the foyer

We had never been there before and got tickets for this concert merely because Jim happened by, on the way to the Wallace Collection, and saw the place and the name rang a bell (as they say). Wigmore Hall is a beautiful place, tasteful. First built in 1901 it has been for over a century a venue for classical music, mostly concert performances and works cooperatively with opera houses, and various singing programs, schools, colleges, and symphony halls.

We listened to 2 hours of extraordinarily beautiful music: the singer, Patricia Rozario, on the piano, Julius Drake, and clarinet, Joan Enric Lluna. The first hour was songs by Schubert and Strauss. The second was (not pointed out by the program) not only all modern songs, but all songs of lyrical poems by women, the nineteenth century Galician writer Rosalie de Castro (1837-1885) and two 20th century women poets, Louise de Vilmorin (music byh Francis Poulenc) and Victoria Kamhi de Rodrigo (music by Joaquin Rodrigo).

This is the English translations of a song Rozario just threw her heart into and practically capsized the audience. The music was by Osvaldo Golujov.

Colourless Moon

Moon, colourless

Like the color of pale gold:

You see me here and I wouldn’t like you

To see me from the heights above.

Take me, silently, in your ray

To the space of your journey.

Star of the orphan souls,

Moon, colourless:

I know that you don’t illuminate

Sadness as sad as mine.

Go and tell it to your master

And tell him to take me to his place.

But don’t tell him anything,

Moon, colourless,

Because my fate won’t change

Here or in other worlds.

If you know where Death

Has her dark mansion,

Tell her to take my body and soul together

To a place where I won’t be remembered,

Neither in this world, nor in the heights Above.

One sad note: when the first half was over, a number of people walked out. Why? not because the songs of the second half were by women, or at least they didn’t say that. They were heard to say (and wanted this to be known), they left because they only stay for “classical” music by which they mean 19th century. Anything modern is out. In fact Jim said (and he is the musician not me) Rozario sang much better in the second half because she was so moved by the more particular words with their specific references and appeared to be more at home with modern music too.

Monday morning we had a gap—as we often do on these trips. We had to be out of the apartment by 10 am but the plane would not leave until 3:45 pm. So we left our bags in the hall, and used the time to go to one more treat, what we thought would be a sheer 19th century time.

We walked to the nearby Guildhall and square built by the guilds in the early modern period intending to see an exhibit of G. F. Watt’s work (intelligently done, and I got a real feel for his career and best work), and the 19th century collection at the Guildhall, some unconsciously unfunny but some very good too (including the original of the later Edwardian Garden of Eden which I had put on the Trollope-l groupsite page just before I left).

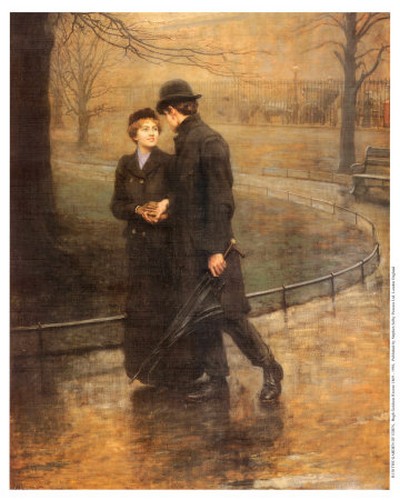

Hugh Golden Rivere (1869-1956), Garden of Eden (undated)

I find it pleasing to look at. It is a sort of image that lies at the heart of 20th century costume dramas, one that flatters people & even I like to think Jim and I have felt. I thought it strikingly different from the story of Emily and Ferdinand Lopez’s marriage in Trollope’s The Prime Minister (on which see below), but alike to that imagined as the public image of Emily and Arthur Fletcher (who this time round I am loving). The autumnal background, the park, a kindly rain against which they are both well-dressed, all is part of the effect. Especially important is the girl’s trusting happy face and her features, and that we don’t see his, only his umbrella, sensible hat, and strong presence.

But we saw much more: an exhibit just ended but not yet taken down about WW1, very powerful by Brian Yale, which rightly showed the terrible destruction for nothing, contrasted it with the fields today in Flanders; the excavation of a Roman amphitheater (so horrific things happened on this site too); modern drawings by students supported by the Guildhall which is itself a handsome building; and not to omit a group of young people who had just graduated with degrees in something they were proud of.

And then it was time to return to 43 Cloth Fair, pick up our bags, and make our way to the airport. On the way to the UK we had been bumped up from World Traveler Plus to Club World so had been able to sleep going. But it’s $700 more to be in “plus” on the way back so we went for steerage. We ate in a British style pub inside the airport as we thought we should have decent food and be comfortable before the long flight back in tight chairs piled together with so many people in a row.

But luckily, we were in a row of three seats by a window. Jim had bought the aisle for him and the window for me. The young man seated in between us was not going to take this (being between a couple offended his pride) and got himself changed to an empty seat in the back. So we had just as much room as if we were in Steerage plus. Thus I finished Aristocrats in comfort, read Shelley’s Frankenstein, Lahiri’s Namesake and ended our trip as I had begun, reading Trollope’s The Prime Minister for hours. Going and coming that’s the novel that held me, kept me going, that I didn’t at all fall asleep on.

Among other mishaps back were 2 extra hours in the air, a busdriver who dawdled over taking his airplane customers and their luggage back to a parking lot a 10 minute trip away (long term relatively inexpensive parking at Dulles Airport) because he wanted to get off earlier (not do another round trip before his time ended), then a dead battery in the car so we had to wait for two angels to show up to jumpstart our battery. The angels arrived in the form of two black men with sophisticated equipment. So we were with Yvette by 8 and before 9 had eaten Chinese food with her and fondled the cats, who showed signs of separation anxiety only the next day. Caroline had been: the signs of this were new toys. We talked and heard how Yvette’s week had gone; she’d been to GMU, a very long ride round by subway. We told her of the bus that stops down the street and goes directly the way I drive along 236.

I’ve left out a lot: like the times we ducked into pubs to join in with the crowds drinking and eating and chatting and keeping warm. One advantage of this climate is people cheer one another as best they can. Like the young woman with her two boys on the bus, they seem to make do splendidly.

And so to bed,

Ellen

P.S. People need to know that the comments you write do “take.”

Barbara at first thought hers hadn’t been registered: “hello Ellen.

Nice to read the account of your recent trip over to the UK. I tried to leave a comment but it doesn’t seem to have taken. here it is in case you prefer to just receive an email.”

What happens is Jim or I have to approve them first. This is the only (crude) way we have of preventing spam from appearing. The blog template does not offer a demand that a real person type out a set of letter s first, so we have to okay whatever is written ourselves. We delete much spam each morning. I know people send me comments as emails, and I am happy to put them on too.

E.M.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Lovely account of your trip, almost like being there. Could almost feel the cold (double nightgowns! gas fires!) and yet coziness, and the St. James Street house looks beautiful. Interesting lectures, good friends, music, Oxford – clearly a most refreshing and stimulating week!

— Diana Jan 16, 8:49am # - Good to hear about the rest of your visit, Ellen – and glad you managed to see and do a lot more on the Sunday and Monday before returning home.

I do think that Edwardian Garden of Eden picture by Hugh Golden Rivere is lovely, and agree with you it has a flavour of costume dramas about it. I also like Turner very much.

It was good to see you again.:)

— Judy Jan 16, 4:14pm # - Ellen

How can I resist making a few comments regarding your recent trip to the UK. So, you didn’t make it up to Leeds? There’s a Landmark here, you know, (Calverley Old Hall) which I am sure would take your fancy!

http://www.landmarker.co.uk/propertydetail?name=Calverley+Old+Hall

I read with interest about your visit to London and Oxford. The latter I long to visit – Christchurch and its art and the Pitt-Rivers and the Ashmolean. I even suggested to my sister that we make a trip and stay at the Steward’s House some time. Unusually for a 2 person Landmark (but like 43 Cloth Fair also) it has twin beds and not a double!

I was staying at 45A Cloth Fair the weekend 2nd-5th January. It’s the larger flat where you’ve stayed when you had family with you. We also shopped at Barbican’s Waitrose but most of our ready meals came from the wonderful Carluccio’s 2 minutes away across West Smithfield. There’s a good Turkish Tas restaurant on Farringdon Road – empty now after the Guardian and Observer have decamped to the Kings Cross area.

We also went to the Guildhall Art Gallery. For us this was the trip after we dropped our bags off at the flat but before we could take over. There are free guided talks on Friday afternoons – partly the main collection – paintings of London and partly the G F Watts exhibit which I found extremely illuminating. But I could not study it all – I was tired after my early start to the day and was ready by 3pm to put my feet up at the flat.

We made visits to the Garden Museum at Lambeth on Saturday and to Kensal Green Cemetery on the Sunday. It was absolutely freezing there but again a most illuminating tour – first to the catacombs and then a tour of the cemetery itself. Anthony Trollope and Wilkie Collins reside there so you have visited already to be sure. We didn’t see them but we saw the final resting place of Harold Pinter and that of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and many other Victorian worthies.

Any time you would like more tips on staying at Cloth Fair – please ask. We’ve stayed every new year for 6 years now. You only had to contact the housekeeper for tips on how to keep the heating going the whole time. This year I asked in advance for the door to be left open where the thermostat etc reside and that did the trick. Just flick the override button. It was horrendously cold this time but I knew in advance we wouldn’t all be out all day and checked that we would be able to do that.

Barbara

— BARBARA HOWARD Jan 16, 4:50pm # - So glad you’ve both discovered the Wigmore Hall. It’s a wonderful building and I’ve spent many happy hours there listening to great music.

Clare

— Clare Shepherd Jan 16, 5:51pm # - Dear Barbara,

Thank you very much for the full comment and advice on how to turn up the heat at Cloth Fair. Also about take-out places nearby. This time we cooked less than we sometimes do. We were there but 3 nights. We have been to Trollope’s grave and also visited one of his houses—with John Letts (very kind of him).

Jim told me about Almshouse another, somewhat smaller Landmark place in Yorkshire. We’ll keep it in mind.

We just missed one another :)

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 17, 12:03am # - From Tom:

“Dear Ellen: It is very well that you and the Admiral have returned safe and sound. From what I’ve read thus far on your blog you had a swell trip. Am I looking in vain for any mention of book stores you visited? Any new acquisitions?!”

— Elinor Jan 18, 7:51am # - Dear Tom,

We did not visit any bookstores except Waterstones to buy Terry Pratchett’s Thud for Isabel. There were book displays at the conference and I bought a couple of books cheaper when I got home, in particular a great biography of Anna Barbauld by William McCarthy. At the museums there were bookshops too (I bought while there the book of reproductions of Turner’s watercolors called Paths to Fame), but as we were carrying a heavy 2-volume Clarissa as well as laptop, two sets of DVDs, about 7 others, not to omit four suitcases, and lately I’ve been trying not to buy just like this—in order try to conserve money a bit and see what we can do for Isabel, we only bought the Pratchett and Turner. Pratchett is not available in US stores or on Amazon.com, only Amazon.uk; and the Turner was but 10 pounds and offered a wealth of lovely reproductions.

I did have quite a splurge when I got home, that is, as I say, beyond McCarthy, I bought some of what I saw at the conference cheaper on the Net (3 fine books on movie adaptations, Gidding’s The Classic Serial and Screening the Novel, The History of Costume Drama by Pam Cook; & an old insightful book, Morris Golden's Richardson's Characters), and came home to new ones which had arrived while I was gone (Chesnil Beach by McEwan, The Book of Not by Dangarembga), and an as yet unread Christmas present (Lahiri's Unaccustomed to Earth), but all are books connected to teaching or projects or reading for listservs (a CD set of Anne Bronte's Agnes Grey unabridged & read aloud by Donada Peters). I stayed away from the superexpensive, the kind of book that goes for over $50 -- for example, The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe is a splendid encyclopedia, chock-a-block with information and insight, huge, but Continuum wants $200!

Admittedly the choices include beloved womens’ novels & memoir, biographies to be getting on with as friends. Lahiri falls into that category and from his talk I’m hoping McCarthy will be so too.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 18, 7:57am # - From Gene on Trollope-l:

“Hi Ellen,

I’m so jealous of your visit to Wigmore Hall. If someone hasn’t told you already, conserves are broadcast over the Internet on BBC from Wigmore Hall Monday through Friday. Enjoy.

Gene”

— Elinor Jan 18, 10:51am # - The same friend on gatekeeping:

“Good Morning Ellen,

Oh – please don’t misunderstand – I did not mean that what you had submitted “was flawed” in any way! My only suggestion was that you choose to focus the wealth of material you had assembled more on one specific subject for this paper/talk and reserve the remainder for other papers/lectures. Really, it sounds as if you have assembled the outline of an entire book here: so the JASNA paper might just be one of its chapters! In other words, you grew the flowers in the garden and picked a luscious sampling; I was just suggesting how you might arrange them in the vase …

That the deciding boards of these meetings all have agendas that often have more to do with pleasing a particular constituency is a shame. But, sadly, that is the way the world works. In literary, academic, as well as political life, so much seems to depend on the “hidden” [or not so] agendas of others.

Best wishes …”

— Elinor Jan 18, 12:08pm # - From Angela:

“I’ve got the Turners at the Courtauld on my ‘to see’ list and I’m very glad you liked the stuff at the Guildhall. It’s such an institutional place, quite unlike a museum but they have a lot of interesting art including a number of William Collins which are too unfashionable to have on display. How great that you went to the Wigmore as well, I so seldom go there …

I’m still thinking about the Annie Lebowitz and its strange juxtapositions, that says something about an exhibition. ”

— Elinor Jan 21, 3:47pm #

commenting closed for this article